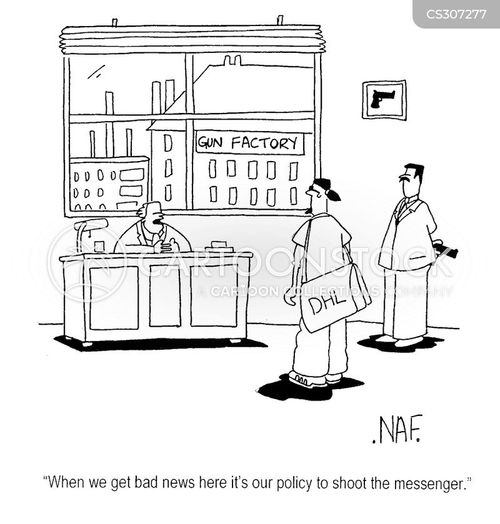

Cartoon – Importance of Transparency

https://mailchi.mp/9f24c0f1da9a/the-weekly-gist-june-5-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

A new analysis from the CDC this week confirmed what we have been hearing anecdotally from health systems for several weeks—as the coronavirus lockdown took hold, there was a precipitous drop in visits to hospital emergency departments. According to the study, visits were down by 42 percent in the month of April compared to the previous year, and despite a rebound in May, were still 26 percent lower than a year ago. Visits in the Northeast dropped the most, as did those among women, and children under 14.

Although visits for minor ailments and symptoms declined the most, even more disconcerting was the drop in visits for chest pain, echoing the concern we’ve heard in many parts of the country that many patients may have suffered minor heart attacks without being treated, or may have waited to be seen until significant damage had been done.

As non-emergent visits have begun to return to many facilities, we continue to hear that emergency department and urgent care volume remains relatively low.

Survey data indicate that patients are fearful of becoming infected with coronavirus if they visit healthcare facilities—especially, it seems, ones where they’ll be forced to wait.

While many providers are investing in messaging campaigns to assure patients it’s safe to return, this nightmarish first-person account by one healthcare insider provides a useful cautionary tale.

Visiting a surgeon for a pre-op consult, she found the experience of visiting a COVID-era hospital downright dystopian. Simply touting safety precautions by itself won’t make patients more comfortable—they’ll need to see and feel that measures are in place to make time spent in a care setting as efficient and reassuring as possible. Otherwise, like the insider in question, they’ll take their business elsewhere. There’s work to be done.

Coronavirus has swept through a Tyson pork processing plant in Storm Lake, Iowa, with 555 employees of 2,517 testing positive, fueling renewed concerns over safety measures at meatpacking plants.

On Wednesday, with suspicions the plant was the site of a new outbreak, Iowa’s Department of Public Health Deputy Director Sarah Reisetter said the state would only confirm outbreaks at businesses where 10% of employees test positive and only if the news media inquires about them specifically.

According to the Des Moines Register, cases in Buena Vista County more than doubled on Tuesday, and Reisetter is now confirming around 22% of the employees at the Storm Lake facility tested positive.

“We’ve determined confirming outbreaks at businesses is only necessary when the employment setting constitutes a high-risk environment for the potential of Covid-19 transmission,” Reisetter added.

On April 28, President Trump signed an executive order using the authority of the Defense Production Act to compel meat processing plants to remain open, but it hasn’t stopped facilities from shuttering to address low staffing and safety issues.

Tyson was previously forced to shut down its largest pork processing facility, located in Waterloo, Iowa, on April 22 following a number of coronavirus cases stemming from the plant, as well as worker absenteeism.

Other meatpacking facilities across the state have also been forced to address outbreaks, including plants owned by Smithfield Foods and JBS.

State lawmakers and mayors in Iowa have complained about not getting information about the ongoing situations at meatpacking facilities until it’s too late. Sioux City Mayor Bob Scott said because Tyson isn’t based in the state, they don’t need to report numbers to them. Iowa Rep. Ras Smith criticized Governor Kim Reynolds and the Department of Health’s stance on the delays in reporting numbers.

Food processing facilities have been the site of numerous outbreaks around the country, with Trump pushing for them to remain open amid fears of food shortages. Earlier in May, the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, the largest meatpacking workers union, derided Trump’s executive order, saying that since its signing, “The administration has failed to take the urgent action needed to enact clear and enforceable safety standards at these meatpacking plants.” There are 18,524 confirmed cases of the coronavirus in Iowa.

Nations fighting in World War I were reluctant to report their flu outbreaks.

“Spanish flu” has been used to describe the flu pandemic of 1918 and 1919 and the name suggests the outbreak started in Spain. But the term is actually a misnomer and points to a key fact: nations involved in World War I didn’t accurately report their flu outbreaks.

Spain remained neutral throughout World War I and its press freely reported its flu cases, including when the Spanish king Alfonso XIII contracted it in the spring of 1918. This led to the misperception that the flu had originated or was at its worst in Spain.

“Basically, it gets called the ‘Spanish flu’ because the Spanish media did their job,” says Lora Vogt, curator of education at the National WWI Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri. In Great Britain and the United States—which has a long history of blaming other countries for disease—the outbreak was also known as the “Spanish grip” or “Spanish Lady.”

Historians aren’t actually sure where the 1918 flu strain began, but the first recorded cases were at a U.S. Army camp in Kansas in March 1918. By the end of 1919, it had infected up to a third of the world’s population and killed some 50 million people. It was the worst flu pandemic in recorded history, and it was likely exacerbated by a combination of censorship, skepticism and denial among warring nations.

“The viruses don’t care where they come from, they just love taking advantage of wartime censorship,” says Carol R. Byerly, author of Fever of War: The Influenza Epidemic in the U.S. Army during World War I. “Censorship is very dangerous during a pandemic.”

Patients lie in an influenza ward at the U.S. Army Camp Hospital No. 45 in Aix-les-Baines, France, during World War I.

Corbis/Getty Images

When the flu broke out in 1918, wartime press censorship was more entrenched in European countries because Europe had been fighting since 1914, while the United States had only entered the war in 1917. It’s hard to know the scope of this censorship, since the most effective way to cover something up is to not leave publicly-accessible records of its suppression. Discovering the impact of censorship is also complicated by the fact that when governments pass censorship laws, people often censor themselves out of fear of breaking the law.

In Great Britain, which fought for the Allied Powers, “the Defense of the Realm Act was used to a certain extent to suppress…news stories that might be a threat to national morale,” says Catharine Arnold, author of Pandemic 1918: Eyewitness Accounts from the Greatest Medical Holocaust in Modern History. “The government can slam what’s called a D-Notice on [a news story]—‘D’ for Defense—and it means it can’t be published because it’s not in the national interest.”

Both newspapers and public officials claimed during the flu’s first wave in the spring and early summer of 1918 that it wasn’t a serious threat. The Illustrated London News wrote that the 1918 flu was “so mild as to show that the original virus is becoming attenuated by frequent transmission.” Sir Arthur Newsholme, chief medical officer of the British Local Government Board, suggested it was unpatriotic to be concerned with the flu rather than the war, Arnold says.

The flu’s second wave, which began in late summer and worsened that fall, was far deadlier. Even so, warring nations continued to try to hide it. In August, the interior minister of Italy—another Allied Power—denied reports of the flu’s spread. In September, British officials and newspaper barons suppressed news that the prime minister had caught the flu while on a morale-boosting trip to Manchester. Instead, the Manchester Guardian explained his extended stay in the city by claiming he’d caught a “severe chill” in a rainstorm.

Warring nations covered up the flu to protect morale among their own citizens and soldiers, but also because they didn’t want enemy nations to know they were suffering an outbreak. The flu devastated General Erich Ludendorff’s German troops so badly that he had to put off his last offensive. The general, whose empire fought for the Central Powers, was anxious to hide his troops’ flu outbreaks from the opposing Allied Powers.

“Ludendorff is famous for observing [flu outbreaks among soldiers] and saying, oh my god this is the end of the war,” Byerly says. “His soldiers are getting influenza and he doesn’t want anybody to know, because then the French could attack him.”

Patients at U. S. Army Hospital No. 30 at a movie wear masks because of an influenza epidemic.

The National Library of Medicine

The United States entered WWI as an Allied Power in April 1917. A little over a year later, it passed the 1918 Sedition Act, which made it a crime to say anything the government perceived as harming the country or the war effort. Again, it’s difficult to know the extent to which the government may have used this to silence reports of the flu, or the extent to which newspapers self-censored for fear of retribution. Whatever the motivation, some U.S. newspapers downplayed the risk of the flu or the extent of its spread.

In anticipation of Philadelphia’s “Liberty Loan March” in September, doctors tried to use the press to warn citizens that it was unsafe. Yet city newspaper editors refused to run articles or print doctors’ letters about their concerns. In addition to trying to warn the public through the press, doctors had also unsuccessfully tried to convince Philadelphia’s public health director to cancel the march.

The war bonds fundraiser drew several thousand people, creating the perfect place for the virus to spread. Over the next four weeks, the flu killed 12,191 people in Philadelphia.

Similarly, many U.S. military and government officials downplayed the flu or declined to implement health measures that would help slow its spread. Byerly says the Army’s medical department recognized the threat the flu posed to the troops and urged officials to stop troop transports, halt the draft and quarantine soldiers; but they faced resistance from the line command, the War Department and President Woodrow Wilson.

Wilson’s administration eventually responded to their pleas by suspending one draft and reducing the occupancy on troop ships by 15 percent, but other than that it didn’t take the extensive measures medical workers recommended. General Peyton March successfully convinced Wilson that the U.S. should not stop the transports, and as a result, soldiers continued to get sick. By the end of the year, about 45,000 U.S. Army soldiers had died from the flu.

The pandemic was so devastating among WWI nations that some historians have suggested the flu hastened the end of the war. The nations declared armistice on November 11 amid the pandemic’s worst wave.

In April 1919, the flu even disrupted the Paris Peace Conference when President Wilson came down with a debilitating case. As when the British prime minister had contracted the flu back in September, Wilson’s administration hid the news from the public. His personal doctor instead told the press the president had caught a cold from the Paris rain.

https://mailchi.mp/f4f55b3dcfb3/the-weekly-gist-may-15-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

Last week, we reported that consumer healthcare confidence is down—it’s unclear when people will feel safe enough to return to reopened care sites. Recent polling data provided by our friends at Public Opinion Strategies, and detailed in the graphic below, shows that direct provider communication is crucial to reengaging patients and rebuilding their trust in seeking care.

The majority of Americans receive health-related information from news media outlets, but only 18 percent say they regularly hear it from their doctors or providers—yet 66 percent of Americans view doctors and providers as highly trusted sources of information. Consumers are looking to providers to demonstrate and communicate a commitment to safe operations that are as “COVID-free” as possible.

In particular, many patients would feel safe returning to a healthcare facility if their doctor assured them it’s safe to go. Health systems are taking myriad steps to provide COVID-safe care—staggering appointments, eliminating waiting rooms, screening temperatures upon arrival, providing masks, enhancing sterilization and testing at-risk patients—more communication about the specifics of their efforts, directly to patients, will be vital to restoring consumer confidence. (See more survey data gathered by Public Opinion Strategies here.)

Like a lot of major health systems, CommonSpirit Health is making strides to reopen elective procedures canceled due to COVID-19.

Some facilities have already resumed some surgical procedures, and others are going to start scheduling such procedures as soon as Monday.

To get started, officials say, the health system giant recently created a toolkit that they sent to its 137 hospitals that stretch across more than 20 states outlining testing, screening and supply protocols. CommonSpirit’s toolkit builds on a framework put out in recent weeks by the American Hospital Association, the American College of Surgeons and other provider groups.

A key message: Hospitals must also make sure to keep one eye on the virus and its ongoing spread in the community on a daily basis and be ready to respond accordingly. CommonSpirit says that facilities need to coordinate with local and state authorities.

“The virus isn’t going away because we reopened,” Barbara Pelletreau, senior vice president for patient safety at CommonSpirit, told FierceHealthcare.

Here’s a look at what else the health system’s new toolkit advises:

1. Assess: The toolkit offers five phases of surgical care, Pelletreau said. In the first phase, a facility must look at how to reassess the health status of patients since the cancellation of their procedure, she said.

Hospitals must adhere to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ requirement that there is a physical examination and history of a patient within 30 days of any procedure. “This will verify if there has been no significant interim change in patient’s health status,” the toolkit said.

Hospitals can rely on telehealth for part of this evaluation.

Testing is also a critical part of the restart. Facilities should test patients before surgical procedures and tell patients to remain at home before the results come in to limit any new potential exposure.

A hospital must also create a process to determine next steps if patient testing is not available or results haven’t come back in time for the surgery.

2. Designate leadership and coordinate: As they prepare to get going again, facilities should establish a prioritization policy committee that has members from surgery, anesthesia and nursing.

The committee should examine which types of procedures should get priority to resume.

3. Ensure they have enough PPE: They also need to make sure they have enough personal protective equipment (PPE) to handle not just any new procedures but also another wave of COVID-19 cases.

For instance, one part of the toolkit recommends a facility to have a minimum of four days of PPE on hand and projection of new inventory arriving for the next two weeks.

As facilities ramp up, they must ensure they have enough primary and adjunct personnel. A hospital must also put out guidelines for who is present during intubation and extubation of the patient and how to use PPE.

However, a key element is harder to address: confidence among patients.

“In the end, you can have all the clinical facts. But it is, ‘How do you feel about your safety?’” Pelletreau said. “How do you feel about going to the grocery store or a hospital that delivers amazing medical care?”

Pelletreau said that CommonSpirit is now also working on messaging to its own employees and to the community to assure patients it is safe to return to the hospital for needed medical care. That includes several communication resources to show examples of the work it is doing, from ramped-up testing to more stringent cleaning protocols, to ensure surgical procedures can be performed safely.

“Consider a proactive approach to communicating with staff, patients, physicians and the community,” the toolkit said. “Recognize the significant interest and questions from our key audiences.”

https://mailchi.mp/aa7806a422dd/the-weekly-gist-may-8-2020?e=d1e747d2d8

As non-essential businesses begin to reopen, there’s no guarantee that merely opening the doors will make customers return. A recent Morning Consult poll provides an assessment of the impact of COVID-19 on consumer confidence: fewer than one in five US adults are currently comfortable doing (formerly) everyday activities like eating at a restaurant or going to a shopping mall.

The graphic below provides similar data for healthcare. Consumers’ willingness to visit healthcare providers in person for non-COVID care is only slightly better, at 21 percent. Which providers might see patients return most quickly?

Consumers say they are about twice as likely to visit their primary care doctor’s office than other healthcare facilities, including hospitals, specialists, and walk-in clinics. And when it comes to scheduling a routine in-office visit, nearly half say they will wait two to six months, with almost one in ten not comfortable going to a doctor’s office in person for a year or more.

Healthcare facilities face an uphill battle in bringing back patients—many of whom have ongoing chronic diseases that necessitate care now. Reaching patients through telemedicine and providing concrete messages about how they can safely see their doctor will be critical to staving off a tide of disease exacerbations that will mount as fear delays much-needed care.