Last Monday, CMS announced the base payment rate it will pay Medicare Advantage plans in 2025: plans will see an average 3.7%, or $16 billion, increase in payments once risk scores are factored in but a cut to base payments of 0.16% since 2025 risk scores were expected to be 3.86%. That’s the math.

It came as a surprise to insurers and investors who had imagined CMS would modify its November proposed rule to increase payments as has been the precedent in prior years. Per Bloomberg:

Then on Wednesday, CMS released a 1327-page final rule with sweeping directives about how Medicare Advantage plans should operate starting next year:

“This final rule will revise the Medicare Advantage (Part C), Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit (Part D), Medicare cost plan, and Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) regulations to implement changes related to Star Ratings, marketing and communications, agent/broker compensation, health equity, dual eligible special needs plans (D-SNPs), utilization management, network adequacy, and other programmatic areas. This final rule also codifies existing sub-regulatory guidance in the Part C and Part D programs.”

When first proposed in November, insurers pushed back. In response, most of the 3463 comment letters received by CMS said they needed more time to modify their plans. CMS replied: “We appreciate the commenter’s concern regarding the plans having enough time to understand the impact of finalized regulations. We will take their recommendation into consideration for future rulemaking.” P20). Accordingly, all MA plans must get approvals from CMS reflecting these changes on or before June 3, 2024.

Arguably, CMS took this hardline approach because bona fide studies by MedPAC, USC Shaeffer and others found widespread risk-score upcoding by Medicare Advantage plans that resulted in 6%-20% annual overpayments by Medicare.

Recent high-profile missteps by two of the biggest and most profitable MA players no doubt reinforced CMS’ get tougher posture: UnitedHealth Group’s Change Healthcare cybersecurity breech and Cigna’s $172 million Fraud and Abuse penalty for inflating its MA risk coding.

So, the transition from Medicare Advantage circa 2024 to Medicare Advantage 2025 will be its most significant since Medicare Choice was included in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. In 2024, Medicare Advantage experienced enrollment growth and profitability to which its players were accustomed despite a late-year spike in utilization:

- 33.8 million Medicare enrollees (or 51% of total Medicare enrollment) get their coverage from Medicare Advantage plans—up 6.4% from 2023.

- The average Medicare beneficiary has access to 43 Medicare Advantage plans in 2024, the same as in 2023, but more than double the number of plans offered in 2018. The majority of options do not require an extra payment above what Medicare pays private issuers on their behalf and the majority offer supplemental benefits including dental, eyecare, wellness et al.

- And Medicare Advantage insurers entered the year on solid financial footing: the biggest issuers posted strong profits in 2023 i.e. UnitedHealth Group: $22.4 billion, CVS (Aetna) Health: $8.3 billion, Elevance Health: $6 billion, Cigna Group: $5.2 billion, Centene: $2.7 billion, Humana: $2.5 billion

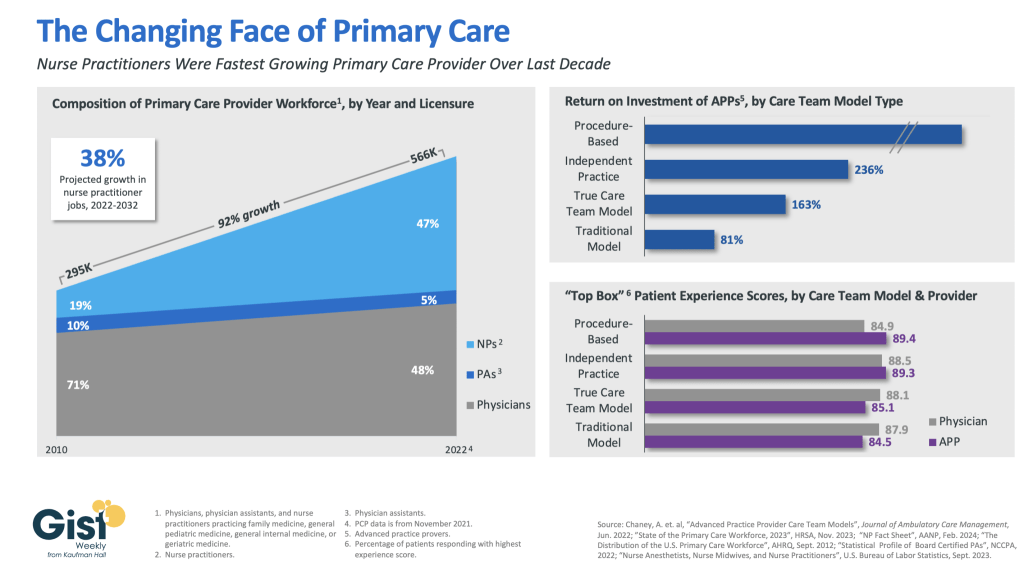

- In 4Q 2023, pent-up demand for services by Medicare Advantage enrollees pushed utilization of doctors, hospitals and other providers up 8.1% above prior year levels including 4Q 2023 increases for outpatient surgery 14.4%, outpatient visits excluding ER and surgery 8.7%, physician visits 6.0%, inpatient adult care 5.3%, Part B drugs 5% and ER visits 4%.

But 2025 will be different. The 4Q spike in utilization and impact of the new rules will have profound impact on Medicare Advantage: the biggest players like United and Humana will adapt and be OK, but others downstream will be disrupted or impaired:

- Smaller MA plan sponsors and their lobbyists: AHIP, ACHP, BCBSA, Better Medicare Alliance and the army of lobbyists deployed to defeat these rules took a hit. Members pay dues for results. These rules were disappointing (though it could have been worse).

- MA brokers, agents and marketing organizations: The limits on compensation, constraints on MA marketing tactics and enrollee protections around transparency may reduce revenues for many third-party marketing organizations that sell their services to the plans. A shakeout is likely.

- Supplemental services providers: lower payments by CMS will force some to reduce/eliminate supplemental benefits that are valued less by enrollees. Dental and prescription drug benefits appear safe but others (i.e. fitness programs) might be cut by some.

- Hospitals and physicians: Cuts by CMS to MA plans will trickle-down as reimbursement cuts to direct providers of care. Hardest hit will be smaller and rural providers in communities with large MA enrollment.

- MA enrollees: Though the rule adds behavioral health benefits, data privacy protections and equity considerations in utilization management decisions by the plans, the likely impact of the rate cut is fewer plan options for enrollees and higher premiums. Margin compression for MA plans will hurt bigger plans who will adapt but incapacitate smaller plans unable to survive.

- The Presidential campaigns: MA sponsors must submit their proposed 2025 plans to CMS on or before June 3, 2024—in the midst of Campaign 2024. And open enrollment will begin in October as MA plans launch marketing for their newly-revised offerings. No doubt, the Campaigns will opine to Medicare security in their closing rhetoric recognizing MA covers more than half its enrollees.

My take:

These rules are a big deal. CMS appears poised to challenge the industry’s formidable strengths and force changes.

Together, these rules will disrupt day to day operations in every MA plan, intensify friction with providers over network design, coverage and reimbursement negotiations and confuse enrollees who might have to pay more or change plans.

Medicare Advantage remains a work-in-process. Stay tuned.