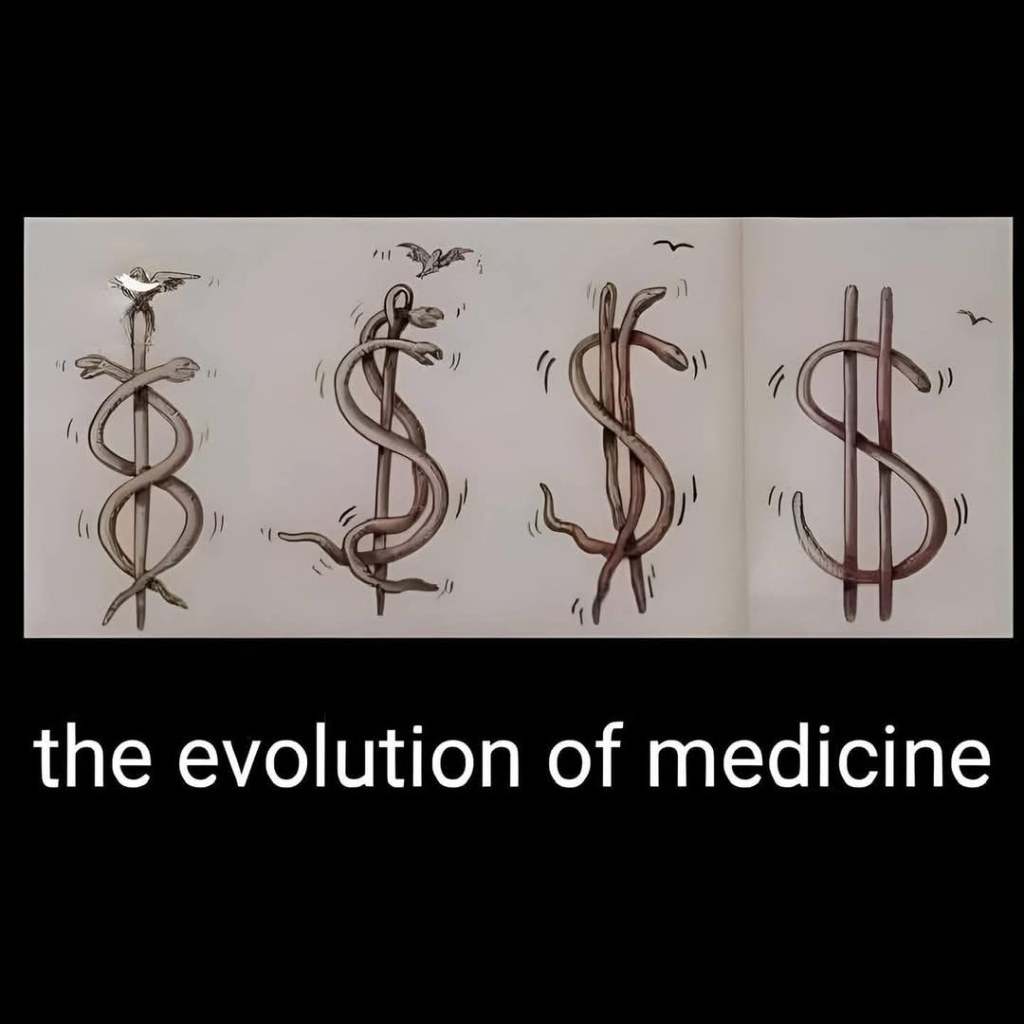

The Fundamental Problem at the Heart of American Health Insurance

Administrative waste, denials, and deadly incentives — the U.S. model shows what happens when profit rules.

The United States is the only country where a health insurance executive has been gunned down in the street. But that’s not the only thing that’s unique about American health insurance.

Almost all of our peer countries – advanced, free-market democracies — have health insurance companies. In some cases (Germany, Switzerland, Japan), private health insurance is the chief way to pay for medical care. In others (such as Great Britain), private insurance works as a supplement to government-run health care systems. But there’s a fundamental difference between health insurance elsewhere and the U.S. system.

In all the other advanced democracies, basic health insurance is not for profit; the insurers are essentially charities. They exist not to pay large sums to executives and investors, but rather to keep the population healthy by assuring that everyone can get medical care when it’s needed.

America’s health insurance giants are profit-making businesses. Indeed, in the insurers’ quarterly earnings reports to investors, the standard industry term for any sums spent paying people’s medical bills is “medical loss.” They view paying your doctor bill as a loss that subtracts from the dividends they owe their stockholders.

When I studied health care systems around the world, I asked economists and doctors and health ministers why they want health insurance to be a nonprofit endeavor. Everyone gave essentially the same answer:

There’s a fundamental contradiction between insuring a nation’s health and making a profit on health insurance.

Health insurance exists to help people get the preventive care and treatment they need by paying their medical bills. But the way to make a profit on health insurance is to avoid paying medical bills. Accordingly, the U.S. insurance giants have devised ingenious methods for evading payment — schemes like high deductibles, narrow networks of approved doctors, limited lists of permitted drugs, and pre-authorization requirements, so that the insurance adjuster, not your doctor, determines what treatment you get.

Other countries don’t allow those gimmicks. In America, the patient pays twice — first the insurance premium, and then the bill that the insurer declines to pay. That’s why Americans hate health insurance companies — as reflected in the tasteless barrage of angry social media commentary aimed at the victim, not the perpetrator, of the sidewalk shooting in 2024 of UnitedHealthcare’s CEO Brian Thompson in New York City.

Another unique aspect of U.S.-style health insurance is the huge amount of money our big insurers waste on administrative costs. Any insurance plan has administrative expenses; you’ve got to collect the premiums, review the patients’ claims, and get the payments out to doctors and hospitals.

In other countries, the administrative costs are limited to about 5% of premium income; that is, insurers use 95% of all the money they take in to pay medical bills. But the U.S. insurance giants routinely report administrative costs in the range of 15% to 20%.

When the first drafts of the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) were floated on Capitol Hill in 2009, the statutory language called for limiting insurers’ admin costs to 12% of premium income. Then the insurance lobby went to work. The final text of that law allows them to spend up to 20% of their income on salaries, marketing, dividends, and other stuff that doesn’t pay anybody’s hospital bill.

There is one American insurance system, however, that is as thrifty as foreign health insurance plans. Medicare, the federal government’s insurance program for seniors and the disabled, reports administrative costs in the range of 3% — about one-fifth as much as the big private insurers fritter away. And Medicare’s administrators — federal bureaucrats — are paid less than a tenth as much as the executives running the far less efficient private insurance firms.

Americans generally believe that the profit-driven private sector is more efficient and innovative than government. In many cases, that’s true. I wouldn’t want some government agency designing my cell phone or my hiking boots.

But when it comes to health insurance, all the evidence shows that nonprofit and government-run plans provide better coverage at lower cost than the private plans from America’s health insurance giants.

If we were to make basic health insurance a nonprofit endeavor, as it is everywhere else, or put everybody on a public plan like Medicare, the U.S. would save billions and improve our access to life-saving care. Then Americans might stop celebrating on social media when an insurance executive is killed.

Poll results: AGI and the future of medicine

Artificial general intelligence (AGI) refers to AI systems that can match or exceed human cognitive abilities across a wide range of tasks, including complex medical decision-making.

With tech leaders predicting AGI-level capabilities within just a few years, clinicians and patients alike may soon face a historic inflection point: How should these tools be used in healthcare, and what benefits or risks might they bring? Last month’s survey asked your thoughts on these pressing questions. Here are the results:

My thoughts:

I continue to be impressed by the expertise of readers. Your views on artificial general intelligence (AGI) closely align with those of leading technology experts. A clear majority believes that AGI will reach clinical parity within five years. A sizable minority expect it will take longer, and only a small number doubt it will ever happen.

Your answers also highlight where GenAI could have the greatest impact. Most respondents pointed to diagnosis (helping clinicians solve complex or uncertain medical problems) as the No. 1 opportunity. But many also recognized the potential to empower patients: from improving chronic disease management to personalizing care. And unlike the electronic health record, which adds to clinicians’ workloads (and contributes to burnout), GenAI is widely seen by readers as a tool that could relieve some of that burden.

Ultimately, the biggest concern may lie not with the technology, itself, but in who controls it. Like many of you, I worry that if clinicians don’t lead the way, private equity and for-profit companies will. And if they do, they will put revenue above the interests of patients and providers.

Thanks to those who voted. To participate in future surveys, and for access to timely news and opinion on American healthcare, sign up for my free (and ad-free) newsletter Monthly Musings on American Healthcare.

* * *

Dr. Robert Pearl is the former CEO of The Permanente Medical Group, the nation’s largest physician group. He’s a Forbes contributor, bestselling author, Stanford University professor, and host of two healthcare podcasts. Check out Pearl’s newest book, ChatGPT, MD: How AI-Empowered Patients & Doctors Can Take Back Control of American Medicine with all profits going to Doctors Without Borders.

GOP faces ‘big, beautiful’ blowback risk on ObamaCare subsidy cuts

Medicaid cuts have received the lion’s share of attention from critics of Republicans’ sweeping tax cuts legislation, but the GOP’s decision not to extend enhanced ObamaCare subsidies could have a much more immediate impact ahead of next year’s midterms.

Extra subsidies put in place during the coronavirus pandemic are set to expire at the end of the year, and there are few signs Republicans are interested in tackling the issue at all.

To date, only Sens. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) and Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) have spoken publicly about wanting to extend them.

The absence of an extension in the “big, beautiful bill” was especially notable given the sweeping changes the legislation makes to the health care system, and it gives Democrats an easy message: If Republicans in Congress let the subsidies expire at the end of the year, premiums will spike, and millions of people across the country could lose health insurance.

In a statement released last month as the House was debating its version of the bill, House and Senate Democratic health leaders pointed out what they said was GOP hypocrisy.

“Their bill extends hundreds of tax policies that expire at the end of the year. The omission of this policy will cause millions of Americans to lose their health insurance and will raise premiums on 24 million Americans,” wrote Senate Finance Committee ranking member Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), House Ways and Means Committee ranking member Richard Neal (D-Mass.) and House Energy and Commerce Committee ranking member Frank Pallone (D-N.J.).

“The Republican failure to stop this premium spike is a policy choice, and it needs to be recognized as such.”

More than 24 million Americans are enrolled in the insurance marketplace this year, and about 90 percent — more than 22 million people — are receiving enhanced subsidies.

“All of those folks will experience quite large out-of-pocket premium increases,” said Ellen Montz, who helped run the federal ObamaCare exchanges under the Biden administration and is now a managing director with Manatt Health.

“When premiums become less affordable, you have this kind of self-fulfilling prophecy where the youngest and the healthiest people drop out of the marketplace, and then premiums become even less affordable in the next year,” Montz said.

The subsidies have been an extremely important driver of ObamaCare enrollment. Experts say if they were to expire, those gains would be erased.

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), 4.2 million people are projected to lose insurance by 2034 if the subsidies aren’t renewed.

Combined with changes to Medicaid in the new tax cut law, at least 17 million Americans could be uninsured in the next decade.

The enhanced subsidies increase financial help to make health insurance plans more affordable. Eligible applicants can use the credit to lower insurance premium costs upfront or claim the tax break when filing their return.

Premiums are expected to increase by more than 75 percent on average, with people in some states seeing their payments more than double, according to health research group KFF.

Devon Trolley, executive director of Pennie, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) exchange in Pennsylvania, said she expects at least a 30 percent drop in enrollment if the subsidies expire.

The state starts ramping up its open enrollment infrastructure in mid-August, she said, so time is running short for Congress to act.

“The only vehicle left for funding the tax credits, if they were to extend them, would be the government funding bill with a deadline of September 30, which we really see as the last possible chance for Congress to do anything,” Trolley said.

Trolley said three-quarters of enrollees in the state’s exchange have never purchased coverage without the enhanced tax credits in place.

“They don’t know sort of a prior life of when the coverage was 82 percent more expensive. And we are very concerned this is going to come as a huge sticker shock to people, and that is going to significantly erode enrollment,” Trolley said.

The enhanced subsidies were first put into effect during the height of the coronavirus pandemic as part of former President Biden’s 2021 economic recovery law and then extended as part of the Inflation Reduction Act.

The CBO said permanently extending the subsidies would cost $358 billion over the next 10 years.

Republicans have balked at the cost. They argue the credits hide the true cost of the health law and subsidize Americans who don’t need the help. They also argue the subsidies have been a driver of fraudulent enrollment by unscrupulous brokers seeking high commissions.

Sen. Bill Cassidy (R-La.), chair of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, last year said Congress should reject extending the subsidies.

The Republican Study Committee’s 2025 fiscal budget said the subsidies “only perpetuate a never-ending cycle of rising premiums and federal bailouts — with taxpayers forced to foot the bill.”

But since 2020, enrollment in the Affordable Care Act marketplace has grown faster in the states won by President Trump in 2024, primarily rural Southern red states that haven’t expanded Medicaid. Explaining to millions of Americans why their health insurance premiums are suddenly too expensive for them to afford could be politically unpopular for Republicans.

According to a recent KFF survey, 45 percent of Americans who buy their own health insurance through the ACA exchanges identify as Republican or lean Republican. Three in 10 said they identify as “Make America Great Again” supporters.

“So much of that growth has just been a handful of Southern red states … Texas, Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas,” said Cynthia Cox, vice president at KFF and director of the firm’s ACA program. “That’s where I think we’re going to see a lot more people being uninsured.”

The Great Flattening

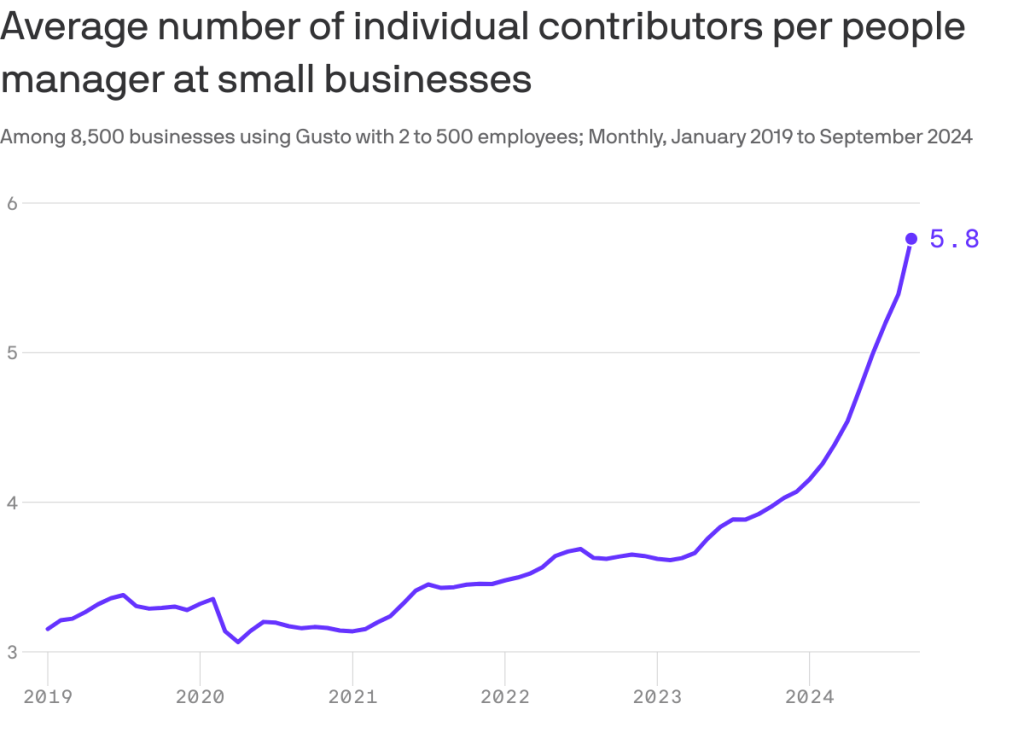

This chart may explain why your boss is taking longer to get back to you lately: They’ve got more underlings to watch over, Axios’ Emily Peck writes from a new analysis.

- Why it matters: Middle managers — i.e., bosses who have bosses — were already quietly going extinct, and now AI may be hastening the process.

By the numbers:

People managers now oversee about twice as many workers as just five years ago.

- There are now nearly six individual contributors per manager at the 8,500 small businesses analyzed in a report by Gusto, which handles payroll for small and medium-sized employers.

- That’s up from a little over three in 2019.

🎨 The big picture:

Big Tech has been shedding middle managers for the past few years, a process that’s been dubbed the Great Flattening.

- Reducing management layers is one of Microsoft’s stated goals in laying off thousands of workers this year as it ramps up its AI strategy.

- Amazon CEO Andy Jassy last year announced an effort to reduce managers (memo).

Cartoon – Importance of Project Leadership

Cartoon – Thought Leadership

Cartoon – Great Leaders are not Born

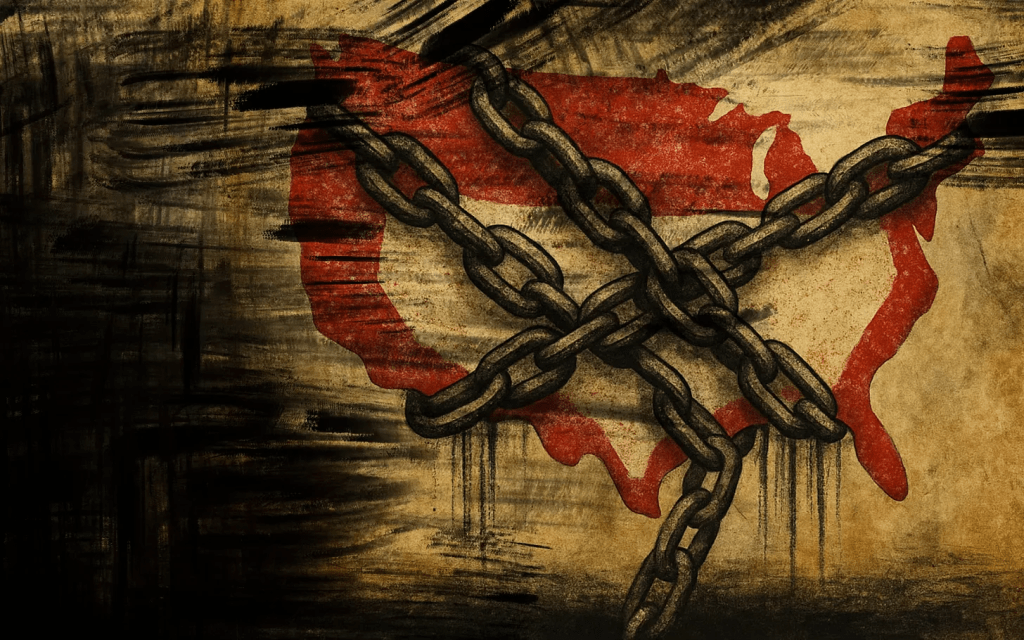

The Perfect Storm has Hit U.S. Healthcare

The perfect storm has hit U.S. healthcare:

- The “Big Beautiful Budget Bill” appears headed for passage with cuts to Medicaid and potentially Medicare likely elements.

- The economy is slowing, with a mild recession a possibility as consumer confidence drops, the housing market slows and uncertainty about tariffs mounts.

- And partisan brinksmanship in state and federal politics has made political hostages of public and rural health safety net programs as demand increases for their services.

Last Wednesday, amidst mounting anxiety about the aftermath of U.S. bunker-bombing in Iran and escalating conflicts in Gaza and Ukraine, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released its report on healthcare spending in 2024 and forecast for 2025-2033:

“National health expenditures are projected to have grown 8.2% in 2024 and to increase 7.1% in 2025, reflecting continued strong growth in the use of health care services and goods.

During the period 2026–27, health spending growth is expected to average 5.6%, partly because of a decrease in the share of the population with health insurance (related to the expiration of temporarily enhanced Marketplace premium tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022) and partly because of an anticipated slowdown in utilization growth from recent highs. Each year for the full 2024–33 projection period, national health care expenditure growth (averaging 5.8%) is expected to outpace that for the gross domestic product (GDP; averaging 4.3%) and to result in a health share of GDP that reaches 20.3% by 2033 (up from 17.6% in 2023) …

Although the projections presented here reflect current law, future legislative and regulatory health policy changes could have a significant impact on the projections of health insurance coverage, health spending trends, and related cost-sharing requirements, and they thus could ultimately affect the health share of GDP by 2033.”

As has been the case for 20 years, spending for healthcare grew faster than the overall economy in 2024. And it is forecast to continue through 2033:

| 2024Baseline | 2033Forecast | % Nominal Chg.2024-2033 | |

| National Health Spending | $5,263B | $8,585B | +63.1% |

| US Population | 337,2M | 354.8M | +5.2% |

| Per capita personal health spending | $13,227 | $20,559 | +55.7% |

| Per capita disposable personal income | $21,626 | $31,486 | +45.6% |

| NHE as % of US GDP | 18.0% | 20.3% | +12.8% |

In its defense, industry insiders call attention to the uniqueness of the business of healthcare:

- ‘Healthcare is a fundamental need: the health system serves everyone.’

- ‘Our aging population, chronic disease prevalence and socioeconomic disparities are drive increased demand for the system’s products and services.’

- ‘The public expects cutting edge technologies, modern facilities, effective medications and the best caregivers and they’re expensive.’

- ‘Burdensome regulatory compliance costs contribute to unnecessary spending and costs.’

And they’re right.

Critics argue the U.S. health system is the world’s most expensive but its results (outcomes) don’t justify its costs. They acknowledge the complexity of the industry but believe “waste, fraud and abuse” are pervasive flaws routinely ignored. And they remind lawmakers that the health economy is profitable to most of its corporate players (investor-owned and not-for-profits) and its executive handsomely compensated.

Healthcare has been hit by a perfect storm at a time when a majority of the public associates it more with corporatization and consolidation than caring. This coalition includes Gen Z adults who can’t afford housing, small employers who’ve cut employee coverage due to costs and large, self-insured employers who trying to navigate around the 10-20% employee health cost increase this year, state and local governments grappling with health costs for their public programs and many more. They’re tired of excuses and think the health system takes advantage of them.

As a percentage of the nation’s GDP and household discretionary spending, healthcare will continue to be disproportionately higher and increasingly concerning. Spending will grow faster than other industries until lawmakers impose price controls and other mechanisms like at least 8 states have begun already.

Most insiders are taking cover and waiting ‘til the storm passes. Some are content to cry foul and blame others. Others will emerge with new vision and purpose centered on reality.

Storm damage is rarely predictable but always consequential. It cannot be ignored. The Perfect has Hit U.S. healthcare. Its impact is not yet known but is certain to be a game changer.

The Fox Guards the Hen House – Translating AHIP’s Commitments to Streamlining Prior Authorization

“We urge the Administration to consider the timing of these policies in the context of the broader scope of requirements and challenges facing the industry that require significant system changes.”

- AHIP, March 13, 2023 (in a letter to CMS Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure responding to CMS’s proposed rule on Advancing Interoperability and Improving Prior Authorization Processes, proposed Final Rule, CMS-0057-P)

“Health insurance plans today announced a series of commitments to streamline, simplify and reduce prior authorization – a critical safeguard to ensure their members’ care is safe, effective, evidence-based and affordable.”

- AHIP, June 23, 2025 (press release announcing voluntary prior authorization reforms)

What a difference two years make.

After lobbying aggressively to delay implementation of the PA reforms proposed by the previous administration (successfully delayed one year and counting), AHIP, the big PR and lobbying group for health insurers, now claims the mantle of reformer, announcing a set of voluntary commitments to streamline prior authorization.

So naturally, the industry’s “commitments” deserve closer scrutiny. Let’s unpack them. As a former health insurance industry executive, I speak their language, so allow me to translate. AHIP, which has no enforcement power, by the way, claims that 48 large insurers will:

- Develop and implement standards for electronic prior authorization using Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources Application Programming Interfaces (FHIR APIs).Translation: CMS is already requiring all insurers to do this by 2027. We might as well take credit preemptively.

- Reduce the volume of in-network medical authorizations. Translation: We already demand hundreds of millions of unnecessary prior authorizations for thousands of procedures and services, so cutting a few (who knows how many?) should be a layup and won’t cut into profits.

- Enhance continuity of care when patients change health plans by honoring a PA decision for a 90-day transition period starting in 2026.Translation: We’re already required to do this in Medicare Advantage. And since we delayed implementation of e-authorization until 2027, we’re in the clear until then anyway.

- Improve communications by providing members with clear explanations for authorization determinations and support for appeals. Translation: We’re already required by state and federal law to do this. We’ll double-check our materials.

- Ensure 80% of prior authorizations are processed in real time and expand new API standards to all lines of business. Translation: We had to promise to hold ourselves accountable to at least one measurable goal. We will set the denominator – we’ll decide which procedures and medications require PA – so we’ll hit this goal, no problem, and we might even use more non-human AI algorithms to do it.

- 6. Ensuring medical review of non-approved requests. Translation: People will be relieved we’re not using robots. And we’ll avoid having Congress insist that reviews must be done by a same-specialty physician, as proposed in the Reducing Medically Unnecessary Delays in Care Act of 2025 (H.R. 2433).

Of course, I wasn’t in the room when AHIP drafted these commitments, so take my translations with a grain of salt. But let’s be honest: These promises are thin on specifics, short on accountability, and devoid of measurable impact.

They also follow a familiar script, blaming physicians for cost escalation by “deviating from evidence-based care” and the “latest research”, while positioning PA as a necessary safeguard to protect patients from “unsafe or inappropriate care.” And largely ignoring how PA routinely delays necessary treatment and harms patients.

It’s also rich coming from an industry still reliant on something called the X12 transaction standard – technology that is now over 40 years old – to process prior authorization requests, while simultaneously pointing the finger at providers for outdated technology and being slow to adopt modern systems. Many insurers did not start accepting electronic submissions of prior authorization until roughly 2019, nearly 20 years after clinicians started using online portals such as MyChart in their regular practice. The claim that providers are the ones behind on technology is another ploy by insurers to dodge scrutiny for their schemes.

We shouldn’t settle for incremental fixes when the system itself is the problem. Nor should we allow the industry that created this problem – and perpetuates it in its own self-interest – to dictate the pace or terms of reforming it.

As we argued in our recent piece, Congress should act to significantly curtail the use of prior authorization, limiting it to a narrow, evidence-based set of high-risk use cases. Insurers should also be required to rapidly adopt smarter, lower-friction cost-control methods, like gold-carding trusted clinicians (if it can be implemented with integrity and fairness), without compromising patient access or clinical autonomy.

Letting the fox design the hen house’s security perimeter won’t protect the hens. It’s time for Congress to build a better fence.