I have been both a frontline officer and a staff officer at

a health system. I started a solo practice in 1977 and

cared for my rheumatology, internal medicine and

geriatrics patients in inpatient and outpatient settings.

After 23 years in my solo practice, I served 18 years as

President and CEO of a profitable, CMS 5-star, 715-bed,

two-hospital healthcare system.

From 2015 to 2020, our health system team added

0.6 years of healthy life expectancy for 400,000 folks

across the socioeconomic spectrum. We simultaneously

decreased healthcare costs 54% for 6,000 colleagues and

family members. With our mentoring, four other large,

self-insured organizations enjoyed similar measurable

results. We wanted to put our healthcare system out of

business. Who wants to spend a night in a hospital?

During the frontline part of my career, I had the privilege

of “Being in the Room Where It Happens,” be it the

examination room at the start of a patient encounter, or

at the end of life providing comfort and consoling family.

Subsequently, I sat at the head of the table, responsible for

most of the hospital care in Southwest Florida. [1]

Many folks commenting on healthcare have never touched

a patient nor led a large system. Outside consultants, no

matter how competent, have vicarious experience that

creates a different perspective.

At this point in my career, I have the luxury of promoting

what I believe is in the best interests of patients —

prevention and quality outcomes. Keeping folks healthy and

changing the healthcare industry’s focus from a “repair shop”

mentality to a “prevention program” will save the industry

and country from bankruptcy. Avoiding well-meaning but

inadvertent suboptimal care by restructuring healthcare

delivery avoids misery and saves lives.

RESPONDING TO AN ATTACK

Preemptive reinvention is much wiser than responding to an

attack. Unfortunately, few industries embrace prevention. The

entire healthcare industry, including health systems, physicians,

non-physician caregivers, device manufacturers, pharmaceutical

firms, and medical insurers, is stressed because most are

experiencing serious profit margin squeeze. Simultaneously

the public has ongoing concerns about healthcare costs. While

some medical insurance companies enjoyed lavish profits during

COVID, most of the industry suffered. Examples abound, and

Paul Keckley, considered a dean among long-time observers of

the medical field, recently highlighted some striking year-end

observations for 2022. [2]

Recent Siege Examples

Transparency is generally good but can and has led to tarnishing

the noble profession of caring for others. Namely, once a

sector starts bleeding, others come along, exacerbating the

exsanguination. Current literature is full of unflattering public

articles that seem to self-perpetuate, and I’ve highlighted

standout samples below.

- The Federal Government is the largest spender in the

healthcare industry and therefore the most influential. Not

surprisingly, congressional lobbying was intense during

the last two weeks of 2022 in a partially successful effort

to ameliorate spending cuts for Medicare payments for

physicians and hospitals. Lobbying spend by Big Pharma,

Blue Cross/Blue Shield, American Hospital Association, and

American Medical Association are all in the top ten spenders

again. [3, 4, 5] These organizations aren’t lobbying for

prevention, they’re lobbying to keep the status quo. - Concern about consistent quality should always be top of

mind. “Diagnostic Errors in the Emergency Department: A

Systematic Review,” shared by the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality, compiled 279 studies showing a

nearly 6% error rate for the 130 million people who visit

an ED yearly. Stroke, heart attack, aortic aneurysm, spinal

cord injury, and venous thromboembolism were the most

common harms. The defense of diagnostic errors in emergency

situations is deemed of secondary importance to stabilizing

the patient for subsequent diagnosing. Keeping patients alive

trumps everything. Commonly, patient ED presentations are

not clear-cut with both false positive and negative findings.

Retrospectively, what was obscure can become obvious. [6, 7] - Spending mirrors motivations. The Wall Street Journal article

“Many Hospitals Get Big Drug Discounts. That Doesn’t Mean

Markdowns for Patients” lays out how the savings from a

decades-old federal program that offers big drug discounts

to hospitals generally stay with the hospitals. Hospitals can

chose to sell the prescriptions to patients and their insurers for much more than the discounted price. Originally the legislation was designed for resource-challenged communities, but now some hospitals in these programs are profiting from wealthy folks paying normal prices and the hospitals keeping the difference. [8] - “Hundreds of Hospitals Sue Patients or Threaten Their Credit,

a KHN Investigation Finds. Does Yours?” Medical debt is a

large and growing problem for both patients and providers.

Healthcare systems employ collection agencies that

typically assess and screen a patient’s ability to pay. If the

credit agency determines a patient has resources and has

avoided paying his/her debt, the health system send those

bills to a collection agency. Most often legitimately

impoverished folks are left alone, but about two-thirds

of patients who could pay but lack adequate medical

insurance face lawsuits and other legal actions attempting

to collect payment including garnishing wages or placing

liens on property. [9] - “Hospital Monopolies Are Destroying Health Care Value,”

written by Rep. Victoria Spartz (R-Ind.) in The Hill, includes

a statement attributed to Adam Smith’s The Wealth of

Nations, “that the law which facilitates consolidation ends in

a conspiracy against the public to raise prices.” The country

has seen over 1,500 hospital mergers in the past twenty

years — an example of horizontal consolidation. Hospitals

also consolidate vertically by acquiring physician practices.

As of January 2022, 74 percent of physicians work directly for

hospitals, healthcare systems, other physicians, or corporate

entities, causing not only the loss of independent physicians

but also tighter control of pricing and financial issues. [10]

The healthcare industry is an attractive target to examine.

Everyone has had meaningful healthcare experiences, many have

had expensive and impactful experiences. Although patients do

not typically understand the complexity of providing a diagnosis,

treatment, and prognosis, the care receiver may compare the

experience to less-complex interactions outside healthcare that

are customer centric and more satisfying.

PROFIT-MARGIN SQUEEZE

Both nonprofit and for-profit hospitals must publish financial

statements. Three major bond rating agencies (Fitch Ratings,

Moody’s Investors Service, and S & P Global Ratings) and

other respected observers like KaufmanHall, collate, review,

and analyze this publicly available information and rate health

systems’ financial stability.

One measure of healthcare system’s financial strength is

operating margin, the amount of profit or loss from caring

for patients. In January of 2023 the median, or middle value,

of hospital operating margin index was -1.0%, which is an

improvement from January 2022 but still lags 2021 and 2020.

Erik Swanson, SVP at KaufmanHall, says 2022,

“Is shaping up to be one of the worst financial years on

record for hospitals. Expense pressures — particularly

with the cost of labor — outpaced revenues and drove

poor performance. While emergency department visits

and operating room minutes increased slightly, hospitals

struggled to discharge patients due to internal staffing

shortages and shortages at post-acute facilities,” [11]

Another force exacerbating health system finance is the

competent, if relatively new retailers (CVS, Walmart, Walgreens,

and others) that provide routine outpatient care affordably.

Ninety percent of Americans live within ten miles of a Walmart

and 50% visit weekly. CVS and Walgreens enjoy similar

penetration. Profit-margin squeeze, combined with new

convenient options to obtain routine care locally, will continue

disrupting legacy healthcare systems.

Providers generate profits when patients access care.

Additionally, “easy” profitable outpatient care can and has

switched to telemedicine. Kaiser-Permanente (KP), even before

the pandemic, provided about 50% of the system’s care through

virtual visits. Insurance companies profit when services are

provided efficiently or when members don’t use services.

KP has the enviable position of being both the provider

and payor for their members. The balance between KP’s

insurance company and provider company favors efficient

use of limited resources. Since COVID, 80% of all KP’s visits are

virtual, a fact that decreases overhead, resulting in improved

profit margins. [12]

On the other hand, KP does feel the profit-margin squeeze

because labor costs have risen. To avoid a nurse labor strike,

KP gave 21,000 nurses and nurse practitioners a 22.5% raise over

four years. KP’s most recent quarter reported a net loss of $1.5B,

possibly due to increased overhead. [13]

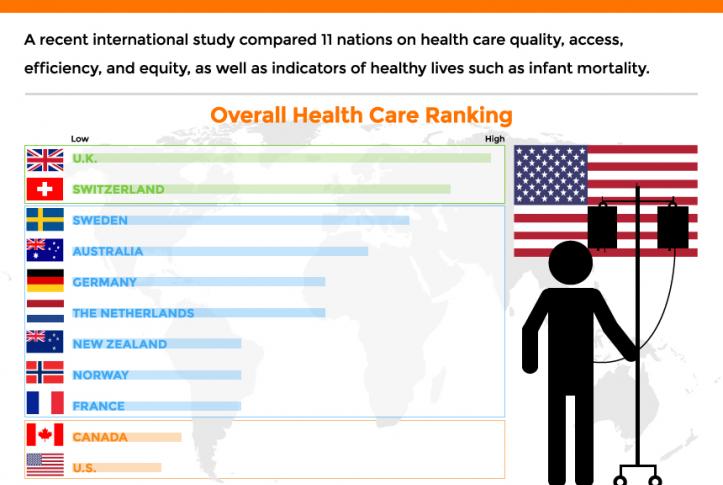

The public, governmental agencies, and some healthcare leaders

are searching for a more efficient system with better outcomes

at a lower cost. Our nation cannot continue to spend the most

money of any developed nation and have the worst outcomes.

In a globally competitive world, limited resources must go to

effective healthcare, balanced with education, infrastructure, the

environment, and other societal needs. A new healthcare model

could satisfy all these desires and needs.

Even iconic giants are starting to feel the pain of recent annual

losses in the billions. Ascension Health, Cleveland Clinic,

Jefferson Health, Massachusetts General Hospital, ProMedica,

Providence, UPMC, and many others have gone from stable

and sustainable to stressed and uncertain. Mayo Clinic had

been a notable exception, but recently even this esteemed

system’s profit dropped by more than 50% in 2022 with higher

wage and supply costs up, according to this Modern Healthcare

summary. [14]

The alarming point is even the big multigenerational health

system leaders who believed they had fortress balance sheets

are struggling. Those systems with decades of financial success

and esteemed reputations are in jeopardy. Changing leadership

doesn’t change the new environment.

Nonprofit healthcare systems’ income typically comes from three

sources — operations, namely caring for patients in ways that are

now evolving as noted above; investments, which are inherently

risky evidence by this past year’s record losses; and philanthropy,

which remains fickle particularly when other investment returns

disappoint potential donors. For-profit healthcare systems don’t

have the luxury of philanthropic support but typically are more

efficient with scale and scope.

The most stable and predictable source of revenue in the

past was from patient care. As the healthcare industry’s cost

to society continues to increase above 20% of the GDP, most

medically self-insured employers and other payors will search for

efficiencies. Like it or not, persistently negative profit margins

will transform healthcare.

Demand for nurses, physicians, and support folks is increasing,

with many shortages looming near term. Labor costs and burnout

have become pressing stresses, but more efficient delivery of

care and better tools can ameliorate the stress somewhat. If

structural process and technology tools can improve productivity

per employee, the long-term supply of clinicians may keep up.

Additionally, a decreased demand for care resulting from an

effective prevention strategy also could help.

Most other successful industries work hard to produce products

or services with fewer people. Remember what the industrial

revolution did for America by increasing the productivity of each

person in the early 1900s. Thereafter, manufacturing needed

fewer employees.

PATIENTS’ NEEDS AND DESIRES

Patients want to live a long, happy and healthy life. The best

way to do this is to avoid illness, which patients can do with

prevention because 80% of disease is self-inflicted. When

prevention fails, or the 20% of unstoppable episodic illness kicks

in, patients should seek the best care.

The choice of the “best care” should not necessarily rest just on

convenience but rather objective outcomes. Closest to home may

be important for take-out food, but not healthcare.

Care typically can be divided into three categories — acute,

urgent, and elective. Common examples of acute care include

childbirth, heart attack, stroke, major trauma, overdoses, ruptured

major blood vessel, and similar immediate, life-threatening

conditions. Urgent intervention examples include an acute

abdomen, gall bladder inflammation, appendicitis, severe

undiagnosed pain and other conditions that typically have

positive outcomes even with a modest delay of a few hours.

Most every other condition can be cared for in an appropriate

timeframe that allows for a car trip of a few hours. These illnesses

can range in severity from benign that typically resolve on their

own to serious, which are life-threatening if left undiagnosed and

untreated. Musculoskeletal aches are benign while cancer is life-threatening if not identified and treated.

Getting the right diagnosis and treatment for both benign and

malignant conditions is crucial but we’re not even near perfect for

either. That’s unsettling.

In a 2017 study,

“Mayo Clinic reports that as many as 88 percent of those

patients [who travel to Mayo] go home [after getting a

second opinion] with a new or refined diagnosis — changing

their care plan and potentially their lives. Conversely, only

12 percent receive confirmation that the original diagnosis

was complete and correct. In 21 percent of the cases, the

diagnosis was completely changed; and 66 percent of

patients received a refined or redefined diagnosis. There

were no significant differences between provider types

[physician and non-physician caregivers].” [15]

The frequency of significant mis- or refined-diagnosis and

treatment should send chills up your spine. With healthcare

we are not talking about trivial concerns like a bad meal at a

restaurant, we are discussing life-threatening risks. Making an

initial, correct first decision has a tremendous influence on

your outcome.

Sleeping in your own bed is nice but secondary to obtaining the

best outcome possible, even if car or plane travel are necessary.

For urgent and elective diagnosis/treatment, travel may be a

good option. Acute illness usually doesn’t permit a few hours of grace, although a surprising number of stroke and heart attack victims delay treatment through denial or overnight timing. But even most of these delayed, recognized illnesses usually survive. And urgent and elective care gives the patient the luxury of some time to get to a location that delivers proven, objective outcomes, not necessarily the one closest to home.

Measuring quality in healthcare has traditionally been difficult for the average patient. Roadside billboards, commercials, displays at major sporting events, fancy logos, name changes and image building campaigns do not relate to quality. Confusingly, some heavily advertised metrics rely on a combination of subjective reputational and lagging objective measures. Most consumers don’t know enough about the sources of information to understand which ratings are meaningful to outcomes.

Arguably, hospital quality star ratings created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are the best information for potential patients to rate hospital mortality, safety, readmission, patient experience, and timely/effective care. These five categories combine 47 of the more than 100 measures CMS publicly reports. [16]

A 2017 JAMA article by lead author Dr. Ashish Jha said:

“Found that a higher CMS star rating was associated with lower patient mortality and readmissions. It is reassuring that patients can use the star ratings in guiding their health care seeking decisions given that hospitals with more stars not only offer a better experience of care, but also have lower mortality and readmissions.”

The study included only Medicare patients who typically are over

65, and the differences were most apparent at the extremes,

nevertheless,

“These findings should be encouraging for policymakers

and consumers; choosing 5-star hospitals does not seem to

lead to worse outcomes and in fact may be driving patients

to better institutions.” [17]

Developing more 5-star hospitals is not only better and safer

for patients but also will save resources by avoiding expensive

complications and suffering.

As a patient, doing your homework before you have an urgent or

elective need can change your outcome for the better. Driving a

couple of hours to a CMS 5-star hospital or flying to a specialty

hospital for an elective procedure could make a difference.

Business case studies have noted that hospitals with a focus on

a specific condition deliver improved outcomes while becoming

more efficient. [18] Similarly, specialty surgical areas within

general hospitals have also been effective in improving quality

while reducing costs. Mayo Clinic demonstrated this with its

cardiac surgery department. [19] A similar example is Shouldice

Hospital near Toronto, a focused factory specializing in hernia

repairs. In the last 75 years, the Shouldice team has completed

four hundred thousand hernia repairs, mostly performed under

local anesthesia with the patient walking to and from the

operating room. [20] [21]

THE BOTTOM LINE

The Mayo Brother’s quote, “The patient’s needs come first,” is

more relevant today than when first articulated over a century

ago. Driving treatment into distinct categories of acute, urgent,

and elective, with subsequent directing care to the appropriate

facilities, improves the entire care process for the patient. The

saved resources can fund prevention and decrease the need for

future care. The healthcare industry’s focus has been on sickness,

not prevention. The virtuous cycle’s flywheel effect of distinct

categories for care and embracing prevention of illness will decrease

misery and lower the percentage of GDP devoted to healthcare.

Editor’s note: This is a multi-part series on reinventing the healthcare

industry. Part 2 addresses physicians, non-physician caregivers, and

communities’ responses to the coming transformation.