Cartoon – Sorry, but there aren’t enough Life Jackets to go around

https://www.axios.com/coronavirus-west-virginia-first-case-ac32ce6d-5523-4310-a219-7d1d1dcb6b44.html

Former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb said on Sunday that despite widespread mitigation efforts, the coronavirus has exhibited “persistent spread” that could mean a “new normal” of 30,000 new cases and over 1,000 deaths a day through the summer.

The big picture: COVID-19 has killed over 66,000 Americans and infected over 1.1 million others in less than three months since the first known death in the U.S., Johns Hopkins data shows.

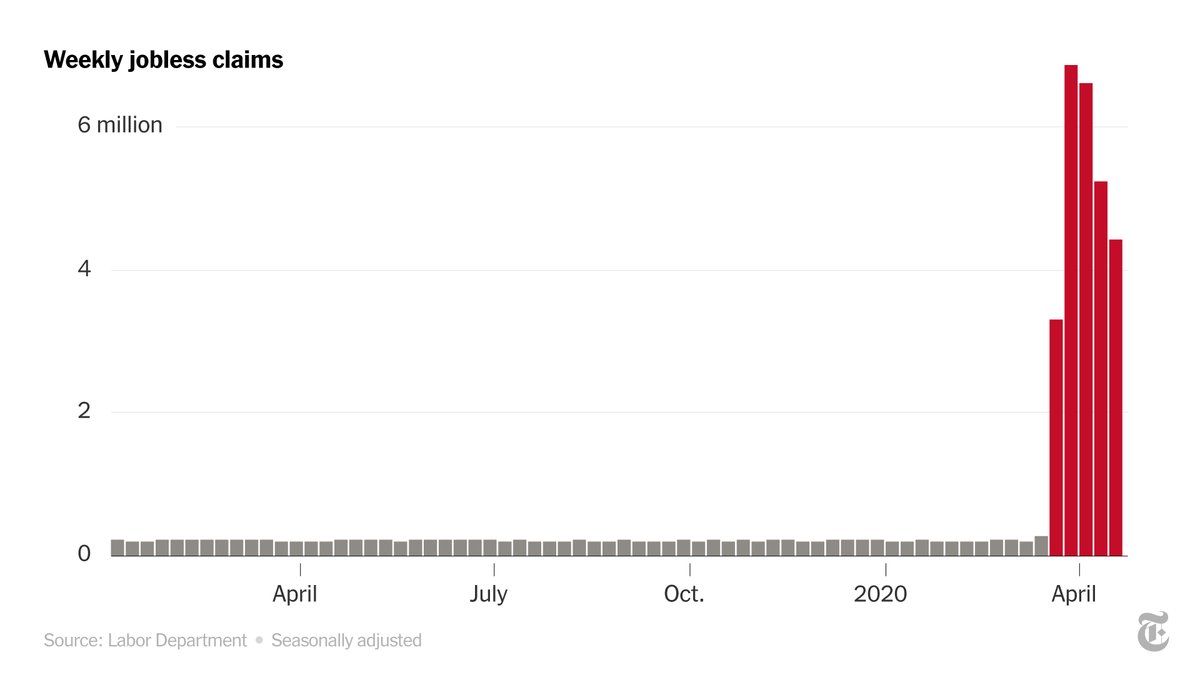

By the numbers: As states try to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus while easing restrictions, unemployment filings in the U.S. topped 30 million in six weeks, and the number of unemployed could be higher than the weekly figures suggest.

Catch up quick: The number of deaths in states hit hardest by the coronavirus is well above the normal range, according the CDC.

Lockdown measures: Dozens of states have outlined plans to ease coronavirus restrictions, but the pandemic’s impact on our daily lives, politics, cities and health care will outlast stay-at-home orders.

As the novel coronavirus pandemic brought business to a halt, the pain rippled outward, blowing up sector after sector. According to a detailed analysis of unemployment claims, no industry was left untouched.

After that first chaotic week of lockdowns mid-March, as officials scrambled to slow the spread of the deadliest pandemic in more than a century, restaurants and theaters saw job losses slow while losses in other sectors, such as construction and supply-chain work, accelerated. Now, it appears the economic upheaval is hitting professional and public-sector jobs that some once regarded as safe.

The Labor Department doesn’t release jobless claims by industry. So, building on the work of economist Ben Zipperer and his colleagues at the Economic Policy Institute, we analyzed industry-specific new unemployment-benefit claims from 14 states that publish them. (For a full list, see the charts below.)

For that, we need to focus in on the weekly changes in jobless claims to distinguish between industries where claims are falling and those where claims are steady or increasing. The data can also help us estimate how the labor market will change in coming months.

(Highest week-to-week change included: accommodation and food services; arts entertainment and recreation; hairdressers, auto mechanics and laundry workers)

The first week of closures slammed headfirst into industries that require the most face-to-face customer contact — America’s hospitality sector. More than 7 percent of all restaurant, hotel and bar workers filed for unemployment in this first week alone.

For public officials looking to enforce social distancing, bars, hotels and movie theaters were obvious targets: They’re discretionary spending and require significant human interaction. Another category, which the government calls “other services” but is primarily made up of hairdressers, auto mechanics and laundry workers, also suffered swift and significant losses.

The number of newly unemployed filers in all these high-contact industries fell off in subsequent weeks, but they remain the biggest casualties of the crisis. And unemployment claims probably understate the pain of lower-earning Americans. Low-wage workers often don’t qualify for benefits because they haven’t spent enough time on the job, or aren’t being paid enough, Zipperer said.

A survey released Tuesday by Zipperer and his colleague Elise Gould implies unemployment numbers may be significantly worse than government statistics show. For every 10 people who successfully applied for unemployment benefits during the crisis, they show, another three or four couldn’t get through the overloaded system, and two more didn’t even apply because the system is too difficult.

(Highest week-to-week change included: manufacturing; construction; retail)

By the second week, the shutdown moved from businesses where the primary danger is interacting with customers to those, like construction and manufacturing, that require in-person interaction with large crews of colleagues.

On March 26, for example, Spokane, Wash.-area custom-cabinet maker Huntwood Industries, laid off around 500 employees, according to Thomas Clouse of the Spokesman-Review. As a manufacturer whose sales depend on the construction industry, it was hit doubly hard by the shutdowns.

“It is a scary time,” Amy Ohms, 37, told Clouse. “It’s kind of unfair. I think construction is essential. There is a lot of uncertainty.”

Manufacturers were among the first publicly traded companies to note travel and supply-chain risks related to the coronavirus outbreak in China in financial filings, according to a separate analysis by Oxford researchers Fabian Stephany and Fabian Braesemann and collaborators in Berlin. By March, manufacturers were noting domestic production issues.

Their analysis also shows that, in the middle of March, concern about the coronavirus and its disease, covid-19, from retail corporations eclipsed that of manufacturers. Indeed, retail struggled mightily in the second week of the crisis. More workers were told to stay home, and folks realized foot traffic was often incompatible with social distancing.

The retail sector wasn’t hit as quickly or as forcefully as food services or entertainment, presumably because the sector includes grocery stores and others who employ workers who were deemed essential.

(Highest week-to-week change included: wholesale trade; retail trade; administrative and waste management)

In the third week, the pain worked its way up the supply chain, as wholesale trade — a sector that includes some sales representatives, truck drivers and freight laborers — got slammed.

In theory, the lockdowns created near-perfect trucking conditions: traffic vanished, diesel keeps getting cheaper and the roads are safer than they have been in decades. Only one problem: There’s not much to haul right now.

Don Hayden, president of Louisville trucking firm M&M Cartage, feared he would have to lay off about 70 percent of his 400 employees — drivers, mechanics and office staff — in early April. Orders from his customers in heavy manufacturing evaporated.

But, just in time, he got a Payroll Protection Program loan through his local bank. He was shocked at how rapidly his loan was approved and the money arrived, and he said the Treasury Department had done an outstanding job.

“We’re good through May and into June,” he said. “We have a good workforce. We’re proud of them. We sure would like to retain them.”

At this point in the crisis, the focus shifted from huge, industry-eviscerating swings in jobless numbers to gradual weekly trends that help us guess where the jobless claims will settle in the weeks and months to come.

As industries fall like dominoes, policymakers need to realize the damage isn’t contained to a few specific sectors, said University of Tennessee economist Marianne Wanamaker, a former member of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers.

She said there may be a temptation to extend benefits for difficult-to-reopen industries such as food service and hospitality, but “it doesn’t comport with the data because the damage is so widespread. It’s not fair to say, ‘Hotel and restaurant workers, you get these really generous packages and everybody else has to go back to work.’ ”

(Highest week-to-week change included: management; finance and insurance; public administration)

White-collar industries have been shedding jobs since mid-March, albeit at a much lower rate than lower-income sectors. But as losses in low-income sectors subsided, white-collar jobless claims stayed flat or even intensified. By week four, categories that contain managers, bookkeepers, insurance agents and bank tellers saw some of the worst weekly trends of any sector.

On April 9, the online review site Yelp laid off 1,000 workers and furloughed 1,100 more (about a third of its workforce) as traffic on the site plunged while businesses were locked down.

“The physical distancing measures and shelter-in-place orders, while critical to flatten the curve, have dealt a devastating blow to the local businesses that are core to our mission,” CEO Jeremy Stoppelman wrote at the time.

Jane Oates, president of the employment-focused nonprofit organization WorkingNation, used to oversee the Labor Department wing that coordinates unemployment claims and training. “The big difference between coronavirus and the Great Recession is that this has completely stopped the economy across so many sectors,” she said.

During the Great Recession, she and her team had the luxury of flooding support into areas that were being hit hardest in a particular week or month. They went from state to state and industry to industry, putting out fires as they arose.

The Labor Department can’t address individual problems like that during the coronavirus recession, she said, because everybody’s getting shellacked simultaneously.

(Highest week-to-week change included: oil, gas and mining; utilities; public administration)

In the week ending April 18, the most recent for which we have data, we can no longer avoid one of the most ominous trends in the entire analysis: a rise in public-sector layoffs. Utilities, public administration and education services — all of which have close implicit or explicit ties to state and local government, were among the worst-faring sectors on a weekly basis.

To stem the tide of what could be millions of job losses and furloughs, the National League of Cities is pushing for a $250 billion bailout of cities throughout the country, colleague Tony Romm reports.

In Broomfield, Colo., a Denver-area suburb of about 70,000 residents, 235 city and county employees were furloughed on April 22, according to Jennifer Rios in the Broomfield Enterprise.

“The impact of the COVID-19 coronavirus is more significant than any of us could have ever expected for our well-being, as well as our municipal financial stability,” Rios reports that officials wrote in a letter to furloughed employees.“

State and local governments are typically required to balance their budgets. Now that they’re staring down the barrel of a huge tax-revenue shortfall, “these revenue losses are going to cause government budgets to fall and they’re going to lay people off,” Zipperer said.

“You’re seeing the beginnings of a big contraction in the public sector,” he said. “That’s going to be the next huge thing.”

The public sector used to be the bulwark that kept the economy going while the private sector pulled back during a recession, Zipperer said. “Over the last couple of recessions, the public sector hasn’t played that traditional role,” Zipperer said. “As a result, we’ve seen steeper recessions and slower recoveries.”

On the heels of worse-than-anticipated first-quarter GDP data, investors got additional economic data Thursday to reflect the ongoing damage being done to the U.S. economy as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The U.S. Labor Department released its weekly jobless claims figures Thursday morning, and another 3.839 million Americans filed for unemployment benefits during the week ending April 25. Economists were predicting 3.5 million claims for the week, and the prior week’s figure was revised higher to 4.44 million from 4.43 million. In just the previous six weeks, more than 30 million Americans have filed unemployment insurance claims.

Continuing claims, which lags initial jobless claims data by one week, totaled 17.99 million for the week ending April 18. The prior week’s record 15.98 million continuing claims was revised lower to 15.82 million.

“This is the fourth consecutive slowing in the pace of new jobless claims, but it is still horrible and underlines the severe economic consequences of the Covid-19 containment measures,” ING economist James Knightley wrote in a note Thursday.

“The re-opening of some states, including Georgia, Tennessee, South Carolina and Florida, appear to have gone fairly slowly. Consumers remain reluctant to go shopping or visit a restaurant due to lingering COVID-19 fears, while the social distancing restrictions placed on the number of customers allowed in restaurants do not make it economically justifiable for some to open. Evidence so far suggests very little chance of a V-shaped recovery, meaning that unemployment is unlikely to come down anywhere near as quickly as it has been going up,” Knightley added.

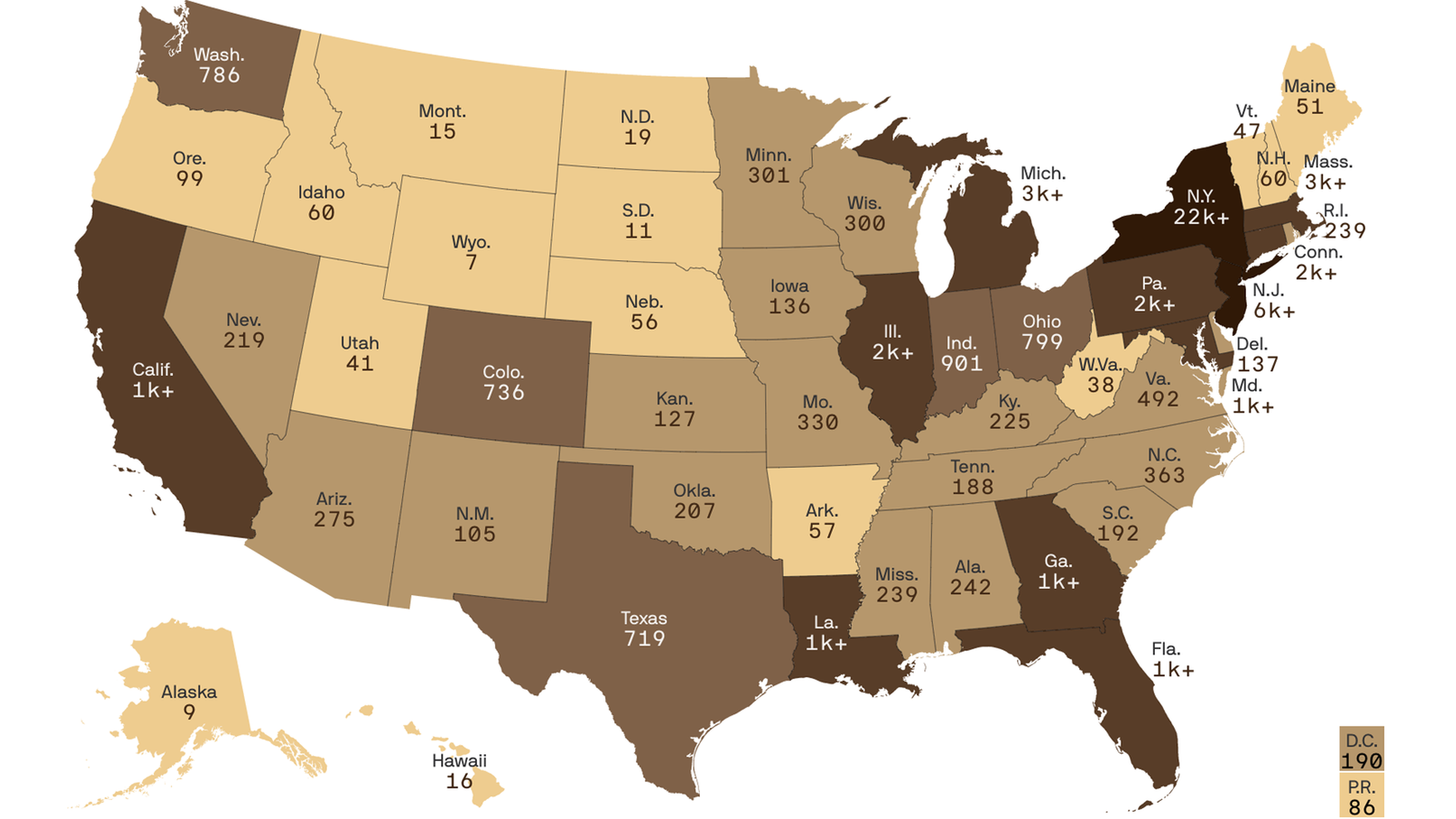

Certain states got hit harder than others last week as massive backlogs continued to pile up, and states that implemented shelter-in-place orders later than others saw an increase in claims. For the week ending April 25, Florida saw the highest number of initial jobless claims at an estimated 432,000 on an unadjusted basis, from 507,000 in the prior week. California reported 328,000, down from 528,000 in the previous week. Georgia had an estimated 265,000 and Texas reported 254,000.

While consensus economists anticipate weekly jobless claims will be in the millions in the near term, a continued steady decline is largely expected going forward.

“We expect initial jobless claims to continue to decline on a weekly basis. Many workers affected by closures of nonessential businesses have likely already filed for benefits at this point,” Nomura economist Lewis Alexander wrote in a note April 27. “In addition, the strong demand for Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, part of the CARES Act passed on 27 March, suggests some room for labor market stabilization.”

However, Barclays warned that some recent data indicated that the decline in weekly claims could actually be slower than previously estimated.

“NYC 311 calls in the week ending April 24 were running about 30% higher than a week earlier and support our change in forecast,” Barclays economist Blerina Uruci wrote in a note Wednesday. “In particular, we find it concerning that after declining steadily in recent weeks, the number of calls related to unemployment rose again during the week ending April 24.”

The firm increased its estimate for weekly jobless claims to 4 million from the previously estimated 3.25 million for the week ending April 25. Bank of America also boosted its estimate for claims to 4.1 million from the previously forecast 3.5 million claims.

“Scanning through the local news, we were able to locate information about ten states + DC. We found that claims declined only 2.5% week-to-week NSA [not seasonally adjusted],” Bank of America said in a note Wednesday.

COVID-19 cases recently topped 3.2 million worldwide, according to Johns Hopkins University data. There were more than 1 million cases in the U.S. and 60,000 deaths, as of Thursday morning.

https://www.axios.com/coronavirus-west-virginia-first-case-ac32ce6d-5523-4310-a219-7d1d1dcb6b44.html

The pandemic is a long way from over, and its impact on our daily lives, information ecosystem, politics, cities and health care will last even longer.

The big picture: The novel coronavirus has infected more than 939,000 people and killed over 54,000 in the U.S., Johns Hopkins data shows. More than 105,000 Americans have recovered from the virus as of Sunday.

Lockdown measures: Demonstrators gathered in Florida, Texas and Louisiana Saturday to protest stay-at-home orders designed to protect against the spread of COVID-19, following a week of similar rallies across the U.S.

Catch up quick: Deborah Birx said Sunday that it “bothers” her that the news cycle is still focused on Trump’s comments about disinfectants possibly treating coronavirus, arguing that “we’re missing the bigger pieces” about how Americans can defeat the virus.

With 4.4 million added last week, the five-week total passed 26 million. The struggle by states to field claims has hampered economic recovery.

Nearly a month after Washington rushed through an emergency package to aid jobless Americans, millions of laid-off workers have still not been able to apply for those benefits — let alone receive them — because of overwhelmed state unemployment systems.

Across the country, states have frantically scrambled to handle a flood of applications and apply a new set of federal rules even as more and more people line up for help. On Thursday, the Labor Department reported that another 4.4 million people filed initial unemployment claims last week, bringing the five-week total to more than 26 million.

“At all levels, it’s eye-watering numbers,” Torsten Slok, chief international economist at Deutsche Bank Securities, said. Nearly one in six American workers has lost a job in recent weeks.

Delays in delivering benefits, though, are as troubling as the sheer magnitude of the figures, he said. Such problems not only create immediate hardships, but also affect the shape of the recovery when the pandemic eases.

Laid-off workers need money quickly so that they can continue to pay rent and credit card bills and buy groceries. If they can’t, Mr. Slok said, the hole that the larger economy has fallen into “gets deeper and deeper, and more difficult to crawl out of.”

Hours after the Labor Department report, the House passed a $484 billion coronavirus relief package to replenish a depleted small-business loan program and fund hospitals and testing. The Senate approved the bill earlier this week.

Even as Congress continues to provide aid, distribution has remained challenging. According to the Labor Department, only 10 states have started making payments under the federal Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program, which extends coverage to freelancers, self-employed workers and part-timers. Most states have not even completed the system needed to start the process.

Ohio, for example, will not start processing claims under the expanded federal eligibility criteria until May 15. Recipients whose state benefits ran out, but who can apply for extended federal benefits, will not begin to have their claims processed until May 1.

Pennsylvania opened its website for residents to file for the federal program a few days ago, but some applicants were mistakenly told that they were ineligible after filling out the forms. The state has given no timetable for when benefits might be paid.

Reports of delays, interruptions and glitches continue to come in from workers who have been unable to get into the system, from others who filed for regular state benefits but have yet to receive them, and from applicants who say they have been unfairly turned down and unable to appeal.

Florida has paid just 17 percent of the claims filed since March 15, according to the state’s Department of Economic Opportunity.

“Speed matters” when it comes to government assistance, said Carl Tannenbaum, chief economist at Northern Trust. Speed can mean the difference between a company’s survival and its failure, or between making a home mortgage payment and facing foreclosure.

There is “a race between policy and a pandemic,” Mr. Tannenbaum said, and in many places, it is clear that the response has been “very uneven.”

Using data reported by the Labor Department for March 14 to April 11, the Economic Policy Institute, a liberal research group, estimated that seven in 10 applicants were receiving benefits. That left seven million other jobless workers who had filed claims but were still waiting for relief.

States manage their own unemployment insurance programs and set the level of benefits and eligibility rules. Now they are responsible for administering federal emergency benefits that provide payments for an additional 13 weeks, cover previously ineligible workers and add $600 to the regular weekly check.

So far, 44 states have begun to send the $600 supplement to jobless workers who qualified under state rules, the Labor Department said. Only two — Kentucky and Minnesota — have extended federal benefits to workers who have used up their state allotment.

With government phones and websites clogged and drop-in centers closed, legal aid lawyers around the country are fielding complaints from people who say they don’t know where else to turn.

“Our office has received thousands of calls,” said John Tirpak, a lawyer with the Unemployment Law Project, a nonprofit group in Washington.

People with disabilities and nonnative English speakers have had particular problems, he said.

Even those able to file initially say they have had trouble getting back into the system as required weekly to recertify their claims.

Colin Harris of Marysville, Wash., got a letter on March 31 from the state’s unemployment insurance office saying he was eligible for benefits after being laid off as a quality inspector at Safran Cabin, an aerospace company. He submitted claims two weeks in a row and heard nothing. When he submitted his next claim, he was told that he had been disqualified. He has tried calling more than 200 times since then, with no luck.

“And that’s still where I am right now,” he said, “unable to talk to somebody to find out what the issue is.” If he had not received a $1,200 stimulus check from the federal government, he said, he would not have been able to make his mortgage payment.

Last week’s tally of new claims was lower than each of the previous three weeks. But millions of additional claims are still expected to stream in from around the country over the next month, while hiring remains piddling.

States are frantically trying to catch up. California, which has processed 2.7 million claims over the last four weeks, opened a second call center on Monday. New York, which has deployed 3,100 people to answer the telephone, said this week that it had reduced the backlog that accumulated by April 8 to 4,305 from 275,000.

Florida had the largest increase in initial claims last week, although the state figures, unlike the national total, are not seasonally adjusted. That increase could be a sign that jobless workers finally got access to the system after delays, but it is impossible to assess how many potential applicants have still failed to get in.

The 10 states that have started making Pandemic Unemployment Assistance payments to workers who would not normally qualify under state guidelines are Alabama, Colorado, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Texas and Utah.

Pain is everywhere, but it is most widespread among the most vulnerable.

In a survey that the Pew Research Center released on Tuesday, 52 percent of low-income households — below $37,500 a year for a family of three — said someone in the household had lost a job because of the coronavirus, compared with 32 percent of upper-income ones (with earnings over $112,600). Forty-two percent of families in the middle have been affected as well.

Those without a college education have taken a disproportionate hit, as have Hispanics and African-Americans, the survey found.

An outsize share of jobless claims have also been filed by women, according to an analysis from the Fuller Project, a nonprofit journalism organization that focuses on women.

Josalyn Taylor, 31, learned that she was out of a job on March 16. “I clocked in at 3 o’clock, and by 3:30 my boss called me and told me we were going to shut down for three weeks,” said Ms. Taylor, an assistant manager at Cicis Pizza in Galveston, Tex. The restaurant has yet to reopen.

Two days later, she applied for unemployment insurance, but she kept receiving a message that a claim was already active for her Social Security number and that she could not file. She has tried to clear up the matter hundreds of times — online, by phone and through the Texas Workforce Commission’s site on Facebook — with no luck.

“I used my stimulus check to pay my light bill, and I’m using that to keep groceries and stuff in the house,” said Ms. Taylor, who is five months pregnant. “But other than that, I don’t have any other income, and I’m almost out of money.”

The first wave of layoffs most heavily whacked the restaurant, travel, personal care, retail and manufacturing industries, but the damage has spread to a much broader range of sectors.

At the online job site Indeed, for example, postings for software development jobs are down nearly 30 percent from last year, while listings for finance and banking openings are down more than 40 percent.

New layoffs are expected to ease over the next couple of months, but the damage to the economy is likely to last much longer. In a matter of weeks, the shutdown has more than erased 10 years of net job gains — more than 19 million jobs.

Health and education are going to revive relatively quickly, said Rick Rieder, chief investment officer for global fixed income at BlackRock, but leisure and hospitality are going to take a lot longer.

“A lot of the people who have been furloughed won’t come back,” he said. “Companies will either close or decide not to take back those workers.”

Over the past decade, the employment landscape has shifted substantially as new types of jobs have appeared and old categories have disappeared. The U.S. economy, Mr. Rieder said, is “going to go through another period of evolution.”