Category Archives: Operating Expense Reduction

Kaiser Permanente reports $2.1B profit, 2.9% operating margin in Q2 2023

Kaiser Permanente built on 2023’s strong start with $2.08 billion of net income during the quarter ended June 30, bringing its midyear total to about $3.29 billion, the integrated system announced late Friday.

Operating income was also strong at $741 million (2.9% margin) and raised the organization’s six-month performance to $974 million (1.9% margin).

The numbers are both a sequential improvement and a stark turnaround from 2022. By the midpoint of that year, Kaiser Permanente was reporting a $1.3 billion net loss for the quarter and an $89 million operating gain (0.4% margin). Across 2022’s first half, the system had been down a total of $2.26 billion and added just $17 million from operations (0.0% margin).

The Oakland, California-based nonprofit is likely safe from repeating the nearly $4.5 billion net loss and $1.3 billion operating loss of full-year 2022.

Leadership, however, noted that the integrated system historically sees higher operating margins during the first half of the year “due in part to the annual enrollment cycle and seasonal care.”

“Our second-quarter financial results reflect operational improvements that, together with our ongoing expense reduction efforts, will help us face additional financial pressures in the second half of the year,” Kathy Lancaster, executive vice president and chief financial officer at Kaiser Permanente, said in a release. “The process of building our financial performance back to pre-pandemic levels requires that we continue to redesign our cost structure to support investments in our facilities, technology and people while staying competitive in a dynamic healthcare marketplace.”

Kaiser Permanente reported $25.17 billion in operating revenues for the second quarter, a 7.2% increase year over year. Operating expenses increased 4.5% year-over-year to $24.42 billion.

“Like all health systems, Kaiser Permanente is experiencing ongoing cost headwinds and volatility driven by inflation, labor shortages, and the lingering effects of the pandemic on access to care and service,” the system wrote in a release.

Kaiser Permanente’s membership has increased by more than 81,000 members since the start of the year and sits at almost 12.7 million as of June 30. The organization noted that it has kicked off an outreach campaign for Medicaid members “to ensure they have critical enrollment information as states go through the mandated process of eligibility redetermination.”

The largest impact on Kaiser Permanente’s bottom line came from investments. Owing to “favorable financial market conditions,” the organization recorded $1.34 billion in “other income and expense,” nearly a full reversal of the $1.39 billion loss on the same line item it’d logged during the same period last year.

The system’s capital spending reached $824 million for the quarter, which was up from $789 million during the second quarter of 2022 but a pullback from the first quarter of 2023’s $930 million.

“The post-pandemic financial pressures have led many in the industry to cut back on care and service,” CEO Greg Adams said in an accompanying statement. “At Kaiser Permanente, we remain focused on improving access and affordability for our patients, members and communities, which requires continued investment in care and coverage. … I want to thank all employees and physicians for turning the disruptions and challenges of the past three years into opportunities to make our healthcare system stronger and more equitable, with improved outcomes for all.”

Kaiser Permanente is the largest nonprofit health system in the country by revenue with more than $95 billion in annual revenues. As of June 30, it spanned 39 hospitals, 622 medical offices and 43 clinics in addition to its millions of covered health plan members.

Earlier in the year the system highlighted efforts to trim administrative and discretionary spending as well as a workforce push that improved clinical hiring by 15% year over year. It is in the midst of negotiating a new labor contract covering 85,000 unionized healthcare workers who are seeking workforce development investments and higher staffing levels across clinical settings.

The organization is also working toward its high-profile acquisition of fellow integrated nonprofit Geisinger Health, which Kaiser Permanente said would be the first step toward a cross-country value-based care organization called Risant Health.

Hospitals still struggling to retain talent

https://mailchi.mp/c02a553c7cf6/the-weekly-gist-july-28-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

Of all the pandemic’s impacts still felt today, disruptions to the healthcare workforce and rising labor costs may be most impactful to current health system operations.

Over the next three editions of the Weekly Gist, we’ll be exploring the lingering effects of this workforce crisis, with a focus on nurse staffing and recruitment.

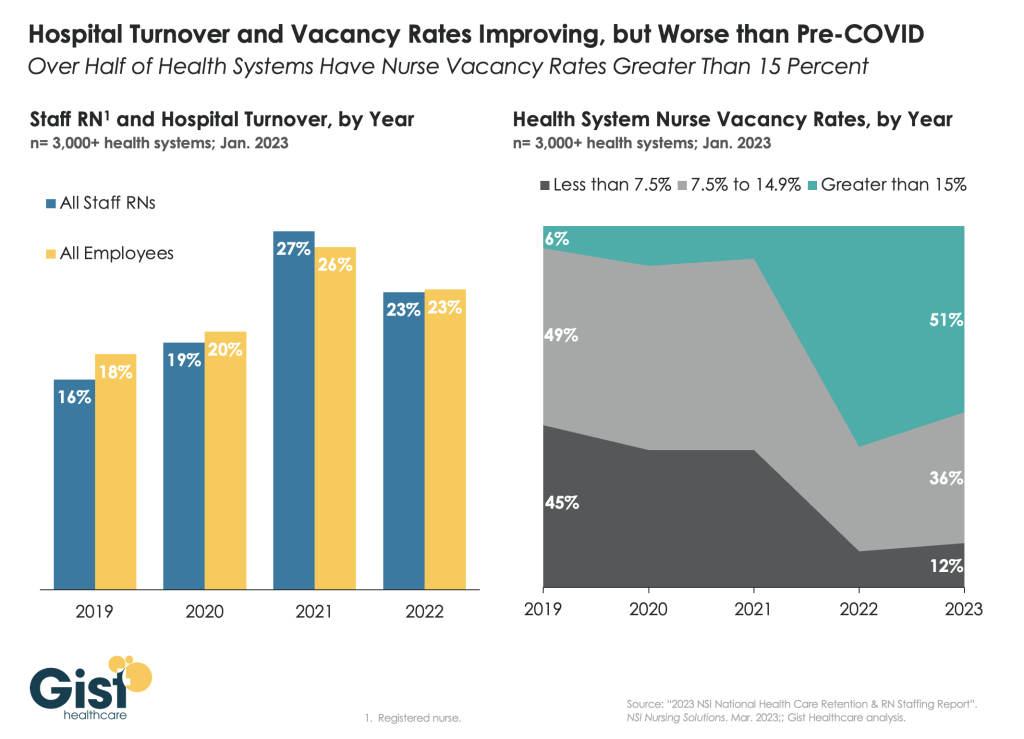

In this week’s graphic, we use data from the 2023 NSI National Health Care Retention Report to show how hospital turnover and vacancy rates have changed over the past several years.

While wage increases helped reduce hospital registered nurse (RN) turnover rates from 27 percent in 2021 to 23 percent in 2022, nurses—along with hospital employees in general—are still changing jobs at higher rates than before the pandemic.

Over half of all hospitals still face nurse vacancy rates above 15 percent, a slight improvement from 2022 but still far more than before the pandemic.

While the worst of nursing turnover appears to have passed, the “rebasing” of wages (for nursing, 27 percent higher compared to 2019) will provide ongoing pressure to strained hospital margins.

Comments on Current Management Issues in the Healthcare C-Suite: Management of Labor in Trying Financial Circumstances

Peter Drucker, the hall of fame management guru, once famously said that the hardest business organization to run in America was a hospital. If that comment was true so many years ago, imagine what Drucker would have to say about the difficulty of hospital management right now.

Hospital financial performance suffered significantly in 2022 and recovery during 2023 has been quite slow. This trend suggests the question,

“What steps are hospital C-suites taking to recover pre-Covid financial stability?”

Erik Swanson manages all analyses for our monthly Kaufman Hall Flash Report and he and I speculated that an industry-wide hospital recovery could not be achieved without reductions in force across the hospital ecosystem. Some research on our part determined that no official organization tracks hospital layoffs over time but we wondered if we could use our Flash Report data, which is provided to us by Syntellis Performance Solutions, to reach an informed conclusion.

What we were able to do was prepare three types of charts, as follows:

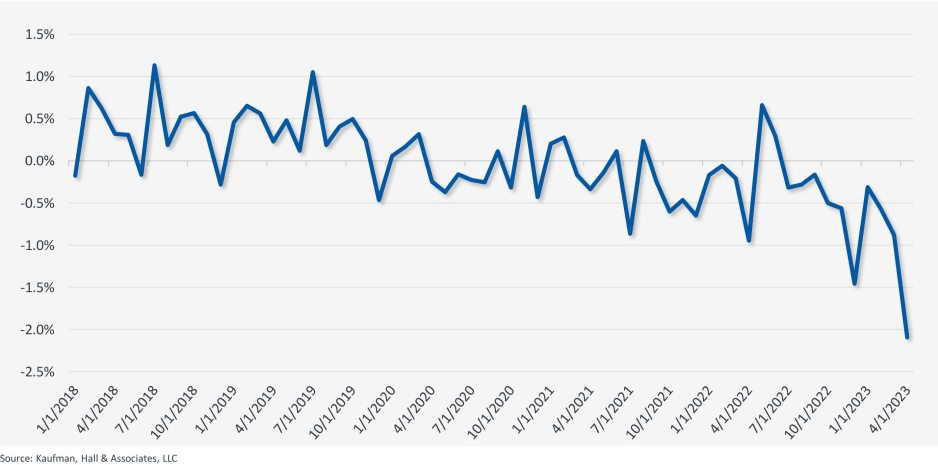

The first chart measures net employee percentage change by month. This chart shows whether overall hospital employment is increasing or decreasing over time and by how much.

The second chart attempts to establish the median turnover for hospitals over an annual period and then measure the deviation from that turnover rate. A greater deviation from what might be termed “normal turnover” suggests that an increasing number of hospitals are using reductions in force to more quickly reduce the cost of doing business.

The third chart shows average FTEs per occupied bed on a comparative basis looking at month-to-month and year-to-year statistics.

The first chart, Net Employee Percentage Change by Month, begins at January 1, 2018, and continues to March 1, 2023 (Figure 1). Overall additions to hospital employment remained generally positive through January 1, 2020. Overall hospital employment then went generally negative from March 2020 (the onset of Covid restrictions) to March 2022. The reductions in hospital employees during this period were likely the result of the “great resignation” during the worst of the Covid pandemic. But then, from July 2022 to March 2023, overall hospital employees demonstrated by the Flash Report dropped dramatically with an overall 2% decrease at the March 2023 date. This statistic suggests more than simply increased hospital turnover, but rather a formal layoff process initiated across many hospital organizations, along with aggressive management of contract labor.

Figure 1: Net Employee Percentage Change by Month

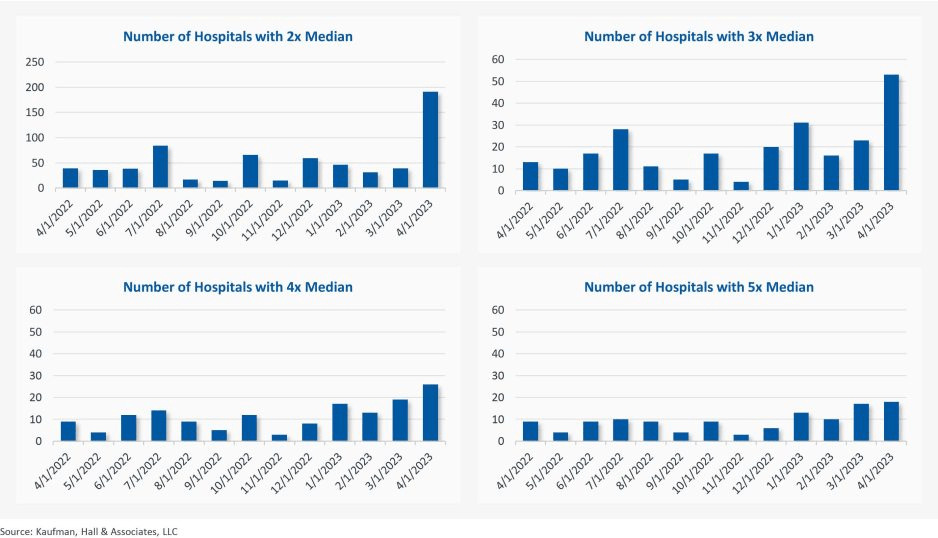

The second chart demonstrates the deviation from expected turnover at levels of 2x, 3x, 4x, and 5x by number of hospitals (Figure 2). No matter which measure you examine, the deviation of employees from expected turnover spiked significantly in April 2023 and even more so in May 2023. This again suggests the aggressive management of labor costs that likely could not occur without the intentional reduction of actual positions and/or the cost of these positions.

Figure 2: Number of Hospitals with Deviations from Expected Turnover at 2x, 3x, 4x, and 5x the Median

The last chart provides a remarkable set of observations (Figure 3). FTEs per adjusted occupied bed (AOB) declined by 8.3% between June 2023 and July 2023. The year-over-year variation for July 2023 was a decline of 11.01%. Our data further reveals that the FTE per AOB statistic has declined in five of the past six months on a month-over-month basis.

Figure 3: Median Change in FTEs per Adjusted Occupied Bed by Month

The conclusion here is that the return of the hospital industry to pre-Covid financial results has been no walk in the park. 2022 was, of course, a dismal financial year for the hospital industry. And while 2023 has shown improvement, the usual management steps to recovery have been only moderately effective. The data and analysis above demonstrate that C-suites across America are moving to stronger measures to assure the financial survivability and competitiveness of their organizations.

There is no revenue solve here, or at least not in the current environment: costs must come down and they must come down materially. From the sense and the trend of the data it would seem that hospital executive teams get the joke.

California system’s 10.2% operating margin bucks national trend

Mountain View, Calif.-based El Camino Health ended the first quarter with an impressive operating margin of 10.2 percent when many health systems saw their margins hover above zero or fall into the red. The system’s revenue for the quarter totaled $131,290.

For the nine months ended March 31, the two-hospital system posted an operating gain of $141.4 million on revenue of just over $1 billion.

However, like most health systems, El Camino’s expenses are substantially higher than the same period last year, increasing 10.6 percent year over year for the nine months ending March 31, 2023, to $881.9 million.

The system is making a conscious effort to march down labor costs while also placing a significant emphasis on retention. In June, El Camino agreed a deal to increase pay for nurses by 16 percent over three years.

“Like nearly all hospitals, our nursing staff comprises the largest part of our workforce. With the recruitment of a single nurse estimated to be nearly $60,000, our primary strategy to reduce labor costs is to focus on decreasing turnover,” El Camino CEO Dan Woods told Becker’s.

“Our turnover rate for nurses is just about 8 percent while the turnover rate nationally is still running at 22 percent.”

In March, the system also received a credit rating upgrade from Moody’s, which noted the system’s “superlative cash metrics and operating performance.” Fitch Ratings also revised El Camino’s outlook to positive in February, noting that the system has a history of generating double-digit operating EBITDA margins, driven by a solid market position that features strong demographics and a very healthy payer mix.

17 health systems zeroing in on exec teams, administration in 2023

At least 17 health systems announced changes to executive ranks and administration teams in 2023.

The changes come as hospitals continue to grapple with financial challenges, leading some organizations to cut jobs and implement other operational adjustments.

The following changes were announced within the last two months and are summarized below, with links to more comprehensive coverage of the changes.

1. Middletown, N.Y.-based Garnet Health laid off 49 employees, including 25 leaders, to offset recent operating losses. The reductions represent 1.13 percent of the organization’s total workforce and $13 million in salaries and benefits.

2. Greensburg, Pa.-based Independence Health System laid off 53 employees and has cut 226 positions — including resignations, retirements and elimination of vacant positions — since January, The Butler Eagle reported June 28. The 226 reductions began at the executive level, with 13 manager positions terminated in March.

3. Coral Gables-based Baptist Health South Florida is offering its executives at the director level and above a “one-time opportunity” to apply for voluntary separation, according to a June 29 Miami Herald report. Decisions on buyout applications will be made during the summer.

4. MultiCare Health System, a 12-hospital organization based in Tacoma, Wash., will lay off 229 employees, or about 1 percent of its 23,000 staff members, including about two dozen leaders, as part of cost-cutting efforts, the health system said June 29. The layoffs primarily affect support departments, such as marketing, IT and finance.

5. Seattle Children’s is eliminating 135 leader roles, citing financial challenges. The management restructuring and reduction affects 1.5 percent of employees across the organization.

6. Bonnie Panlasigui was tapped as the first president of Summa Health System Hospitals.This new role was first announced in October as the Akron, Ohio-based system made 10 changes to its executive team: reshuffling three leaders’ roles, adding three positions and eliminating four.

7. Allentown, Pa.-based Lehigh Valley Health Network named two new regional and hospital presidents. Bob Begliomini, PharmD, was appointed president of Lehigh Valley Hospital-Cedar Crest campus in Allentown, according to a news release shared with Becker’s. He will also lead the health system’s Lehigh region, which includes four hospital campuses. Jim Miller, CRNA, was selected to replace Mr. Begliomini as president of the Muhlenberg hospital. He was also named president of the health system’s Northampton region, which includes three hospitals, Muhlenberg being one of them.

8. McLaren St. Luke’s Hospital in Maumee, Ohio, will lay off 743 workers, including 239 registered nurses, when it permanently closes this spring. Other affected roles include physical therapists, radiology technicians, respiratory therapists, pharmacists and pharmacy support staff, and nursing assistants. The hospital’s COO is also affected, and a spokesperson for McLaren Health Care told Becker’s other senior leadership roles are also affected.

9. Habersham Medical Center in Demorest, Ga., laid off four executives. The layoffs were part of cost-cutting measures before the hospital joined Gainesville-based Northeast Georgia Health System.

10. Grand Forks, N.D.-based Altru Health announced it would trim its executive team as its new hospital project moves forward. The health system is trimming its executive team from nine to six and incentivizing 34 other employees to take early retirement.

11. Scripps Health eliminated 70 administrative roles, according to WARN documents filed by the San Diego-based health system in March. The layoffs took effect May 8 and affect corporate positions in San Diego and La Jolla, Calif.

12. Columbia-based University of Missouri Health Care announced it would eliminate five hospital leadership positions across the organization. According to MU Health Care, the move is a result of restructuring “to better support patients and the future healthcare needs of Missourians.”

13. Winston-Salem, N.C.-based Novant Health laid off about 50 workers, including C-level executives, the health system confirmed to Becker’s March 29. The layoffs affected Jesse Cureton, the health system’s executive vice president and chief consumer officer since 2013; Angela Yochem, its executive vice president and chief transformation and digital officer since 2020; and Paula Dean Kranz, vice president of innovation enablement and executive director of the Novant Health Innovation Labs.

14. Philadelphia-based Penn Medicine announced that it would eliminate administrative positions. The change is part of a reorganization plan to save the health system $40 million annually, the Philadelphia Business Journal reported March 13. Kevin Mahoney, CEO of the University of Pennsylvania Health System, told Penn Medicine’s 49,000 employees changes include the elimination of a “small number of administrative positions which no longer align with our key objectives,” according to the publication.

15. Sovah Health, part of Brentwood, Tenn.-based Lifepoint Health, eliminated the COO positions at its Danville and Martinsville, Va., campuses. The responsibilities of both COO roles are now spread across members of the existing administrative team.

16. Valley Health, a six-hospital health system based in Winchester, Va., eliminated 31 administrative positions. The job cuts are part of the consolidation of the organization’s leadership team and administrative roles. They were announced internally on Feb. 28.

17. Roseville, Calif.-based Adventist Health announced it would transition from seven networks of care to five systemwide to reduce costs and strengthen operations. Under the reorganization, the health system will have separate networks for Northern California, Central California, Southern California, Oregon and Hawaii. The reorganization will result in job cuts, including reducing administration by more than $100 million.

Cartoon – Eliminate Redundancies

Taking a historical view of hospital operating margins

https://mailchi.mp/cc1fe752f93c/the-weekly-gist-july-14-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

So far, 2023 is shaping up to be a slightly better year for hospital performance, but it comes on the heels of unprecedented financial difficulties for the sector.

In the graphic above, we evaluated nearly 30 years of historical data from Kaufman Hall and the American Hospital Association to provide a broader perspective on hospital operating margins over time. 2020 and 2022 have been the only years in which a majority of hospitals—53 percent—posted a negative operating margin.

During the most comparable periods of recent economic hardship, the “dot-com bubble burst” of the late 1990s and the 2009 Great Recession, the share of hospitals with negative operating margins amounted to only 42 and 32 percent, respectively.

With this context, hospitals’ current financial distress is more severe than anything we’ve seen in the past three decades.

Healthcare is clearly no longer recession-proof: a four percent operating margin—the level needed for health systems to not only sustain operations but also invest in growth—feels even more elusive as labor costs remain high, surgical care continues to shift to outpatient settings, the second half of the Baby-Boom generation ages into Medicare, and deep-pocketed competitors compete for profitable services.

9 recent health system downgrades and outlook revisions

Here is a summary of recent credit downgrades and outlook revisions for hospitals and health systems.

The downgrades and downward revisions reflect continued operating challenges many nonprofit systems are facing, with multiyear recovery processes expected.

Downgrades:

Yale New Haven (Conn.) Health: Operating weakness and elevated debt contributed to the downgrade of bonds held by Yale New Haven (Conn.) Health, Moody’s said May 5. The bond rating slipped from “Aa3” to “A1,” and the outlook was revised to stable from negative.

The system saw a second downgrade as its default rating and that on a series of bonds were revised one notch to “A+” from “AA-” amid continued operating woes, Fitch said June 28.

Not only have there been three straight years of such challenges, but the operating environment continues to cast a pall into the second quarter of the current fiscal year, Fitch said.

UC Health (Cincinnati): The system was downgraded on a series of bonds, Moody’s said May 10.

The move, which involved a lowering from a “Baa2” to “Baa3” grade, refers to such bonds with an overall value of $580 million.

In February, UC Health suffered a similar downgrade from “A” to “BBB+” on its overall rating and on some bonds because of what S&P Global termed “significantly escalating losses.”

UNC Southeastern (Lumberton, N.C.): The system, which is now part of the Chapel Hill, N.C.-based UNC Health network, saw its ratings on a series of bonds downgraded to “BB” amid operating losses and sustained weakness in its balance sheet, S&P Global said June 23.

While UNC Southeastern reported an operating loss of $74.8 million in fiscal 2022, such losses have continued into fiscal 2023 with a $15 million loss as of March 31, S&P Global said. The system had earlier been placed on CreditWatch but that was removed with this downgrade.

Butler (Pa.) Health: The system, now merged with Greensburg, Pa.-based Excela Health to form Independence Health System, saw its credit rating downgraded significantly, falling from “A” to “BBB.”

The move reflects continued operating challenges and low patient volumes, Fitch said June 26.

Such operating challenges, including low days of cash on hand, could result in potential default of debt covenants, Fitch warned.

Outlook revisions:

Redeemer Health (Meadowbrook, Pa.): The system had its outlook revised to negative amid “persistent operating losses,” Fitch Ratings said June 14. The health system, anchored by a 260-bed acute care hospital, reported a $37 million operating loss in the nine months ending March 31, Fitch said.

Thomas Jefferson University (Philadelphia): The June 9 downward revision of its outlook, which includes both the health system and the university’s academic sector, was due to sustained operating weakness, S&P Global said.

IU Health (Indianapolis): While it saw ratings affirmed at “AA,” the 16-hospital system had its outlook downgraded amid persistent inflationary pressures and large capital expense, Fitch said May 31.

UofL Health (Louisville, Ky.): Slumping operating income and low days of cash on hand (42.8 as of March 31) contributed to S&P Global revising its outlook for the six-hospital system to negative May 24.

The Hospital Makeover—Part 2

America’s hospitals have a $104 billion problem.

That’s the amount you arrive at if you multiply the number of physicians employed by hospitals and health systems (approximately 341,200 as of January 2022, according to data from the Physicians Advocacy Institute and Avalere) by the median $306,362 subsidy—or loss—reported in our Q1 2023 Physician Flash Report.

Subsidizing physician employment has been around for a long time and such subsidies were historically justified as a loss leader for improved clinical services, the potential for increased market share, and the strengthening of traditionally profitable services.

But I am pretty sure the industry did not have $104 billion in losses in mind when the physician employment model first became a key strategic element in the hospital operating model. However, the upward reset in expenses brought on by the pandemic and post-pandemic inflation has made many downstream hospital services that historically operated at a profit now operate at breakeven or even at a loss. The loss leader physician employment model obviously no longer works when it mostly leads to more losses.

This model is clearly broken and in demand of a near-term fix. Perhaps the critical question then is how to begin? How to reconsider physician employment within the hospital operating plan?

Out of the box, rethink the physician productivity model. Our most recent Physician Flash Report data shows that for surgical specialties, there was a median $77 net patient revenue per provider wRVU. For the same specialties, there was a median $80 provider paid compensation per provider wRVU. In other words, before any other expenses are factored in, these specialties are losing $3 per wRVU on paid compensation alone. Getting providers to produce more wRVUs only makes the loss bigger.

It’s the classic business school 101 problem.

If a factory is losing $5 on every widget it produces, the answer is not to produce more widgets. Rather, expenses need to come down, whether that is through a readjustment of compensation, new compensation models that reward efficiency, or the more effective use of advanced practice providers.

Second, a number of hospital CEOs have suggested to me that the current employed physician model is quite past its prime. That model was built for a system of care that included generally higher revenues, more inpatient care, and a greater proportion of surgical vs. medical admissions. But overall, these trends were changing and then were accelerated by the Covid pandemic. Inpatient revenue has been flat to down. More clinical work continues to shift to the outpatient setting and, at least for the time being, medical admissions have been more prominent than before the pandemic.

Taking all this into account suggests that in many places the employed physician organizational and operating model is entirely out of balance. One would offer the calculated guess that there are too many coaches on the team and not enough players on the field. This administrative overhead was seemingly justified in a different loss leader environment but now it is a major contributor to that $104 billion industry-wide loss previously calculated.

Finally, perhaps the very idea of physician employment needs to be rethought.

My colleagues Matthew Bates and John Anderson have commented that the “owner” model is more appealing to physicians who remain independent then the “renter” model. The current employment model offers physicians stability of practice and income but appears to come at the cost of both a loss of enthusiasm and lost entrepreneurship. The massive losses currently experienced strongly suggest that new models are essential to reclaim physician interest and establish physician incentives that result in lower practice expenses, higher practice revenues, and steadily reduced overall subsidies.

Please see this blog as an extension of my last blog, “America’s Hospitals Need a Makeover.” It should be obvious that by analogy we are not talking about a coat of paint here or even new appliances in the kitchen.

The financial performance of America’s hospitals has exposed real structural flaws in the healthcare house. A makeover of this magnitude is going to require a few prerequisites:

- Don’t start designing the renovation unless you know specifically where profitability has changed within your service lines and by explicitly how much. Right now is the time to know how big the problem is, where those problems are located, and what is the total magnitude of the fix.

- The Board must be brought into the discussion of the nature of the physician employment problem and the depth of its proposed solutions. Physicians are not just “any employees.” They are often the engine that runs the hospital and must be afforded a level of communication that is equal to the size of the financial problem. All of this will demand the Board’s knowledge and participation as solutions to the physician employment dilemma are proposed, considered, and eventually acted upon.

The basic rule of home renovation applies here as well: the longer the fix to this problem is delayed the harder and more expensive the project becomes. The losses set out here certainly suggest that physician employment is a significant contributing factor to hospitals’ current financial problems overall. It would be an understatement to say that the time to get after all of this is right now.