The Four Questions Healthcare Boards must Answer

In 63 days, Americans will know the composition of the 119th Congress and the new occupants of the White House and 11 Governor’s mansions. We’ll learn results of referenda in 10 states about abortion rights (AZ, CO, FL, MD, MO, MT, NE, NV, NY, SD) and see how insurance coverage for infertility (IVF therapy) fares as Californians vote on SB 729. But what we will not learn is the future of the U.S. health system at a critical time of uncertainty.

In 6 years, every baby boomer will be 65 years of age or older. In the next 20 years, the senior population will be 22% of the population–up from 18% today. That’s over 83 million who’ll hit the health system vis a vis Medicare while it is still digesting the tsunami of obesity, a scarcity of workers and unprecedented discontent:

- The majority of voters is dissatisfied with the status quo. 69% think the system is fundamentally flawed and in need of major change vs. 7% who think otherwise. 60% believe it puts its profits above patient care vs. 13% who disagree.

- Employers are fed up: Facing projected cost increases of 9% for employee coverage in 2025, they now reject industry claims of austerity when earnings reports and executive compensation indicate otherwise. They’re poised to push back harder than ever.

- Congress is increasingly antagonistic: A bipartisan coalition in Congress is pushing populist reforms unwelcome by many industry insiders i.e. price transparency for hospitals, price controls for prescription drugs, limits on private equity ownership, constraint on hospital, insurer and physician consolidation, restrictions on tax exemptions of NFP hospitals, site neutral payment policies and many more.

Fanning these flames, media characterizations of targeted healthcare companies as price gouging villains led by highly-paid CEOs is mounting: last week, it was Acadia Health’s turn courtesy of the New York Times’ investigators.

Navigating uncertainty is tough for industries like healthcare where demand s growing, technologies are disrupting how and where services are provided and by whom, and pricing and affordability are hot button issues. And it’s too big to hide: at $5.049 trillion, it represents 17.6% of the U.S. GDP today increasing to 19.7% by 2032. Growing concern about national debt puts healthcare in the crosshairs of policymaker attention:

Per the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget: “In the latest Congressional Budget Office (CBO) baseline, nominal spending is projected to grow from $6.8 trillion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 to $10.3 trillion in 2034. About 87% of this increase is due to three parts of the federal budget: Social Security, federal health care programs, and interest payments on the debt.”

In response, Boards in many healthcare organizations are hearing about the imperative for “transformational change” to embrace artificial intelligence, whole person health, digitization and more. They’re also learning about ways to cut their operating costs and squeeze out operating margins. Bold, long-term strategy is talked about, but most default to less risky, short-term strategies compatible with current operating plans and their leaders’ compensation packages. Thus, “transformational change” takes a back seat to survival or pragmatism for most.

For Boards of U.S. healthcare organizations, the imperative for transformational change is urgent: the future of the U.S. system is not a repeat of its past. But most Boards fail to analyze the future and construct future-state scenarios systematically. Lessons from other industries are instructive.

- Transformational change in mission critical industries occurs over a span of 20-25 years. It starts with discontent with the status quo, then technologies and data that affirm plausible alternatives and private capital that fund scalable alternatives. It’s not overnight.

- Transformational change is not paralyzed by regulatory hurdles. Transformers seek forgiveness, not permission while working to change the regulatory landscape. Advocacy is a critical function in transformer organizations.

- Transformation is welcomed by consumers. Recognition of improved value by end-users—individual consumers—is what institutionalizes transformational success. Transformed industries define success in terms of the specific, transparent and understandable results of their work.

Per McKinsey, only one in 8 organizations is successful in fully implementing transformational change completely but the reward is significant: transformers outperform their competition three-to-one on measures of growth and effectiveness.

I am heading to Colorado Springs this weekend for the Governance Institute. There, I will offer Board leaders four basic questions.

- Is the future of the U.S. health system a repeat of the past or something else?

- How will its structure, roles and responsibilities change?

- How will affordability, quality, innovation and value be defined and validated?

- How will it be funded?

Answers to these require thoughtful discussion. They require independent judgement. They require insight from organizations outside healthcare whose experiences are instructive. They require fresh thinking.

Until and unless healthcare leaders recognize the imperative for transformational change, the system will calcify its victim-mindset and each sector will fend for itself with diminishing results. No sector—hospitals, insurers, drug companies, physicians—has all the answers and every sector faces enormous headwinds. Perhaps it’s time for a cross-sector coalition to step up with transformational change as the goal and the public’s well-being the moral compass.

PS: Last week, I caught up with Drs. Steve and Pat Gabbe in Columbus, Ohio. Having served alongside them at Vanderbilt and now as an observer of their work at Ohio State, I am reminded of the goodness and integrity of those in healthcare who devote their lives to meaningful, worthwhile work. Steve “burns with a clear blue flame” as a clinician, mentor and educator. Pat is the curator of a program, Moms2B, that seeks to alleviate Black-White disparities in infant mortality and maternal child health in Ohio. They’re great people who see purpose in their calling; they’re what make this industry worth fixing!

The Politics of Health Care and the 2024 Election

Introduction

Health policy and politics are inextricably linked. Policy is about what the government can do to shift the financing, delivery, and quality of health care, so who controls the government has the power to shape those policies.

Elections, therefore, always have consequences for the direction of health policy – who is the president and in control of the executive branch, which party has the majority in the House and the Senate with the ability to steer legislation, and who has control in state houses. When political power in Washington is divided, legislating on health care often comes to a standstill, though the president still has significant discretion over health policy through administrative actions. And, stalemates at the federal level often spur greater action by states.

Health care issues often, but not always, play a dominant role in political campaigns. Health care is a personal issue, so it often resonates with voters. The affordability of health care, in particular, is typically a top concern for voters, along with other pocketbook issues, And, at 17% of the economy, health care has many industry stakeholders who seek influence through lobbying and campaign contributions. At the same time, individual policy issues are rarely decisive in elections.

Health Reform in Elections

Copy link to Health Reform in Elections

Health “reform” – a somewhat squishy term generally understood to mean proposals that significantly transform the financing, coverage, and delivery of health care – has a long history of playing a major role in elections.

Harry Truman campaigned on universal health insurance in 1948, but his plan went nowhere in the face of opposition from the American Medical Association and other groups. While falling short of universal coverage, the creation of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 under Lyndon Johnson dramatically reduced the number of uninsured people. President Johnson signed the Medicare and Medicaid legislation at the Truman Library in Missouri, with Truman himself looking on.

Later, Bill Clinton campaigned on health reform in 1992, and proposed the sweeping Health Security Act in the first year of his presidency. That plan went down to defeat in Congress amidst opposition from nearly all segments of the health care industry, and the controversy over it has been cited by many as a factor in Democrats losing control of both the House and the Senate in the 1994 midterm elections.

For many years after the defeat of the Clinton health plan, Democrats were hesitant to push major health reforms. Then, in the 2008 campaign, Barack Obama campaigned once again on health reform, and proposed a plan that eventually became the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA ultimately passed Congress in 2010 with only Democratic votes, after many twists and turns in the legislative process. The major provisions of the ACA were not slated to take effect until 2014, and opposition quickly galvanized against the requirement to have insurance or pay a tax penalty (the “individual mandate”) and in response to criticism that the legislation contained so-called “death panels” (which it did not). Republicans took control of the House and gained a substantial number of seats in the Senate during the 2010 midterm elections, fueled partly by opposition to the ACA.

The ACA took full effect in 2014, with millions gaining coverage, but more people viewed the law unfavorably than favorably, and repeal became a rallying cry for Republicans in the 2016 campaign. Following the election of Donald Trump, there was a high profile effort to repeal the law, which was ultimately defeated following a public backlash. The ACA repeal debate was a good example of the trade-offs inherent in all health policies. Republicans sought to reduce federal spending and regulation, but the result would have been fewer people covered and weakened protections for people with pre-existing conditions. KFF polling showed that the ACA repeal effort led to increased public support for the law, which persists today.

Health Care and the 2024 Election

Copy link to Health Care and the 2024 Election

The 2024 election presents the unusual occurrence of two candidates – current vice president Kamala Harris and former president Donald Trump – who have already served in the White House and have detailed records for comparison, as explained in this JAMA column. With President Joe Biden dropping out of the campaign, Harris inherits the record of the current administration, but has also begun to lay out an agenda of her own.

The Affordable Care Act (Obamacare)

Copy link to The Affordable Care Act (Obamacare)

While Trump failed as president to repeal the ACA, his administration did make significant changes to it, including repealing the individual mandate penalty, reducing federal funding for consumer assistance (navigators) by 84% and outreach by 90%, and expanding short-term insurance plans that can exclude coverage of preexisting conditions.

In a strange policy twist, the Trump administration ended payments to ACA insurers to compensate them for a requirement to provide reduced cost sharing for low-income patients, with Trump saying it would cause Obamacare to be “dead” and “gone.” But, insurers responded by increasing premiums, which in turn increased federal premium subsidies and federal spending, likely strengthening the ACA.

In the 2024 campaign, Trump has vowed several times to try again to repeal and replace the ACA, though not necessarily using those words, saying instead he would create a plan with “much better health care.”

Although the Trump administration never issued a detailed plan to replace the ACA, Trump’s budget proposals as president included plans to convert the ACA into a block grant to states, cap federal funding for Medicaid, and allow states to relax the ACA’s rules protecting people with preexisting conditions. Those plans, if enacted, would have reduced federal funding for health care by about $1 trillion over a decade.

In contrast, the Biden-Harris administration has reinvigorated the ACA by restoring funding for consumer assistance and outreach and by increasing premium subsidies to make coverage more affordable, resulting in record enrollment in ACA Marketplace plans and historically low uninsured rates. The increased premium subsidies are currently slated to expire at the end of 2025, so the next president will be instrumental in determining whether they get extended. Harris has vowed to extend the subsidies, while Trump has been silent on the issue.

Abortion and Reproductive Health

Copy link to Abortion and Reproductive Health

The health care issue most likely to figure prominently in the general election is abortion rights, with sharp contrasts between the presidential candidates and the potential to affect voter turnout. In all the states where voters have been asked to weigh in directly on abortion so far (California, Kansas, Kentucky, Michigan, Montana, Ohio, and Vermont), abortion rights have been upheld.

Trump paved the way for the US Supreme Court to overturn Roe v Wade by appointing judges and justices opposed to abortion rights. Trump recently said, “for 54 years they were trying to get Roe v Wade terminated, and I did it and I’m proud to have done it.” During the current campaign, Trump has said that abortion policy should now be left to the states.

As president, Trump had also cut off family planning funding to Planned Parenthood and other clinics that provide or refer for abortion services, but this policy was reversed by the Biden-Harris administration.

Harris supports codifying into federal the abortion access protections in Roe v Wade.

Addressing the High Price of Prescription Drugs and Health Care Services

Copy link to Addressing the High Price of Prescription Drugs and Health Care Services

Trump has often spotlighted the high price of prescription drugs, criticizing both the pharmaceutical industry and pharmacy benefit managers. Although he kept the issue of drug prices on the political agenda as president, in the end, his administration accomplished little to contain them.

The Trump administration created a demonstration program, capping monthly co-pays for insulin for some Medicare beneficiaries at $35. Late in his presidency, his administration issued a rule to tie Medicare reimbursement of certain physician-administered drugs to the prices paid in other countries, but it was blocked by the courts and never implemented. The Trump administration also issued regulations paving the way for states to import lower-priced drugs from Canada. The Biden-Harris administration has followed through on that idea and recently approved Florida’s plan to buy drugs from Canada, though barriers still remain to making it work in practice.

With Harris casting the tie-breaking vote in the Senate, President Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, far-reaching legislation that requires the federal government to negotiate the prices of certain drugs in Medicare, which was previously banned. The law also guarantees a $35 co-pay cap for insulin for all Medicare beneficiaries, and caps out-of-pocket retail drug costs for the first time in Medicare. Harris supports accelerating drug price negotiation to apply to more drugs, as well as extending the $35 cap on insulin copays and the cap on out-of-pocket drug costs to everyone outside of Medicare.

How Trump would approach drug price negotiations if elected is unclear. Trump supported federal negotiation of drug prices during his 2016 campaign, but he did not pursue the idea as president and opposed a Democratic price negotiation plan. During the current campaign, Trump said he “will tell big pharma that we will only pay the best price they offer to foreign nations,” claiming that he was the “only president in modern times who ever took on big pharma.”

Beyond drug prices, the Trump administration issued regulations requiring hospitals and health insurers to be transparent about prices, a policy that is still in place and attracts bipartisan support.

Future Outlook

Ultimately, irrespective of the issues that get debated during the campaign, the outcome of the 2024 election – who controls the White House and Congress – will have significant implications for the future direction of health care, as is almost always the case.

However, even with changes in party control of the federal government, only incremental movement to the left or the right is the norm. Sweeping changes in health policy, such as the creation of Medicare and Medicaid or passage of the ACA, are rare in the U.S. political system. Similarly, Medicare for All, which would even more fundamentally transform the financing and coverage of health care, faces long odds, particularly in the current political environment. This is the case even though most of the public favors Medicare for All, though attitudes shift significantly after hearing messages about its potential impacts.

Importantly, it’s politically difficult to take benefits away from people once they have them. That, and the fact that seniors are a strong voting bloc, has been why Social Security and Medicare have been considered political “third rails.” The ACA and Medicaid do not have quite the same sacrosanct status, but they may be close.

The Presidential Debate will Frustrate Healthcare Voters

Tomorrow night, the Presidential candidates square off in Philadelphia. Per polling from last week by the New York Times-Siena, NBC News-Wall Street Journal, Ipsos-ABC News and CBS News, the two head into the debate neck and neck in what is being called the “chaos election.”

Polls also show the economy, abortion and immigration are the issues of most concern to voters. And large majorities express dissatisfaction with the direction the country is heading and concern about their household finances.

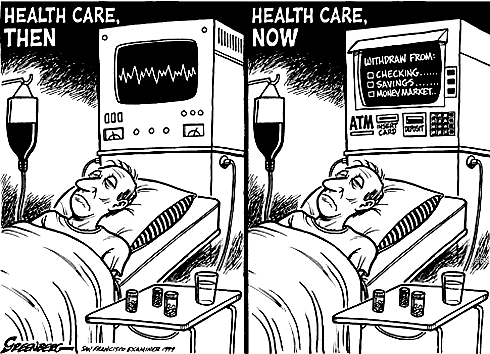

The healthcare system per se is not a major concern to voters this year, but its affordability is. Out-of-pocket costs for prescription drugs, insurance premiums and co-pays and deductibles for hospitals and physician services are considered unreasonable and inexplicably high. They contribute to public anxiety about their financial security alongside housing and food costs. And majorities think the government should do more by imposing price controls and limiting corporate consolidation.

That’s where we are heading into this debate. And here’s what we know for sure about the 90-minute production as it relates to health issues and policies:

- Each candidate will rail against healthcare prices, costs, and consolidation taking special aim at price gouging by drug companies and corporate monopolies that limit competition for consumers.

- Each will promise protections for abortion services: Trump will defer to states to arbitrate those rights while Harris will assert federal protection is necessary.

- Each will opine to the Affordable Care Act’s future: Trump will promise its repeal replacing it “with something better” and Harris will promise its protection and expansion.

- Each will promise increased access to behavioral health services as memories of last week’s 26-minute shooting tirade at Apalachee High School fade and the circumstances of Colt Gray’s mental collapse are studied.

- And each will promise adequate funding for their health priorities based on the effectiveness of their proposed economic plans for which specifics are unavailable.

That’s it in all likelihood. They’re unlikely to wade into root causes of declining life expectancy in the U.S. or the complicated supply-chain and workforce dynamics of the industry. And the moderators are unlikely to ask probative questions like these to discover the candidate’s forethought on matters of significant long-term gravity…

- What are the most important features of health systems in the world that deliver better results at lower costs to their citizens that could be effectively implemented in the U.S. system?

- How should the U.S. allocate its spending to improve the overall health and well-being of the entire population?

- How should the system be funded?

My take:

I will be watching along with an audience likely to exceed 60 million. Invariably, I will be frustrated by well-rehearsed “gotcha” lines used by each candidate to spark reaction from the other. And I will hope for more attention to healthcare and likely be disappointed.

Misinformation, disinformation and AI derived social media messaging are standard fare in winner-take-all politics.

When used in addressing health issues and policies, they’re effective because the public’s basic level of understanding of the health system is embarrassingly low: studies show 4 in 5 American’s confess to confusion citing the system’s complexity and, regrettably, the inadequacy of efforts to mitigate their ignorance is widely acknowledged.

Thus, terms like affordability, value, quality, not-for-profit healthcare and many others can be used liberally by politicians, trade groups and journalists without fear of challenge since they’re defined differently by every user.

Given the significance of healthcare to the economy (17.6% of the GDP),

the total workforce (18.6 million of the 164 million) and individual consumers and households (41% have outstanding medical debt and all fear financial ruin from surprise medical bills or an expensive health issue), it’s incumbent that health policy for the long-term sustainability of the health system be developed before the system collapses. The impetus for that effort must come from trade groups and policymakers willing to invest in meaningful deliberation.

The dust from this election cycle will settle for healthcare later this year and in early 2025. States are certain to play a bigger role in policymaking: the likely partisan impasse in Congress coupled with uncertainty about federal agency authority due to SCOTUS; Chevron ruling will disable major policy changes and leave much in limbo for the near-term.

Long-term, the system will proceed incrementally. Bigger players will fare OK and others will fail. I remain hopeful thoughtful leaders will address the near and long-term future with equal energy and attention.

Regrettably, the tyranny of the urgent owns the U.S. health system’s attention these days: its long-term destination is out-of-sight, out-of-mind to most. And the complexity of its short-term issues lend to magnification of misinformation, disinformation and public ignorance.

That’s why this debate will frustrate healthcare voters.

PS: Congress returns this week to tackle the October 1 deadline for passing 12 FY2025 appropriations bills thus avoiding a shutdown. It’s election season, so a continuing resolution to fund the government into 2025 will pass at the last minute so politicians can play partisan brinksmanship and enjoy media coverage through September. In the same period, the Fed will announce its much anticipated interest rate cut decision on the heals of growing fear of an economic slowdown. It’s a serious time for healthcare!

Quote of the Day – On Election Debate

Thought of the Day – What You Leave Behind

Pericles is perhaps best remembered for a building program centered on the Acropolis which included the Parthenon and for a funeral oration he gave early in the Peloponnesian War, as recorded by Thucydides. In the speech he honored the fallen and held up Athenian democracy as an example to the rest of Greece.

Are Employers Ready to Move from the Back Bench in U.S. Healthcare?

This year, 316 million Americans (92.3% of the population) have health insurance: 61 million are covered by Medicare, 79 million by Medicaid/CHIP and 164 million through employment-based coverage. By 2032, the Congressional Budget Office predicts Medicare coverage will increase 18%, Medicaid and CHIP by 0% and employer-based coverage will increase 3.0% to 169 million. For some in the industry, that justifies seating Medicare on the front row for attention. And, for many, it justifies leaving employers on the back bench since the working age population use hospitals, physicians and prescription meds less than seniors.

Last week, the Business Group on Health released its 2025 forecast for employer health costs based on responses from 125 primarily large employers surveyed in June: Highlights:

- “Since 2022, the projected increase in health care trend, before plan design changes, rose from 6% in 2022, 7.2% in 2024 to almost 8% for 2025. Even after plan design changes, actual health care costs continued to grow at a rate exceeding pre-pandemic increases. These increases point toward a more than 50% increase in health care cost since 2017. Moreover, this health care inflation is expected to persist and, in light of the already high burden of medical costs on the plan and employees, employers are preparing to absorb much of the increase as they have done in recent years.”.

- Per BGH, the estimated total cost of care per employee in 2024 is $18,639, up $1,438 from 2023. The estimated out-of-pocket cost for employees in 2024 is $1,825 (9.8%), compared to $1,831 (10.6%) in 2023.

The prior week, global benefits firm Aon released its 2025 assessment based on data from 950 employers:

- “The average cost of employer-sponsored health care coverage in the U.S. is expected to increase 9.0% surpassing $16,000 per employee in 2025–higher than the 6.4% increase to health care budgets that employers experienced from 2023 to 2024 after cost savings strategies. “

- On average, the total health-plan cost for employers increased 5.8% to $14,823 per employee from 2023 to 2024: employer costs increased 6.4% to 80.7% of total while employee premiums increased 3.4% increase–both higher than averages from the prior five years, when employer budgets grew an average of 4.4% per year and employees averaged 1.2% per year.

- Employee contributions in 2024 were $4,858 for health care coverage, of which $2,867 is paid in the form of premiums from pay checks and $1,991 is paid through plan design features such as deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance.

- The rate of health care cost increases varies by industry: technology and communications industry have the highest average employer cost increase at 7.4%, while the public sector has the highest average employee cost increase at 6.7%. The health care industry has the lowest average change in employee contributions, with no material change from 2023: +5.8%

And in July, PWC’s Health Research Institute released its forecast based on interviews with 20 health plan actuaries. Highlights:

- “PwC’s Health Research Institute (HRI) is projecting an 8% year-on-year medical cost trend in 2025 for the Group market and 7.5% for the Individual market. This near-record trend is driven by inflationary pressure, prescription drug spending and behavioral health utilization. The same inflationary pressure the healthcare industry has felt since 2022 is expected to persist into 2025, as providers look for margin growth and work to recoup rising operating expenses through health plan contracts. The costs of GLP-1 drugs are on a rising trajectory that impacts overall medical costs. Innovation in prescription drugs for chronic conditions and increasing use of behavioral health services are reaching a tipping point that will likely drive further cost inflation.”

Despite different methodologies, all three analyses conclude that employer health costs next year will increase 8-9%– well-above the Congressional Budget Office’ 2025 projected inflation rate (2.2%), GDP growth (2.4% and wage growth (2.0%). And it’s the largest one-year increase since 2017 coming at a delicate time for employers worried already about interest rates, workforce availability and the political landscape.

For employers, the playbook has been relatively straightforward: control health costs through benefits designs that drive smarter purchases and eliminate unnecessary services. Narrow networks, price transparency, on-site/near-site primary care, restrictive formularies, value-based design, risk-sharing contracts with insurers and more have become staples for employers.

But this playbook is not working for employers: the intrinsic economics of supply-driven demand and its regulated protections mitigate otherwise effective ways to lower their costs while improving care for their employees and families.

My take:

Last week, I reviewed the healthcare advocacy platforms for the leading trade groups that represent employers in DC and statehouses to see what they’re saying about their take on the healthcare industry and how they’re leaning on employee health benefits. My review included the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, National Federal of Independent Businesses, Business Roundtable, National Alliance of Purchaser Coalitions, Purchaser Business Group on Health, American Benefits Council, Self-Insurance Institute of America and the National Association of Manufacturers.

What I found was amazing unanimity around 6 themes:

- Providing health benefits to employees is important to employers. Protecting their tax exemptions, opposing government mandates, and advocating against disruptive regulations that constrain employer-employee relationships are key.

- Healthcare affordability is an issue to employers and to their employees, All see increasing insurance premiums, benefits design changes, surprise bills, opaque pricing, and employee out-of-pocket cost obligations as problems.

- All believe their members unwillingly subsidize the system paying 1.6-2.5 times more than what Medicare pays for the same services. They think the majority of profits made by drug companies, hospitals, physicians, device makers and insurers are the direct result of their overpayments and price gauging.

- All think the system is wasteful, inefficient and self-serving. Profits in healthcare are protected by regulatory protections that disable competition and consumer choices.

- All think fee-for-service incentives should be replaced by value-based purchasing.

- And all are worried about the obesity epidemic (123 million Americans) and its costs-especially the high-priced drugs used in its treatment. It’s the near and present danger on every employer’s list of concerns.

This consensus among employers and their advocates is a force to be reckoned. It is not the same voice as health insurers: their complicity in the system’s issues of affordability and accountability is recognized by employers. Nor is it a voice of revolution: transformational changes employers seek are fixes to a private system involving incentives, price transparency, competition, consumerism and more.

Employers have been seated on healthcare’s back bench since the birth of the Medicare and Medicaid programs in 1965. Congress argues about Medicare and Medicaid funding and its use. Hospitals complain about Medicare underpayments while marking up what’s charged employers to make up the difference. Drug companies use a complicated scheme of patents, approvals and distribution schemes to price their products at will presuming employers will go along. Employers watched but from the back row.

As a new administration is seated in the White House next year regardless of the winner, what’s certain is healthcare will get more attention, and alongside the role played by employers. Inequities based on income, age and location in the current employer-sponsored system will be exposed. The epidemic of obesity and un-attended demand for mental health will be addressed early on. Concepts of competition, consumer choice, value and price transparency will be re-defined and refreshed. And employers will be on the front row to make sure they are.

For employers, it’s crunch time: managing through the pandemic presented unusual challenges but the biggest is ahead. Of the 18 benefits accounted as part of total compensation, employee health insurance coverage is one of the 3 most expensive (along with paid leave and Social Security) and is the fastest growing cost for employers. Little wonder, employers are moving from the back bench to the front row.

Two less-obvious ways the Fed made mortgages pricier

Data: Federal Reserve; Chart: Axios Visuals

The Federal Reserve has pushed mortgage rates higher not just through its much-discussed interest rate policy decisions, but through two less widely understood channels, a new paper argues.

Why it matters:

Since 2022, high mortgage rates have made homebuying an expensive endeavor for would-be borrowers and created dysfunction in the housing market.

The big picture:

But mortgage rates have risen substantially higher than justified by the Fed’s rate hikes alone. That’s thanks in part to a double whammy of two other factors:

- Quantitative tightening has meant the Fed withdrawing billions from the mortgage market.

- Higher rates have led banks to do the same as they have lost deposits, says the paper presented by New York University economist Philipp Schnabl on Saturday at the Kansas City Fed’s annual symposium in Jackson Hole, Wyoming.

How it works:

As the Fed looked to stimulate the economy at the onset of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, it began buying mortgage-backed securities (MBS) on massive scale as part of its quantitative easing program, essentially funneling cash to homebuyers. Its stockpile of MBS rose from $1.4 trillion in March 2020 to $2.7 trillion at the peak.

- Its reversal, part of the Fed’s fight against inflation, has so far drained those holdings by about $400 billion.

- Meanwhile, in 2021, consumers’ rapid accumulation of pandemic savings swelled bank deposits, and banks — needing to deploy those funds — ramped up their own mortgage lending and purchases of MBS. But as rates rose, deposits reversed as depositors had better options in Treasury bills and money market mutual funds.

The intrigue:

As the Fed tightened policy to fight inflation starting in 2022, it raised its short-term interest rate target, which also led longer-term Treasury bond yields to rise. But the mortgage rates available to consumers rose by even more.

- The spread between the 10-year Treasury yield and average consumer mortgage rate was a mere 1.5% in May 2021, but nearly twice as large, 2.9%, in 2023.

- In other words, homebuyers got hit harder by monetary tightening than the U.S. government. The new paper helps explain why.

What they’re saying:

“Banks and the Fed bought enormous quantities of mortgages during 2020–21, causing mortgage rates to decline drastically,” write the authors, Itamar Drechsler, Alexi Savov, Schnabl and Dominik Supera.

- “When monetary policy reversed course, banks and the Fed cut back their mortgage holdings, causing mortgage rates to rise and the mortgage spread to widen,” they write. “Monetary policy thus had an outsized impact on mortgage rates.”

The hospital finance misconception plaguing C-suites

Health systems have a big challenge: rising costs and reimbursement that doesn’t keep up with inflation. The amount spent on healthcare annually continues to rise while outcomes aren’t meaningfully better.

Some people outside of the industry wonder: Why doesn’t healthcare just act more like other businesses?

“There seems to be a widely held belief that healthcare providers respond the same as all other businesses that face rising costs,” said Cliff Megerian, MD, CEO of University Hospitals in Cleveland. “That is absolutely not true. Unlike other businesses, hospitals and health systems cannot simply adjust prices in response to inflation due to pre-negotiated rates and government mandated pay structures. Instead, we are continually innovating approaches to population health, efficiency and cost management, ensuring that we maintain delivery of high quality care to our patients.”

Nonprofit hospitals are also responsible for serving all patients regardless of ability to pay, and University Hospitals is among the health systems distinguished as a best regional hospital for equitable access to care by U.S. News & World Report.

“This commitment necessitates additional efforts to ensure equitable access to healthcare services, which inherently also changes our payer mix by design,” said Dr. Megerian. “Serving an under-resourced patient base, including a significant number of Medicaid, underinsured and uninsured individuals, requires us to balance financial constraints with our ethical obligations to provide the highest quality care to everyone.”

Hospitals need adequate reimbursement to continue providing services while also staffing the hospital appropriately. Many hospitals and health systems have been in tense negotiations with insurers in the last 24 months for increased pay rates to cover rising costs.

“Without appropriate adjustments, nonprofit healthcare providers may struggle to maintain the high standards of care that patients deserve, especially when serving vulnerable populations,” said Dr. Megerian. “Ensuring fair reimbursement rates supports our nonprofit industry’s aim to deliver equitable, high quality healthcare to all while preserving the integrity of our health systems.”

Industry outsiders often seek free market dynamics in healthcare as the “fix” for an expensive and complicated system. But leaving healthcare up to the normal ebbs and flows of businesses would exclude a large portion of the population from services. Competition may lead to service cuts and hospital closures as well, which devastates communities.

“A misconception is that the marketplace and utilization of competitive business model will fix all that ails the American healthcare system,”

said Scot Nygaard, MD, COO of Lee Health in Ft. Myers and Cape Coral, Fla.

“Is healthcare really a marketplace, in which the forces of competition will solve for many of the complex problems we face, such as healthcare disparities, cost effective care, more uniform and predictive quality and safety outcomes, mental health access, professional caregiver workforce supply?”

Without comprehensive reform at the state or federal level, many health systems have been left to make small changes hoping to yield different results. But, Dr. Nygaard said, the “evidence year after year suggests that this approach is not successful and yet we fear major reform despite the outcomes.”

The dearth of outside companies trying to enter the healthcare space hasn’t helped. People now expect healthcare providers to function like Amazon or Walmart without understanding the unique complexities of the industry.

“Unlike retail, healthcare involves navigating intricate regulations, providing deeply personal patient interactions and building sustained trust,” said Andreia de Lima, MD, chief medical officer of Cayuga Health System in Ithaca, N.Y. “Even giants like Walmart found it challenging to make primary care profitable due to high operating costs and complex reimbursement systems. Success in healthcare requires more than efficiency; it demands a deep understanding of patient care, ethical standards and the unpredictable nature of human health.”

So what can be done?

Tracea Saraliev, a board member for Dominican Hospital Santa Cruz (Calif.) and PIH Health said leaders need to increase efforts to simplify and improve healthcare economics.

“Despite increased ownership of healthcare by consumers, the economics of healthcare remain largely misunderstood,” said Ms. Saraliev. “For example, consumers erroneously believe that they always pay less for care with health insurance. However, a patient can pay more for healthcare with insurance than without as a result of the negotiated arrangements hospitals have with insurance companies and the deductibles of their policy.”

There is also a variation in cost based on the provider, and even with financial transparency it’s a challenge to provide an accurate assessment for the cost of care before services. Global pricing and other value-based care methods streamline the price, but healthcare providers need great data to benefit from the arrangements.

Based on payer mix, geographic location and contracted reimbursement rates, some health systems are able to thrive while others struggle to stay afloat. The variation mystifies some people outside of the industry.

“Healthcare economics very much remains paradoxical to even the most savvy of consumers,” said Ms. Saraliev.

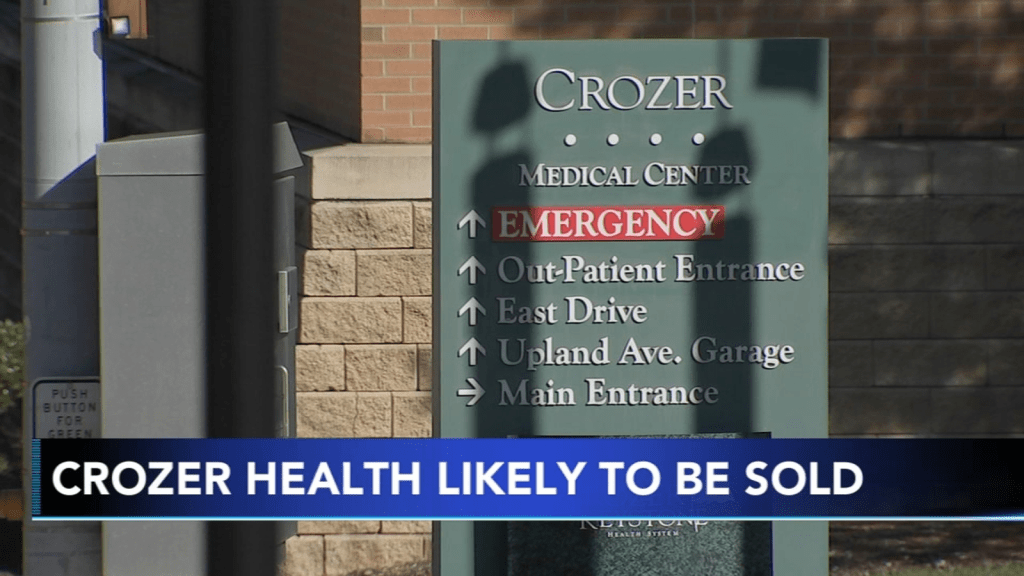

Senator urges Pennsylvania AG to intervene in Crozer sale

Pennsylvania state Sen. Tim Kearney has raised concerns about the lack of transparency and details around the planned sale of Upland, Pa.-based Crozer Health and has called on the state attorney general to step in and conduct a thorough analysis of the deal, the Daily Times reported Aug. 22.

Earlier this month, Los Angeles-based Prospect Medical Holdings and CHA Partners signed a letter of intent for CHA to acquire Crozer. The proposed deal would involve transitioning Crozer’s four hospitals back to nonprofit status.

“Prospect’s proposed sale of Crozer to CHA Partners LLC exemplifies the need for state oversight of hospital sales, as both entities appear to have histories of burning public partners despite demanding hefty subsidies,” Mr. Kearney said in a statement shared with Becker’s.

Unlike many other states, Pennsylvania’s Attorney General lacks statutory authority to deeply evaluate these deals, according to Mr. Kearney.

“While the AG’s legal settlement with Prospect gives them some oversight of this deal, the legislature needs to provide the AG with greater authority to protect hospitals and the communities that depend on them,” he said. “If the choice is CHA or closure, then we need some assurances that they will be a responsible organization and not just a profiteering speculator.”

Prospect, a for-profit company, plans to sell nine of its 16 hospitals in Pennsylvania, Rhode Island and Connecticut and is also being investigated by the Justice Department for alleged violations of the False Claims Act. A spokesperson for Prospect told Becker’s the system will continue to cooperate with the investigation, but feels that the allegations have no merit.

CHA did not respond to Becker’s request for comment.