For many providers, 2023 provided a return to profitability (albeit at modest levels) following the devastating operating and investment losses experienced in 2022. Kaufman Hall’s National Hospital Flash Report data illustrated generally improving operating margins throughout the year, leveling off at 2.0% in November on a year-to-date basis.

This level of performance is commendable given 2022 and early 2023 margins, although it is still well below the 3% to 4% range which we believe is needed for long-term sustainability in the not-for-profit healthcare world. We may well have reached a point of stability with respect to operating performance, but at a lower level.

The question for hospital and health system leaders is whether this level of operating stability provides sustainability?

From stabilization to normalization

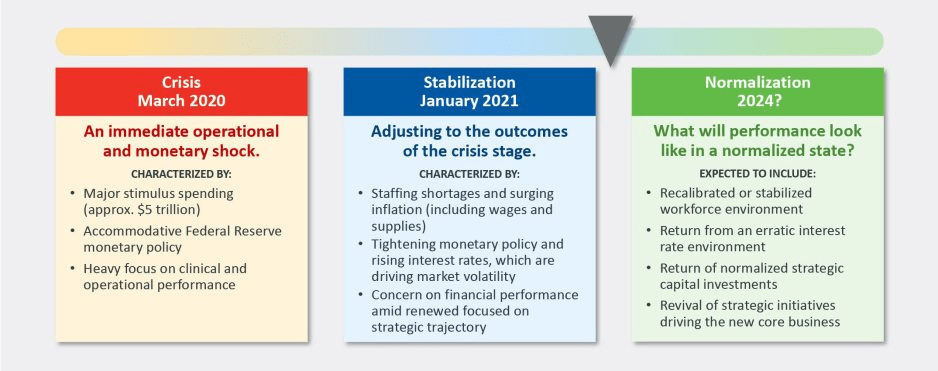

Since the pandemic began in 2020, the progress of recovery has been viewed over three phases: crisis, stabilization, and normalization. In last year’s outlook, we noted that we were in the midst of a potentially multi-year stabilization phase, which would continue to be marked with volatility—including ongoing labor market dislocations, inflationary pressures, and restrictive monetary policies. As we enter 2024, there are signs that we are now at the bridge between stabilization and normalization (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Three Phases of Recovery from the Covid Pandemic

“The question for hospital and health system leaders is whether that level of stability provides sustainability?”

These signs include evidence that the first two indicators for normalization—a recalibrated or stabilized workforce environment and a return from an erratic interest rate environment—are coming into place. In our 2023 State of Healthcare Performance Improvement survey, respondents indicated that the spike in contract labor utilization that has been a dominant factor in operating expense increases was subsiding. Sixty percent of respondents said that utilization of contract labor was decreasing, and 36% said it was holding steady. Only 4% noted an increase in contract labor usage. Overall employee cost inflation seems to be subsiding as well: for all three labor categories in our survey (clinical, administrative, and support services), more organizations were able to hold salary increases to the 0% – 5% range in 2023 than in 2022.

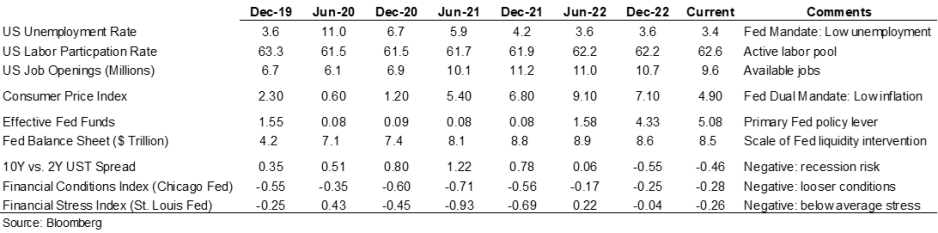

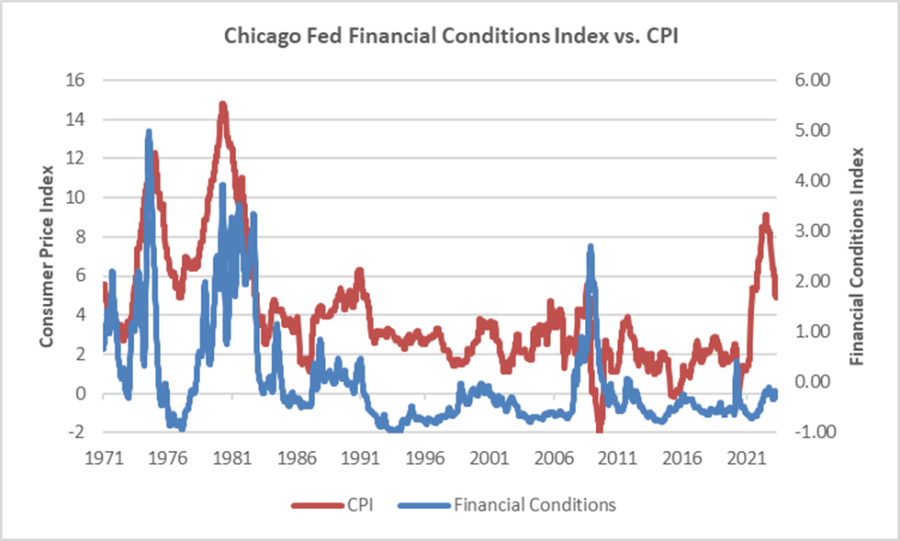

There is good news on the interest rate front as well. After a series of rate increases in 2023, the Federal Reserve has held steady the last six months and has signaled rate cuts in 2024. Inflation has cooled markedly (albeit not yet at target levels), and employment rates have held steady. The Fed may have achieved a “soft landing” that satisfies its dual mandate of stable prices and maximum sustainable employment. Borrowing costs for not-for-profit hospital issuers have declined nearly 100 basis points in the last two months and we are expecting a return to more normal issuance levels in the first half of 2024.

There are other indications of normalization, including in the rating agencies’ outlooks for 2024. Regardless of the headline, all saw significant improvement in healthcare performance 2023.

The final answer to the question of whether the healthcare industry is entering the normalization phase likely will hinge on the last two indicators. Will we see a return of normalized strategic capital investments, and will we see a revival of strategic initiatives driving the core business (perhaps newly imagined)?

In effect, are health care systems simply surviving or are they thriving?

Looking forward, several factors could either bolster or undermine healthcare leaders’ confidence and willingness to resume a more normal level of investment in both capital needs and strategic growth. These include:

- Politics and the 2024 elections. When North Carolina—a state that has traditionally leaned “red”—decided to opt into the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) Medicaid expansion in 2023, it seemed that political debates over the ACA might be in the rearview mirror. But last November, former president Trump—currently the leading candidate for the Republican presidential nomination after strong wins in the Iowa caucuses and New Hampshire primary—indicated his intent to replace the ACA with something else. President Biden is now making protection and expansion of the ACA a key part of his 2024 campaign. What had appeared to be a settled issue may be a significant point of contention in the 2024 presidential election and beyond.

Although we do not anticipate any significant healthcare-related legislation in advance of the 2024 elections, healthcare leaders should be prepared for renewed attention to the costs of government-funded healthcare programs leading up to and following the elections. The national debt has increased rapidly over the past 20 years, tripling from $11 trillion in 2003 to $33 trillion in 2023. If the deficit and national debt become an important issue in the election, a move toward a balanced budget—akin to the Balanced Budget Act of 1997—post election could lead to further cuts to Medicare and Medicaid.

- Temporary relief payments. Health systems continue to receive one-time cash infusions through the 340B settlement, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) payments and other governmental programs. Approximately 1,600 hospitals have or will be receiving a lump-sum payment to compensate them for a change in the Department of Health & Human Services’ (HHS’s) reimbursement rates for the 340B program from 2018 to 2022, which was ruled unlawful by the Supreme Court in a 2022 decision. The total amount to be distributed is approximately $9 billion and began hitting bank accounts in January 2024.

But what the right hand giveth, the left hand taketh away. Budget neutrality requirements will force HHS to recoup this offset—amounting to approximately $7.8 billion—which it will do by reducing payments for non-drug items and services to all Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) providers by 0.5% until the offset has been fully recouped, beginning in calendar year 2026. HHS estimates that this process will take approximately 16 years. Is this a harbinger of lower payments on other key governmental programs?

Many hospitals also continue to receive Covid-related payments from FEMA for expenses occurred during the pandemic. In addition, state supplemental payments—especially under Medicaid managed care and fee-for-service programs—are providing some relief. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has issued a proposed rule, however, that would limit states’ use of provider-based funding sources, such as provider taxes, and cap the rate of growth for state-directed payments.

As all of these payment programs dry up over the next few years, hospitals will need to replace the revenue and/or get leaner on the expense side in order to maintain today’s level of performance.

- The hollowing of the commercial health insurance market. Our colleague, Joyjit Saha Choudhury, recently published a blog on the hollowing of the commercial health insurance market, driven by long-term concerns over the affordability of healthcare. While volumes have been recovering to pre-pandemic levels, this hollowing threatens the loss of the most profitable volumes and will pressure hospitals and health systems to create and deliver value, compete for inclusion in narrow networks, and develop more direct relationships with the employer community.

Related, the growing penetration of Medicare Advantage plans is reducing the number of traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Many CFOs report that these programs can be the most difficult with which to work given their high denial rates and required pre-authorization rates. A new rule requiring insurers to streamline prior authorizations for Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, and Affordable Care Act plans may help alleviate this issue; however, it will be incumbent upon management teams to stay ahead of them. Aging demographics are also reducing the percentage of commercially insured patients for many hospitals and health systems, further exacerbating the problem. This combination of fewer commercial patients (who often subsidize governmental patients) and more pressure on receiving the duly owed commercial revenue threatens to be an ongoing headache for management teams.

- Ongoing impact of the Baby Boom generation. Despite the good news on inflation—and indications that the Fed may begin lowering interest rates in 2024—the economy is by no means out of the woods yet. The Baby Boom generation, which holds more than 50% of the wealth in the U.S. and is seemingly price agnostic, still has many years of spending ahead, in healthcare and general purchasing. This will likely continue to pressure inflation, especially in the healthcare sector, where demand will continue to grow. As the generation starts to shrink, the resulting wealth transfer will be the largest ever in our country’s history and have profound (and unforeseen) consequences on the overall economy and healthcare in general.

In sum, these other factors will continue to affect the sector (both positively and negatively) and require health system management teams to navigate an everchanging world. While many signs point toward short-term relief, the longer-term challenges persist. Improvements in the short term may, however, provide the opportunity to reposition organizations for the future.

How hospitals and health systems should respond

Healthcare leaders should view ongoing uncertainty in the political and economic climate as a tailwind as much as a headwind. This uncertainty, in other words, should be a motivation to put in place strategies that will buffer healthcare organizations from potential bumps in the road ahead. Setting balance sheet strategy should be a part of an organization’s planning process.

How an organization sets that strategy, measures its performance, and makes improvements will set apart top-performing organizations.

Although heightened debt issuance early in 2024 signals a return for many systems to a climate of investment, there is still limited energy around strategy and debt conversations in many boardrooms, especially in those organizations where financial improvement continues to lag. The last two years have illustrated that hospitals and health systems will not be able to cut their way to profitability. Lackluster performance cannot and will not improve without some level of strategic change, whether it is through market share gains, payer mix shift, or operational improvements. This strategic change requires investment and investment requires capital. Capital can be obtained in many forms—whether through growth in capital reserves, improved cash flow, or new debt issuance—but is essential for change. Reengaging in conversations about strategy and growth should be an imperative in 2024 and will require reexamining how that growth is funded.

Healthcare leaders should engage their partners as they continue or refocus on:

- Changing the conversation from debt capacity to capital capacity. Management teams need to determine what they can afford to spend on capital if the new normal of cash flow will be constrained going forward. Capital capacity is and should be agnostic to the source of that capital, such as debt, cash flow from operations, or liquidity reserves. Healthcare leaders must focus on what they can spend, before deciding how to fund that spending. The conversation will need to balance investment for the future with maintaining key credit metrics in the short term.

- Conducting a capitalization analysis. Separate but related to the previous entry, how much leverage should your organization have relative to its overall capitalization? Ostensibly, many organizations have been paying principal while curtailing borrowing needs, so capitalization may have improved. While that may be the case, many organizations have depleted reserves and/or experienced investment losses that have reduced capitalization. Understanding where the organization stands is an essential next step.

- Evaluating surplus return. Consider surplus return as investment income net of interest expense. Organizations should evaluate their ability to reliably generate both operating cash flow and net surplus. How an organization’s balance sheet is positioned to generate returns and manage risk will be a critical success factor.

- Focusing on the metrics that matter. These include operating cashflow margin, cash to debt, debt to revenue, and days cash on hand. As key metrics for rating analysts and investors continue to evolve, management teams need to make sure they are focused on the correct numbers. The discussion should be dually focused on ensuring adequate-to-ample headroom to basic financial covenants as well as a comparison to key medians and peers. Strong financial planning will address how these metrics can be improved over time through synergies, growth, and diversification strategies.

Although it has been a difficult few years, hospitals and health systems seem to have moved onto a more stable footing over the last twelve months. In order to build upon the upward trajectory, now is the time to harness strategy, planning, and investment to move organizations from stability to sustainability.