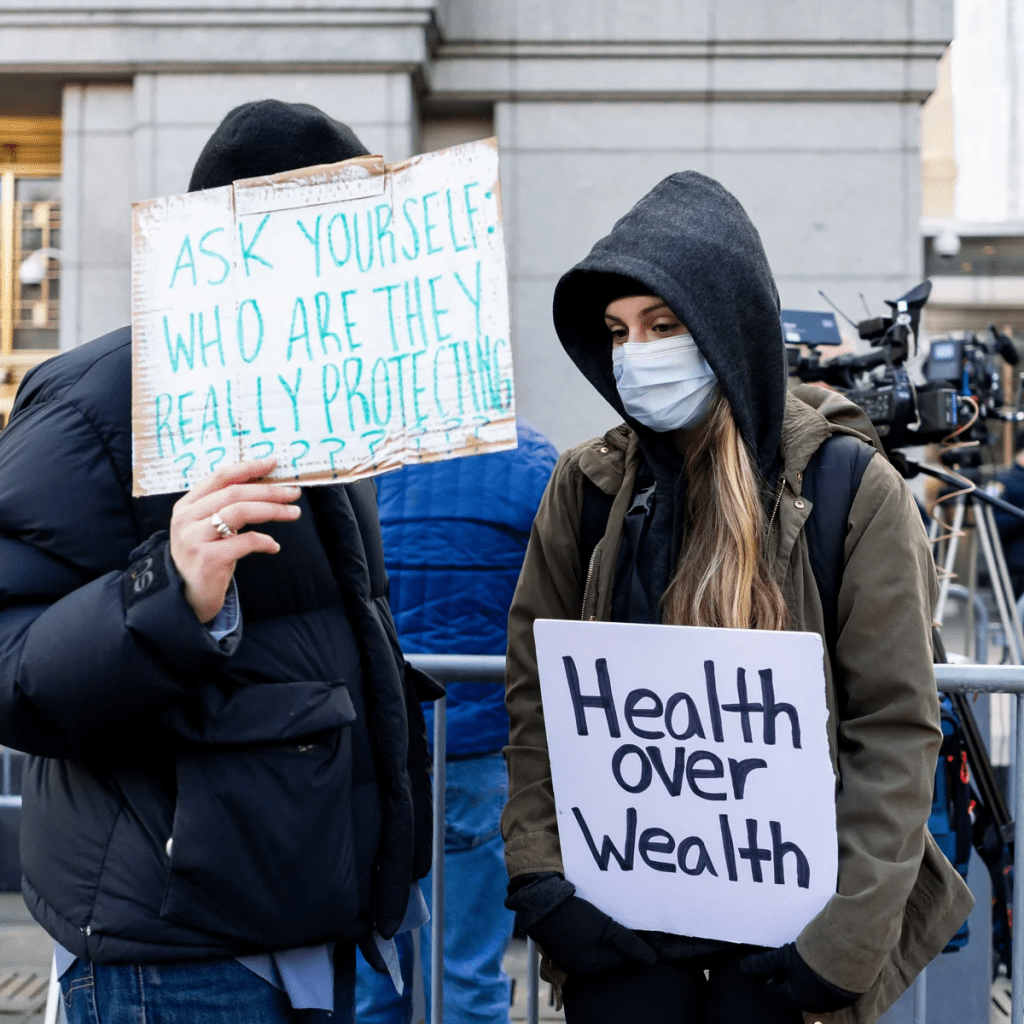

Since the murder of UnitedHealth executive Brian Thompson in New York City December 4, 2024, attention to health insurers has heightened. National media coverage has been brutal. Polls have chronicled the public’s disdain for rising premiums and increased denials. Hospitals and physicians have amped-up campaigns against prior authorization and inadequate reimbursement. For many health insurers, no news is a good news day. Here’s ChatGPT’s reply to how insurers are depicted:

“Media coverage of US health insurers focuses heavily on the challenges consumers face due to high costs, coverage denials, and complicated policies, often portraying insurers as profit-driven entities that hinder care access. Investigations reveal insurers using technology to deny claims and push for denials during prior authorization, while other reports highlight market concentration and the increasing influence of large companies like UnitedHealth Group and Centene. Media also covers the marketing efforts of insurers, particularly for Medicare Advantage plans, and public frustration with the industry. “

In some ways, it’s understandable. Insurance, by definition, is a bet, especially in healthcare. Private policyholders—individuals and employers– bet the premiums they pay pooled with others will cover the cost of a condition or accident that requires medical care. In the 1960’s, federal and state government made the same bet on behalf of seniors (Medicare) and lower-income or disabled kids and adults (Medicaid). But they’re bets.

But the rub is this: what healthcare products and services costs and their prices are hard to predict and closely-guarded secrets in an industry that declares itself the world’s best. Claims data—one source of tracking utilization—is nearly impossible to access even for employers who cover the majority of U.S. population (56%).

Spending for U.S. healthcare is forecast to increase 54% through 2033 from $5.6 trillion to $8.6 trillion— the result of higher costs for prescription drugs and hospital stays, medical inflation, technology, increased utilization (demand) and administrative costs (overhead). Insurers negotiate rates for these, add their margin and pass them thru to their customers—individuals, employers and government agencies. It’s all done behind the scenes.

The public’s working knowledge of how the health system operates, how it performs and what key players in the ecosystem do is negligible. For most, personal experience with the system is their context. We understand our personal healthiness if so inclined or fortunate to have a continuous primary care relationship. We understand our medications if they solve a problem or don’t. We understand our hospitals if we or a family member use them or occasionally visit, and we understand our insurance when we enroll choosing from affordable options that include the doctors and hospitals we like and when we’re denied services or billed for what insurance doesn’t cover.

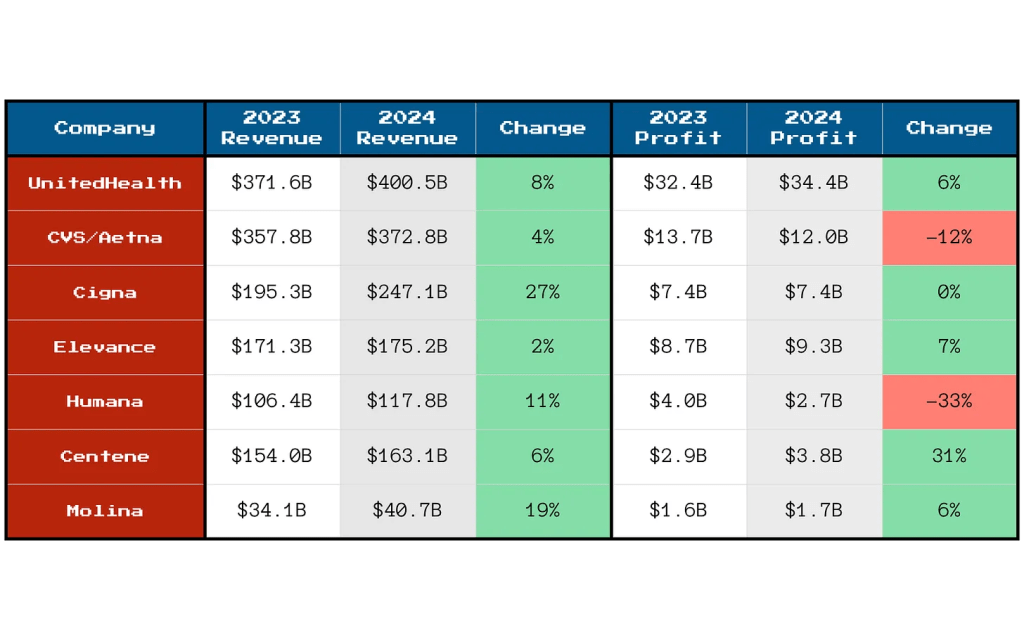

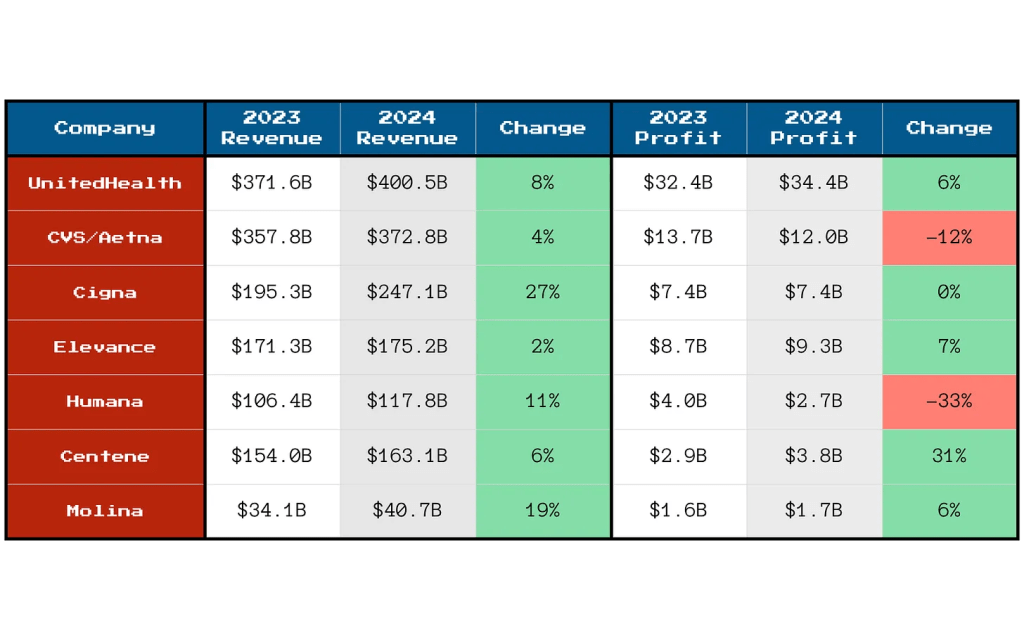

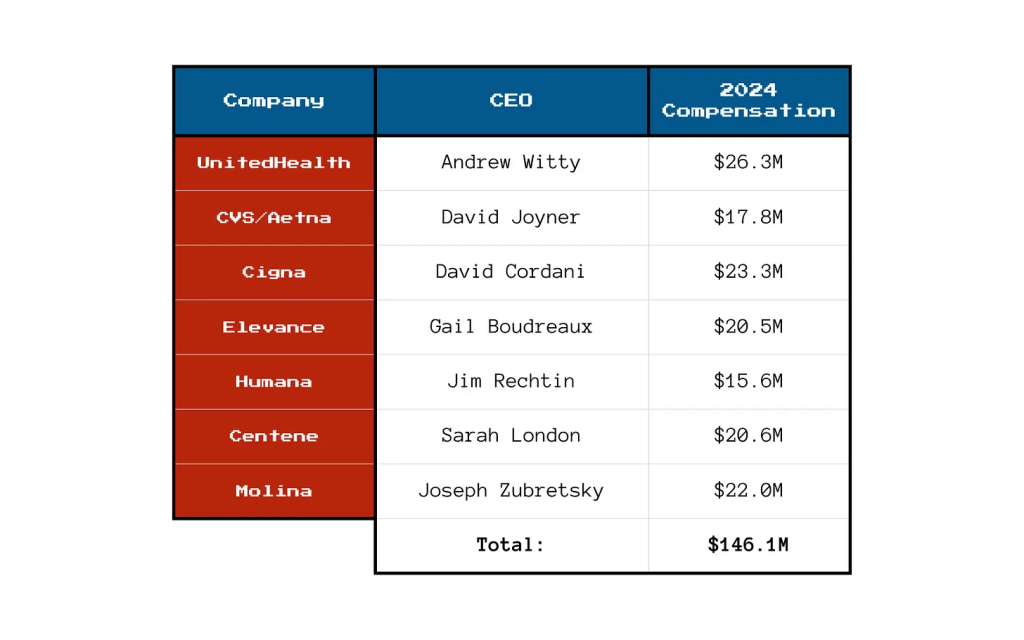

Today, corporate names like UnitedHealth Group, Humana, Cigna, Elevance, CVS Aetna and Centene are the health insurance industry’s big brands, corralling more than 60% of the industry’s private and government enrollment with the rest divided among 1,149 smaller players. Today, the public’s perception of health insurers is negative: most consider insurance a necessary evil with data showing it’s no guarantee against financial ruin. Today, it’s an expensive employee benefit for employers who are looking for alternative options for workforce stability. And only 56% of enrollees trust their health insurer to do what’s best for them.

Ours is a flawed system that’s not sustainable: insurers are part of that problem. It’s premised on dependence: patients depend on providers to define their diagnosis and deliver the treatments/therapeutics and enrollees depend on insurers to handle the logistics of how much they get paid and when. At the point of service, patients pay co-pays and after the fact, get an “explanation of benefits” along with additional out of pocket obligations. Hospitals and physicians fight insurers about what’s reasonable and customary compensation, and patients unable to out-of-pocket obligations are handed off to “revenue cycle specialists” for collection. Wow. Great system! Mark it up, pass it thru and let the chips fall where they may—all under the presumed oversight of state insurance commissioners who are tasked to protect the public’s interests.

Do insurers deserve the animosity they’re facing from employers, hospitals, physicians and their enrollees? Yes, but certainly some more than others. Facts are facts:

- Since 2020, health insurance premium costs have increased 2-4 times faster than household necessities and wages for the average household. Affordability is an issue.

- Denials have increased.

- Enrollee trust and satisfaction with insurers has plummeted.

- And industry profits since 2023 have taken a hit due to post-pandemic pent-up demand, pricey drugs including in-demand GLP-1’s for obesity and increased negotiation leverage by consolidated health systems.

Most Americans think not having health insurance is a bigger risk than going without. But most also think healthcare is fundamental right and the government should guarantee access through universal coverage.

Having private insurance is not the issue: having insurance that ensures access to doctors and hospitals when needed reliably and affordably is their unmet need.

In the weeks ahead, employers will update their employee health benefits options for next year while facing 9-15% higher costs for their coverage. States will decide how they’ll implement work requirements in their Medicaid programs and assess the extent of lost coverage for millions. Insurers who sponsor market place plans suspended by the Big Beautiful Bill will raise their individual premiums hikes 20-70% for the 16 million who are losing their subsidies.

Medicare Advantage (Medicare Part C) insurers will skinny-down the supplements in their offerings and raise premiums alongside Part D increases, And, every insurer will inventory markets served and product portfolio profitability to determine investment opportunities or exit strategies. That’s the calculus every insurer applies every year, adjusting as conditions dictate.

Most private insurers pay little attention to the 8% of Americans who have no coverage; those inclined tend to be smaller community-based plans often associated with hospitals or provider organizations.

Most are concerned about continuity of care for their enrollees: they know 12% had a lapse in their coverage last year, 23% are under-insured and 43% missed a scheduled appointment or treatment due to out-of-pocket costs involved.

And all are concerned about the long-term financial viability of the entire health insurance sector: margins have plummeted since 2020 from 3.1% to 0.8%%, medical loss ratio’s have increased from 98.2% in 2023 to 100.1% last year, premiums increase grew 5.9% while hospital and medical expenses grew $8.9% and so on. The bigger players have residual capital to diversify and grow; others don’t.

Criticism of the health insurance industry is justified for the most part but the rest of the story is key. The U.S. system is broken and everyone knows it. But health insurers are not alone in bearing responsibility for its failure though their role is significant.

The urgent need is for a roadmap to a system of health where the healthiness and well-being of the entire population is true north to its ambition. It’s a system that’s comprehensive, connected, cost-effective and affordable. Protecting turf between sectors, blame and shame rhetoric and perpetuation of public ignorance are non-starters.

PS: Two important events last week weigh heavily on U.S. healthcare’s future:

In Verona, WI, the Epic User Group Meeting showcased the company’s plans for AI featuring 3 new generative AI tools — Emmie for patients, Art for clinicians and Penny for revenue cycle management. Per KLAS, the private company grew its market share to 42% of acute care hospitals and 55% of acute care beds at the end of 2024.

In Jackson Hole, WY, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s annual economic symposium where Fed Chair Jay Powell signaled a likely interest rate cut in its September 16-17 meeting and changes to how the central bank will assess employment status going forward.

Healthcare is labor intense, capital intense and 26% of federal spending in the FY 2026 proposed budget. The Fed through its monetary policies has the power and obligation to foster economic stability. Epic is one of a handful of companies that has the potential to transform the U.S. health system. Transformation of the health system is essential to its sustainability and necessary to the U.S. economic stability since healthcare is 18% of the country’s GDP and its biggest private employer.