https://www.kaufmanhall.com/insights/thoughts-ken-kaufman/traditional-hospital-strategy-aging-out

On October 1, 1908, Ford produced the first Model T automobile. More than 60 years later, this affordable, mass produced, gasoline-powered car was still the top-selling automobile of all time. The Model T was geared to the broadest possible market, produced with the most efficient methods, and used the most modern technology—core elements of Ford’s business strategy and corporate DNA.

On April 25, 2018, almost 100 years later, Ford announced that it would stop making all U.S. internal-combustion sedans except the Mustang.

The world had changed. The Taurus, Fusion, and Fiesta were hardly exciting the imaginations of car-buyers. Ford no longer produced its U.S. cars efficiently enough to return a suitable profit. And the internal combustion technology was far from modern, with electronic vehicles widely seen as the future of automobiles.

Ford’s core strategy, and many of its accompanying products, had aged out. But not all was doom and gloom; Ford was doing big and profitable business in its line of pickups, SUVs, and -utility vehicles, led by the popular F-150.

It’s hard to imagine the level of strategic soul-searching and cultural angst that went into making the decision to stop producing the cars that had been the basis of Ford’s history. Yet, change was necessary for survival. At the time, Ford’s then-CEO Jim Hackett said, “We’re going to feed the healthy parts of our business and deal decisively with the areas that destroy value.”

So Ford took several bold steps designed to update—and in many ways upend—its strategy. The company got rid of large chunks of the portfolio that would not be relevant going forward, particularly internal combustion sedans. Ford also reorganized the company into separate divisions for electric and internal combustion vehicles. And Ford pivoted to the future by electrifying its fleet.

Ford did not fully abandon its existing strategies. Rather, it took what was relevant and successful, and added that to the future-focused pivot, placing the F-150 as the lead vehicle in its new electric fleet.

This need for strategic change happens to all large organizations. All organizations, including America’s hospitals and health systems, need to confront the fact that no strategic plan lasts forever.

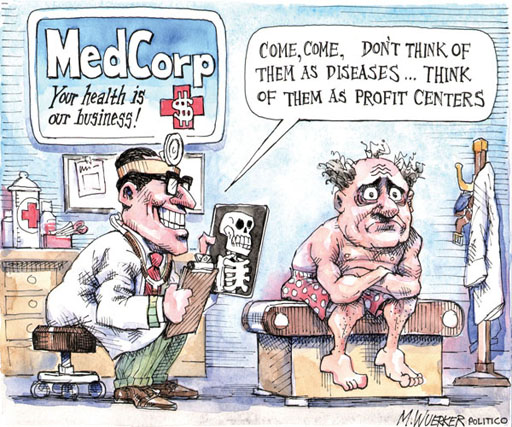

Over the past 25-30 years, America’s hospitals and health systems based their strategies on the provision of a high-quality clinical care, largely in inpatient settings. Over time, physicians and clinics were brought into the fold to strengthen referral channels, but the strategic focus remained on driving volume to higher-acuity services.

More recently, the longstanding traditional patient-physician-referral relationship began to change. A smarter, internet-savvy, and self-interested patient population was looking for different aspects of service in different situations. In some cases, patients’ priority was convenience. In other cases, their priority was affordability. In other cases, patients began going to great lengths to find the best doctors for high-end care regardless of geographic location. In other cases, patients wanted care as close as their phone.

Around the country, hospitals and health systems have seen these environmental changes and adjusted their strategies, but for the most part only incrementally. The strategic focus remains centered on clinical quality delivered on campus, while convenience, access, value, affordability, efficiency, and many virtual innovations remain on the strategic periphery.

Health system leaders need to ask themselves whether their long-time, traditional strategy is beginning to age out. And if so, what is the “Ford strategy” for America’s health systems?

The questions asked and answered by Ford in the past five years are highly relevant to health system strategic planning at a time of changing demand, economic and clinical uncertainty, and rapid innovation. For example, as you view your organization in its entirety, what must be preserved from the existing structure and operations, and what operations, costs, and strategies must leave? And which competencies and capabilities must be woven into a going-forward structure?

America’s hospitals and health systems have an extremely long history—in some cases, longer than Ford’s. With that history comes a natural tendency to stick with deeply entrenched strategies. Now is the time for health systems to ask themselves, what is our Ford F150? And how do we “electrify” our strategic plan going forward?