LIMA, Peru — The doctor watched the patients stream into his intensive care unit with a sense of dread.

For weeks, César Salomé, a physician in Lima’s Hospital Mongrut, had followed the chilling reports. A new coronavirus variant, spawned in the Amazon rainforest, had stormed Brazil and driven its health system to the brink of collapse. Now his patients, too, were arriving far sicker, their lungs saturated with disease, and dying within days. Even the young and healthy didn’t appear protected.

The new variant, he realized, was here.

“We used to have more time,” Salomé said. “Now, we have patients who come in and in a few days they’ve lost the use of their lungs.”

The P.1 variant, which packs a suite of mutations that makes it more transmissible and potentially more dangerous, is no longer just Brazil’s problem. It’s South America’s problem — and the world’s.

In recent weeks, it has been carried across rivers and over borders, evading restrictive measures meant to curb its advance to help fuel a coronavirus surge across the continent. There is mounting anxiety in parts of South America that P.1 could quickly become the dominant variant, transporting Brazil’s humanitarian disaster — patients languishing without care, a skyrocketing death toll — into their countries.

“It’s spreading,” said Julio Castro, a Venezuelan infectious-disease expert. “It’s impossible to stop.”

In Lima, scientists have detected the variant in 40 percent of coronavirus cases. In Uruguay, it’s been found in 30 percent. In Paraguay, officials say half of cases at the border with Brazil are P.1. Other South American countries — Colombia, Argentina, Venezuela, Chile — have discovered it in their territories. Limitations in genomic sequencing have made it difficult to know the variant’s true breadth, but it has been identified in more than two dozen countries, from Japan to the United States.

Hospital systems across South America are being pushed to their limits. Uruguay, one of South America’s wealthiest nations and a success story early in the pandemic, is barreling toward a medical system failure. Health officials say Peru is on the precipice, with only 84 intensive care beds left at the end of March. The intensive care system in Paraguay, roiled by protests last month over medical shortcomings, has run out of hospital beds.

“Paraguay has little chance of stopping the spread of the P.1 variant,” said Elena Candia Florentín, president of the Paraguayan Society of Infectious Diseases.

“With the medical system collapsed, medications and supplies chronically depleted, early detection deficient, contact tracing nonexistent, waiting patients begging for treatment on social media, insufficient vaccinations for health workers, and uncertainty over when general and vulnerable populations will be vaccinated, the outlook in Paraguay is dark,” she said.

How P.1 spread across the region is a distinctly South American story. Nearly every country on the continent shares a land border with Brazil. People converge on border towns, where crossing into another country can be as simple as crossing the street. Limited surveillance and border security have made the region a paradise for smugglers. But they have also made it nearly impossible to control the variant’s spread.

“We share 1,000 kilometers of dry border with Brazil, the biggest factory of variants in the world and the epicenter of the crisis,” said Gonzalo Moratorio, a Uruguayan molecular virologist tracking the variant’s growth. “And now it’s not just one country.”

The Brazilian city of Tabatinga, deep in the Amazon rainforest, where officials suspect the virus crossed into Colombia and Peru, is emblematic of the struggle to contain the variant. The city of 70,000 was swept by P.1 earlier this year. Many in the area have family ties in several countries and are accustomed to crossing borders with ease — canoeing across the Amazon River to Peru or walking into Colombia.

“People ended up bringing the virus from one side to the other,” said Sinesio Tikuna Trovão, an Indigenous leader. “The crossing was free, with both sides living right on top of one another.”

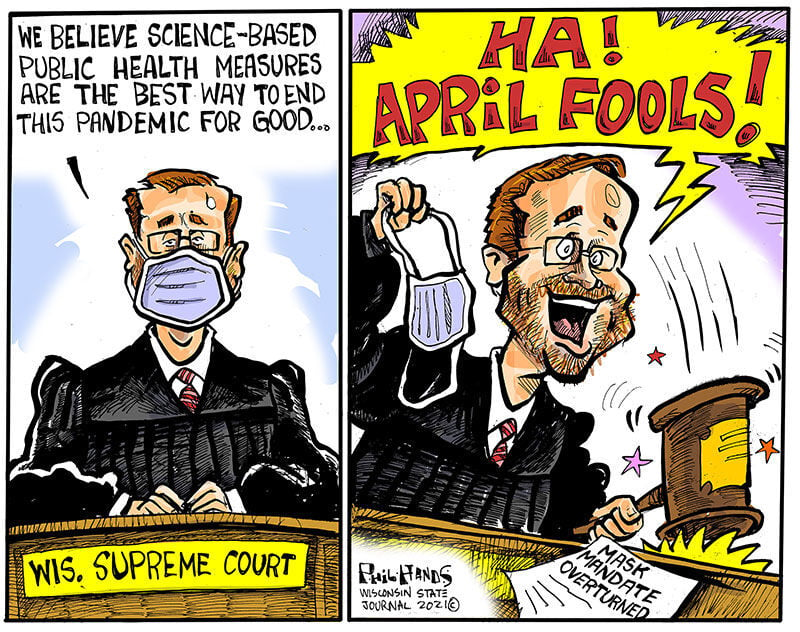

Now that the variant has infiltrated numerous countries, stopping its spread will be difficult. Most South American countries, with the exception of Brazil, adopted stringent containment measures last year. But they have been undone by poverty, apathy, distrust and exhaustion. With national economies battered and poverty rising sharply, public health experts fear more restrictions will be difficult to maintain. In Brazil, despite record death numbers, many states are lifting restrictions. (SOUND FAMILIAR)

That has left inoculation as the only way out. But coronavirus vaccines are South America’s white whale: often discussed, but rarely seen. The continent hasn’t distributed its own vaccine or negotiated a regional agreement with pharmaceutical companies. It’s one of the world’s hardest-hit regions but has administered only 6 percent of the world’s vaccine doses, according to the site Our World in Data. (The outlier is Chile, which is vaccinating residents more quickly than anywhere in the Americas — but still suffering a surge in cases.)

“We should not only blame the policy response,” said Luis Felipe López-Calva, the United Nations Development Program’s regional director for Latin America and the Caribbean. “We have to understand the vaccine market.”

“And there is a failure in the market,” he said.

The vaccine has become so scarce, López-Calva said, that officials are imposing restrictions on information. It’s nearly impossible to know how much governments are paying for doses. Some regional blocs, such as the African Union and the European Union, have negotiated joint contracts. But in South America, it has been every country for itself — diminishing the bargaining power for each one.

“This has been harmful for these countries, and for the whole world to stop the virus,” López-Calva said. “Because it’s never been more clear that no one is protected until everyone is protected.”

Paulo Buss, a prominent Brazilian scientist, said it didn’t have to be like this. He was Brazil’s health representative to the Union of South American Nations, which negotiated several regional deals with pharmaceutical companies before the coronavirus pandemic. But that union came apart amid political differences just before the arrival of the virus.

“It was the worst possible moment,” Buss said. “We’ve lost capacity and our negotiation attempts have been fragmented. Multi-lateralism was weakened.”

Vaccine scarcity has led to line-jumping scandals all over South America, but particularly in Peru. Hundreds of politically connected people, including cabinet ministers and former president Martín Vizcarra, snagged vaccine doses early. Now people are calling for criminal charges.

As officials bicker and the vaccination campaign is delayed, the variant continues to spread. P.1 accounts for 70 percent of cases in some parts of the Lima region, according to officials. Last week, the country logged the highest daily case count since August — more than 11,000. On Saturday, the country recorded 294 deaths, the most in a day since the start of the pandemic.

Peruvians have been stunned by how quickly the surge overwhelmed the health-care system. Public health analysts and government officials had believed Peru was prepared for a second wave. But it wasn’t ready for the variant.

“We did not expect such a strong second wave,” said Percy Mayta-Tristan, director of research at the Scientific University of the South in Lima. “The first wave was so extensive. The presence of the Brazilian variant helps explain why.”