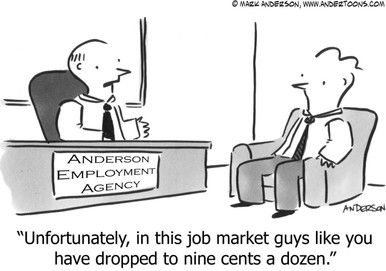

Nine states have told the Department of Labor they plan to ask for $36 billion in federal advances to cover the astronomical cost of unemployment payouts amid the coronavirus pandemic, according to new information provided to POLITICO Tuesday night by federal officials.

Illinois, which had fiscal problems before the coronavirus, tops the list with an $11 billion request in May and June.

California, the first state to borrow, plans to seek the next-highest amount over the same two months: $8 billion.

Texas will ask for advances totaling $6.4 billion in May, June and July and New York will ask for $4.4 billion in the same three months.

Connecticut, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Ohio and West Virginia have also signaled an intent to borrow between May and July to fund their unemployment systems. Some of the states, like Illinois and California, only requested advances for May and June.

There is no approval process for the advances, a department spokesperson said. States notify the Departments of Labor and Treasury of their needs, the spokesperson said, and the Department of Labor certifies those amounts to the Treasury Department.

States are able to draw down advances as they need them, but won’t necessarily end up using the full amounts.

California took out its first $348 million unemployment insurance loan last week, slipping into the red just two years after repaying the $65 billion it borrowed from the federal government during and after the Great Recession. It was one of about three dozen states that took out federal loans to weather the last downturn, a scenario likely to repeat itself in the coming weeks and months as unemployment numbers soar nationwide.

The latest national figures last week showed that more than 30 million had filed jobless claims since mid-March.

California’s unemployment insurance system, funded by payroll taxes, was barely solvent before the pandemic blindsided the economy, with less of a cushion than any other state or territory except for the U.S. Virgin Islands, according to the Department of Labor’s Trust Fund Solvency Report.

Besides Hawaii, all of the states requesting advances also fell well below the department’s recommended solvency level.

Since mid-March, California Gov. Gavin Newsom said Monday, the state has issued $7.8 billion in unemployment relief, and more than 4.1 million people have filed claims — about 21 percent of the state’s pre-pandemic workforce.

Newsom stressed that the state was “good for our word,” but called for direct federal aid. “This pandemic is bigger than even the state of California,” he said. “The economic consequences of this pandemic are such that we can balance our budgets without substantial cuts, unless we get additional federal support.”

States won’t accrue interest on these federal loans through Dec. 31, under the federal Families First Coronavirus Response Act. But the last round of unemployment fund borrowing cost California $1.4 billion in interest payments, according to the state’s Department of Finance.

CAMBRIDGE – Aristotle was right. Humans have never been atomized individuals, but rather social beings whose every decision affects other people. And now the COVID-19 pandemic is driving home this fundamental point: each of us is morally responsible for the infection risks we pose to others through our own behavior.

In fact, this pandemic is just one of many collective-action problems facing humankind, including climate change, catastrophic biodiversity loss, antimicrobial resistance, nuclear tensions fueled by escalating geopolitical uncertainty, and even potential threats such as a collision with an asteroid.

As the pandemic has demonstrated, however, it is not these existential dangers, but rather everyday economic activities, that reveal the collective, connected character of modern life beneath the individualist façade of rights and contracts.

Those of us in white-collar jobs who are able to work from home and swap sourdough tips are more dependent than we perhaps realized on previously invisible essential workers, such as hospital cleaners and medics, supermarket staff, parcel couriers, and telecoms technicians who maintain our connectivity.

Similarly, manufacturers of new essentials such as face masks and chemical reagents depend on imports from the other side of the world. And many people who are ill, self-isolating, or suddenly unemployed depend on the kindness of neighbors, friends, and strangers to get by.

The sudden stop to economic activity underscores a truth about the modern, interconnected economy: what affects some parts substantially affects the whole. This web of linkages is therefore a vulnerability when disrupted. But it is also a strength, because it shows once again how the division of labor makes everyone better off, exactly as Adam Smith pointed out over two centuries ago.

Today’s transformative digital technologies are dramatically increasing such social spillovers, and not only because they underpin sophisticated logistics networks and just-in-time supply chains. The very nature of the digital economy means that each of our individual choices will affect many other people.

Consider the question of data, which has become even more salient today because of the policy debate about whether digital contact-tracing apps can help the economy to emerge from lockdown faster.

This approach will be effective only if a high enough proportion of the population uses the same app and shares the data it gathers. And, as the Ada Lovelace Institute points out in a thoughtful report, that will depend on whether people regard the app as trustworthy and are sure that using it will help them. No app will be effective if people are unwilling to provide “their” data to governments rolling out the system. If I decide to withhold information about my movements and contacts, this would adversely affect everyone.

Yet, while much information certainly should remain private, data about individuals is only rarely “personal,” in the sense that it is only about them. Indeed, very little data with useful information content concerns a single individual; it is the context – whether population data, location, or the activities of others – that gives it value.

Most commentators recognize that privacy and trust must be balanced with the need to fill the huge gaps in our knowledge about COVID-19. But the balance is tipping toward the latter. In the current circumstances, the collective goal outweighs individual preferences.

But the current emergency is only an acute symptom of increasing interdependence. Underlying it is the steady shift from an economy in which the classical assumptions of diminishing or constant returns to scale hold true to one in which there are increasing returns to scale almost everywhere.

In the conventional framework, adding a unit of input (capital and labor) produces a smaller or (at best) the same increment to output. For an economy based on agriculture and manufacturing, this was a reasonable assumption.

But much of today’s economy is characterized by increasing returns, with bigger firms doing ever better. The network effects that drive the growth of digital platforms are one example of this. And because most sectors of the economy have high upfront costs, bigger producers face lower unit costs.

One important source of increasing returns is the extensive experience-based know-how needed in high-value activities such as software design, architecture, and advanced manufacturing. Such returns not only favor incumbents, but also mean that choices by individual producers and consumers have spillover effects on others.

The pervasiveness of increasing returns to scale, and spillovers more generally, has been surprisingly slow to influence policy choices, even though economists have been focusing on the phenomenon for many years now. The COVID-19 pandemic may make it harder to ignore.

Just as a spider’s web crumples when a few strands are broken, so the pandemic has highlighted the risks arising from our economic interdependence. And now California and Georgia, Germany and Italy, and China and the United States need each other to recover and rebuild. No one should waste time yearning for an unsustainable fantasy.