Fauci vs. Rogan: White House works to stomp out misinformation

The Biden administration is working to stamp out misinformation that might dissuade people from getting coronavirus shots, a crucial task as the nation shifts into the next, more difficult phase of its vaccination campaign.

The White House announced Friday that 100 million Americans are now fully vaccinated against COVID-19, but the nationwide rollout is plateauing as fewer people sign up for shots.

Administration officials and health experts know the difficulty ahead in getting vaccines into as many people as possible, and are trying to eliminate the barriers to doing so.

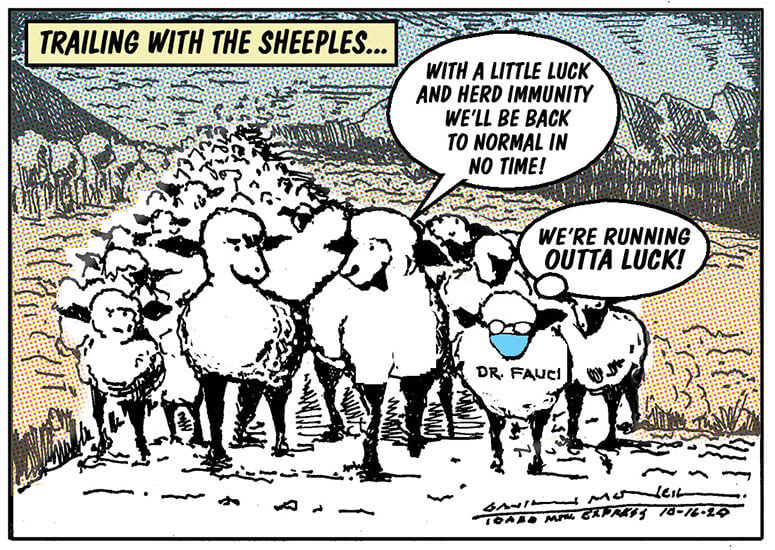

Authorities need to dispel the legitimate concerns that make people hesitant, while also stopping waves of misinformation.

This past week, top infectious diseases expert Anthony Fauci corrected Joe Rogan, a popular podcast host who himself later acknowledged his lack of medical knowledge, after Rogan said young healthy people don’t need to be vaccinated.

“You’re talking about yourself in a vacuum,” Fauci said of the podcast host. “You’re worried about yourself getting infected and the likelihood that you’re not going to get any symptoms. But you can get infected, and will get infected, if you put yourself at risk.”

White House communications director Kate Bedingfield also joined in the criticism.

“Did Joe Rogan become a medical doctor while we weren’t looking? I’m not sure that taking scientific and medical advice from Joe Rogan is perhaps the most productive way for people to get their information,” she told CNN.

Rogan’s comments were trending on Twitter for two days before he attempted to walk them back.

“I’m not a doctor, I’m a f—ing moron, and I’m a cage fighting commentator … I’m not a respected source of information, even for me,” he said.

Public health experts said Rogan’s comments were irresponsible, and potentially dangerous because they could perpetuate hesitancy.

“You have a responsibility as an adult, you have a responsibility as a community leader, your responsibility as a communicator to get it right,” said Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association.

While Rogan is not a political figure, he has one of the most popular podcasts in the world, and an enormous platform.

Rogan hosts the most popular podcast on Spotify. Rogan said in 2019 that his podcast was being downloaded 190 million times per month.

People are not getting all their information from Rogan, but when his comments clash with what public health experts say, that is problematic.

“It’s not so much that Joe Rogan’s a comedian, he’s very popular with people sort of leaning on the conservative side, especially young people. And that’s the group that we have to reach, especially young men,” said Peter Hotez, a leading coronavirus vaccinologist and dean of Baylor University’s National School of Tropical Medicine.

Hotez, who has appeared on Rogan’s show in the past, said he thinks the host was just misinformed. Hotez said he has reached out, and wants to help Rogan have a more productive discussion about why it’s so important for everyone to be vaccinated against the coronavirus.

Polls show vaccine hesitancy is declining, but the holdouts are not monolithic, and experts believe trusted messengers will be needed.

“I just think they have to speak the facts. You speak the facts, and anytime you discover the facts that are incorrect, you try to correct them,” said Benjamin. “And … I don’t think you demonize the individual, nor do I think you try to pin motive to it, because you don’t know what the motive is.”

Some people are most worried about side effects, some are concerned about the safety of the vaccines and some people don’t think COVID-19 is a problem at all. There are also likely some people who will never be convinced, and try to sow confusion and distrust.

Biden administration officials are aware of the harmful impact of misinformation, but know they are walking a fine line between people who legitimately want more information and those who just want chaos.

“We know that people have questions for multiple reasons. Sometimes because there’s misinformation that they’ve encountered, sometimes because they’ve had a bad experience with the healthcare system and they’re wondering who to trust, and some people have just heard lots of different news as we continue to get updates on the vaccine, and they want to hear from someone they trust,” Surgeon General Vivek Murthy said during a White House briefing.

For the White House, using medical experts like Fauci to correct obvious misinformation is part of the strategy to boost vaccine confidence.

“Our approach is to provide, and flood the zone with accurate information,” White House press secretary Jen Psaki said Friday. “Obviously that includes combating misinformation when it comes across.”

The administration has also invested $3 billion to support local health department programs and community-based organizations intended to increase vaccine access, acceptance and uptake.

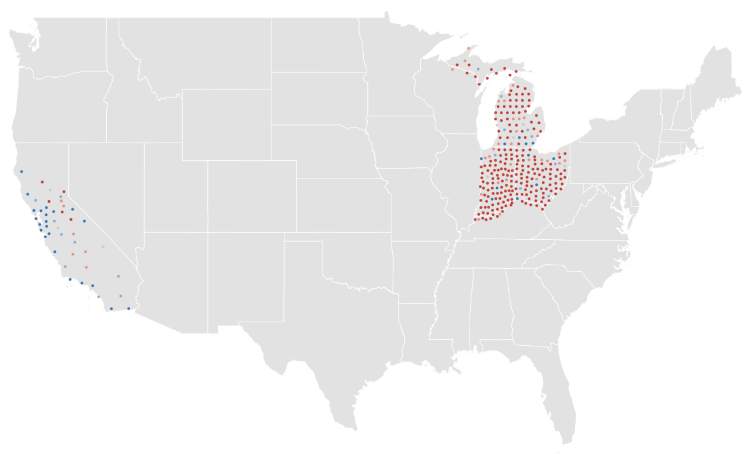

Still, experts said different messengers are needed, especially when trying to reach conservatives who may now view Fauci as a polarizing political figure.

“There needs to be a better organized effort by the administration to really understand how to reach groups that are identified in polls as saying they won’t get vaccinated,” Hotez said. “We need to figure out how to do the right kind of outreach with the conservative groups, and we’ve got to do something about” the damage caused by members of the conservative media.

In a recent CBS-YouGov poll, 30 percent of Republicans said they would not get the vaccine and another 19 percent said they only “maybe” would do so.

The underlying mistrust comes after a year in which Trump and his allies played down the severity of a virus that has killed more than half a million Americans already.

A national poll and focus group conducted by GOP pollster Frank Luntz showed Republicans who voted for President Trump will be far more influenced by their doctors and family members than any politician.

To that end, a group of Republican lawmakers who are also physicians released a video urging people to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

The video, led by Sen. Roger Marshall (R-Kan.), features some of the lawmakers wearing white coats with stethoscopes around their necks speaking into the camera.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18046968/web_1863137.jpg)