https://www.covidexitstrategy.org/

.png)

https://www.covidexitstrategy.org/

.png)

Here are some other significant developments:

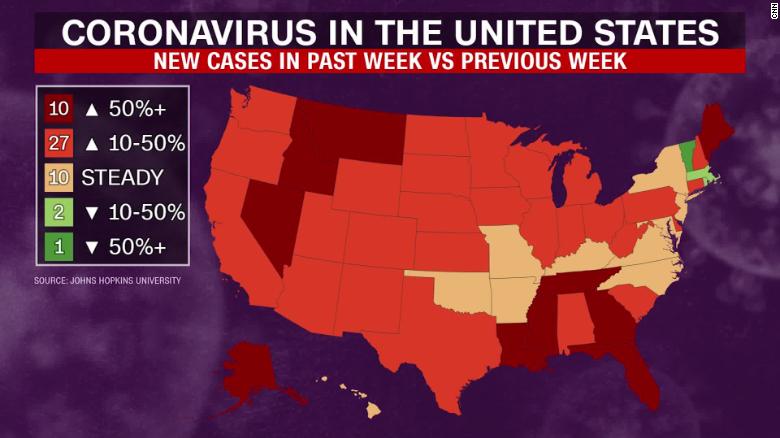

Infections and deaths are rising in states around the country, led by Texas, California, Florida, Georgia and Arizona. Texas on Friday reported a record 14,916 new cases and 174 new deaths related to the virus. Other states, including Ohio, Utah and the Carolinas, have reported single-day records in the past week.

The sharp increases have prompted many states to adopt new public health measures to prevent the virus spread. California ordered most of its schools to conduct remote instruction in the new academic year unless counties can meet strict benchmarks for reducing community transmission. More than half of all U.S. states have instituted some form of statewide mask requirements, including Alabama and Arkansas, where governors previously balked at mask mandates.

https://covidtracking.com/blog/weekly-update-unchecked-new-cases-turn-deadly

The US is approaching half a million new cases of COVID-19 each week. States with major outbreaks including Arizona, California, Florida, and Texas all saw record high weekly hospitalizations and deaths. Meanwhile, worsening outbreaks in many other states threaten to increase the pandemic’s death toll in the coming weeks.

This week, about 435,000 Americans were diagnosed with COVID-19. This is our fourth week of big increases in the number of new cases, and the results of this case surge are becoming clear. As of July 15, more than 56,000 people are currently in the hospital with COVID-19 in the United States. This week, states reported that 4,872 more people have died of COVID-19, an increase of nearly 29 percent from the previous week.

There are no surprises in these new death numbers: people are dying of COVID-19 in the same places where cases have been surging and COVID-19 hospital admissions have spiked. Fourteen states reported more than 100 COVID-19 deaths in the last week, and eight of those states were in the South, the region so far hit hardest in the second surge of cases. Slightly fewer than half the deaths were reported by the four states with the biggest outbreaks—Arizona, California, Florida, and Texas—and most of the rest were distributed down the Eastern Seaboard and across the South.

Our national view of how many people are currently hospitalized with COVID-19 is clearer now that Florida has finally released current hospitalization data. With hospitalizations from Florida’s outbreak accounted for, the national hospitalization figures are approaching their previous peak levels from April of this year.

Hospital data has been in the news for other reasons as well. The US Department of Health and Human Services has directed hospitals to report COVID-19 data directly to HHS, rather than to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. At The COVID Tracking Project, we compile all our data from official state and territorial sources—not from any federal agency. Nevertheless, we have already seen state-level hospital data go dark in at least one state, Idaho, as a result of the new HHS directive. We hope and expect that hospital reporting through many states will continue uninterrupted, and we’ll be reporting what we learn about states’ experience with the new directive.

Outside of the five states with the biggest outbreaks, several other states posted alarming data this week. In several states across the South, case growth is smaller in absolute terms, but the trends we see this week mirror those we saw in Arizona and Florida a few weeks ago. We hope not to see those trends continue and result in the huge case spikes—and subsequent large increases in hospitalizations and deaths—that we saw in the states worst hit in the pandemic’s second surge.

Public health interventions in these states have varied widely this week. In Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, new mask orders and other restrictions have gone into effect. North Carolina has been under a mask order since June 25, and has reported a less explosive rise in new case growth than the other four states we’re watching in this group of southern states. In Georgia, the governor has explicitly voided local mask orders in Georgia cities and counties.

This week, US states and territories reported more than five million COVID-19 tests in a single week—a major achievement amid continuing testing shortages in many areas. For context, the Harvard Global Health Institute estimates that the United States will need to perform at least 8.4 million tests per week to slow the spread of the virus, and 30 million tests per week to suppress the pandemic.

You can learn all about our data compilation process, including an overview of our collection and publication process, our data sourcing policy, and exact definitions of the data points we track here on our website and in our API. To keep up to date on our work, follow us on Twitter and join our low-frequency email list.

Coronavirus deaths are again on the rise in the U.S., with all three of the nation’s largest states setting new highs for daily death tolls Thursday following weeks of record increases in new cases and hospitalizations, even as President Donald Trump and other conservatives have touted death statistics as a sign the U.S. is handling the pandemic well.

California, Texas and Florida all reported new record daily highs for deaths Thursday.

California reported 149 deaths, while Florida reported 120 and Texas set a new record for the third-straight day, with 105.

Deaths are rising rapidly in Texas, with the 105 deaths breaking Wednesday’s record of 98, which shattered the record of 60 that was set on Tuesday.

Coronavirus deaths in the U.S. declined from early May through mid-June, but have picked up recently, and are now pacing at just under 1,000 per day.

The rise is being driven by record new death tolls in the nation’s largest states—the same states that have in large part contributed to the U.S.’s record rise in new cases recently.

Experts have said that deaths lag behind increases in cases and hospitalizations, with former FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb saying in an interview Sunday that “the total number of deaths is going to start going up again.”

Coronavirus deaths reached a peak nationally in April through early May with over 2,000 a day on many days, largely driven by the severe outbreak in New York. Now the pandemic has eased in the Northeast while states in the South and West are the new national epicenters for coronavirus.

Trump and Republican politicians had used the decline in deaths and a decrease in mortality rates to argue that the U.S. response to coronavirus has worked. However, there has also been a massive increase in testing, meaning that many less severe cases are now being identified.

4.3%. According to Johns Hopkins University, that’s what the current mortality rate is among confirmed coronavirus cases in the U.S., a number that’s continually dropped as testing has increased. However, health experts like Dr. Anthony Fauci said early on in the pandemic that they believe the actual mortality rate is around 1%, which is still at least 10 times the lethality of the seasonal flu. And Gottlieb noted that even if the reported death rate continues to drop, if there is an increase in infections, the amount of deaths will ultimately rise, as well.

“It’s a false narrative to take comfort in a lower rate of death,” Fauci said on Tuesday, adding “There’s so many other things that are very dangerous and bad about this virus, don’t get yourself into false complacency.”

As Florida becomes the new epicenter of the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S., the state is trying to ensure that nursing homes and rehabilitation facilities aren’t quickly overwhelmed by patients still suffering from the disease.

So far, it has dedicated 11 facilities solely to COVID patients who need post-acute or long-term care: those who can’t be isolated at their current facilities, as well as those who’ve gotten over the worst of their illness and who can be moved to free up hospital beds for the flow of new patients.

One of those facilities is Miami Medical Center, which was shuttered in October 2017 but now transformed to care for 150 such patients. In total, the network of centers will handle some 750 patients.

“We recognize that that would be something that would be very problematic, to have COVID-positive nursing home residents be put back into a facility where you couldn’t have proper isolation,” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) said during a press briefing last week. “[That] would be a recipe for more spread, obviously more hospitalizations and more fatalities, and so we prohibited discharging COVID-positive patients back into nursing facilities.”

Whether 750 beds will be enough to accommodate the state’s needs remains a question, but it’s a necessary first step, given testing delays that in some cases stretch more than a week. Experts have warned that patients recovering from COVID shouldn’t be transferred to a facility without being tested first.

Without dedicated facilities, hospitals in Florida in dire need of beds for new patients might have had no other choice.

Key Role for Testing

There are no national data on the percentage of hospitalized COVID-19 patients who need rehabilitation or skilled nursing care after their hospital stay.

In general, about 44% of hospitalized patients need post-acute care, according to the American Health Care Association and its affiliate, the National Center for Assisted Living, which represent the post-acute and long-term care industries.

But COVID has “drastically changed hospital discharge patterns depending on local prevalence of COVID-19 and variations in federal and state guidance,” the groups said in an email to MedPage Today. “From a clinical standpoint, patients with COVID-19 symptoms serious enough to require hospitalization may be more likely to require facility or home-based post-acute medical treatment to manage symptoms. They also may need rehabilitation services to restore lost function as they recover post-discharge from the acute-care hospital.”

The level of post-acute care these patients need runs the spectrum from long-term acute care hospitals and inpatient rehabilitation facilities to skilled nursing facilities and home health agencies.

The variation is partly due to the heterogeneity of the disease itself. While some patients recover quickly, others suffer serious consequences such as strokes, cardiac issues, and other neurological sequelae that require extensive rehabilitation. Others simply continue to have respiratory problems long after the virus has cleared. Even those who are eventually discharged home sometimes require home oxygen therapy or breathing treatments that can require the assistance of home health aides.

Yet post-acute care systems say they haven’t been overwhelmed by a flood of COVID patients. Several groups, including AHCA, NCAL, and the American Medical Rehabilitation Providers Association (AMRPA) confirmed to MedPage Today that there’s actually been a downturn in post-acute care services during the pandemic.

That’s due to a decline in elective procedures, the societies said, adding that demand is starting to pick back up and that systems will need to be in place for preventing COVID spread in these facilities.

Testing will play a key role in being able to move patients as the need for post-acute care rises, specialists told MedPage Today.

“You shouldn’t move anyone until you know a status so that the nursing facility can appropriately receive them and care for them,” said Kathleen Unroe, MD, who studies long-term care issues at the Regenstrief Institute and Indiana University in Indianapolis.

AHCA and NCAL said they “do not support state mandates that require nursing homes to admit hospital patients who have not been tested for COVID-19 and to admit patients who have tested positive. This approach will introduce the highly contagious virus into more nursing homes. There will be more hospitalizations for nursing home residents who need ventilator care and ultimately, a higher number of deaths.”

Earlier this week, the groups sent a letter to the National Governors Association about preventing COVID outbreaks in long-term care facilities. They pointed to a survey of their membership showing that, for the majority, it was taking 2 days or longer to get test results back; one-quarter said it took at least 5 days.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently announced that it would send point-of-care COVID tests to “every single” nursing home in the U.S. starting next week. Initially, the tests will be given to 2,000 nursing homes, with tests eventually being shipped to all 15,400 facilities in the country.

Hospitals can conduct their own testing before releasing patients, and this has historically provided results faster than testing sites or clinical offices, especially if they have in-house services. However, demand can create delays, experts said.

Preparing for the Future

Jerry Gurwitz, MD, a geriatrician at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, says now is the time to develop post-acute care strategies for any future surges.

Gurwitz authored a commentary in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society on an incident in Massachusetts early in the pandemic where a nursing home was emptied to create a COVID-only facility, only to have residents test positive after the majority had already been moved.

“We should be thinking, okay, what are the steps, what’s the alternative to emptying out nursing homes? Can we make a convention center, or part of it, amenable to post-acute care patients?” Gurwitz said. “Not just a bed to lie in, but possibly providing rehabilitation and additional services? That could all be thought through right now in a way that would be logical and lead to the best possible outcomes.”

Organizations can take the lead from centers that have lived through a surge, like those in New York City. Rusk Rehabilitation at NYU Langone Health created a dedicated rehabilitation unit for COVID-positive patients.

“We were able to bring patients out from the acute care hospital to our rehabilitation unit and continue their COVID treatment but also give them the rehabilitation they needed” — physical and occupational therapy (PT/OT) — “and the medical oversight that enhanced their recovery and got them out of the hospital quicker and in better shape,” Steven Flanagan, MD, chair of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone, said during an AMRPA teleconference.

Flanagan noted that even COVID patients who can be discharged home will have long-term issues, so preparing a home-based or outpatient rehabilitation program will be essential.

Jasen Gundersen, MD, chief medical officer of CareCentrix, which specializes in post-acute home care, said there’s been more concern from families and patients about going into a facility, leading to increased interest in home-based services.

“We should be doing everything we can to support patients in the home,” Gundersen said. “Many of these patients are elderly and were on a lot of medications before COVID, so we’re trying to manage those along with additive medications like breathing treatments and inhalers.”

Telemedicine has played an increasing role in home care, to protect both patients and home health aides, he added.

Long-term care societies have said that emergency waivers implemented by CMS have been critical for getting COVID patients appropriate levels of post-acute care, and they hope these remain in place as the pandemic continues.

For instance, CMS relaxed the 3-hour therapy rule and the 60% diagnostic rule, Flanagan said. Under those policies, in order to admit a patient to an acute rehabilitation unit, facilities must provide 3 hours of PT/OT every day, 5 days per week.

“Not every COVID patient could tolerate that level of care, but they still needed the benefit of rehabilitation that allowed them to get better quicker and go home faster,” he said.

Additionally, not every COVID patient fits into one of the 13 diagnostic categories that dictate who can be admitted to a rehab facility under the 60% rule, he said, so centers “could take COVID patients who didn’t fit into one of those diagnoses and treat them and get them better.”

AHCA and NCAL said further waivers or policy changes would be helpful, particularly regarding basic medical necessity requirements for coverage within each type of post-acute setting.

But chief among priorities for COVID discharges to post-acute care remains safety, the groups said.

“The solution is for hospital patients to be discharged to nursing homes that can create segregated COVID-19 units and have the vital personal protective equipment needed to keep the staff safe,” they said. “Sending hospitalized patients who are likely harboring the virus to nursing homes that do not have the appropriate units, equipment and staff to accept COVID-19 patients is a recipe for disaster.”

https://www.vox.com/2020/7/14/21324201/covid-19-long-term-effects-symptoms-treatment

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67056715/GettyImages_1224443008.0.jpg)

People with long-term Covid-19 complications are meanwhile struggling to get care.

In late March, when Covid-19 was first surging, Jake Suett, a doctor of anesthesiology and intensive care medicine with the National Health Service in Norfolk, England, had seen plenty of patients with the disease — and intubated a few of them.

Then one day, he started to feel unwell, tired, with a sore throat. He pushed through it, continuing to work for five days until he developed a dry cough and fever. “Eventually, I got to the point where I was gasping for air literally doing nothing, lying on my bed.”

At the hospital, his chest X-rays and oxygen levels were normal — except he was gasping for air. After he was sent home, he continued to experience trouble breathing and developed severe cardiac-type chest pain.

Because of a shortage of Covid-19 tests, Suett wasn’t immediately tested; when he was able to get a test, 24 days after he got sick, it came back negative. PCR tests, which are most commonly used, can only detect acute infections, and because of testing shortages, not everyone has been able to get a test when they need one.

It’s now been 14 weeks since Suett’s presumed infection and he still has symptoms, including trouble concentrating, known as brain fog. (One recent study in Spain found that a majority of 841 hospitalized Covid-19 patients had neurological symptoms, including headaches and seizures.) “I don’t know what my future holds anymore,” Suett says.

Some doctors have dismissed some of his ongoing symptoms. One doctor suggested his intense breathing difficulties might be related to anxiety. “I found that really surprising,” Suett says. “As a doctor, I wanted to tell people, ‘Maybe we’re missing something here.’” He’s concerned not just for himself, but that many Covid-19 survivors with long-term symptoms aren’t being acknowledged or treated.

Suett says that even if the proportion of people who don’t eventually fully recover is small, there’s still a significant population who will need long-term care — and they’re having trouble getting it. “It’s a huge, unreported problem, and it’s crazy no one is shouting this from rooftops.”

In the US, a number of specialized centers are popping up at hospitals to help treat — and study — ongoing Covid-19 symptoms. The most successful draw on existing post-ICU protocols and a wide range of experts, from pulmonologists to psychiatrists. Yet even as care improves, patients are also running into familiar challenges in finding treatment: accessing and being able to pay for it.

Scientists are still learning about the many ways the virus that causes Covid-19 impacts the body — both during initial infection and as symptoms persist.

One of the researchers studying them is Michael Peluso, a clinical fellow in infectious diseases at the University of California San Francisco, who is currently enrolling Covid-19 patients in San Francisco in a two-year study to study the disease’s long-term effects. The goal is to better understand what symptoms people are developing, how long they last, and eventually, the mechanisms that cause them. This could help scientists answer questions like how antibodies and immune cells called T-cells respond to the virus, and how different individuals might have different immune responses, leading to longer or shorter recovery times.

At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, “the assumption was that people would get better, and then it was over,” Peluso says. “But we know from lots of other viral infections that there is almost always a subset of people who experience longer-term consequences.” He explains these can be due to damage to the body during the initial illness, the result of lingering viral infection, or because of complex immunological responses that occur after the initial disease.

“People sick enough to be hospitalized are likely to experience prolonged recovery, but with Covid-19, we’re seeing tremendous variability,” he says. It’s not necessarily just the sickest patients who experience long-term symptoms, but often people who weren’t even initially hospitalized.

That’s why long-term studies of large numbers of Covid-19 patients are so important, Peluso says. Once researchers can find what might be causing long-term symptoms, they can start targeting treatments to help people feel better. “I hope that a few months from now, we’ll have a sense if there is a biological target for managing some of these long-term symptoms.”

Lekshmi Santhosh, a physician lead and founder of the new post-Covid OPTIMAL Clinic at UCSF, says many of her patients are reporting the same kinds of problems. “The majority of patients have either persistent shortness of breath and/or fatigue for weeks to months,” she says.

Additionally, Timothy Henrich, a virologist and viral immunologist at UCSF who is also a principal investigator in the study, says that getting better at managing the initial illness may also help. “More effective acute treatments may also help reduce severity and duration of post-infectious symptoms.”

In the meantime, doctors can already help patients by treating some of their lingering symptoms. But the first step, Peluso explains, is not dismissing them. “It is important that patients know — and that doctors send the message — that they can help manage these symptoms, even if they are incompletely understood,” he says. “It sounds like many people may not be being told that.”

Even though we have a lot to learn about the specific damage Covid-19 can cause, doctors already know quite a bit about recovery from other viruses: namely, how complex and challenging a task long-term recovery from any serious infection can be for many patients.

Generally, it’s common for patients who have been hospitalized, intubated, or ventilated — as is common with severe Covid-19 — to have a long recovery. Being bed-bound can cause muscle weakness, known as deconditioning, which can result in prolonged shortness of breath. After a severe illness, many people also experience anxiety, depression, and PTSD.

A stay in the ICU not uncommonly leads to delirium, a serious mental disorder sometimes resulting in confused thinking, hallucinations, and reduced awareness of surroundings. But Covid-19 has created a “delirium factory,” says Santhosh at UCSF. This is because the illness has meant long hospital stays, interactions only with staff in full PPE, and the absence of family or other visitors.

Theodore Iwashyna, an ICU physician-scientist at the University of Michigan and VA Ann Arbor, is involved with the CAIRO Network, a group of 40 post-intensive care clinics on four continents. In general, after patients are discharged from ICUs, he says, “about half of people have some substantial new disability, and half will never get back to work. Maybe a third of people will have some degree of cognitive impairment. And a third have emotional problems.” And it’s common for them to have difficulty getting care for their ongoing symptoms after being discharged.

In working with Covid-19 patients, says Santhosh, she tells patients, “We believe you … and we are going to work on the mind and body together.”

Yet it’s currently impossible to predict who will have long-lasting symptoms from Covid-19. “People who are older and frailer with more comorbidities are more likely to have longer physical recovery. However, I’ve seen a lot of young people be really, really sick,” Santhosh says. “They will have a long tail of recovery too.”

At the new OPTIMAL Clinic at UCSF, doctors are seeing patients who were hospitalized for Covid-19 at the UCSF health system, as well as taking referrals of other patients with persistent pulmonary symptoms. For ongoing cough and chest tightness, the clinic is providing inhalers, as well as pulmonary rehabilitation, including gradual aerobic exercise with oxygen monitoring. They’re also connecting patients with mental health resources.

“Normalizing those symptoms, as well as plugging people into mental health care, is really critical,” says Santhosh, who is also the physician lead and founder of the clinic. “I want people to know this is real. It’s not ‘in their heads.’”

Neeta Thakur, a pulmonary specialist at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center who has been providing care for Covid-19 patients in the ICU, just opened a similar outpatient clinic for post-Covid care. Thakur has also arranged a multidisciplinary approach, including occupational and physical therapy, as well as expedited referrals to neurology colleagues for rehabilitation for the muscles and nerves that can often be compressed when patients are prone for long periods in the ICU. But she’s most concerned by the cognitive impairments she’s seeing, especially as she’s dealing with a lot of younger patients.

These California centers join new post-Covid-19 clinics in major cities across the country, including Mount Sinai in New York and National Jewish Health Hospital in Denver. As more and more hospitals begin to focus on post-Covid care, Iwashyna suggests patients try to seek treatment where they were hospitalized, if possible, because of the difficulty in transferring sufficient medical records.

Santosh recommends that patients with persistent symptoms call their closest hospital, or nearest academic medical center’s pulmonary division, and ask if they can participate in any clinical trials. Many of the new clinics are enrolling patients in studies to try to better understand the long-term consequences of the disease. Fortunately, treatment associated with research is often free, and sometimes also offers financial incentives to participants.

But otherwise, one of the biggest challenges in post-Covid-19 treatment is — like so much of American health care — being able to pay for it.

Outside of clinical trials, cost can be a barrier to treatment. It can be tricky to get insurance to cover long-term care, Iwashyna notes. After being discharged from an ICU, he says, “Recovery depends on [patients’] social support, and how broke they are afterward.” Many struggle to cover the costs of treatment. “Our patient population is all underinsured,” says Thakur, noting that her hospital works with patients to try to help cover costs.

Lasting health impacts can also affect a person’s ability to go back to work. In Iwashyna’s experience, many patients quickly run through their guaranteed 12 weeks of leave under the Family Medical and Leave Act, which isn’t required to be paid. Eve Leckie, a 39-year-old ICU nurse in New Hampshire, came down with Covid-19 on March 15. Since then, Leckie has experienced symptom relapses and still can’t even get a drink of water without help.

“I’m typing this to you from my bed, because I’m too short of breath today to get out,” they say. “This could disable me for the rest of my life, and I have no idea how much that would cost, or at what point I will lose my insurance, since it’s dependent on my employment, and I’m incapable of working.” Leckie was the sole wage earner for their five children, and was facing eviction when their partner “essentially rescued us,” allowing them to move in.

These long-term burdens are not being felt equally. At Thakur’s hospital in San Francisco, “The population [admitted] here is younger and Latinx, a disparity which reflects who gets exposed,” she says. She worries that during the pandemic, “social and structural determinants of health will just widen disparities across the board.” People of color have been disproportionately affected by the virus, in part because they are less likely to be able to work from home.

Black people are also more likely to be hospitalized if they get Covid-19, both because of higher rates of preexisting conditions — which are the result of structural inequality — and because of lack of access to health care.

“If you are more likely to be exposed because of your job, and likely to seek care later because of fear of cost, or needing to work, you’re more likely to have severe disease,” Thakur says. “As a result, you’re more likely to have long-term consequences. Depending on what that looks like, your ability to work and economic opportunities will be hindered. It’s a very striking example of how social determinants of health can really impact someone over their lifetime.”

If policies don’t support people with persistent symptoms in getting the care they need, ongoing Covid-19 challenges will deepen what’s already a clear crisis of inequality.

Iwashyna explains that a lot of extended treatment for Covid-19 patients is “going to be about interactions with health care systems that are not well-designed. The correctable problems often involve helping people navigate a horribly fragmented health care system.

“We can fix that, but we’re not going to fix that tomorrow. These patients need help now.”