https://unitedstatesofcare.org/resources/2020-health-care-legislative-guide/

ABOUT THE UNITES STATES OF CARE

United States of Care is a nonpartisan nonprofit working to ensure every person in America has access to

quality, affordable health care regardless of health status, social need or income. USofCare works with elected

officials and other state partners across the country by connecting with our extensive health care expert

network and other state leaders; providing technical policy assistance; and providing strategic communications

and political support. Contact USofCare at help@usofcare.org

Health care remains one of the most important problems facing America.

Voters are concerned about access to and the cost for health care and insurance.

Health Care During the COVID Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the need for effective solutions that address both the immediate

challenges and the long-term gaps in our health care systems to ensure people can access quality health care

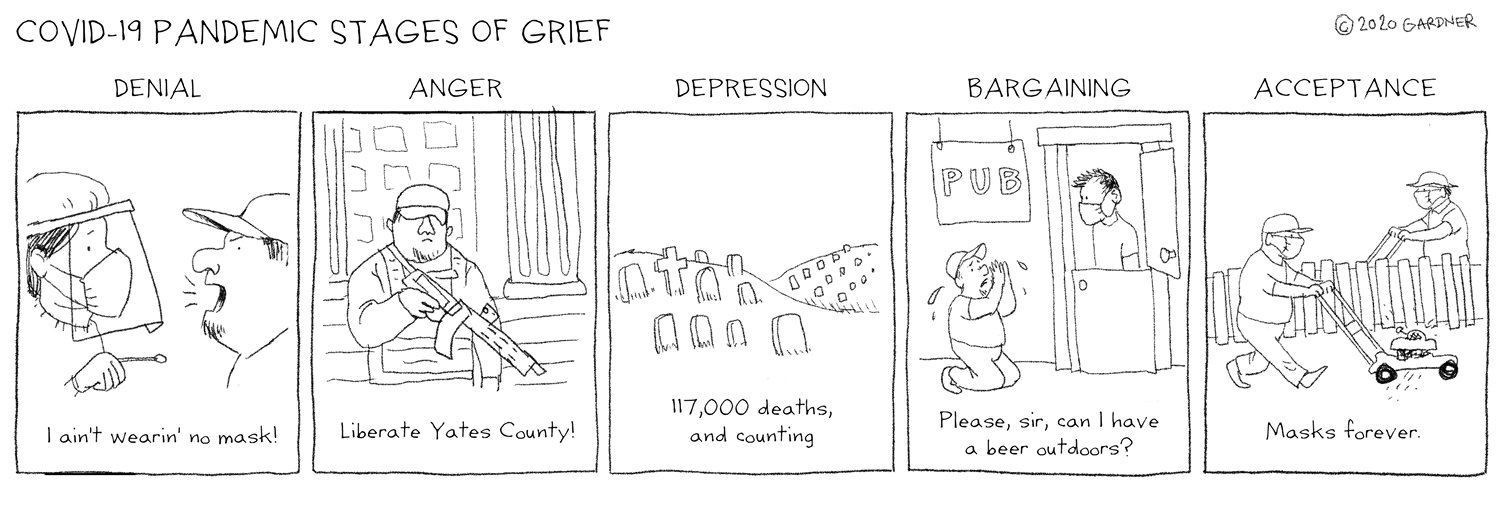

they can afford. Americans are feeling a mix of emotions related to the pandemic, and those emotions are

overwhelmingly negative.*

In addition, the pandemic has illuminated deficiencies of our health care system.

People feel that the U.S. was caught unprepared to handle the pandemic and our losses have

been greater than those of other countries.

People blame government for the inadequate pandemic response, not health care systems.

Health Care During the COVID Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has illuminated the need for effective solutions that address both the immediate challenges and the long-term gaps in our health care systems to ensure people can access quality health care they can afford. In the wake of COVID, policymakers have a critical opportunity to enact solutions to meet their constituents’ short- and long-term health care needs. The 2020 Health Care Legislative Candidate Guide provides candidates with public opinion data, state-specific health care information, key messages and ideas for your health care platform.

Key Messages for Candidates:

- Acknowledge the moment: “Our country is at a pivotal moment. The pandemic, economic recession, and national discussion on race have created a renewed call for action. They have also magnified the critical problems that exist in our health care system.”

- Take an active stance: “It is long past time to examine our systems and address gaps that have existed for decades. We must find solutions and common ground to build a health care system that serves everyone.”

- Commit to prioritizing people’s needs: “I will put people’s health care needs first and I’m already formalizing the ways I gather input and work with community and business leaders to put effective solutions in place.”

- Commit to addressing disparities and finding common ground: “The health care system, as it’s currently structured, isn’t working for far too many. I will work to address the lack of fairness and shared needs to build a health care system that works for all of us.”

Click to access USC_Generic_CandidateEducationGuide.pdf

Promising State Policies to Respond to People’s Health Care Needs

In the wake of COVID, policymakers have a critical opportunity to enact solutions to meet their constituents’

short- and long-term health care needs. Shared needs and expectations are emerging in response to the

pandemic, including the desire for solutions that:

Ensure individuals are able to provide for themselves and their loved ones, especially those worried about

the financial impact of the pandemic.

• Protect against high out-of-pocket costs.

• Expand access to telehealth services for people who prefer it to improve access to care.

• Extend Medicaid coverage for new moms to remove financial barriers to care to support healthier moms

and babies.

Ensure a reliable health care system that is fully resourced to support essential workers and available when

it is needed, both now and after the pandemic.

• Ensure safe workplaces for front-line health care workers and essential workers and increase the capacity to

maintain a quality health care workforce.

• Support hospitals and other health care providers, particularly those in rural or distressed areas.

• Expand mental health services and community workforce to meet increased need.

Ensure a health care system that cares for everyone, including people who are vulnerable and those who

were already struggling before the pandemic hit.

• Adopt an integrated approach to people’s overall health by coordinating people’s physical health, behavioral health

and social service needs.

• Establish coordinated data collection to quickly address needs and gaps in care, especially in vulnerable

communities.

Provide accurate information and clear recommendations on the virus and how to stay healthy and safe.

• Build and maintain capacity for detailed and effective testing and surveillance of the virus.

• Resource and implement contact tracing by utilizing existing programs in state health departments, pursuing

public-private partnerships, or app-based solutions while also ensuring strong privacy protections.

BY THE NUMBERS

The pandemic is showing different impacts for people across the country

that point to larger challenges individuals and families are grappling.

A disproportionate number of those infected by COVID-19 are Black, Indigenous, and people of color. According to recent CDC data, 31.4% of cases and 17% of deaths are among Latino residents and 19.9% of cases and 22.4% of deaths were among Black residents.ix They make up 18.5% and 13.4% of the total population, respectively.

Seniors are at greatest risk. According to a CDC estimate on August 1, 2020, 80% of COVID-19 deaths were among patients ages 65 and older. In 2018, only 16% of Americans were in this age range.

Access to health care in rural areas has only become more challenging during the pandemic and will likely have lasting impacts on rural communities.

The economic fallout of the pandemic has caused nearly 27 million Americans to lose their employer-based health insurance. An estimated 12.7 million would be eligible for Medicaid; 8.4 million could qualify for subsidies on exchanges; leaving 5.7 million who would need to cover the cost of health insurance policies (COBRA policies averaged $7,188 for a single person to $20,576 for a family of four) or remain uninsured.