A surge in COVID-19 infections has swept the country this summer, upending travel plans and bringing fevers, coughs and general malaise. It shows no immediate sign of slowing.

While most of the country and the federal government has put the pandemic in the rearview mirror, the virus is mutating and new variants emerging.

Even though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) no longer tracks individual infection numbers, experts think it could be the biggest summer wave yet.

So far, the variants haven’t been proven to cause a more serious illness, and vaccines remain effective, but there’s no certainty about how the virus may yet change and what happens next.

The highest viral activity right now is in the West, according to wastewater data from the CDC, but a “high” or “very high” level of COVID-19 virus is being detected in wastewater in almost every state. And viral levels are much higher nationwide than they were this time last year and started increasing earlier in the summer.

Wastewater data is the most reliable method of tracking levels of viral activity because so few people test, but it can’t identify specific case numbers.

Part of the testing decline can be attributed to pandemic fatigue, but experts said it’s also an issue of access. Free at-home tests are increasingly hard to find. The government isn’t distributing them, and private insurance plans have not been required to cover them since the public health emergency ended in 2023.

COVID has spiked every summer since the start of the pandemic. Experts have said the surge is being driven by predictable trends like increased travel and extreme hot weather driving more people indoors, as well as by a trio of variants that account for nearly 70 percent of all infections.

Vaccines and antivirals can blunt the worst of the virus, and hospital are no longer being overwhelmed like in the earliest days of the pandemic.

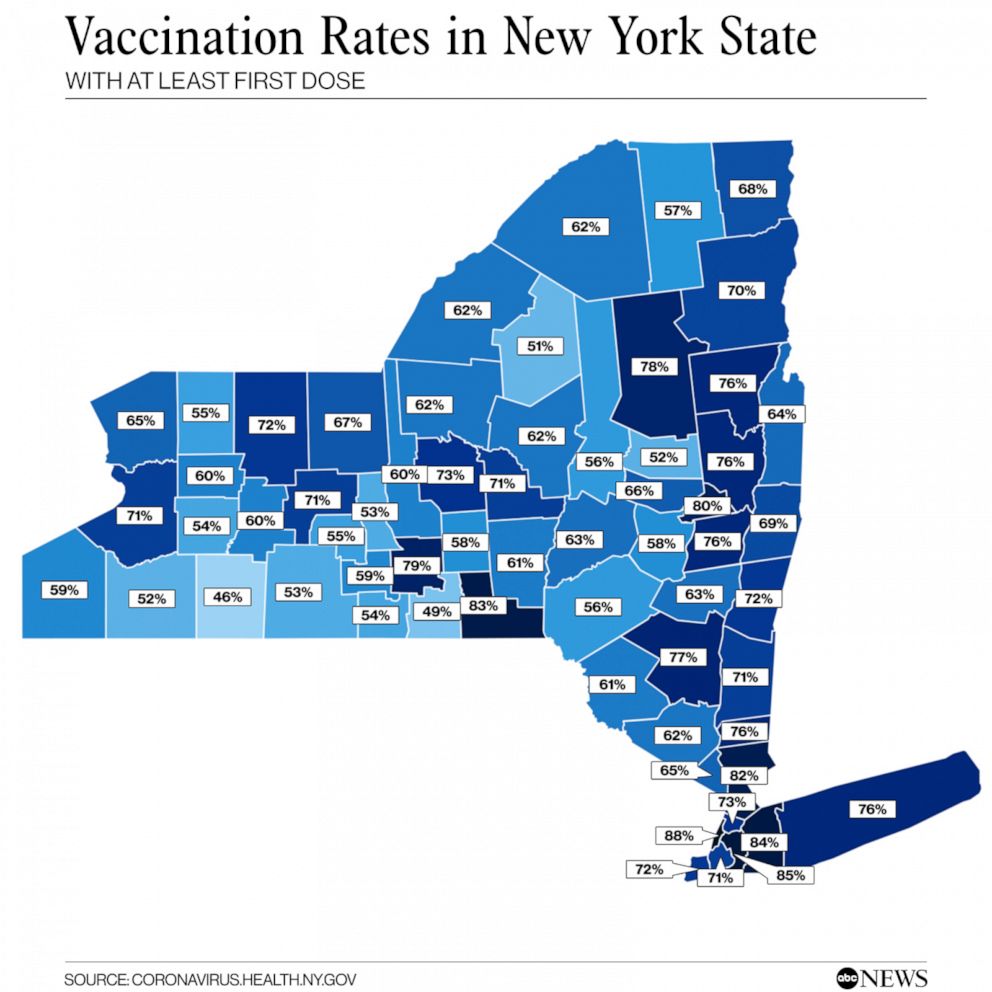

But there remains a sizeable number of people who are not up-to-date on vaccinations. There are concerns that diminished testing and low vaccination rates could make it easier for more dangerous variants to take hold.

“One of the things that’s distinctive about this summer is that the variants out there are extraordinarily contagious, so they’re spreading very, very widely, and lots of people are getting mild infections, many more than know it, because testing is way down,” said William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University.

That contagiousness means the virus is more likely to find the people most vulnerable — people over 65, people with certain preexisting conditions, or those who are immunocompromised.

In a July interview with the editor-in-chief of MedPage Today, the country’s former top infectious diseases doctor, Anthony Fauci, said people in high-risk categories need to take the virus seriously, even if the rest of the public does not.

“You don’t have to immobilize what you do and just cut yourself off from society,” Fauci said. “But regardless of what the current recommendations are, when you are in a crowded, closed space and you are an 85-year-old person with chronic lung disease or a 55-year-old person who’s morbidly obese with diabetes and hypertension, then you should be wearing a mask when you’re in closed indoor spaces.”

Schaffner said hospitalizations have been increasing in his region for at least the past five weeks, which surprised him.

“I thought probably they had peaked last week. Wrong. They went up again this week. So at least locally, we haven’t seen the peak yet. I would have expected this summer increase … to have plateaued and perhaps start to ease down. But we haven’t seen that yet,” he said.

Still, much of the country has moved on from the pandemic and is reacting to the surge with a collective shrug. COVID-19 is being treated like any other respiratory virus, including by the White House.

President Biden was infected in July. After isolating at home for several days and taking a course of the antiviral Paxlovid, he returned to campaign trial.

Biden is 81, meaning he’s considered high risk for severe infection. He received an updated coronavirus vaccine in September, but it’s not clear if he got a second one, which the CDC recommends for older Americans.

Updated vaccines that target the current variants are expected to be rolled out later this fall, and the CDC recommends everyone ages 6 months and older should receive one.

As of May, only 22.5 percent of adults in the United States reported having received the updated 2023-2024 vaccine that was released last fall and tailored to the XBB variant dominant at that time.

The immunity from older vaccines wanes over time, and while it doesn’t mean people are totally unprotected, Schaffner said, the most vulnerable should be cautious. Many people being infected now have significantly reduced immunity to the current mutated virus, but reduced immunity is better than no immunity.

People with healthy immune systems and who have previously been vaccinated or infected are still less likely to experience the more severe infections that result in hospitalization or death.

Almost “none of us are naive to COVID, but the people where the protection wanes the most are the most frail, the immunodeficient, the people with chronic underlying illnesses,” Schaffner said.