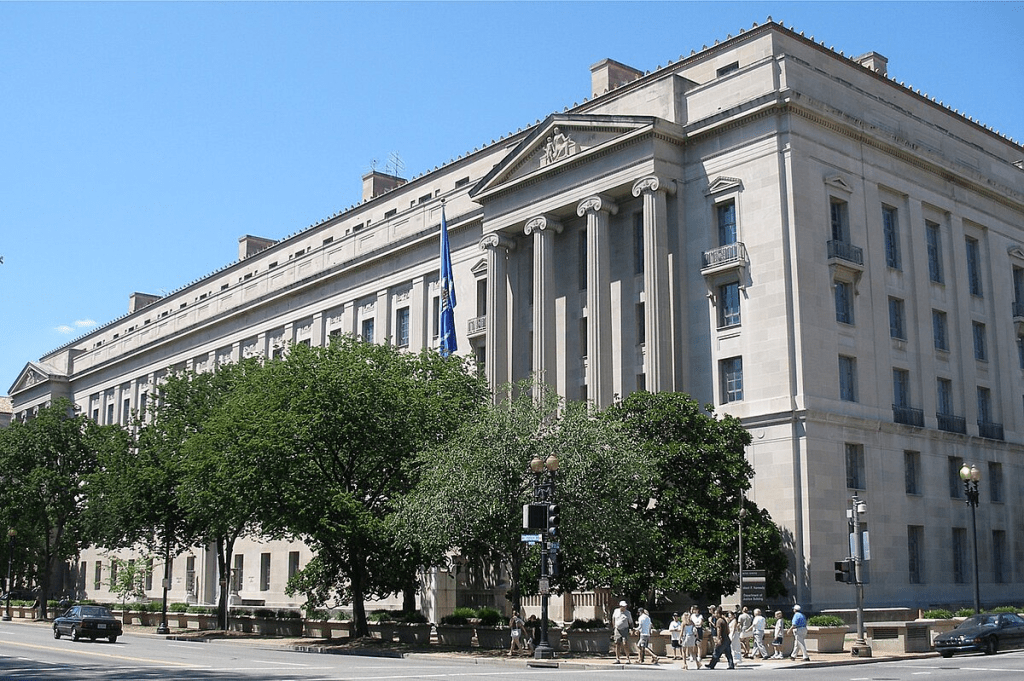

I’ve been at this for so long and have seen so much. And it’s hard to overstate how significant the latest revelations from The Wall Street Journal are. According to its reporting, the U.S. Department of Justice’s criminal health care-fraud unit is questioning former UnitedHealth Group employees about the company’s Medicare billing practices regarding how the company records diagnoses that trigger higher payments from taxpayers.

For years, independent policy experts and *some* regulators have warned that the private Medicare Advantage program has become a breeding ground for upcoding and tax dollar waste. The tactic being scrutinized by the DOJ is called “upcoding.” Essentially, Medicare Advantage companies have an incentive to “find” new illnesses — even among patients who might not need additional treatment because the more serious the diagnoses, the bigger the government payouts to the company.

According to the Journal, prosecutors, FBI agents, and the Health and Human Services Inspector General have been asking ex-employees about special training for doctors, software that flags profitable conditions, and even bonuses for physicians who recode patient files. One former UnitedHealth doctor told the Journal that prosecutors inquired about pressure to use certain diagnosis codes and bonus pay for certain health care decisions that financially favored UnitedHealth.

The Journal’s data shows that UnitedHealth’s members received certain lucrative diagnoses at higher rates than patients in other Medicare Advantage plans — billions of extra dollars that ultimately come from taxpayers. In one example, they reportedly pulled in about $2,700 more taxpayer dollars per patient visit when nurses went into seniors’ homes to hunt for additional conditions.

In a statement, UnitedHealth insists they “remain focused on what matters most: delivering better outcomes, more benefits, and lower costs for the people we serve.”

This latest criminal investigation joins at least two other DOJ probes into UnitedHealth’s billing and potential antitrust violations. And it’s yet another reminder that the Medicare Advantage program — which, much to many advocates alarm, now covers more than half of all Medicare enrollees – is desperately in need of real oversight.

If there’s any silver lining, it’s that courageous former employees are speaking up. They know what I know: This “profit-maximizing” through “upcoding” and “favorable selection” drains billions that could be better spent on actual patient care and pad Wall Street profits.