https://www.politifact.com/article/2020/nov/12/what-does-pfizers-covid-19-announcement-mean-you/

IF YOUR TIME IS SHORT

- If all goes according to plan, health care workers and individuals at high risk for severe illness from COVID-19 could be vaccinated as early as December.

- Experts predict that the broader public could start being vaccinated in April.

- The distribution of the vaccine could present some challenges for state and federal governments. That or any other unexpected events could delay the vaccine’s distribution.

When drugmaker Pfizer announced that its new vaccine was highly effective at preventing COVID-19, it raised hopes that the coronavirus pandemic could be nearing its end.

In a Nov. 9 press release, the company and its partner BioNTech claimed that an early analysis of clinical trial data found that inoculated individuals experienced 90% fewer cases of symptomatic COVID-19 than those who had received a placebo.

These results surpassed expectations. For months, experts have warned that a new vaccine might only be 60% effective. If Pfizer’s analysis is accurate — and it has yet to produce official scientific documentation — the new vaccine would offer a level of protection equal to that of highly effective vaccines for diseases such as measles.

Experts told us that Pfizer’s announcement is cause for optimism. However, the country, and the world, still have a way to go before coronavirus vaccines become available to ordinary Americans.

Here’s what we know about when the vaccine might be distributed and what that process could look like. What’s next for Pfizer’s vaccine?

If the information in the press release is accurate, Pfizer will likely be the first company to come up with a vaccine that meets the Food and Drug Administration’s requirements for distribution.

To get approval from the FDA, Pfizer has to gather two months of safety data on clinical trial participants to gauge whether the treatment has any negative side effects. The company will reach the two-month benchmark in the third week of November. Barring any unexpected developments, it will then submit its vaccine to the FDA for emergency use authorization, a special provision allowing the use of an unapproved product during a state of emergency.

After Pfizer submits its data to the FDA, the agency will analyze it to see if it’s sufficient to begin distribution. After approval from the FDA, the vaccine would be assessed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. The Advisory Committee will then issue a recommendation to the CDC, which will make the final ruling about whether to distribute the vaccine.

This might sound intricate, but James Blumenstock, the chief program officer for health security at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, said that the vaccine could probably be approved by the FDA and the CDC in a matter of days rather than weeks.

“Both agencies are standing ready and will give these requests and this assessment the highest level of priority just for expediency’s sake,” he said.

What this means is that high-priority Americans, such as health care workers, could be vaccinated as early as December. What a vaccine rollout might look like.

Pfizer predicts that it will be able to manufacture only 50 million doses for global consumption by the end of the year, enough to vaccinate 25 million people. (The world’s population is about 7.8 billion.)

With a limited number of doses available, the eventual rollout of a vaccine would likely consist of two phases. During the first phase, U.S. health care workers, emergency responders and individuals at higher risk of severe illness would be eligible for vaccination. If all goes according to plan, the first phase will commence sometime in December.

During the second phase, the vaccine would become available to the broader public. Most experts told us that they expect the second phase to start sometime in April, although the date would vary depending on Pfizer’s vaccine production rates and whether other companies get their vaccines greenlit by the FDA and CDC. The state of other vaccines

As of early July, there were roughly 160 vaccine projects under way worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

Pfizer’s announcement bodes well for other vaccine candidates, said Matthew B. Laurens, an associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health.

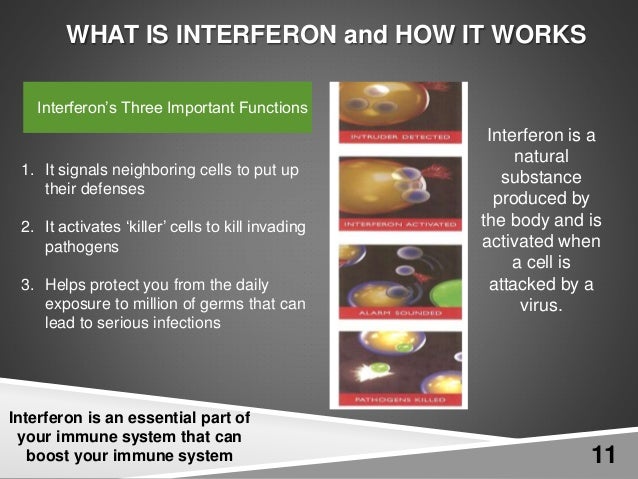

Pfizer’s vaccine uses genetic material, known as mRNA, that provides the instructions for a body to produce coronavirus proteins, known as antigens, in the hope that these could prime the human immune system to fight the virus. The biotechnology company Moderna is also manufacturing a vaccine that uses mRNA and is set to receive trial data by the end of November.

Other companies in the United States and Europe producing a vaccine include Novavax, which plans to start clinical trials in the U.S. and Mexico by the end of November; Johnson & Johnson, which recently resumed testing its vaccine candidate after a brief pause; and AstraZeneca, which expects to have clinical trial data by the end of the year.

The more companies there are that are able to produce a vaccine, the quicker the vaccine will become widely available, experts say.

Vaccine presents potential distribution hurdles

The CDC will be in charge of the distribution process, with involvement from the U.S. Defense Department, said Dr. Litjen Tan, chief strategy officer for the Immunization Action Coalition, which distributes information about vaccines to try to increase vaccination rates.

Vaccines would be manufactured and then transported to states, which will then pass the vaccine on to providers, such as hospitals. The McKesson Corp., which has received a federal contract to distribute the treatment, will assist pharmaceutical companies and the government with the shipping process.

Shipping the doses will present some challenges. Pfizer’s vaccine has complex and ultra-cold storage requirements that many hospitals, particularly those in hard-to-reach areas, won’t be able to meet.

The cold chain requirement “is an issue for Pfizer, but manufacturing and distribution are issues for all vaccines,” said Robert Finberg, a physician and infectious disease specialist at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center.

To surmount this hurdle, Pfizer plans to transport the vaccine in thermal shippers that can keep the vaccine at the necessary temperature of minus 70 degrees Celsius for about two weeks. However, the shippers themselves present additional problems for distribution, Tan said. Each shipment consists of five trays containing 975 doses of vaccine, and reducing the size of the shipment could dramatically raise the cost of distribution.

As a result, the states might initially prioritize shipping the vaccine to major hospitals rather than rural hospitals that service fewer patients in order to avoid waste.

Blumenstock told us that state and federal governments are working hard to make sure that all regions of the U.S. receive proportionate amounts of vaccine. However, he acknowledged that hospitals in remote areas that don’t service many patients could initially take longer to get the vaccine than a well-trafficked hospital in a heavily populated area.

“Outskirt hospitals won’t be ignored or marginalized, even if it takes more time and effort to get them the vaccine,” he said. “One of the primary principles will be equitable distribution, even when that means you need to take extraordinary measures for logistics, transportation, and handling.”

Overall, experts said that Pfizer’s announcement is a significant step forward. “I’m optimistic that we have a vaccine that’s safe and effective,” said Tan. “And I’m glad that what we’re dealing with now is the problem of how to get it to the public.”