Category Archives: Financial Instability

The Hospital Makeover—Part 2

America’s hospitals have a $104 billion problem.

That’s the amount you arrive at if you multiply the number of physicians employed by hospitals and health systems (approximately 341,200 as of January 2022, according to data from the Physicians Advocacy Institute and Avalere) by the median $306,362 subsidy—or loss—reported in our Q1 2023 Physician Flash Report.

Subsidizing physician employment has been around for a long time and such subsidies were historically justified as a loss leader for improved clinical services, the potential for increased market share, and the strengthening of traditionally profitable services.

But I am pretty sure the industry did not have $104 billion in losses in mind when the physician employment model first became a key strategic element in the hospital operating model. However, the upward reset in expenses brought on by the pandemic and post-pandemic inflation has made many downstream hospital services that historically operated at a profit now operate at breakeven or even at a loss. The loss leader physician employment model obviously no longer works when it mostly leads to more losses.

This model is clearly broken and in demand of a near-term fix. Perhaps the critical question then is how to begin? How to reconsider physician employment within the hospital operating plan?

Out of the box, rethink the physician productivity model. Our most recent Physician Flash Report data shows that for surgical specialties, there was a median $77 net patient revenue per provider wRVU. For the same specialties, there was a median $80 provider paid compensation per provider wRVU. In other words, before any other expenses are factored in, these specialties are losing $3 per wRVU on paid compensation alone. Getting providers to produce more wRVUs only makes the loss bigger.

It’s the classic business school 101 problem.

If a factory is losing $5 on every widget it produces, the answer is not to produce more widgets. Rather, expenses need to come down, whether that is through a readjustment of compensation, new compensation models that reward efficiency, or the more effective use of advanced practice providers.

Second, a number of hospital CEOs have suggested to me that the current employed physician model is quite past its prime. That model was built for a system of care that included generally higher revenues, more inpatient care, and a greater proportion of surgical vs. medical admissions. But overall, these trends were changing and then were accelerated by the Covid pandemic. Inpatient revenue has been flat to down. More clinical work continues to shift to the outpatient setting and, at least for the time being, medical admissions have been more prominent than before the pandemic.

Taking all this into account suggests that in many places the employed physician organizational and operating model is entirely out of balance. One would offer the calculated guess that there are too many coaches on the team and not enough players on the field. This administrative overhead was seemingly justified in a different loss leader environment but now it is a major contributor to that $104 billion industry-wide loss previously calculated.

Finally, perhaps the very idea of physician employment needs to be rethought.

My colleagues Matthew Bates and John Anderson have commented that the “owner” model is more appealing to physicians who remain independent then the “renter” model. The current employment model offers physicians stability of practice and income but appears to come at the cost of both a loss of enthusiasm and lost entrepreneurship. The massive losses currently experienced strongly suggest that new models are essential to reclaim physician interest and establish physician incentives that result in lower practice expenses, higher practice revenues, and steadily reduced overall subsidies.

Please see this blog as an extension of my last blog, “America’s Hospitals Need a Makeover.” It should be obvious that by analogy we are not talking about a coat of paint here or even new appliances in the kitchen.

The financial performance of America’s hospitals has exposed real structural flaws in the healthcare house. A makeover of this magnitude is going to require a few prerequisites:

- Don’t start designing the renovation unless you know specifically where profitability has changed within your service lines and by explicitly how much. Right now is the time to know how big the problem is, where those problems are located, and what is the total magnitude of the fix.

- The Board must be brought into the discussion of the nature of the physician employment problem and the depth of its proposed solutions. Physicians are not just “any employees.” They are often the engine that runs the hospital and must be afforded a level of communication that is equal to the size of the financial problem. All of this will demand the Board’s knowledge and participation as solutions to the physician employment dilemma are proposed, considered, and eventually acted upon.

The basic rule of home renovation applies here as well: the longer the fix to this problem is delayed the harder and more expensive the project becomes. The losses set out here certainly suggest that physician employment is a significant contributing factor to hospitals’ current financial problems overall. It would be an understatement to say that the time to get after all of this is right now.

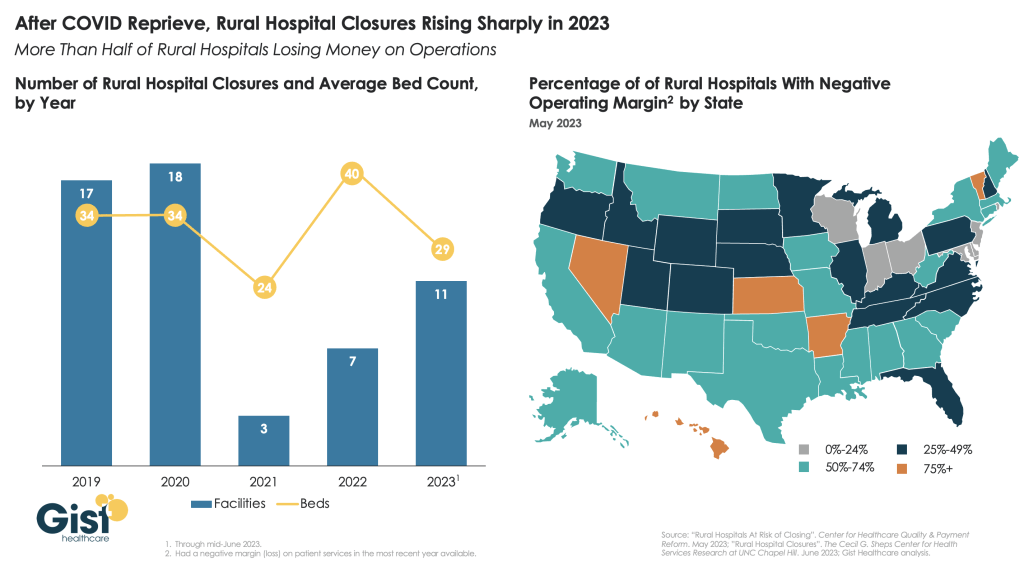

Rural hospital closures rising again with end of COVID aid

https://mailchi.mp/7f59f737680b/the-weekly-gist-june-30-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

After a brief reprieve thanks to COVID relief funds, rural hospital closures are once again on the rise, with 11 facilities already closing in the first half of this year.

More rural facilities have already closed in 2023 than the previous two years combined, and this year is on pace to be the second-highest number of rural hospital beds lost since 2005.

And the majority of rural hospitals that haven’t closed are experiencing negative operating margins, with almost one in three at immediate or high risk of closure due to declining volumes, shifting payer mix, and increased labor and supply costs.

Leaders at rural hospitals now face difficult decisions including drastically cutting services, merging with a larger system, or closing their doors altogether. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Rural Emergency Hospital Program recently, designed to financially support small rural hospitals that convert to providing emergency services only, but so far program uptake has been limited.

While efforts to prop up hospitals will help to sustain access to care in the near term, rural communities ultimately need a new model for care, with reimagined facilities, supported by enhanced virtual connections to specialists and higher-acuity services.

America’s Hospitals Need a Makeover

A couple of months ago, I got a call from a CEO of a regional health system—a long-time client and one of the smartest and most committed executives I know. This health system lost tens of millions of dollars in fiscal year 2022 and the CEO told me that he had come to the conclusion that he could not solve a problem of this magnitude with the usual and traditional solutions. Pushing the pre-Covid managerial buttons was just not getting the job done.

This organization is fiercely independent. It has been very successful in almost every respect for many years. It has had an effective and stable board and management team over the past 30 to 40 years.

But when the CEO looked at the current situation—economic, social, financial, operational, clinical—he saw that everything has changed and he knew that his healthcare organization needed to change as well. The system would not be able to return to profitability just by doing the same things it would have done five years or 10 years ago. Instead of looking at a small number of factors and making incremental improvements, he wanted to look across the total enterprise all at once. And to look at all aspects of the enterprise with an eye toward organizational renovation.

I said, “So, you want a makeover.”

The CEO is right. In an environment unlike anything any of us have experienced, and in an industry of complex interdependencies, the only way to get back to financial equilibrium is to take a comprehensive, holistic view of our organizations and environments, and to be open to an outcome in which we do things very differently.

In other words, a makeover.

Consider just a few areas that the hospital makeover could and should address:

There’s the REVENUE SIDE: Getting paid for what you are doing and the severity of the patient you are treating—which requires a focus on clinical documentation improvement and core revenue cycle delivery—and looking for any material revenue diversification opportunities.

There is the relationship with payers: Involving a mix of growth, disruption, and optimization strategies to increase payments, grow share of wallet, or develop new revenue streams.

There’s the EXPENSE SIDE: Optimizing workforce performance, focusing on care management and patient throughput, rethinking the shared services infrastructure, and realizing opportunities for savings in administrative services, purchased services, and the supply chain. While these have been historic areas of focus, organizations must move from an episodic to a constant, ongoing approach.

There’s the BALANCE SHEET: Establishing a parallel balance sheet strategy that will create the bridge across the operational makeover by reconfiguring invested assets and capital structure, repositioning the real estate portfolio, and optimizing liquidity management and treasury operations.

There is NETWORK REDESIGN: Ensuring that the services offered across the network are delivered efficiently and that each market and asset is optimized; reducing redundancy, increasing quality, and improving financial performance.

There is a whole concept around PORTFOLIO OPTIMIZATION: Developing a deep understanding of how the various components of your business perform, and how to optimize, scale back, or partner to drive further value and operational performance.

Incrementalism is a long-held business approach in healthcare, and for good reason. Any prominent change has the potential to affect the health of communities and those changes must be considered carefully to ensure that any outcome of those changes is a positive one. Any ill-considered action could have unintended consequences for any of a hospital’s many constituencies.

But today, incrementalism is both unrealistic and insufficient.

Just for starters, healthcare executive teams must recognize that back-office expenses are having a significant and negative impact on the ability of hospitals to make a sufficient operating margin. And also, healthcare executive teams must further realize that the old concept of “all things to all people” is literally bringing parts of the hospital industry toward bankruptcy.

As I described in a previous blog post, healthcare comprises some of the most wicked problems in our society—problems that are complex, that have no clear solution, and for which a solution intended to fix one aspect of a problem may well make other aspects worse.

The very nature of wicked problems argues for the kind of comprehensive approach that the CEO of this organization is taking—not tackling one issue at a time in linear fashion but making a sophisticated assessment of multiple solutions and studying their potential interdependencies, interactions, and intertwined effects.

My colleague Eric Jordahl has noted that “reverting to a 2019 world is not going to happen, which means that restructuring is the only option. . . . Where we are is not sustainable and waiting for a reversion is a rapidly decaying option.”

The very nature of the socioeconomic environment makes doing nothing or taking an incremental approach untenable. It is clearly beyond time for the hospital industry makeover.

The End of the Pandemic Health Emergency is Ill-timed and Short-sighted: The Impact will further Destabilize the Health Industry

The national spotlight this week will be on the debt ceiling stand-off in Congress, the end of Title 42 that enables immigrants’ legal access to the U.S., the April CPI report from the Department of Labor and the aftermath of the nation’s 199th mass shooting this year in Allen TX.

The official end of the Pandemic Health Emergency (PHE) Thursday will also be noted but its impact on the health industry will be immediate and under-estimated.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) logged more than 104 million COVID-19 cases in the US as of late April and more than 11% of adults who had COVID-19 currently have symptoms of long COVID. It comes as the CDC say there’s a 20% chance of a Pandemic 2.0 in the next 2-5 years and the current death toll tops 1000/day in the U.S.

The Immediate impact:

The official end of the PHE means much of the cost for treating Covid will shift to private insurers; access to testing, vaccines and treatments with no out-of-pocket costs for the uninsured will continue through 2024. But enrollees in commercial plans, Medicare, Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program can expect more cost-sharing for tests and antivirals.

That means higher revenues for insurers, increased out of pocket costs for consumers and more bad debt for hospitals and physicians.

At the state level, Medicaid disenrollment efforts will intensify to alleviate state financial obligations for Covid-related health costs. In tandem, state allocations for SNAP benefits used by 1 in 4 long-covid victims will shrink as budget-belts tighten lending to hunger cliff.

That means less access to health programs in many states and more disruption in low-income households seeking care.

The Under-estimated Impact:

The end of the PHE enables politicians to shift “good will” toward direct care workers, home and Veteran’s health services and away from hospitals and specialty medicine who face reimbursement cuts and hostile negotiations with insurers. The April 18, 2023 White House Executive Order which enables increased funding for direct care workers called for prioritization across all federal agencies. Notably, in the PHE, hospitals received emergency funding to treat the Covid-19 patients while utilization and funding for non-urgent services was curtailed. Though the Covid-19 population is still significant, funding for hospitals is unlikely in lieu of in-home and social services programs for at risk populations.

A second unknown is this: As the ranks of the uninsured and under-insured swell, and as affordability looms as a primary concern among voters and employers, provider unpaid medical bills and “bad debt” increases are likely to follow.

Hostility over declining reimbursement between health insurers and local hospitals and medical groups will intensify while the biggest drug manufacturers, hospital systems and health insurers launch fresh social media campaigns and advocacy efforts to advance their interests and demonize their foes.

Loss of confidence in the system and a desire for something better may be sparked by the official end of the PHE. And it’s certain to widen antipathy between insurers and hospitals.

My take:

In this month’s Health Affairs, DePaul University health researchers reported results of their analysis of the association between hospital reimbursement rates and insurer consolidation:

“Our results confirm this prior work and suggest that greater insurer market power is associated with lower prices paid for services nationally. A critical question for policy makers and consumers is whether savings obtained from lower prices are passed on in the form of lower premiums. The relationship to premiums is theoretically ambiguous. It is possible that insurers simply retain the savings in the form of higher profits.”

What’s clear is health insurers are winners and providers—especially hospitals and physicians—are likely losers as the PHE ends. What’s also clear is policymakers are in no mood to provide financial rescue to either.

In the weeks ahead as the debt ceiling is debated, the Federal FY 2024 budget finalized and campaign 2024 launches, the societal value of the entire health system and speculation about its preparedness for the next pandemic will be top of mind.

For some—especially not-for-profit hospitals and insurers who benefit from tax exemptions in favor of community health obligations– it requires rethinking of long-term strategies to serve the public good. And it necessitates their Boards to alter capital and operating priorities toward a more sustainnable future.

The pandemic exposed the disconnect between local health and human services programs and inadequacy of local, state and federal preparedness Given what’s ahead, the end of the Pandemic Health Emergency seems ill-timed and short-sighted: the impact will further destabilize the health industry.

Paul

PS: Saturday, the Allen Premium Outlets, (Allen, TX) was the site of America’s 199th mass shooting this year:

this time, 8 innocents died and 7 remain hospitalized, 4 in critical condition. Sadly, it’s becoming a new normal, marked by public officials who offer “thoughts and prayers” followed by calls for mental health and gun controls. Local law enforcement is deified if prompt or demonized if not. But because it’s a “new normal,” the heroics of EMS, ED and hospitals escapes mention. Medical City Healthcare is where 2 of the 8 drew their last breaths while staff labored to save the other 7. At a time when hospitals are battered by bad press, they deserve recognition for work done like this every day.

The extraordinary decline in not-for-profit healthcare debt issuance

https://mailchi.mp/55e7cecb9d73/the-weekly-gist-may-12-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

Last month, Eric Jordahl, Managing Director of Kaufman Hall’s Treasury and Capital Markets practice, blogged about the dangers of nonprofit healthcare providers’ extremely conservative risk management in today’s uncertain economy.

Healthcare public debt issuance in the first quarter of 2023 was down almost 70 percent compared to the first quarter of 2022. While not the only funding channel for not-for-profit healthcare organizations,

the level of public debt issuance is a bellwether for the ambition of the sector’s capital formation strategies.

While health systems have plenty of reasons to be cautious about credit management right now, it’s important not to underrate the dangers of being too risk averse. As Jordahl puts it: “Retrenchment might be the right risk management choice in times of crisis, but once that crisis moderates that same strategy can quickly become a risk driver.”

The Gist: Given current market conditions, there are a host of good reasons why caution reigns among nonprofit health systems, but this current holding pattern for capital spending endangers their future competitiveness and potentially even their survival.

Nonprofit systems aren’t just at risk of losing a competitive edge to vertically integrated payers, whom the pandemic market treated far more kindly in financial terms, but also to for-profit national systems, like HCA and Tenet, who have been flywheeling strong quarterly results into revamped growth and expansion plans.

Health systems should be wary of becoming stuck on defense while the competition is running up the score.

The Balance Sheet Bridge

https://www.kaufmanhall.com/insights/blog/balance-sheet-bridge

Current Funding Environment

The healthcare financings that came in the past couple of weeks generally did well. Maturities seemed to do better than put bonds, and it remains important to pay attention to couponing and how best to navigate a challenging yield curve. But these are episodic indicators rather than trends, given that the scale of issuance remains muted. Other capital markets—like real estate—are becoming more active and offer competitive funding and different credit considerations relative to debt market options. Credit management continues to be the main driver of low external capital formation, but those looking for outside funding should spend time up front considering the full array of channels and structures.

This Part of the Crisis

And now it’s official. After JPMorgan acquired First Republic Bank—with a whole lot of help from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation—CEO Jamie Dimon declared, “this part of the crisis is over.” Not sure regional bank shareholders would agree, but from Mr. Dimon’s perspective the biggest bank got bigger, which made it a good day.

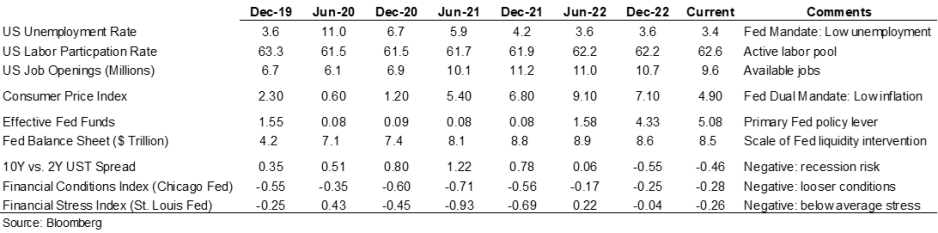

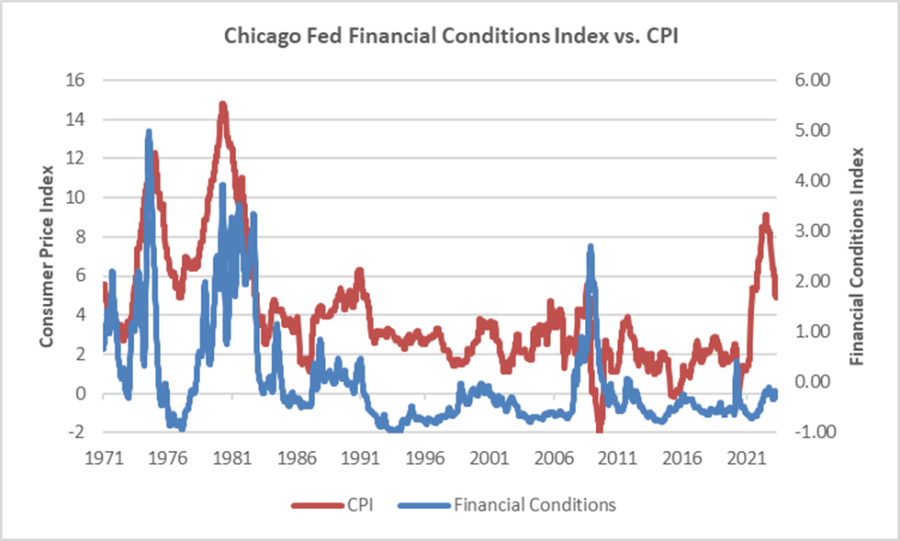

Last week the Federal Reserve raised rates another 25 basis points and the expectation (hope) seems to be that the Fed has reached the peak of its tightening cycle or will at least pause to see if constrictive forces like higher rates and regional bank balance sheet deflation slow activity enough to bring inflation back to the 2.0% Fed target. Assuming this is a pause point, it makes sense to check in on a few economic and market indicators.

Inflation is improving, although it remains well above the Fed’s 2.0% target range, and there are other indicators (like labor participation and unemployment) that have recovered some of the ground lost in 2020. But the weird part remains that this all seems quite civilized. To some, the Treasury curve spread continues to suggest a recession is looming, but in my neighborhood workers are still in short supply, restaurants are busy, and contractors are booked well into the future. Today’s ~3.36% 10-year Treasury rate is less than 100 basis points higher than the average since the start of the Fed interventionist era in 2008 and a whopping 257 basis points lower than the average since 1965. Think about how much capital has been raised in market environments much worse than now (including most of the modern-day healthcare inpatient infrastructure). Again, the main culprit in retarded capital formation is institutional credit management concerns rather than the funding environment.

The major fallout from the Fed’s recent anti-inflation efforts seems concentrated with financial intermediaries rather than consumers (or workers), and the financial intermediary stress the Fed is relying on to help curb economic activity is grounded in their own balance sheet management decisions rather than deteriorating loan portfolios. We’ve looked at this before, but it bears repeating that in the “great inflation” of the 1970s, the Chicago Fed’s Financial Conditions Index reached its highest recorded points (higher means tighter than average conditions) and in this most recent inflationary cycle, that same index has remained consistently accommodative. Can you wring inflation out of a system while retaining relatively accommodative financial conditions? Which begs the question of whether any Fed pause is more about shifting priorities: downgrading the inflation fight in favor of moderating the financial intermediary threat? We might be living a remake of the 1970s version of stubborn inflation, which means that all the attendant issues—rolling volatility across operations, financing, and investing—might be sticking around as well.

Meanwhile, somewhere out in the Atlantic the debt ceiling storm is forming. Who knows whether it will make landfall as a storm or a hurricane, but it does remind us that the operative portion of the Jamie Dimon quote noted above is this part of the crisis is over. The next part of the long saga that is about us climbing out of a deep fiscal and monetary hole will roll in and new variations of the same central challenge will emerge for healthcare leaders.

A Healthcare Makeover

Ken Kaufman has been advancing the idea that healthcare needs a “makeover” to align with post-COVID realities. Look for a piece from him on this soon, but the thesis is that reverting to a 2019 world isn’t going to happen, which means that restructuring is the only option. The most recent National Hospital Flash Report suggests improving margins, but they remain well below historical norms and the labor part of the expense equation is structurally higher. Where we are is not sustainable and waiting for a reversion is a rapidly decaying option.

My contribution to Ken’s argument is to reemphasize that balance sheet is the essential (only) bridge between here and a restructured sector and the journey is going to require very careful planning about how to size, position, and deploy liquidity, leverage, and investments. Of course, the central focus will be on how to reposition operations. But if organic cash generation remains anemic, the gap will be filled by either weakening the balance sheet (drawing down reserves, adding leverage, or adopting more aggressive asset allocation) or by partnering with organizations that have the necessary resources.

Organizations reach the point of greatest enterprise risk when the scale of operating challenges outstrips the scale of balance sheet resources. Missteps are manageable when the imbalance is the product of rapid growth but not when it is the result of deflating resources. If the core imperative is to remake operations, the co-equal imperative is continuously repositioning the balance sheet to carry you from here to whatever defines success.

With bankruptcy looming, Bright Health is fully ditching its insurance business

Embattled insurtech Bright Health will fully ax its insurance business as a potential bankruptcy looms, the company announced Friday.

The company secured an extension to its credit facility through June 30, giving it a few extra months to avoid going belly-up. To ensure it qualifies for the extension, the company must find a buyer for its California-based Medicare Advantage (MA) business by the end of May, according to a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Bright Health revealed March 1 that it had overdrawn its credit and would need to secure $300 million by the end of April to stay afloat.

The MA business includes nearly 125,000 California seniors across its Brand New Day and Central Health Plan brands. In the announcement, Bright said the sale would “substantially bolster” its finances.

“Since our founding, Bright Health has worked to make healthcare simpler, more personal and affordable for consumers,” CEO Mike Mikan said in the announcement. “As our markets evolve, we are taking steps to adapt and ensure our businesses are best positioned for long-term success.”

In late 2022, the company announced that it would exit the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) exchanges and slashed its reach in MA down to just California and Florida as its financial challenges mounted. It later cut the Florida plans as well.

Manny Kadre, lead independent director of Bright Health’s board of directors, said in the announcement that the company has “received inbound interest” about the California MA business as it explores its options.

With the full divestiture of its insurance business, that means Bright Health will be all-in on its NeueHealth care delivery services. Mikan said in the announcement that the segment performed well in the first quarter and has grown to serve about 375,000 value-based care customers.

As Bright shops for a buyer for its MA plans, it’s also continuing to unwind the ACA business, a process that hit a snag as it was hit with a lawsuit from Oklahoma-based health system SSM Health, which alleged that the insurer owed it more than $13 million in unpaid claims.

Bright Health is also under the gun to boost its stock price, as the New York Stock Exchange has threatened to delist its shares. Shares in the company were trading at 17 cents on Friday afternoon.

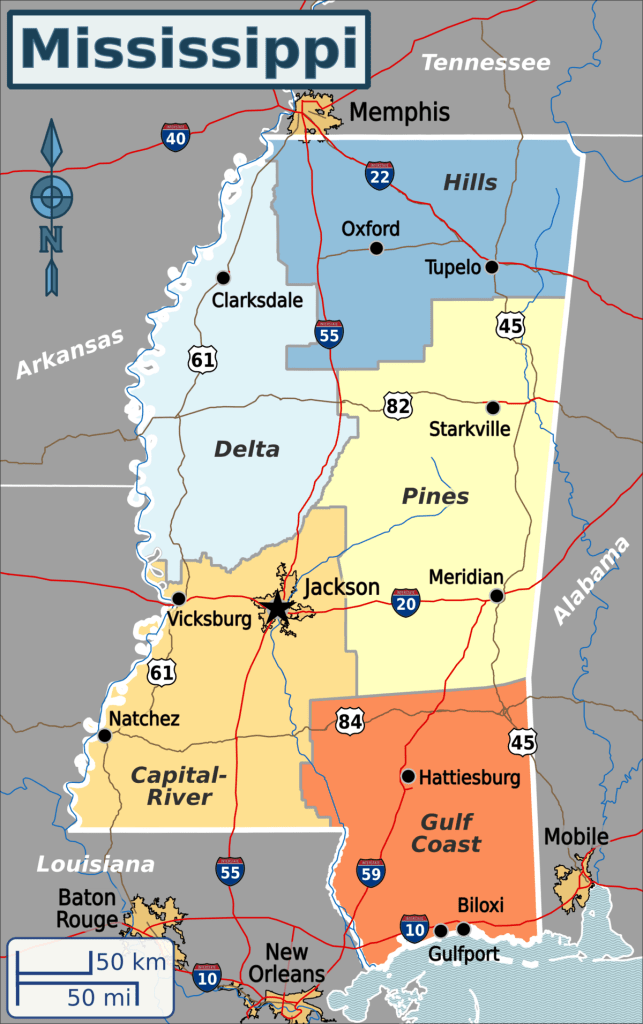

Mississippi hospitals are dying without Medicaid expansion

https://mailchi.mp/c6914989575d/the-weekly-gist-march-31-2023?e=d1e747d2d8

Published this week in the New York Times, this article describes the decaying state of Greenwood Leflore Hospital, a 117 year-old facility in the Mississippi Delta that may be within months of closure. While rural hospitals across the country are struggling, Mississippi’s firm opposition to Medicaid expansion has exacerbated the problem in that state, by depriving providers of an additional $1.4B per year in federal funds. Instead, only a few of the state’s 100-plus hospitals actually turn an annual profit, and uncompensated care costs are almost 10 percent of the average hospital’s operating costs.

Despite a dozen or more hospitals at imminent risk of closure, Mississippi officials would rather use the state’s $3.9B budget surplus to lower or eliminate the state income tax.

The Gist: Expanding Medicaid doesn’t just reduce rates of uncompensated care provided by hospitals, it changes the volume and type of care they provide.

Further, Medicaid expansion has been found to result in significant reductions in all-cause mortality.

Ensuring that low-income residents in Mississippi and other non-expansion states have access to Medicaid would allow providers to administer more preventive care and manage chronic diseases more effectively, before costly exacerbations require hospitalization.

Razor-thin hospital margins become the new normal

Hospital finances are starting to stabilize as razor-thin margins become the new normal, according to Kaufman Hall’s latest “National Flash Hospital Report,” which is based on data from more than 900 hospitals.

External economic factors including labor shortages, higher material expenses and patients increasingly seeking care outside of inpatient settings are affecting hospital finances, with the high level of fluctuation that margins experienced since 2020 beginning to subside.

Hospitals’ median year-to-date operating margin was -1.1 percent in February, down from -0.8 percent in January, according to the report. Despite the slight dip, February marked the eight month in which the variation in month-to-month margins decreased relative to the last three years.

“After years of erratic fluctuations, over the last several months we are beginning to see trends emerge in the factors that affect hospital finances like labor costs, goods and services expenses and patient care preferences,” Erik Swanson, senior vice president of data and analytics with Kaufman Hall, said. “In this new normal of razor thin margins, hospitals now have more reliable information to help make the necessary strategic decisions to chart a path toward financial security.”

High expenses continued to eat into hospitals’ bottom lines, with February signaling a shift from labor to goods and services as the main cost driver behind hospital expenses. Inflationary pressures increased non-labor expenses by 6 percent year over year, but labor expenses appear to be holding steady, suggesting less dependence on contract labor, according to Kaufman Hall.

“Hospital leaders face an existential crisis as the new reality of financial performance begins to set in,” Mr. Swanson said. “2023 may turn out to be the year hospitals redefine their goals, mission, and idea of success in response to expense and revenue challenges that appear to be here for the long haul.”