/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66858616/GettyImages_1220891781.0.jpg)

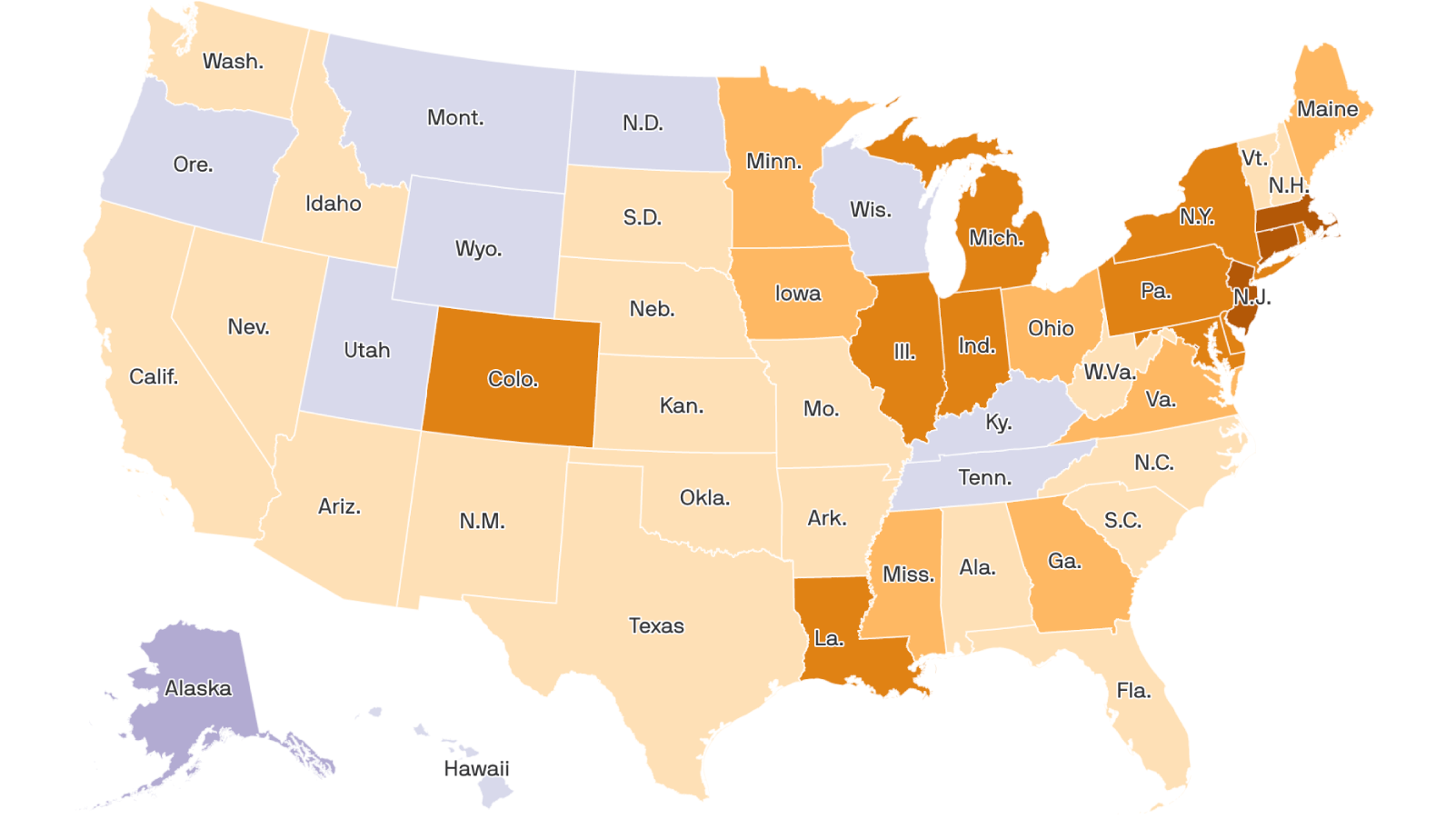

Most states still need to reduce coronavirus cases and build up their testing capacity.

All 50 states are moving to reopen their economies, at least partially, after shutting down businesses and gatherings in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

But a Vox analysis suggests that most states haven’t made the preparations needed to contain future waves of the pandemic — putting themselves at risk for a rise in Covid-19 cases and deaths should they continue to reopen.

Experts told me states need three things to be ready to reopen. State leaders, from the governor to the legislature to health departments, need to ensure the SARS-CoV-2 virus is no longer spreading unabated. They need the testing capacity to track and isolate the sick and their contacts. And they need the hospital capacity to handle a potential surge in Covid-19 cases.

More specifically, states should meet at least five basic criteria. They should see a two-week drop in coronavirus cases, indicating that the virus is actually abating. They should have fewer than four daily new cases per 100,000 people per day — to show that cases aren’t just dropping, but also below dangerous levels. They need at least 150 new tests per 100,000 people per day, letting them quickly track and contain outbreaks. They need an overall positive rate for tests below 5 percent — another critical indicator for testing capacity. And states should have more than 40 percent of their ICU beds free to actually treat an influx of people stricken with Covid-19 should it be necessary.

These metrics line up with experts’ recommendations, as well as the various policy plans put out by both independent groups and government officials to deal with the coronavirus.

Meeting these metrics doesn’t mean that a state is ready to reopen its economy — a process that describes a wide range of local and state actions. And failing them doesn’t mean a state is in immediate danger of a coronavirus outbreak if it starts to reopen; with Covid-19, there’s always an element of luck and other factors.

But with these metrics, states can gauge if they have repressed the coronavirus while building the capacity to contain future outbreaks should they come. In other words, the benchmarks show how ready states are for the next phase of the fight.

So far, most states are not there. As of May 27, just three states — Alaska, Kentucky, and New York — met four or five of the goals, which demonstrates strong progress. Thirty states hit two or three of the benchmarks. The other 17, along with Washington, DC, achieved zero or one.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20005583/coronavirus_reopen_map.png)

Even the states that have made the most progress aren’t necessarily ready to safely reopen. There’s a big difference between Alaska — which has not suffered from a high number of coronavirus cases — and New York, and no expert would say that all of New York is ready to get back to normal.

Nor do the metrics cover everything that states should do before they can reopen. They don’t show, for example, if states have the capacity to do contact tracing, in which people who came into contact with someone who’s sick with Covid-19 are tracked down by “disease detectives” and quarantined. Contact tracing is key to containing an epidemic, but states don’t track how many contact tracers they’ve hired in a standardized, readily available way.

They also don’t have ready data for health care workers’ access to personal protective equipment, such as masks and gloves — a critical measure of the health care system’s readiness that is difficult to track.

But the map gives an idea of how much progress states have made toward containing the coronavirus and keeping it contained.

States will have to follow these kinds of metrics as they reopen. If the numbers — especially coronavirus cases — go in the wrong direction again, experts said governments should be ready to bring back restrictions. If states move too quickly to reopen or respond too slowly to a turn for the worse, they could see a renewed surge in Covid-19 cases.

“Planning for reclosing is part of planning for reopening,” Mark McClellan, a health policy expert at Duke, told me. “There will be outbreaks, and there will be needs for pauses and going back — hopefully not too much if we do this carefully.”

So this will be a work in progress, at least until we get a Covid-19 vaccine or the pandemic otherwise ends, whether by natural or human means. But the metrics can at least help give states an idea of how far along they are in finally starting to open back up.

Goal 1: A sustained two-week drop in coronavirus cases

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20007678/coronavirus_cases_map.png)

What’s the goal? A 10 percent drop in daily new coronavirus cases compared to two weeks ago and a 5 percent drop in cases compared to one week ago, based on data from the New York Times.

Which states meet the goal? Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Texas — 17 states in all. Washington, DC, did as well.

Why is this important? Guidance from the White House and several independent groups emphasize that states need to see coronavirus cases drop consistently over two weeks before they can say they’re ready to begin reopening. After all, nothing shows you’re out of an outbreak like a sustained reduction in infections.

“The first and foremost [metric] is you want to have a continued decrease in cases,” Saskia Popescu, an infectious disease epidemiologist, told me. “It’s a huge piece.”

A simple reduction in cases compared to two weeks prior isn’t enough; it has to be a significant drop, and it has to be sustained over the two weeks. So for Vox’s map, states need at least a 10 percent drop in daily new cases compared to two weeks prior and at least a 5 percent drop compared to one week prior.

Reported cases can be a reflection of testing capacity: More testing will pick up more cases, and less testing will pick up fewer. So it’s important that the decrease occur while testing is either growing or already sufficient. And since states have recently boosted their testing abilities, increases in Covid-19 cases can also reflect improvements in testing.

Even after meeting this benchmark, continued caution is warranted. If a state meets the goal of a reduction in cases compared to one and two weeks ago but cases seemed to go up in recent days, then perhaps it’s not time to reopen just yet. “You have to use common sense,” Cyrus Shahpar, a director at the public health policy group Resolve to Save Lives, told me.

For states with small outbreaks, this goal is infeasible. Montana has seen around one to two new Covid-19 cases a day for several weeks. Getting that down to zero would be nice, but the current level of daily new cases isn’t a big threat to the whole state. That’s one reason Vox’s map lets states meet four or five of the five goals — in case they miss one goal that doesn’t make sense for them but hit others.

Still, the two-week reduction in cases is the most cited by experts and proposals to ease social distancing.

Goal 2: A low number of daily new Covid-19 cases

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20005708/coronavirus_cases_per_capita_map.png)

What’s the goal? Fewer than four daily new coronavirus cases per 100,000 people per day, based on data from the New York Times and Census Bureau.

Which states meet the goal? Alaska, Florida, Hawaii, Idaho, Kentucky, Maine, Michigan, Missouri, Montana, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Texas, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming — 17 states.

Why is this important? One of the best ways to know you’re getting away from a disease outbreak is to no longer see a high number of daily new infections. While there’s no universally accepted number, experts said that four daily new coronavirus cases per 100,000 people is a decent ceiling.

“If I go from one to two to three [coronavirus cases a day], it’s different than going from 1,000 to 2,000 to 3,000, even though the percent difference is the same,” Shahpar said. “That’s why you have to take into account the overall level, too.”

This number can balance out the shortcomings in other metrics on this list. For example, New York — which has suffered the worst coronavirus outbreak in the country — has seen its reported daily new coronavirus cases drop for weeks, meeting the goal of a sustained drop in cases. But since that’s coming down from a huge high, even a month of sustained decreases may not be enough. New York has to make sure it falls below a threshold of new cases, too.

At the same time, if your state is now below four daily new cases per 100,000 but it’s seen a recent uptick in cases, that’s a reason for caution. New York, after all, saw just a handful of confirmed coronavirus cases before an exponential explosion of the disease took the state to thousands of new cases a day.

But if your state is below the threshold, it’s in a pretty solid place relative to most other states.

Goal 3: High coronavirus testing capacity

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20005705/coronavirus_test_map.png)

What’s the goal? At least 150 tests per 100,000 people per day, based on data from the Covid Tracking Project and Census Bureau.

Which states meet the goal? Alaska, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Louisiana, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, and Rhode Island — for a total of 12 states.

Why is this important? Since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic, experts have argued that the US needs the capacity for about 500,000 Covid-19 tests a day. Controlling for population, that adds up to about 150 new tests per 100,000 people per day.

Testing is crucial to getting the coronavirus outbreak under control. When paired with contact tracing, testing lets officials track the scale of the outbreak, isolate the sick, quarantine those the sick came into contact with, and deploy community-wide efforts as necessary. Testing and tracing are how other countries, like South Korea and Germany, have managed to control their outbreaks and started to reopen their economies.

The idea, experts said, is to have enough surveillance to detect embers before they turn into full wildfires.

“States should be shoring up their testing capacity not just for what it looks like right now while everyone’s in their homes, but as people start to move more,” Jen Kates, the director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, told me. “As people start doing more movement, you’ll have to test more, because people are going to come into contact with each other more.”

The 500,000-a-day goal is the minimum. Some experts have recommended as many as millions of tests nationwide each day. But 500,000 is the most often-cited goal, and it’s, at the very least, a good start.

This goal is supposed to be for diagnostic tests, not antibody tests. Diagnostic tests gauge whether a person has the virus in their system and is, therefore, sick right at the moment of the test. Antibody tests check if someone ever developed antibodies to the virus to see if they had ever been sick in the past. Since diagnostic tests give a more recent gauge of the level of infection, they’re seen as much more reliable for evaluating the current state of the Covid-19 outbreak in a state.

But some states have included antibody tests in their overall counts. Experts said states shouldn’t do this. But since the data they report and the Covid Tracking Project collects is the best testing data we have, it’s hard to tease out how much antibody tests are skewing the total.

In particular, Georgia’s data suggested it met the goal of 150 daily tests per 100,000 people, but the state only started separating antibody tests from its total after the data was collected. Without the antibody tests, Georgia very likely wouldn’t meet the goal.

Some states’ numbers, like Missouri’s, also may appear significantly worse than they should due to recent efforts to decouple diagnostic testing data from antibody testing data, which can temporarily warp the overall test count.

“The virus isn’t going to care whether they were manipulating the numbers or not in order to look more favorable; it’s going to continue to spread,” Crystal Watson, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told me. “It’s better to really understand what’s going on and report that accurately.”

For states honestly reporting these numbers, though, they’re a critical measure of their ability to detect, control, and contain coronavirus outbreaks.

Goal 4: A low test-positive rate

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20005702/coronavirus_positive_rate_map.png)

What’s the goal? Below 5 percent of coronavirus tests coming back positive over the past week, based on data from the Covid Tracking Project.

Which states meet the goal? Alaska, California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming — for a total of 23 states.

Why is this important? The positive or positivity rate, which tracks how many tests come back positive for Covid-19, is another way to measure testing capacity.

Generally, a higher positive rate suggests there’s not enough testing happening. An area with adequate testing should be testing lots and lots of people, many of whom don’t have the disease or don’t show severe symptoms. The positive testing rate in South Korea, for example, is below 2 percent. High positive rates indicate only people with obvious symptoms are getting tested, so there’s not quite enough testing to match the scope of an outbreak.

Previously, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended a maximum positive rate of 10 percent. But the WHO more recently recommended 5 percent, which is in line with the rate for countries that have better managed to better control their outbreaks, like Germany, New Zealand, and South Korea. “Even lower is better,” Shahpar said.

The positive rate data is subject to the same limitations as the overall testing data from the Covid Tracking Project. So if a state includes antibody tests in its test count, it could skew the positive rate to look better than it is. States only risk hurting themselves if they do this.

Goal 5: Availability of ICU beds

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20005695/coronavirus_icu_maps.png)

What’s the goal? Below 60 percent occupancy of ICU beds in hospitals, based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Which states meet the goal? Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Connecticut, Delaware, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, Wisconsin, and Wyoming — for a total of 30 states.

Why is this important? If a pandemic hits, the health care system needs to be ready to treat the most severe cases and potentially save lives. That’s the key goal of “flattening the curve” and “raising the line,” in which social distancing helps reduce the spread of the disease so the health care system can maintain and grow its capacity to treat an influx of Covid-19 patients.

“There’s this idea that in six weeks we can open more things,” Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told me. “But the virus is still there. It’s all about making sure that the case count isn’t too immense for our hospital system to deal with.”

The aim is to avoid the nightmare scenario that Italy went through when it had more Covid-19 cases than its health care system could handle, leading to hospitals turning away even dangerously ill patients.

To gauge this, experts recommended looking at ICU capacity, with states aiming to have less than 60 percent occupancy in their ICUs.

A big limitation in the metric: It’s based on data collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of only some hospitals in each state. So it might not be fully representative of hospital capacity throughout an entire state. But it’s the best current data available, and it suggests that the majority of states meet that standard.

That’s extremely good news. It shows that America really has flattened the curve, at least for now. But it’s done that so far through extreme social distancing. If the next step is to keep the curve flattened while easing restrictions, that will require meeting the other metrics on this list.

Hitting the benchmarks is the beginning, not the end

Vox’s map is just one way of tracking success against the coronavirus. Other groups have come up with their own measures, including Covid Act Now, Covid Exit Strategy, and Test and Trace. Vox’s model uses more up-to-date data than some of these other examples, while focusing not just on the state of the pandemic but states’ readiness to contain Covid-19 outbreaks in the future.

Very few states hit all the marks recommended by experts. But even those that do shouldn’t consider the pandemic over. They should continue to improve — for example, getting the positive rate below even 1 percent, as in New Zealand — and look at even more granular metrics, such as at the city or county level.

Meeting the benchmarks, however, indicates a state is better equipped to contain future coronavirus outbreaks as it eases previous restrictions.

Experts emphasized that states have to keep hitting all these goals week after week and day after day — Covid-19 cases must remain low, testing ability needs to stay high, and hospital capacity should be good enough for an influx of patients — until the pandemic is truly over, whether thanks to a vaccine or other means. Otherwise, a future wave of coronavirus cases, as seen in past pandemics, could kill many more people.

“You need to have all the metrics met,” Popescu said. “This needs to be a very incremental, slow process to ensure success.”

And if the numbers do start trending in the wrong direction, states should be ready to shut down at least some parts of the economy again. Maybe not as much as before, as we learn which places are truly at risk of increasing spread. But experts caution that future shutdowns will likely be necessary to some extent.

“I do worry we’re going to see surges of cases and hot spots,” Watson said. “We do need to keep pushing on building those capacities. … Otherwise, we’re just rolling the dice on the spread of the virus. It’s better if we have more control of the spread.”

That’s another reason these metrics, along with broader coronavirus surveillance, are so important: They not only help show how far along states are in dealing with their current Covid-19 outbreaks, but will help track progress to stop and prevent future crises as well.