Cartoon – Recruiting an Aging Workforce

https://mailchi.mp/0b6c9295412a/the-weekly-gist-january-7-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

Every hospital in America has been affected by the growing shortage of nursing talent as the pandemic persists. This week a health system chief operating officer shared her greatest concern about the future of the nursing workforce: “We’re under immense pressure to find any nurses we can to keep units and operating rooms open. But if I think about the long-term impact, what I am most worried about is losing our most experienced nurses en masse.”

The average age of a nurse is 52, and 19 percent of nurses are over 65. Health systems have been facing a wave of retirements of Baby Boomer nurses, and the stresses of the pandemic, both in the workplace and at home, have dramatically accelerated the rate of tenured nurses leaving the profession, taking their well-honed clinical acumen with them.

“We’re looking at ways to increase the nursing pipeline, but you can’t replace a nurse with decades of experience one-to-one with someone just out of school, and expect the same level of clinical management, particularly for complex patients,” our COO colleague shared.

In the near term, her system is looking at two sets of strategies to maintain the nursing “brain trust”.

First, they hope to retain tenured nurses with job flexibility: “We’re not just losing nurses to retirement, we’re losing them to Siemens and Aetna—not because they are excited about that work, but because they don’t want to work a 12-hour shift. We have to be better about creating part-time, flexible schedules.”

Second, they are piloting telenursing and decision-support solutions to provide guidance and a second set of eyes for new nurses. These tools have also helped in new nurse recruitment. We’d predict the workforce crisis will persist far beyond the pandemic, and require rethinking of training, process automation, and the boundaries of practice license. But in the near-term, retaining and upskilling the talent we have is essential to maintaining access and quality.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/12/28/nursing-home-hospital-staff-shortages/

At the 390-bed Terrace View nursing home on the east side of Buffalo, 22 beds are shut down. There isn’t enough staff to care for a full house, safely or legally.

That means some fully recovered patients in the adjacent Erie County Medical Center must stay in their hospital rooms, waiting for a bed in the nursing home. Which means some patients in the emergency department, who should be admitted to the hospital, must stay there until a hospital bed opens up. The emergency department becomes stretched so thin that 10 to 20 percent of arrivals leave without seeing a caregiver — after an average wait of six to eight hours, according to the hospital’s data.

“We used to get upset when our ‘left without being seen’ went above 3 percent,” said Thomas Quatroche, president and chief executive of the Erie County Medical Center Corp., which runs the 590-bed public safety net hospital.

Nursing home bed and staff shortages were problems in the United States before the coronavirus pandemic. But the departure of 425,000 employees over the past two years has narrowed the bottleneck at nursing homes and other long-term care facilities at the same time that acute care hospitals are facing unending demand for services due to a persistent pandemic and staff shortages of their own.

With the omicron variant raising fears of even more hospitalizations, the problems faced by nursing homes are taking on even more importance. Several states have sent National Guard members to help with caregiving and other chores.

Hospitalizations, which peaked at higher than 142,000 in January, are rising again as well, reaching more than 71,000 nationally on Thursday, according to data tracked by The Washington Post. In some places, there is little room left in hospitals or ICUs.

About 58 percent of the nation’s 14,000 nursing homes are limiting admissions, according to a voluntary survey conducted by the American Health Care Association, which represents them. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 425,000 employees, many of them low-paid certified nursing assistants who are the backbone of the nursing home workforce, have left since February 2020.

“What we’re seeing on the hospital side is a reflection of that,” said Rob Shipp, vice president for population health and clinical affairs at the Hospital Association of Pennsylvania, which represents medical providers in that state. The backups are not just for traditional medical inpatients ready for follow-up care, he said, but psychiatric and other patients as well.

A handful of developmentally disabled patients at Erie County Medical Center waited as long as a year for placement in a group setting, Quatroche said. Medical patients recovered from illness and surgery who cannot go home safely may wait days or weeks for a bed, he said.

“I don’t know if everyone understands how serious the situation is,” Quatroche said. “You really don’t know until you need care. And then you know immediately.”

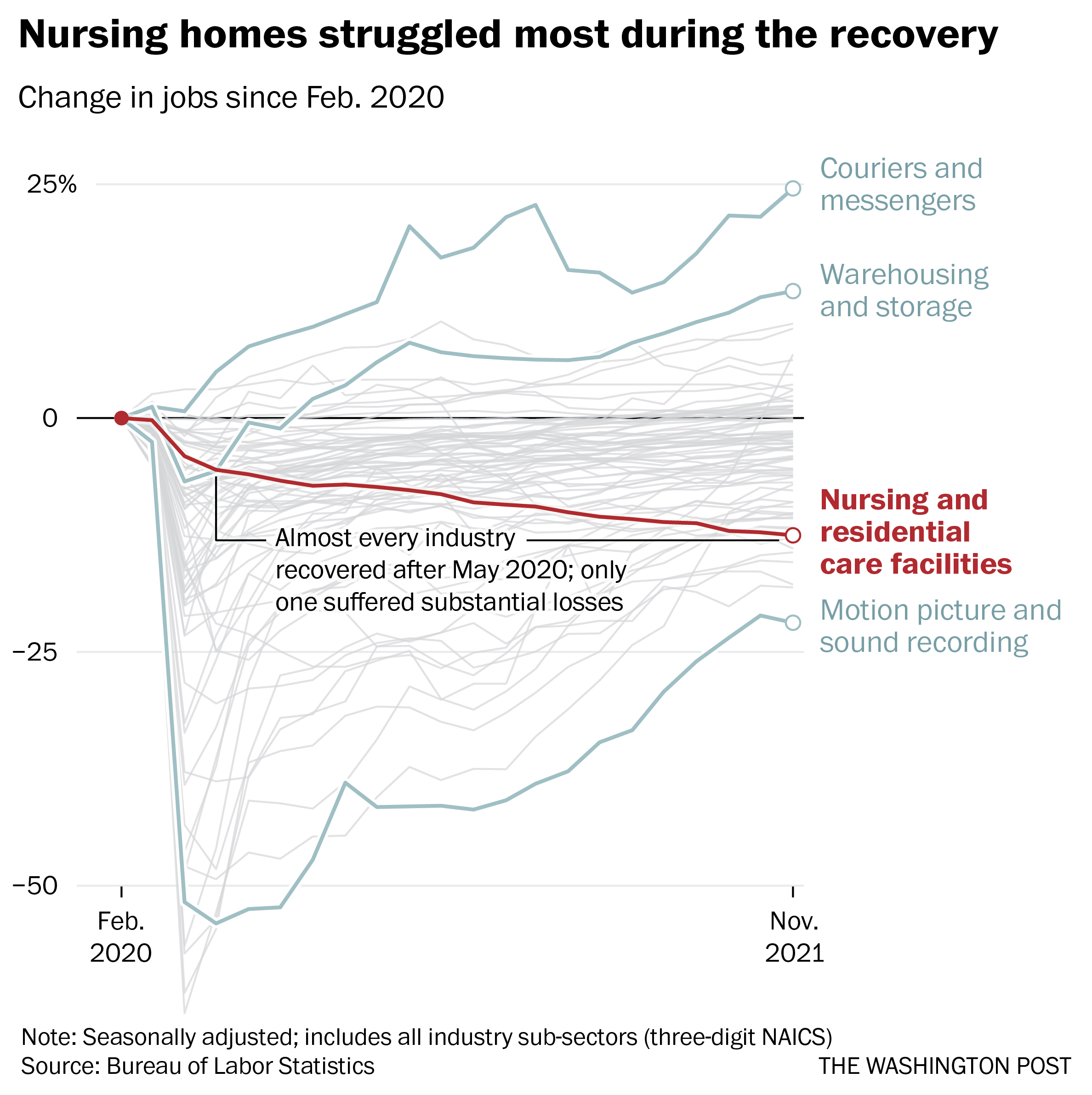

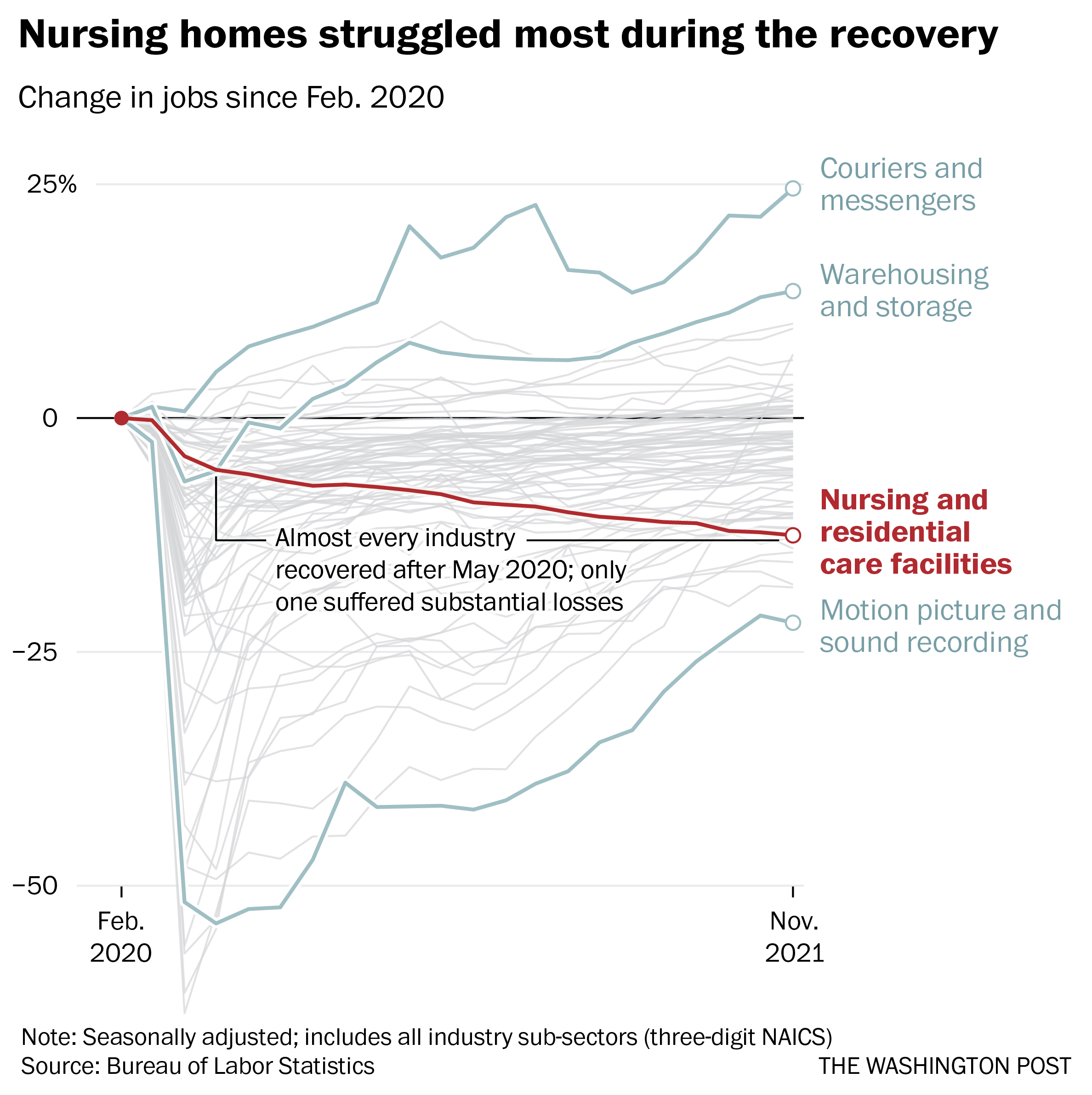

Remarkably, despite the horrific incidents of death and illness in nursing homes at the outset of the pandemic, more staff departures have come during the economic recovery. As restaurants and shops reopened and hiring set records, nursing homes continued to bleed workers, even as residents returned.

Nearly 237,000 workers left during the recovery, data through November show. No other industry suffered anything close to those losses over the same period, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Workers in the broader health-care industry have been quitting in record numbers for most of the pandemic, plagued by burnout, vulnerability to the coronavirus and poaching by competitors. Low-wage workers tend to quit at the highest rates, Labor Department data show, and nursing home workers are the lowest paid in the health sector, with nonmanagerial earnings averaging between $17.45 an hour for assisted living to $21.19 an hour for skilled nursing facilities, according to the BLS.

Nursing home occupancy fell sharply at the start of the pandemic, but inched back upward in 2021, according to the nonprofit National Investment Center for Seniors Housing and Care. One major force that held it back was worker shortages.

“Operators in the business have said we could admit more patients, but we cannot find the staff to allow that to happen,” said Bill Kauffman, senior principal at the organization.

Shortages have spawned fierce talent wars in the industry, Brookdale Senior Living Chief Executive Officer Cindy Baier said in a recent earnings call. When they don’t have enough workers, restaurants can reduce service hours and hospitals can cut elective surgeries, but nursing homes don’t have the option of eliminating critical services, she said. They must close beds.

“We are in the ‘people taking care of people’ business around-the-clock, 365 days a year,” she said.

Nursing homes tend to gain workers during a recession but can struggle to hire during expansions, according to an analysis of county-level data from the Great Recession recently published in the health care provision and financing journal Inquiry.

Steady income from their resident population and government programs such as Medicaid makes them recession-proof, and their low pay and challenging work conditions mean they’re chronically understaffed, said one of the study’s authors, Indiana University health-care economist Kosali Simon.

When recessions occur, nursing homes go on a hiring spree, filling holes in their staff with qualified workers laid off elsewhere.

“People during a recession may lose their construction jobs or jobs in retail sectors, and then look for entry-level positions at places like nursing homes where there is always demand,” Simon said.

Now, amid the “Great Resignation” and the hot job market, the opposite is happening. In sparsely populated areas and regions where pay is lower, the problem is even worse.

The Diakonos Group, which operates 26 nursing homes, assisted-living facilities and group homes in Oklahoma, closed an 84-bed location for seniors with mental health needs in May “simply because we couldn’t staff it any longer,” said Chief Executive Officer Scott Pilgrim. Patients were transferred elsewhere, including Tulsa and Oklahoma City, he said.

The home in rural Medford, which depended entirely on Medicaid payments, “was never easy to staff, but once we started through covid and everything, our staff was just burned out.”

Diakonos boosted certified nursing assistants’ pay from $12 an hour and licensed practical nurses’ pay from $20 an hour, used federal and state assistance to offer bonuses and employed overtime, but workers kept leaving for better health-care jobs and positions in other industries, he said.

“I’ve never been able to pay what we ought to pay,” Pilgrim said. Eventually he began to limit admissions and eventually was forced to close.

“The hospitals are backed up,” he said. “They’re trying to find anywhere to send people. We get referrals from states all around us. The hospitals are desperate to find places to send people.”

In south central Pennsylvania, SpiriTrust Lutheran is not filling 61 of its 344 beds in six facilities because of the worker shortage, said Carol Hess, the company’s senior vice president.

“I have nurses who went to become real estate agents,” she said. “They were just burned out.”

Pay raises of $1 to $1.50 an hour and bonuses brought the lowest-paid workers to about $15 an hour, Hess said, and the company is planning a recruiting drive after Jan. 1. But the prognosis is still grim.

“We’re competing with restaurants for our dining team members,” Hess said. “We’re competing with other folks for cleaning and laundry and others.” In the area around Harrisburg where SpiriTrust employees live, some schools that turned out certified nurse assistants closed during the pandemic and haven’t reopened.

The nursing homes have begun borrowing licensed practical nurses from WellSpan Health, the nearby hospital system that discharges many of its patients to SpriTrust after they recover. About 15 have began their orientations this month, she said, and the two systems are collaborating to pay them.

The bed shortage is causing backups that can average several days in the hospital, said Michael Seim, the hospital system’s chief quality officer. That gives the hospitals an interest in helping any way they can, he said.

“We have between 80 and 100 patients waiting for some type of skilled care,” Seim said this month. The hospital has begun caring for more people at home, enrolling 400 people so far in a program that sends clinicians to check on them there. More than 90 percent have said they are happy with the program.

“I think the future of hospital-based care is partnerships,” Seim said. “It’s going to be health systems partnering across their service areas … to disrupt the model we have.”

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/weekly-unemployment-claims-week-ended-dec-18-2021-232812196.html

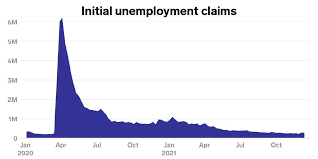

New weekly jobless claims held below pre-pandemic levels last week, further underscoring still-solid demand for labor heading into the new year.

The Labor Department released its latest weekly jobless claims report Thursday at 8:30 a.m. ET. Here were the main metrics from the print, compared to consensus estimates compiled by Bloomberg:

This week’s new jobless claims report coincides with the survey week for the December monthly jobs report from the Labor Department, offering an early indication of the relative strength expected in that print due for release in early January.

At 205,000, initial unemployment claims were expected to come in below even pre-pandemic levels yet again, with jobless claims having averaged around 220,000 per week throughout 2019. Earlier this month, first-time unemployment filings fell sharply to 188,000, or the lowest level since 1969. And based on the latest report, the four-week moving average for new claims was near its lowest in 52 years, ticking up by 2,750 week-over-week to reach 206,250.

Continuing claims have also come down sharply from pandemic-era highs, albeit while remaining slightly above the 2019 average of about 1.7 million. This metric, which counts the total number of individuals claiming benefits across regular state programs, came in below 2 million for a fourth straight week and reached the lowest level since March 2020.

“The claims data indicate strong demand for workers and a reluctance by businesses to lay off workers,” Rubeela Farooqi, chief economist for High Frequency Economics, wrote in a note. “However, disruptions around Omicron and Delta could be a headwind if businesses have to close for health-related reasons.”

“Overall, the direction in the labor market recovery remains positive, with demand still strong,” she added. “Labor shortages are persisting, preventing a stronger recovery, although these appeared to ease somewhat in November.”

And indeed, policymakers have also taken note of the improving labor market situation. In a press conference last week, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell maintained, “Amid improving labor market conditions and very strong demand for workers, the economy has been making rapid progress toward maximum employment.” And at the close of the Federal Open Market Committee’s latest policy-setting meeting, officials decided to speed their rate of asset-purchase tapering, paring back some crisis-era support in the economy as the recovery progressed.

Many Americans have also cited solid labor market conditions, especially as job openings hold at historically high levels. In the Conference Board’s latest Consumer Confidence report for December, 55.1% of consumers surveyed said jobs were “plentiful.” While this rate was down slightly from November’s 55.5%, it still represented a “historically strong reading,” according to the Conference Board.

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/weekly-unemployment-claims-week-ended-dec-4-2021-192034644.html

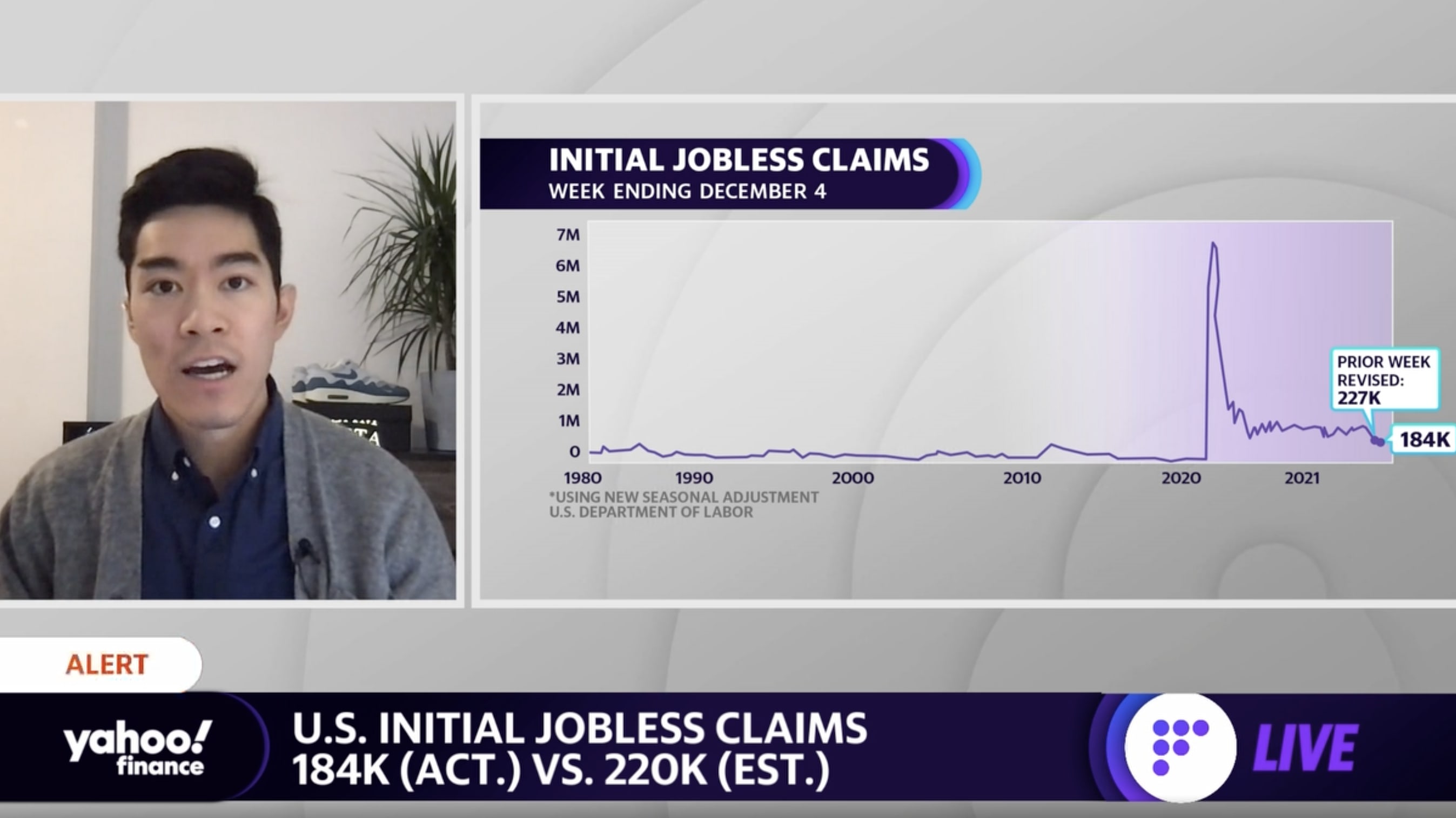

New initial jobless claims improved much more than expected last week to reach the lowest level in more than five decades, further pointing to the tightness of the present labor market as many employers seek to retain workers.

The Labor Department released its weekly jobless claims report on Thursday. Here were the main metrics from the print, compared to consensus estimates compiled by Bloomberg:

Jobless claims decreased once more after a brief tick higher in late November. At 184,000, initial jobless claims were at their lowest level since Sept. 1969.

“The consensus always looked a bit timid, in light of the behavior of unadjusted claims in the week after Thanksgiving in previous years when the holiday fell on the 25th, but the drop this time was much bigger than in those years, and bigger than implied by the recent trend,” Ian Shepherdson, chief economist for Pantheon Macroeconomics, wrote in an email Thursday morning. “A correction next week seems likely, but the trend in claims clearly is falling rapidly, reflecting the extreme tightness of the labor market and the rebound in GDP growth now underway.”

After more than a year-and-a-half of the COVID-19 pandemic in the U.S., jobless claims have begun to hover below even their pre-pandemic levels. New claims were averaging about 220,000 per week throughout 2019. At the height of the pandemic and stay-in-place restrictions, new claims had come in at more than 6.1 million during the week ended April 3, 2020.

Continuing claims, which track the number of those still receiving unemployment benefits via regular state programs, have also come down sharply from pandemic-era highs, and held below 2 million last week.

“Beyond weekly moves, the overall trend in filings remains downward and confirms that businesses facing labor shortages are holding onto workers,” wrote Rubeela Farooqi, chief U.S. economist for High Frequency Economics, in a note on Wednesday.

Farooqi added, however, that “the decline in layoffs is not translating into faster job growth on a consistent basis, which was evident in a modest gain in non-farm payrolls in November.”

“For now, labor supply remains constrained and will likely continue to see pandemic effects as the health backdrop and a lack of safe and affordable child care keeps people out of the workforce,” she added.

Other recent data on the labor market have also affirmed these lingering pressures. The November jobs report released from the Labor Department last Friday reflected a smaller number of jobs returned than expected last month, with payrolls growing by the least since December 2020 at just 210,000. And the labor force participation rate came in at 61.8%, still coming in markedly below its pre-pandemic February 2020 level of 63.3%.

And meanwhile, the Labor Department on Wednesday reported that job openings rose more than expected in October to top 11 million, coming in just marginally below July’s all-time high of nearly 11.1 million. The quits rate eased slightly to 2.8% from September’s record 3.0% rate.

“There is a massive shortage of labor out there in the country that couldn’t come at a worst time now that employers need workers like they have never needed them before. This is a permanent upward demand shift in the economy that won’t be alleviated by companies offering greater incentives to their new hires,” Chris Rupkey, FWDBONDS chief economist, wrote in a note Wednesday. “Wage inflation will continue to keep inflation running hot as businesses fall all over themselves in a bidding war for talent.”

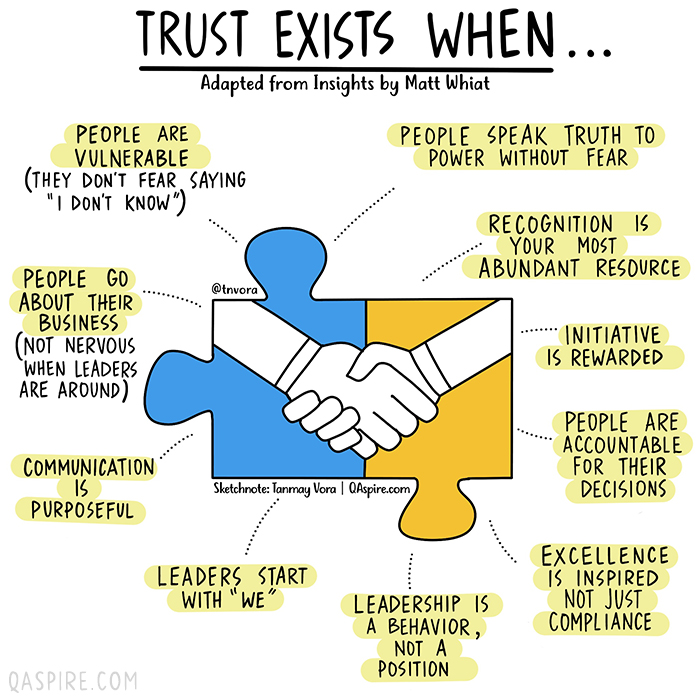

In the era of great awakening, leaders have to step up and be conscious about building trust with people they work with.

The old rules and hierarchies, that were already becoming obsolete, have now been thrown out of the window. People look for integration of work and well-being knowing that work is what you do, not a place you go to.

Opportunities are abound and excellent people have ample choices (they always had). It is high time that organizations and leaders think this through carefully to first align their own mindset to this new reality and then take conscious actions to build teams, practices and processes that are not just high-performing but also have a strong fabric of trust woven in.

Employees, after all, are volunteers who exercise their choice of working with you. Effective leadership is about making it worth for them.

Building high-trust environment means putting the human back at the center of how a business functions and building everything – purpose, culture, processes, structures, rituals, systems, tools and mindsets – around it.

How would we know if we are working in an environment where we can trust others and that we are trusted? We can always answer this based on our intrinsic feeling but if you are a leader who is working hard to build trust, here are a few vital signs that you need to look for.

PPE was in short supply early in the pandemic, spurring bidding wars and financially straining hospitals as they suffered from the budgetary fallout of canceled elective surgeries and other lucrative services.

While supply chain challenges have since eased and costs are down since their peak, hospitals are still spending more on PPE than before the pandemic, and consumption and demand remains strong in light of the delta variant, according to the report.

Premier used a database representing 30% of U.S. hospitals across all regions from September 2019 through last month to track spending trends, looking at costs for eye protection, surgical gowns, N95 respirators, face masks, exam gloves and swabs. It then calculated total costs measuring quantities used per patient, per day, multiplied by the percent change in pricing for the quarter.

Ultimately, hospitals are still using far more N95 respirators than they were prior to the pandemic.

Demand is still up for eye protection, surgical gowns and face masks, though pricing is close to pre-pandemic levels for those items. Costs for surgical gloves and N95 respirators are still above pre-pandemic levels, according to the analysis.

While most PPE costs have steadily declined for hospitals, other expenses have not, namely labor costs.

Contract labor costs have fluctuated, though they reached record highs amid COVID-19 surges, commanding record rates from providers. And nursing shortages, especially, have been so dire that hospitals are spending more on recruiting and retaining for the positions, boosting benefits and offering steep sign on bonuses.

Clinical labor costs are up 8% on average per patient, per day compared to before the pandemic, according to the earlier Premier analysis. That translates to about $17 million in additional annual labor expenses for the average 500-bed facility.

As of last month, overtime hours are up 52% since before the pandemic. The use of agency and temporary labor is up 132% for full-time employees and 131% for part-time employees.

The most expensive labor choices for hospitals are contract labor and overtime, typically adding 50% or more to an employee’s hourly rate, according to Premier.

For that report, Premier used a database with daily data from about 250 hospitals, bi-weekly data from 650 hospitals and quarterly data for 500 hospitals from October 2019 through August to analyze workforce trends among employees in emergency departments, intensive care units or nursing areas.