https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/how-america-skimps-healthcare-robert-pearl-m-d–p1qnc/

Not long ago, I opened a new box of cereal and found a lot fewer flakes than usual. The plastic bag inside was barely three-quarters full.

This wasn’t a manufacturing error. It was an example of shrinkflation.

Following years of escalating prices (to offset higher supply-chain and labor costs), packaged-goods producers began facing customer resistance. So, rather than keep raising prices, big brands started giving Americans fewer ounces of just about everything—from cereal to ice cream to flame-grilled hamburgers—hoping no one would notice.

This kind of covert skimping doesn’t just happen at the grocery store or the drive-thru lane. It’s been present in American healthcare for more than a decade.

What Happened To Healthcare Prices?

With the passage of the Medicare and Medicaid Act in 1965, healthcare costs began consuming ever-higher percentages of the nation’s gross domestic product.

In 1970, medical spending took up just 6.9% of the U.S. GDP. That number jumped to 8.9% in 1980, 12.1% in 1990, 13.3% in 2000 and 17.2% in 2010.

This trajectory is normal for industrialized nations. Most countries follow a similar pattern: (1) productivity rises, (2) the total value of goods and services increases, (3) citizens demand better care, newer drugs, and more access to doctors and hospitals, (4) people pay more and more for healthcare.

But does more expensive care equate to better care and longer life expectancy? It did in the United States from 1970 to 2010. Longevity leapt nearly a decade as healthcare costs rose (as a percentage of GDP).

Then American Healthcare Hit A Ceiling

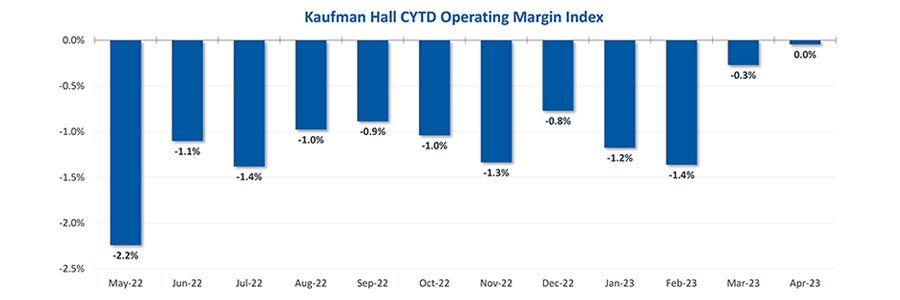

Beginning in 2010, something unexpected happened. Both of these upward trendlines—healthcare inflation and longevity—flattened.

Spending on medical care still consumes roughly 17% of the U.S. GPD—the same as 2010. Meanwhile, U.S. life expectancy in 2020 (using pre-pandemic data) was 77.3 years—about the same as in 2010 when the number was 78.7 years.

How did these plateaus occur?

Skimping On U.S. Healthcare

With the passage of the Affordable Care Act of 2010, healthcare policy experts hoped expansions in health insurance coverage would lead to better clinical outcomes, resulting in fewer heart attacks, strokes and cancers. Their assumption was that fewer life-threatening medical problems would bring down medical costs.

That’s not what happened. Although the rate of healthcare inflation did, indeed, slow to match GDP growth, the cost decreases weren’t from higher-quality medical care, drug breakthroughs or a healthier citizenry. Instead, it was driven by skimping.

And as a result of skimping, the United States fell far behind its global peers in measures of life expectancy, maternal mortality, infant morality, and deaths from avoidable or treatable conditions.

To illustrate this, here are three ways that skimping reduces medical costs but worsens public health:

1. High-Deductible Health Insurance

In the 20th century, traditional health insurance included two out-of-pocket expenses. Patients paid a modest upfront fee at the point of care (in a doctor’s office or hospital) and then a portion of the medical bill afterward, usually totaling a few hundred dollars.

Both those numbers began skyrocketing around 2010 when employers adopted high-deductible insurance plans to offset the rising cost of insurance premiums (the amount an insurance company charges for coverage). With this new model, workers pay a sizable sum from their own pockets—up to $7,050 for single coverage and $14,100 for families—before any health benefits kick in.

Insurers and businesses argue that high-deductible plans force employees to have more “skin in the game,” incentivizing them to make wiser healthcare choices.

But instead of promoting smarter decisions, these plans have made care so expensive that many patients avoid getting the medical assistance they need. Nearly half of Americans have taken on debt due to medical bills. And 15% of people with employer-sponsored health coverage (23 million people) have seen their health get worse because they’ve delayed or skipped needed care due to costs.

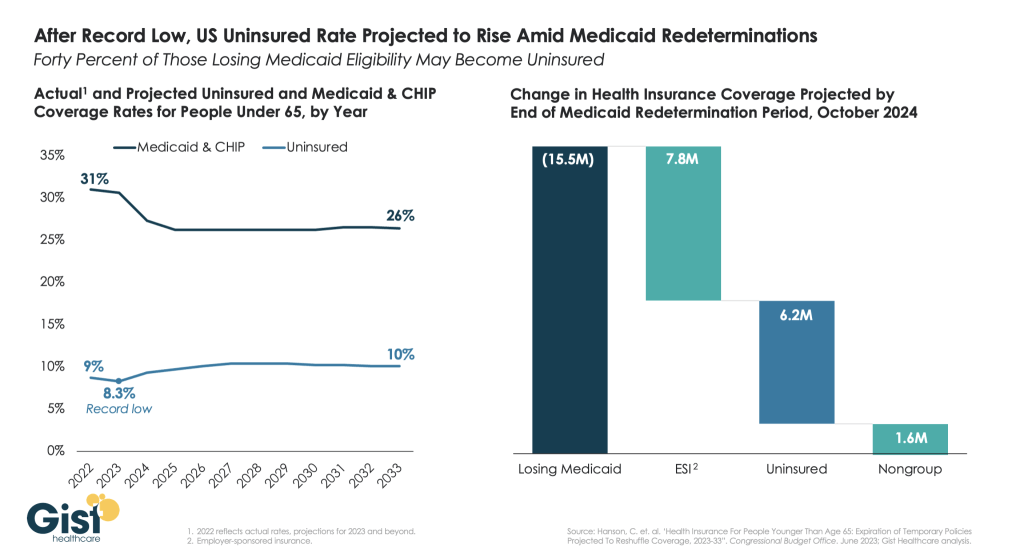

And when it comes to Medicaid, the government-run health program for individuals living in poverty, doctors and hospitals are paid dramatically lower rates than with private insurance.

As a result, even though the nation’s 90 million Medicaid enrollees have health insurance, they find it difficult to access care because an increasing number of physicians won’t accept them as patients.

2. Cost Shifting

Unlike with private insurers, the U.S. government unilaterally sets prices when paying for healthcare. And in doing so, it transfers the financial burden to employers and uninsured patients, which leads to skimping.

To understand how this happens, remember that hospitals pay the same amount for doctors, nurses and medicines, regardless of how much they are paid (by insurers) to care for a patient. If the dollars reimbursed for some patients don’t cover the costs, then other patients are charged more to make up the difference.

Two decades ago, Congress enacted legislation to curb federal spending on healthcare. This led Medicare to drastically reduce how much it pays for inpatient services. Consequently, private insurers and uninsured patients now pay double and sometimes triple Medicare rates for hospital services, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation report.

These higher prices generate heftier out-of-pocket expenses for privately insured individuals and massive bills for the uninsured, forcing millions of Americans to forgo necessary tests and treatments.

3. Delaying, Denying Care

Insurers act as the bridge between those who pay for healthcare (businesses and the government) and those who provide it (doctors and hospitals). To sell coverage, they must design a plan that (a) payers can afford and (b) providers of care will accept.

When healthcare costs surge, insurers must either increase premiums proportionately, which payers find unacceptable, or find ways to lower medical costs. Increasingly, insurers are choosing the latter. And their most common approach to cost reduction is skimping through prior authorization.

Originally promoted as a tool to prevent misuse (or overuse) of medical services and drugs, prior authorization has become an obstacle to delivering excellent medical care. Insurers know that busy doctors will hesitate to recommend costly tests or treatments likely to be challenged. And even when they do, patients weary of the wait will abandon treatment nearly one-third of the time.

This dynamic creates a vicious cycle: costs go down one year, but medical problems worsen the next year, requiring even more skimping the third year.

The Real Cost Of Healthcare Skimping

Federal actuaries project that healthcare expenses will rise another $3 trillion over the next eight years, consuming nearly 20% of the U.S. GDP by 2031.

But given the challenges of ongoing inflation and rapidly rising national debt, it’s more plausible that healthcare’s share of the GDP will remain at around 17%.

This outcome won’t be due to medical advancements or innovative technologies, but rather the result of greater skimping.

For example, consider that Medicare decreased payments to doctors 2% this year with another 3.3% cut proposed for 2024. And this year, more than 10 million low-income Americans have lost Medicaid coverage as states continue rolling back eligibility following the pandemic. And insurers are increasingly using AI to automate denials for payment.

Currently, the competitive job market has business leaders leery of cutting employee health benefits. But as the economy shifts, employees should anticipate paying even more for their healthcare.

The truth is that our healthcare system is grossly inefficient and financially unsustainable. Until someone or something disrupts that system, replacing it with a more effective alternative, we will see more and more skimping as our nation struggles to restrain medical costs.

And that will be dangerous for America’s health.