In chaos theory, there’s a concept known as the butterfly effect—the idea that a seemingly small action, occurring at just the right moment, can trigger ripple effects that grow across time and space. A butterfly flaps its wings in Brazil, the saying goes, and a tornado forms weeks later in Texas.

Presidential decisions can carry the same weight, especially those made in the first 100 days of a new administration. Time and again, these early choices unleash far-reaching consequences that reshape a nation.

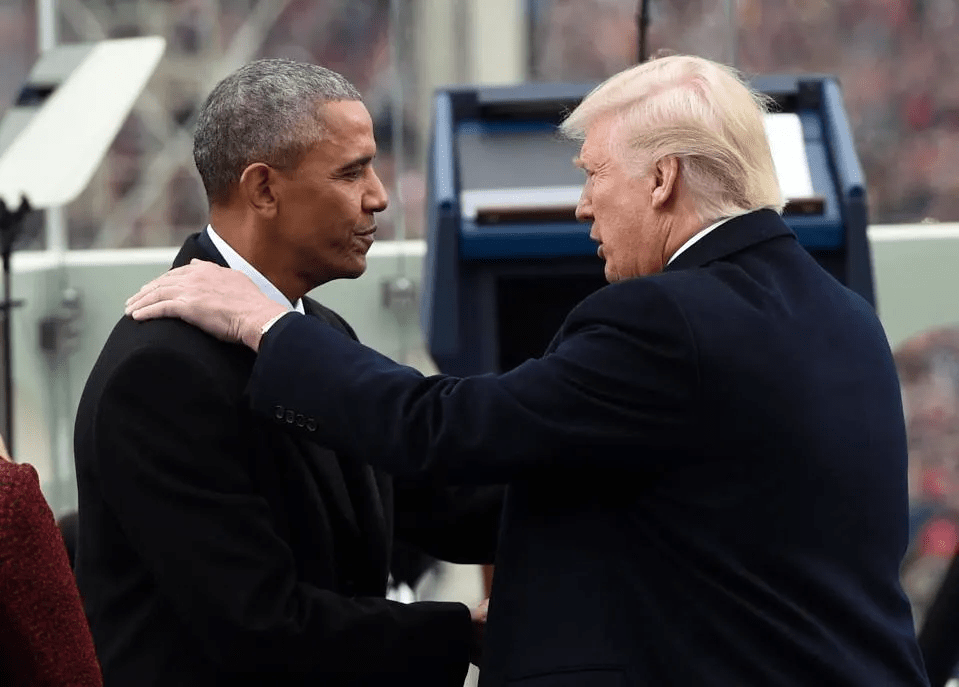

As Donald Trump wraps up the opening stretch of his second term, his healthcare-focused executive actions underscore the consequentiality of this early window. And when compared with Barack Obama’s approach in 2009 (the last time a president pursued major healthcare reforms right out of the gate), the contrast becomes even more striking.

Two presidents. Two defining moments. And one fundamental question that both men had to answer in the first 100 days: Where should healthcare reform begin — by expanding coverage, improving quality or cutting costs?

Crisis, Control And A Key Healthcare Choice

The idea that a president’s first 100 days matter dates back to Franklin D. Roosevelt. In 1933, during the depths of the Great Depression, FDR passed a wave of New Deal reforms that redefined the role of government in American life.

Ever since, the opening months of a new presidency have served as both proving ground and preview. They reveal how a president intends to govern and what he values most.

For both presidents Obama and Trump, their answer to the healthcare question — where to begin? — would shape what followed. Obama chose to expand coverage. Trump has chosen to cut costs. Those decisions set them on opposing paths. And with every subsequent policy decision, the gap between their contrasting approaches only grows.

’09 Obama: Health Coverage And Congressional Action

In the quiet calculus of early governance, President Obama concluded that without health insurance coverage, access to high-quality medical care would remain out of reach for tens of millions of Americans.

Confronting a system that left 60 million uninsured, he believed that expanding access to coverage was a vital first step — not only to improve individual health outcomes, but to create a healthier nation that ultimately would require less medical care (and spending) overall.

That belief was grounded in lived experience: his mother’s battle with cancer and the insurance disputes that followed, as well as his years as a community organizer working with families who couldn’t afford medical care.

He also understood that only Congressional legislation — rather than executive action — would make those gains durable. So, in his first 100 days, he pursued a strategy grounded in consensus-building. He convened healthcare stakeholders, hosted public healthcare summits, expanded the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) and proposed a federal budget that included a $634 billion “down payment” on healthcare reform.

’25 Trump: Cost Cutting And Executive Control

Donald Trump didn’t ease into his second term. He charged in, pen in hand. His priorities for the country were clear: cut taxes, impose tariffs and reduce federal spending.

For Trump, speed was of the essence. So, he bypassed Congress in favor of executive orders, downsizing healthcare agencies and dismantling regulatory oversight wherever possible.

At the center of Trump’s domestic agenda is an ambitious income tax overhaul, dubbed the “big beautiful bill.” But passing it will require support from fiscal conservatives in his own party. To offset the steep drop in tax revenue, Trump has signaled a willingness to slash federal spending, starting with healthcare programs.

What Comes Next: Mapping Health Policy Consequences

Presidents make thousands of decisions over the course of a four-year term, but those made in the first few months typically matter most. Both Obama and Trump had to decide whether to prioritize expanding coverage or cutting costs, and that choice would shape the steps that follow.

For Obama, the consequences of his choice were sweeping. His early focus on increasing health insurance coverage laid the foundation for the Affordable Care Act, the most ambitious healthcare reform since Medicare and Medicaid in the 1960s. The ACA provided affordable insurance to more than 30 million Americans, offered subsidies to low- and middle-income families, cut the uninsured rate in half and guaranteed protections for those with preexisting conditions. The law survived political opposition, legal challenges and subsequent presidencies.

However, those gains came at a price. Annual U.S. healthcare spending more than doubled — from $2.6 trillion in 2010 to over $5.2 trillion today — without significant improvements in life expectancy or care quality.

Trump’s early decisions are reshaping healthcare, too, but in ways that reflect a very different set of priorities and a sharply contrasting vision for the federal government’s role.

1. Cost-Driven Actions: Reducing Government Healthcare Spending

Guided by a business-oriented focus on cost containment, Trump has sought to reduce the federal government’s role in healthcare through sweeping budget and staffing changes. Among the most significant:

- Agency layoffs: The Department of Health and Human Services has initiated mass layoffs across the CDC, NIH and FDA, reducing staff capacity by 20,000 and cutting critical programs, including HIV research grants and initiatives targeting autism, chronic disease, teen pregnancy and substance abuse.

- ACA support rollbacks: The administration slashed funding for ACA navigators and rescinded extended enrollment periods, making it more difficult for individuals (especially low-income Americans) to obtain coverage.

- Planned Parenthood and family planning cuts: Freezing Title X funds has reduced access to reproductive healthcare in multiple states.

- Medicaid at risk: A proposed $880 billion reduction over 10 years could eliminate expanded Medicaid coverage in many states. Additional moves (like work requirements or application hurdles) would likely reduce enrollment further.

2. Cultural And Executive Power Moves: Redefining Government’s Role In Health

While cutting costs has been the central goal, many of Trump’s actions reflect a broader ideological stance. He’s using executive authority to reshape the values, norms and institutions that have defined American healthcare. These include:

- Withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO): The administration formally ended U.S. participation, citing concerns about funding and governance.

- Restructuring USAID’s health portfolio: Multiple contracts and programs related to maternal health, infectious disease prevention and international public health have been ended or scaled back.

- Policy changes on federal language and research topics: Executive directives have modified how agencies are allowed to address topics related to gender and sexuality, leading to the removal of LGBTQ+ content from health resources and websites.

- Reorganization of DEI programs: Diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives have been rolled back or eliminated across several federal departments.

The Likely Consequences Of Trump’s First 100 Days

President Trump’s early actions reveal two defining trends: cutting government healthcare spending and reshaping federal priorities through executive authority. Both are already changing how care is accessed, funded and delivered. And both are likely to produce lasting consequences.

The most immediate impact will come from efforts to reduce healthcare spending. Cuts to Medicaid, ACA enrollment support and family planning programs are expected to lower insurance enrollment, particularly among low-income families, young adults and people with chronic illness.

As coverage declines, care becomes harder to access and more expensive when it’s needed. The results: delayed diagnoses, avoidable complications and rising levels of uncompensated care.

His second set of actions — including reduced investment in federal science agencies — will slow drug development and weaken the infrastructure needed to respond to future public health threats.

Meanwhile, a more constrained and domestically focused healthcare agenda is likely to diminish trust in federal health agencies, limit access to culturally competent care and produce a loss of global leadership in health innovation.

The U.S. Constitution gives presidents broad power to chart the nation’s course. And the decisions made in their first 100 days shape the trajectory of an entire presidency.

One president decided to prioritize coverage, while a second chose cost-cutting. And like the flap of a butterfly’s wings, these early actions generate ripples — expanding in size over time and radically altering American healthcare, for better or worse.