We find the questions, “What makes a great leader?” and “What does great leadership mean in practice?” to be really interesting.

We have seen, for example, the following types of people as leaders: (1) people who appear to have been born to lead and excel as leaders, (2) people anointed as leaders or future leaders who had bold personalities, a certain presence and/or great charisma disappoint completely as leaders, (3) hardworking, organized people without bold personalities who organizations may not have expected to be top leaders grow into their roles and lead organizations to great results.

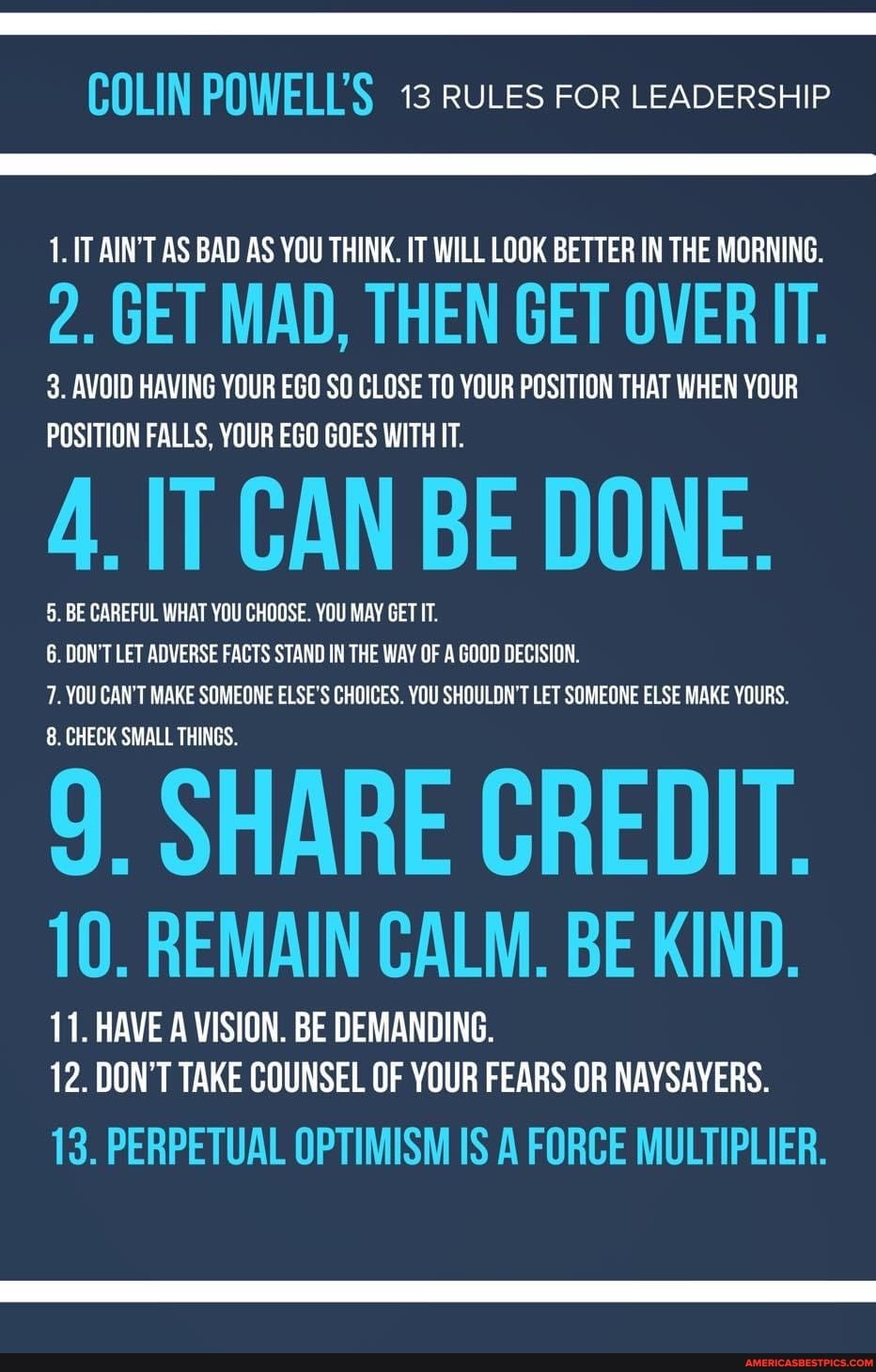

The greatest leaders leave an organization better than they found it. They leave it in a position to thrive long after they are gone. They have the ability to deliver results today while improving and preparing the organization for tomorrow. Great leaders, as stated by some, have a vision and plan, can build great teams, can motivate the team to pursue and achieve the plan, can take in feedback and adjust the plan as needed.

Here are seven thoughts on great leadership.

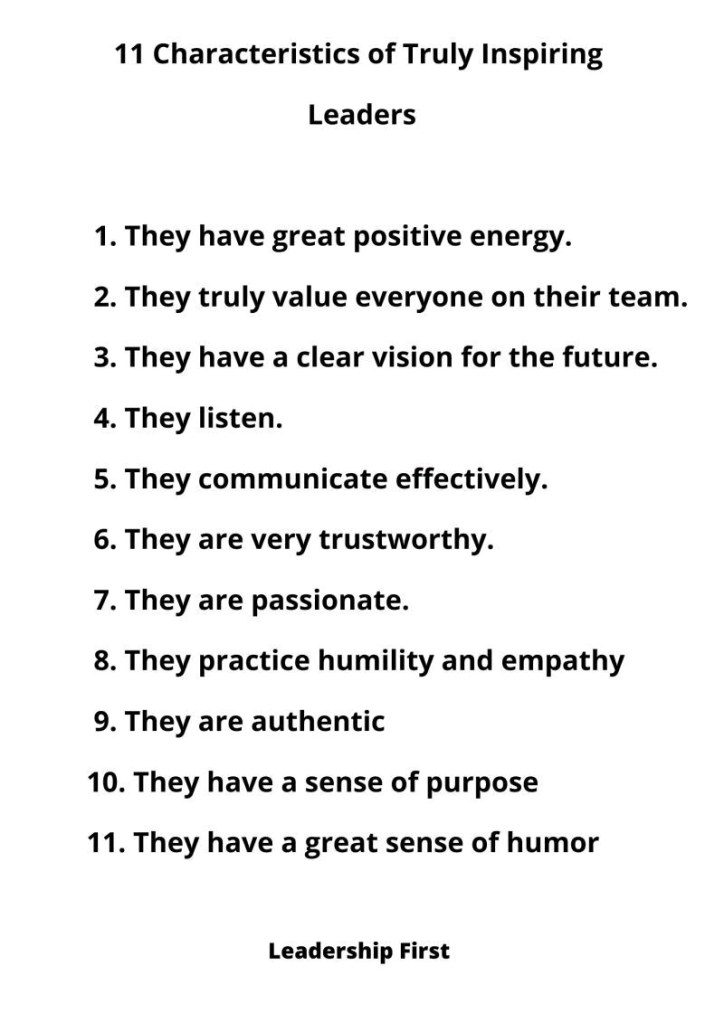

1. Great leaders are engaged, excited and passionate about success. Great leaders remain excited about what they are doing and what their team is trying to accomplish. Teams sense whether a leader is engaged or not. It does not take long to detect. It is the unusual leader who can stay enthusiastic and in top form in a position for more than 10 to 20 years; for many, the attention span is less. The phrase “lame duck leader” often applies to those who are still in office despite losing their spark. When leaders find they are losing excitement or engagement, it is time to step down from leadership or take time to rediscover themselves. An excited and engaged leader is critical to success.

We should not confuse passion and excitement with a huge or “rah-rah” personality. A great leader can have a winning personality, and most have excellent people skills, but those two things are only part of the picture. Great leaders are more than mascots or faces of a company — they are engaged with their teams. They are constantly talking to, communicating with, seeing and visiting their teams. They know what is going on with their teams, they know what is going on with their key customers, and they know what is going on with the business.

2. Great leaders build teams and the next level of leaders. The greatest accomplishment of a leader may be building the next level of leadership in a way where the leader is less needed. This is so important to the organization and requires tremendous energy from current leadership, yet it’s not always a leader’s first and foremost goal.

An elite team can go exponentially further and accomplish a great deal more than an elite leader. Anyone who has built an organization beyond a few people understands the importance of great teams and colleagues. When a high-performing team is built, the leader remains important. However, more and more, you can identify a great leader or manager by how special their team is. When a team is magnificent, it is a lot easier to be a great leader or manager. A core concept in Jim Collins’ Good to Great is to build great teams and then set plans. If one has great people, a company or team can then accomplish all kinds of things.

There is a common misconception that leaders welcome their team’s elite performance because it means the leader can work less. We find this could not be further from the truth. Great leaders know that nobody likes working harder than their boss. This adage holds true whether a leader has been in the field for five years or 50. The scope and role of the leader may change as the team grows more adept, elite and accomplished. Exceptional leaders give others space to lead, opportunities to shine and chances to succeed, but this should not be misinterpreted as leaders stepping away out of ambivalence or putting their feet up.

3. Great leaders have big goals and set clear plans. Great leaders set goals for their teams and organizations that are exciting, interesting and far bigger than themselves. The leader needs a goal that one can point to as, “This is what we are trying to be,” or, “This is what we are trying to accomplish.” There’s nothing worse than leaders who transparently appear to get ahead for themselves or accomplish their own goals versus the organization’s or team’s goals.

The late Apple CEO and co-founder Steve Jobs and former GE CEO Jack Welch are examples of great leaders who set big goals. Mr. Welch had the core goal to be No. 1 or No. 2 in any market — or not be in the market at all. It is also critical that the goal is well communicated to the team and that key decisions are consistent with the goal. No plan or strategy is perfect. However, most organizations and teams do far better with a plan and strategy than without. Often, the plan is imperfect but adjusted over time. Either way, in nearly every situation, an imperfect plan is far superior to no plan.

4. Great leaders generally don’t micromanage. High-caliber leaders develop great leaders and teams and allow their teams to excel, perform and grow. They constantly look at benchmarks, hold people accountable and follow up with them. However, on a day-to-day and moment-to-moment basis, their teams are given lots of latitude and autonomy. This is coupled with follow-up and looking at what is accomplished. Warren Buffett may be the world’s best example of a leader who has great CEOs, holds them accountable and doesn’t micromanage them.

Some of the best leaders we have seen recognize when they have an amazing leader working with them. In those situations, the best of leaders can set their egos aside and largely allow the next in line to take credit and lead.

5. Great leaders praise often and recognize contributions. A great leader understands that part of team-building is constantly looking for what people are doing well and encouraging more of it. Great leaders provide praise, recognize what is done well and motivate more of that to be done. They look for what people do exceptionally well, and they look to promote those doing great things. They are constantly looking for the next opportunity for people.

6. Great leaders are not afraid to make hard personnel decisions. The best leaders understand that not everyone is a fit for every job. They are not willing to tolerate mediocrity or toxicity. This doesn’t mean they have a quick trigger. It does mean that they constantly compare current performance to great performance and try to fit people in spots where their performance can excel. For example, someone who is not great at something might be given another try at a different role where they may shine. One of the best leaders I ever witnessed subscribed to the view that it was very hard to change people. He counseled to be fair and patient, but that it was easier to change the person than change a person. In essence, sometimes it’s easier to replace a person than change how a person behaves.

7. Great leaders are emotionally mature. Great leaders do not fly off the handle or make rash decisions, but they do follow their instincts. A remarkable leader does not react to every issue with a great deal of stress. Rather, he or she can take things in, move forward and keep a team on board. A leader’s ability to manage emotions — both his or her own and those of team members — is critical. While great leaders often act with urgency and intent, they too embrace common sense approaches of “sleep on it” or “no sudden movements” when faced with volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity. They recognize the repercussions of their decisions and movements, and in turn give them the time, thought and reflection they deserve.