The executives featured in this article are all speaking at the Becker’s Healthcare 13th Annual Meeting April 3-6, 2023, at the Hyatt Regency in Chicago.

Question: What will hospitals and health systems look like in 10 years? What will be different and what will be the same?

Michael A. Slubowski. President and CEO of Trinity Health (Livonia, Mich.): In 10 years, inpatient hospitals will be more focused on emergency care, intensive/complex care following surgery or complex medical conditions, and short-stay/observation units. Only the most complex surgical cases and complex medical cases will be inpatient status. Most elective surgery and diagnostic services will be done in freestanding surgery, procedural and imaging centers. Many patients with chronic medical conditions will be managed at home using digital monitoring. More seniors will be cared for in homes and/or in PACE programs versus skilled nursing facilities.

Mark A. Schuster, MD, PhD. Founding Dean and Chief Executive Officer of Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine (Pasadena, Calif.): The future of hospitals might not actually unfold in hospitals. I expect that more and more of what we now do in hospitals will move into the home. The technology that makes this transition possible is already out there: Remote monitoring of vital signs and lab tests, remote visual exams, and videoconferencing with patients. And all of this technology will improve even more over the next 10 years — turning at-home care from a dream into a reality.

Imagine no longer being kept awake all night by beeps and alarms coming from other patients’ rooms or kept away from family by limited visiting hours. The benefits are especially welcome for people who live in rural places and other areas with limited medical facilities. Who knows? Maybe robotics will make some in-home surgeries not so far off!

Of course, not all patients have a safe or stable home environment where they could receive care, so hospitals aren’t going away anytime soon. I’m not suggesting that most current patients could be cared for remotely in a decade — but I do think we’re moving in that direction. So those of us who work in education will need to train medical, nursing, and other students for a healthcare future that looks quite different from the healthcare present and takes place in settings we couldn’t imagine 10 years ago.

Shireen Ahmad. System Director, Operations and Finance of CommonSpirit Health (Chicago): The biggest change I anticipate is a continuation in the decentralization of health services delivery that has typically been provided by hospitals. This will result in a reduction of hospitals with fewer services performed in acute settings and with more services provided in non-acute ones.

With recent reimbursement changes, CMS is helping to set the tone of where care is delivered. Hospitals are beginning to rationalize services, including who and where care is delivered. For example, pharmacies often carry clinics that provide vaccinations, but in France, one can go to a pharmacy for care and sterilization of minor wounds while only paying for bandages, medication and other supplies used in the visit. I would not be surprised if, in 10 years, one could get an MRI at their local Walmart or schedule routine screenings and tests at the grocery store with faster, more accurate results as they check out their produce.

If the pandemic has taught us anything, there will always be a need for acute care and our society will always need hospitals to provide care to sick patients. This is not something I would anticipate changing. However, the need to provide most care in a hospital will change with the result leading to fewer hospitals in total. Far from being a bleak outlook, however, I believe that healthier, sustainable health systems will prevail if they are able to provide a greater spectrum of care in broader settings focussing on quality and convenience.

Gerard Brogan. Senior Vice President and Chief Revenue Officer of Northwell Health (New Hyde Park, N.Y.): Operationally, hospitals and health systems will be more designed around the patient experience rather than the patient accommodating to the hospital design and operations. Specifically, more geared toward patient choice, shopping for services, and price competition for out-of-pocket expenses. In order to bring costs down, rational control of utilization will be more important than ever. Hopefully, we will be able to shrink the administrative costs of delivering care. Structurally, more care will continue to be done ambulatory, with hospitals having a greater proportion of beds having critical care capability and single rooms for infection control, putting pressure on the cost per square foot to operate. Sustainable funding strategies for safety net hospitals will be needed.

Mike Gentry. Executive Vice President and COO of Sentara Healthcare (Norfolk, Va.): During the next 10 years, more rural hospitals will become critical assessment facilities. The legislation will be passed to facilitate this transition. Relationships with larger sponsoring health systems will support easy transitions to higher acuity services as required. In urban areas, fewer hospitals with greater acuity and market share will often match the 50 percent plus market share of health plans. The ambulatory transition will have moved beyond only surgical procedures into outpatient but expanded historical medical inpatient status in ED/observation hubs.

The consumer/patient experience will be vastly improved. Investments in mobile digital applications will provide greatly enhanced communication, transparency of clinical status, timelines, the likelihood of expected outcomes and cost. Patients will proactively select from a menu of treatment options provided by predictive AI. The largest 10 health systems will represent 25 percent of the total U.S. acute care market share, largely due to consumer-centric strategic investments that have outpaced their competitors. Health systems will have vastly larger pharma operations/footprints.

Ketul J. Patel. CEO of Virginia Mason Franciscan Health (Seattle) and Division President, Pacific Northwest of CommonSpirit Health (Chicago): This is a transformative time in the healthcare industry, as hospitals and healthcare systems are evolving and innovating to meet the growing and changing needs of the communities we serve. The pandemic accelerated the digital transformation of healthcare. We have seen the proliferation of new technologies — telemedicine, artificial intelligence, robotics, and precision medicine — becoming an integral part of everyday clinical care. Healthcare consumers have become empowered through technology, with greater control and access to care than ever before.

Against this backdrop, in the next decade we’ll see healthcare consumerism influencing how health systems transform their hospitals. We will continue incorporating new technologies to improve healthcare delivery, offering more convenient ways to access high-quality care, and lowering the overall cost of care.

SMART hospitals, including at Virginia Mason Franciscan Health, are utilizing AI to harness real-time data and analysis to revolutionize patient and provider experiences and improve the quality of care. VMFH was the first health system in the Pacific Northwest to introduce a virtual hospital nearly a decade ago, which provides virtual services in the hospital across the continuum of care to improve quality and safety through remote patient monitoring and care delivery.

As hospitals become more high-tech, more nimble, and more efficient over the next 10 years, there will be less emphasis on brick-and-mortar buildings as we continue to move care away from the hospital toward more convenient settings for the patient. We recently launched VMFH Home Recovery Care, which brings all the essential elements of hospital-level care into the comfort and convenience of patients’ homes, offering a safe and effective alternative to the traditional inpatient stay.

Health systems and hospitals must simplify the care experience while reducing the overall cost of care. VMFH is building Washington state’s first hybrid emergency room/urgent care center, which eliminates the guesswork for patients unsure of where to go for care. By offering emergent and urgent care in a single location, patients get the appropriate level of care, at the right price, in one convenient location.

As healthcare delivery becomes more sophisticated in this digital age, we must not lose sight of why we do this work: our patients. There is no device or innovation that can truly replace the care and human intelligence provided by our nurses, APPs and physicians. So, while hospitals and health systems might look and feel different in 2033, our mission will remain the same: to provide exceptional, compassionate care to all — especially the most vulnerable.

David Sylvan. President of University Hospitals Ventures (Cleveland): American healthcare is facing an imperative. It’s clear that incremental improvements alone won’t manifest the structural outcomes that are largely overdue. The good news is that the healthcare industry itself has already initiated the disruption and self-disintermediation. I would hope that in the next 10 years, our offerings in healthcare truly reflect our efforts to adopt consumerism and patient choice, alleviate equity barriers and harness efficiencies while reducing time waste.

We know that some of this will come about through technology design, build and adoption, especially in the areas of generative artificial intelligence. But we also know that some of this will require a process overhaul, with learnings gleaned from other industries that have already solved adjacent challenges. What won’t change in 10 years will be the empathy and quality of care that the nation’s clinicians provide to patients and their caregivers daily.

Joseph Webb. CEO of Nashville (Tenn.) General Hospital: The United States healthcare industry operates within a culture that embraces capitalism as an economic system. The practice of capitalism facilitates a framework that is supported by the theory of consumerism. This theory posits that the more goods and services are purchased and consumed, the stronger an economy will be. With that in mind, healthcare is clearly a driver in the U.S. economy, and therefore, major capital and technology are continuously infused into healthcare systems. Healthcare is currently approaching 20 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product and will continue to escalate over the next 10 years.

Also, in 10 years, there will be major shifts in ownership structures, e.g., mergers, acquisitions, and consolidations. Many healthcare organizations/hospitals will be unable to sustain operations due to shrinking profit margins. This will lead to a higher likelihood of increasing closures among rural hospitals due to a lack of adequate reimbursement and rising costs associated with salaries for nurses, respiratory therapists, etc., as well as purchasing pharmaceuticals.

Aging baby boomers with chronic medical conditions will continue to dominate healthcare demand as a cohort group. To mitigate the rising costs of care, healthcare systems and providers will begin to rely even more heavily on artificial intelligence and smart devices. Population health initiatives will become more prevalent as the cost to support fragmented care becomes cost-prohibitive and payers such as CMS will continue to lead the way toward value-based care.

Because of structural and social conditions that tend to drive social determinants of health, which are fundamental causes of health disparities, achieving health equity will continue to be a major challenge in the U.S. Health equity is an elusive goal that can only be achieved when there is a more equitable distribution of SDOH.

Gary Baker. CEO, Hospital Division of HonorHealth (Scottsdale, Ariz.): In 10 years, I would expect hospitals in health systems to become more specialized for higher acuity service lines. Providing similar acute services at multiple locations will become difficult to maintain. Recruiting and retaining specialty clinical talent and adopting new technologies will require some redistribution of services to improve clinical quality and efficiency. Your local hospital may not provide a service and will be a navigator to the specialty facilities. Many services will be provided in ambulatory settings as technology and reimbursement allow/require. Investment in ambulatory services will continue for the next 10 years.

Michael Connelly. CEO Emeritus of Bon Secours Mercy Health (Cincinnati): Our society will be forced to embrace economic limits on healthcare services. The exploding elderly population, in combination with a shrinking workforce to fund Medicare/Medicaid and Social Security, will force our health system to ration care in new ways. These realities will increase the role of primary care as the needed coordinator of health services for patients. Diminishing fragmented healthcare and redundant care will become an increasing focus for health policy.

David Rahija. President of Skokie Hospital, NorthShore University HealthSystem (Evanston, Ill.): Health systems will evolve from being just a collection of hospitals, providers, and services to providing and coordinating care across a longitudinal care continuum. Health systems that are indispensable health partners to patients and communities by providing excellent outcomes through seamless, coordinated, and personalized care across a disease episode and a life span will thrive. Providers that only provide transactional care without a holistic, longitudinal relationship will either close or be consolidated. Care tailored to the personalized needs of patients and communities using team care models, technology, genomics, and analytics will be key to executing a personalized, seamless, and coordinated model of care.

Alexa Kimball, MD. President and CEO of Harvard Medical Faculty Physicians at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (Boston): Ten years from now, hospitals will largely look the same — at least from the outside. Brick-and-mortar buildings aren’t going away anytime soon. What will differ is how care is delivered beyond the traditional four walls. Expect to see a more patient-centered and responsive system organized around what individuals need — when and where they need it.

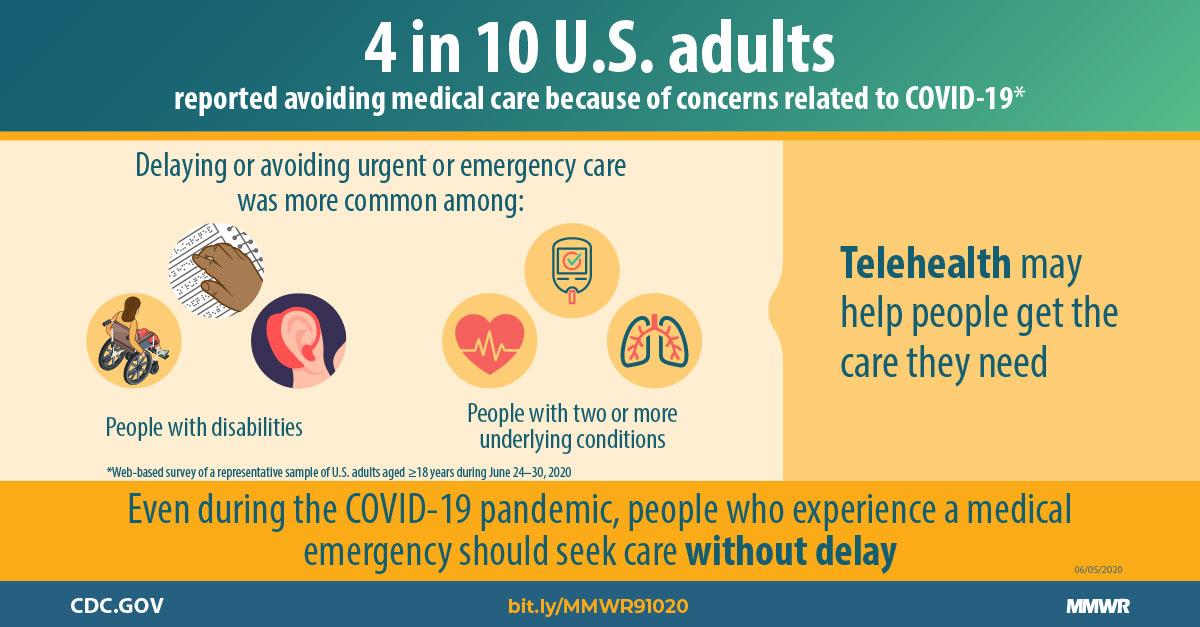

Telehealth and remote patient monitoring will enable greater accessibility for patients in underserved areas and those who cannot get to a doctor’s office. Technology will not only enable doctors to deliver more personalized treatment plans but will also dramatically reshape physician workflows and processes. These digital tools will streamline administrative tasks, integrate voice commands, and provide more conducive work environments. I also envision greater access to data for both providers and patients. New self-service solutions for care management, scheduling, pricing, shopping for services, etc., will deliver a more proactive patient experience and make it easier to navigate their healthcare journey.

Ronda Lehman, PharmD. President of Mercy Health – Lima (Ohio):

This is a highly challenging question to address as we continue to reevaluate how healthcare is being delivered following several difficult years and knowing that financial challenges still loom. That said, when I am asked what it will look like, I am keenly aware of the fact that it only will look that way if we can envision a better way to improve the health of our communities. So 10 years from now, we need to have easier and more patient-driven access to care.

We will need to stop doing ‘to people’ and start caring ‘with people.’ Artificial intelligence and proliferous information that is readily available to consumers will continue to pave the way to patients being more empowered and educated about their options. So what will differentiate healthcare of the future? Enabling patients to make informed decisions.

Undoubtedly, technology will continue to advance, and along with it, the associated costs of research and development, but healthcare can only truly change if providers fundamentally shift their approach to how we care for patients. It is imperative that we need to transform from being the gatekeepers of valuable resources and services to being partners with patients on their journey. If that is what needs to be different, then what needs to be the same? We need the same highly motivated, highly skilled and perhaps most importantly, highly compassionate caregivers selflessly caring for one another and their communities.

Mike Young. President and CEO of Temple University Health System (Philadelphia): Cell therapy, gene therapy, and immunotherapy will continue to rapidly improve and evolve, replacing many traditional procedures with precise therapies to restore normal human function — either through cell transfer, altering of genetic information, or harnessing the body’s natural immune system to attack a particular disease like cancer, cystic fibrosis, heart disease, or diabetes. As a result, hospitals will decrease in footprint, while the labs dedicated to defining precision medicine will multiply in size to support individual- and disease-specific infusion, drug, and manipulative therapies.

Hospitals will continue to shepherd the patient journey through these therapies and also will continue to handle the most complex cases requiring high-tech medical and surgical procedures. Medical education will likely evolve in parallel, focusing more on genetic causation and treatment of disease, as well as proficiency with increasingly sophisticated AI diagnostic technologies to provide adaptive care on a patient-by-patient basis.

Tom Siemers. Chief Executive Officer of Wilbarger General Hospital (Vernon, Texas): My predictions include the national healthcare landscape will be dominated by a dozen or so large systems. ‘Consolidation’ will be the word that describes the healthcare industry over the next 10 years. Regional systems will merge into large, national systems. Independent and rural hospitals will become increasingly rare. They simply won’t be able to make the capital investments necessary to replace outdated facilities and equipment while vying with other organizations for scarce, licensed personnel.

Jim Heilsberg. CFO of Tri-State Memorial Hospital & Medical Campus (Clarkston, Wash.): Tri-State Hospital continues to expand services for outpatient services while maintaining traditionally needed inpatient services. In 10 years, there will be expanded outpatient services that include leveraged technology that will allow the patient to be cared for in a yet-to-be-seen care model, including traditional hospital settings and increasing home care setting solutions.

Jennifer Olson. COO of Children’s Minnesota (St. Paul, Minn.): I believe we will see more and better access to healthcare over the next 10 years. Advances in diagnostics, monitoring, and artificial intelligence will allow patients to access services at more convenient times and locations, including much more frequently at home, thereby extending health systems’ reach well beyond their walls.

What I don’t think will ever change is the heart our healthcare professionals bring with them to work every day. I see it here at Children’s Minnesota and across our industry: the unwavering commitment our caregivers have to help people live healthier lives.

If I had one wish for the future, it would be that we become better equipped to address the social determinants of health: all of the factors outside the walls of our hospitals and clinics that affect our patients’ well-being. Part of that means relaxing regulations to allow better communication and sharing of information among healthcare providers and public and private entities, so we can take a more holistic approach to improve health and decrease disparities. It also will require a fundamental shift in how health and healthcare are paid for.

Stonish Pierce. COO of Holy Cross Health, Trinity Health Florida: Over the next decade, many health systems will pivot from being ‘hospital’ systems to true ‘health’ systems. Based largely on responding to The Joint Commission’s New Requirements to Reduce Health Care Disparities, many health systems will place greater emphasis on reducing health disparities, enhanced attention to providing culturally competent care, addressing social determinants of health (including, but not limited to food, housing and transportation) and health equity. I’m proud to work for Trinity Health, a system that has already directed attention toward addressing health disparities, cultural competency and health equity.

Many systems will pivot from offering the full continuum of services at each hospital and instead focus on the core services for their respective communities, which enables long-term financial sustainability. At the same time, we will witness the proliferation of partnerships as adept health systems realize that they cannot fulfill every community’s needs alone. Depending upon the specialty and region of the country, we may see some transitioning away from the RVU physician compensation model to base salaries and value-based compensation to ensure health systems can serve their communities in the long term.

Driven largely by continued workforce supply shortages, we will also see innovation achieve its full potential. This will include, but not be limited to, virtual care models, robots to address functions currently performed by humans, and increased adoption of artificial intelligence and remote monitoring. Healthcare overall will achieve parity in technological adoption and innovation that we take for granted and have grown accustomed to in industries such as banking and the consumer service industries.

For what will remain the same, we can anticipate that government reimbursement will still not cover the cost of providing care, although systems will transition to offering care models and services that enable the best long-term financial sustainability. We will continue to see payers and retail pharmacies continue to evolve as consumer-friendly providers. We will continue to see systems make investments in ambulatory care and the most critically ill patients will remain in our hospitals.

Jamie Davis. Executive Director, Revenue Cycle Management of Banner Health (Phoenix): I think that we will see a continued shift in places of service to lower-cost delivery sources and unfavorable payer mix movement to Medicare Advantage and health exchange plans, degrading the value of gross revenue. The increased focus on cost containment, value-based care, inflation, and pricing transparency will hopefully push payers and providers to move to a more symbiotic relationship versus the adversarial one today. Additionally, we may see disruption in the technology space as the venture capital and private equity purchase boom that happened from 2019 to 2021 will mature and those entities come up for sale. If we want to continue to provide the best quality health outcomes to our patients and maintain profitability, we cannot look the same in 10 years as we do today.

James Lynn. System Vice President, Facilities and Support Services of Marshfield Clinic Health System (Wis.): There will be some aspects that will be different. For instance, there will be more players in the market and they will begin capturing a higher percentage of primary care patients. Walmart, Walgreens, CVS, Amazon, Google and others will begin to make inroads into primary care by utilizing VR and AI platforms. More and more procedures will be the same day. Fewer hospital stays will be needed for recovery as procedures become less invasive and faster. There will be increasing pressure on the federal government to make healthcare a right for all legal residents and it will be decoupled from employment status. On the other hand, what will stay the same is even though hospital stays will become shorter for some, we will also be experiencing an ever-aging population, so the same number of inpatient beds will likely be needed.