As a warehouse manager at a Food 4 Less in Los Angeles, Norma Leiva greets delivery drivers hauling in soda and chips and oversees staff stocking shelves and helping customers. At night, she returns to the home she shares with her elderly mother-in-law, praying the coronavirus isn’t traveling inside her.

A medical miracle at the end of last year seemed to answer her prayers: Leiva, 51, thought she was near the front of the line to receive a vaccine, right after medical workers and people in nursing homes. Now that California has expanded eligibility to millions of older residents — in a bid to accelerate the administration of the vaccines — she is mystified about when it will be her turn.

“The latest I’ve heard is that we’ve been pushed back. One day I hear June, another mid-February,” said Leiva, whose sister, also in the grocery business, was sickened last year with the virus, which has pummeled Los Angeles County — the first U.S. county to record 1 million cases. “I want the elderly to get it because I know they’re in need of it, but we also need to get it, because we’re out there serving them. If we’re not healthy, our community’s not healthy.”

Delaying vaccinations for front-line workers, especially food and grocery workers, has stark consequences for communities of color disproportionately affected by the pandemic. “In the job we do,” Leiva said, “we are mostly Blacks and Hispanics.”

Many states are trying to speed up a delayed and often chaotic rollout of coronavirus vaccines by adding people 65 and older to near the front of the line. But that approach is pushing others back in the queue, especially because retired residents are more likely to have the time and resources to pursue hard-to-get appointments. As a result, workers who often face the highest risk of exposure to the virus will be waiting longer to get protected, according to experts, union officials and workers.

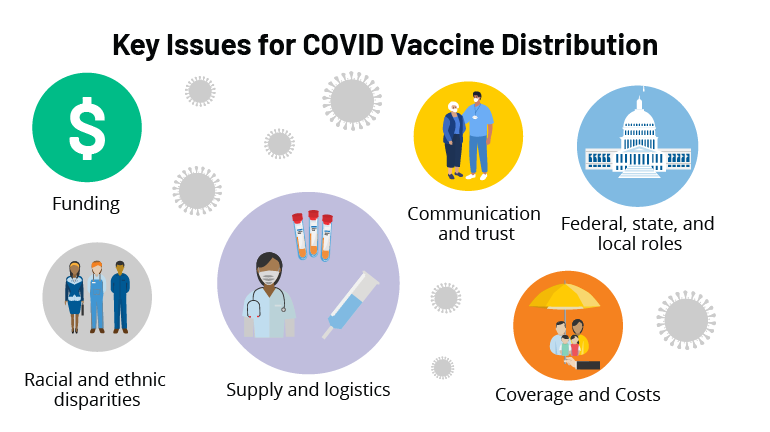

The shifting priorities illuminate political and moral dilemmas fundamental to the mass vaccination campaign: whether inoculations should be aimed at rectifying racial disparities, whether the federal government can apply uniform standards and whether local decision-making will emphasize more than ease of administration.

Speed has become all the more critical with the emergence of highly transmissible variants of the virus. Only by performing 3 million vaccinations a day — more than double the current rate — can the country stay ahead of the rapid spread of new variants, according to modeling conducted by Paul Romer, a Nobel Prize-winning economist.

But low-wage workers without access to sick leave are among those most likely to catch and transmit new variants, said Richard Besser, president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and former acting director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Because there are not enough doses of the vaccines to immunize front-line workers and everyone over 65, he said, officials should carefully weigh combating the pernicious effects of the virus on communities of color against the desire to expedite the rate of inoculation.

“If the obsession is over the number of people vaccinated,” Besser said, “we could end up vaccinating more people, while leaving those people at greatest risk exposed to ongoing rates of infection.”

The move to broaden vaccine availability to a wider swath of the elderly population — backed by Trump administration officials in their final days in office and members of President Biden’s health team — marks a departure from expert guidance set forth in December, as the vaccine rollout was getting underway.

A panel of experts advising the CDC recommended that the second priority group include front-line essential workers, along with adults 75 and older. The guidance represented a compromise between the desire to shield people most likely to catch and transmit the virus — because they cannot socially distance or work from home — and the effort to protect people most prone to serious complications and death.

People of color and immigrants are overrepresented not just in grocery jobs but also in meatpacking, public transit and corrections facilities, where outbreaks have taken a heavy toll. Black and Latino Americans are three to four timesmore likely than White people to be hospitalized and almost three times more likely to die of covid-19, the illness caused by the coronavirus, according to the CDC.

The desire to make vaccine administration equitable was central to recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.

“We cannot abandon equity because it’s hard to measure and it’s hard to do,” Grace Lee, a committee member and a pediatrics professor at Stanford University’s School of Medicine, said at the time.

On Wednesday at a committee meeting, Lee said officials need both efficiency and equity to “ensure that we are accountable for how we’re delivering vaccine.”

“Absolutely agree we do not want any doses in freezers or wasted in any way,” Lee said.

But efficiency has won out in most places.

Some state leaders, such as Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) and Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R), acted on their own, lowering the age threshold to 65 soon after distribution began last year. Others followed with the blessing of top federal officials.

Biden’s advisers have said equity will be central to their efforts, calling access in underserved communities a “moral imperative” and promising, in a national vaccination strategy document, “we remain focused on building programs to meet the needs of hard-to-reach and high-risk populations.” In the meantime, they have similarly encouraged states to broaden vaccine availability to a larger segment of their older populations without providing guidance about how to ensure front-line workers remain a priority.

Experts studying health disparities say prioritizing people over 65 disproportionately favors White people, because people of color, especially Black men, tend to die younger, owing to racism’s effect on physical health. Twenty percent of White people are 65 or over, while just 9 percent of people of color are in that age group, according to federal figures.

“People are thinking about risk at an individual level as opposed to at a structural level. People are not understanding that where you work and where you live can actually bring more risks than your age,” said Camara Phyllis Jones, a family physician, epidemiologist and past president of the American Public Health Association. “It’s worse than I thought.”

The constantly changing priorities have made the uneven rollout all the more difficult to navigate. There is confusion over when, where and how to get shots, with different jurisdictions taking different approaches in an illustration of the nation’s decentralized public health system.

While praising the effort to expand access and speed up the administration of shots, Marc Perrone, president of the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, said increasing reliance on age-based eligibility “must not come at the expense of the essential workers helping families put food on the table during this crisis.

“Public health officials must work with governors in all 50 states to end the delays and act swiftly to distribute the vaccine to grocery and meatpacking workers on the front lines, before even more get sick and die,” he said.

Mary Kay Henry, president of the Service Employees International Union, said the only way to ensure front-line workers get the vaccines they need is to involve them and their union representatives in decisions about eligibility and access. Unions, she said, could also be tapped to conduct outreach in hard-to-reach communities, including those not conversant in English.

“Essential workers who’ve been on the front lines both in health care but also across the service and care sectors — child care, airline, janitorial, security — face extraordinary risk,” she said.

Leiva, a 33-year member of UFCW Local 770, said the celebration of essential workers should come with recognition of their sacrifice, which is unevenly felt across racial groups. When the virus tore through the grocery store, she said, “every single one of them in that cluster was Hispanic.”

But with hospitals dangerously full in recent weeks, and less than half of distributed vaccine doses administered, many states broadened their top priority groups to include older adults, hoping to lessen the burden on hospitals and expedite vaccine administration.

Protecting people 65 and older, officials say, saves the lives of those who face the gravest consequences and reduces the stress on intensive care units. Risk for severe covid-19 illness increases with age; 8 out of 10 deaths reported in the United States have been in people 65 and older.

Older people in the United States have also encountered enormous hurdles in gaining access to the vaccines. Faced with overloaded sign-up websites and jammed phone lines, they have sometimes spent nights waiting in line.

In more than half the states — at least 28, by one count — people 65 and older are in the top two priority groups, behind health-care workers and residents in long-term care facilities. As a result, front-line workers either fall behind the older group or are squeezed into the same pool, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis.

“When you make that pool of eligible people much bigger, you’re creating much longer wait times for some of these groups,” said Jennifer Kates, a senior vice president at the foundation.

Front-line workers often labor in crowded conditions. Some live in multigenerational households. By contrast, many older adults are retired, have greater access to sign-up portals and have more time to wait in lines outside of clinics, health officials said.

“The 65-year-old person who is wealthier and can stay home and isn’t working and is retired and can ride it out for another two months … is less likely to get infected than the person who has to go outside every day for work,” said Roberto B. Vargas, assistant dean for health policy at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Los Angeles.

In California, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) announced Jan. 13 that the state was “significantly increasing our efforts to get these vaccines administered, get them out of freezers and get them into people’s arms” by increasing the number of people eligible to receive shots. “Everybody 65 and over — about 6.6 million Californians — we are now pulling into the tier to make available vaccines.”

On Jan. 25, Newsom said the state would move to an age-based eligibility system after vaccinating those now at the front of the line, including health-care workers, food and agriculture workers, teachers, emergency personnel and seniors 65 and older.

The abrupt changes confused local health officials.

Julie Vaishampayan, public health officer in San Joaquin Valley’s Stanislaus County, said the county had just finished vaccinating health-care workers and was getting ready to reach out to farm laborers at a tomato-packing company and food-processing workers. When the state added those 65 and older, the county had to pivot abruptly,as it faced a quintessential supply-and-demand dilemma.

“There isn’t enough vaccine to do it all, so how do we balance?” she said in an email. “This is really hard.”

In Tennessee, teachers were initially promised access but then were told to wait until people 70 and older got their shots. The state’s health commissioner, Lisa Piercey, said she was moving more gradually through the age gradations so as not to crowd out workers, treating the federal framework as guidance, which is often how officials have characterized it. “It’s not an either/or situation,” she said in an interview this month.

But with vaccine supply sharply limited, priorities had to be narrowed. By vaccinating older residents, she said, the state was also protecting its medical infrastructure by reducing the likelihood that older people, who are more likely to be hospitalized, would fall ill. Once there is more supply, she said, she would be able to amplify aspects of the state’s planning geared toward underserved and hard-to-reach populations. “I can’t wait to manifest that equity plan.”

In Nebraska, the health department in Douglas County, which includes Omaha, prioritized older residents over “critical industry workers who can’t work remotely” after the state expanded eligibility to residents 65 and older, according to a January news release. Meatpacking workers, grocery store employees, teachers and public transit workers were bumped lower in line.

Omaha’s teachers union had wanted its approximately 4,100 members to get shots before the district resumes full-time, in-person instruction for elementary and middle school students Tuesday. Now, they must wait until late spring, said Robert Miller, president of the Omaha Education Association.

“The fear, it goes hand in glove with going back to school five days a week,” he said, despite CDC reports that schools operating in person have seen scant transmission. “We’ve had some teachers who have multigenerational homes, who live in the basement, … and they can’t interact with their parents. We have some teachers who are staying at a different apartment away from their elder loved ones.”

Some state leaders sought to defend broadening eligibility to more of the elderly population, saying it was consistent with efforts to address racial disparities. Illinois had reduced the age requirement to 65, Gov. J.B. Pritzker (D) said recently, “in order to reduce covid-19 mortality and limit community spread in Black and Brown communities.” His office did not respond to a request for comment about how lowering the age threshold would have that effect.

In Massachusetts, state leaders announced Jan. 25 that people 65 and older and those with at least two high-risk medical conditions were next in line, ahead of educators and workers in transit, utility, food and agriculture, sanitation, and public works and public health.

That means Dorothy Williams, who runs a day-care center in a predominantly Black community where the infection rate is among the highest in Boston, has to wait. Her center stayed open throughout the pandemic, caring for children of essential workers, many of them in low-wage jobs in hospitals or nursing homes.

She recognizes the long hours and the exposure risks of those health-care aides. That means “we’re exposed,” she said, “each and every single day.” She has been able to keep the coronavirus at bay, but two weeks ago, she had a scare that forced her to close and get everyone tested after a child became ill. The tests came back negative, but the fear remains.

“We are at risk,” she said.

:format(webp)/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/67131793/GettyImages_1254708529.0.jpg)