One hesitates to elevate obviously bad arguments, even to point out how bad they are. This is a conundrum that comes up a lot these days, as members of the media measure the utility of reporting on bad faith, disingenuous or simply bizarre claims.

If someone were to insist, for example, that they were not going to get the coronavirus vaccine solely to spite the political left, should that claim be elevated? Can we simply point out how deranged it is to refuse a vaccine that will almost certainly end an international pandemic simply because people with whom you disagree think that maybe this is a good route to end that pandemic? If someone were to write such a thing at some attention-thirsty website, we certainly wouldn’t want to link to it, leaving our own readers having to figure out where it might be found should they choose to do so.

In this case, it’s worth elevating this argument (which, to be clear, is actually floating out there) to point out one of the myriad ways in which the effort to vaccinate as many adults as possible has become interlaced with partisan politics. As the weeks pass and demand for the vaccine has tapered off, the gap between Democratic and Republican interest in being vaccinated seems to be widening — meaning that the end to the pandemic is likely to move that much further into the future.

Consider, for example, the rate of completed vaccinations by county, according to data compiled by CovidActNow. You can see a slight correlation between how a county voted in 2020 — the horizontal axis — and the density of completed vaccinations, shown on the vertical. There’s a greater density of completed vaccinations on the left side of the graph than on the right.

If we shift to the percentage of the population that’s received even one dose of the vaccine, the effect is much more obvious.

This is a relatively recent development. At the beginning of the month, the density of the population that had received only one dose resulted in a graph that looked much like the current density of completed doses.

If we animate those two graphs, the effect is obvious. In the past few weeks, the density of first doses has increased much faster in more-Democratic counties.

If we group the results of the 2020 presidential contest into 20-point buckets, the pattern is again obvious.

It’s not a new observation that Republicans are less willing to get the vaccine; we’ve reported on it repeatedly. What’s relatively new is how that hesitance is showing up in the actual vaccination data.

A Post-ABC News poll released on Monday showed that this response to the vaccine holds even when considering age groups. We’ve known for a while that older Americans, who are more at risk from the virus, have been more likely to seek the vaccine. But even among seniors, Republicans are significantly more hesitant to receive the vaccine than are Democrats.

This is a particularly dangerous example of partisanship. People 65 or older have made up 14 percent of coronavirus infections, according to federal data, but 81 percent of deaths. That’s among those for whom ages are known, a subset (though a large majority) of overall cases. While about 1.8 percent of that overall group has died, the figure for those aged 65 and over is above 10 percent.

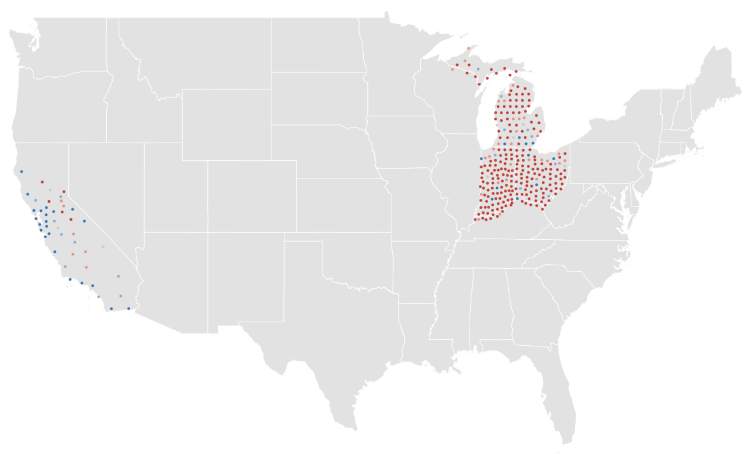

As vaccines have been rolled out across the country, you can see how more-heavily-blue counties have a higher density of vaccinations in many states.

This is not a universal truth, of course. Some heavily Republican counties have above-average vaccination rates. (About 40 percent of counties that preferred former president Donald Trump last year are above the average in the CovidActNow data. The rate among Democratic counties is closer to 80 percent.) But it is the case that there is a correlation between how a county voted and how many of its residents have been vaccinated. It is also the case that the gap between red and blue counties is widening.

Given all of that, it probably makes sense to point out that an argument against vaccines based on nothing more than “lol libs will hate this” is an embarrassing argument to make.