Category Archives: Leadership Will

When Financial Performance Matters

https://www.kaufmanhall.com/insights/thoughts-ken-kaufman/when-financial-performance-matters

The Sunk Cost Fallacy

In behavioral economics, the sunk cost fallacy describes the tendency to carry on with a project or investment past the point where cold logic would suggest it is not working out. Given human nature, the existence of the sunk cost fallacy is not surprising. The more resources—time, money, emotions—we devote to an effort, the more we want it to succeed, especially when the cause is an important one.

Under normal circumstances, the sunk cost fallacy might qualify as an interesting but not especially important economic theory. But at the moment, given that 2022 will likely be the worst financial year for hospitals since 2008 and given that the hospital revenue/expense relationship seems to be entirely broken, there is little that is theoretical about the sunk cost fallacy. Instead, the sunk cost fallacy becomes one of the most important action ideas in the hospital industry’s absolutely necessary financial recovery.

Historically, cases of the sunk cost fallacy can be relatively easy to spot. However, in real time, cases can be hard to identify and even harder to act on. For hospital organizations that are subsidizing underperforming assets, identifying and acting on these cases is now essential to the financial health of most hospital enterprises.

For example, perhaps the asset that is underperforming is a hospital acquired by a health system. (Although this same concept could apply to a service line or a related service such as a skilled nursing facility, ambulatory surgery center, or imaging center.) The costs associated with integrating an acquired hospital into a health system are typically significant. And chances are, if the hospital was struggling prior to the acquisition, the purchaser made substantial capital investments to improve the performance.

As time goes on, if the financial performance of the entity in question continues to fall short, hospital executives may be reluctant to divest the asset because of their heavy investment in it.

This understandable tendency can lead the acquiring organization to throw good money after bad. After all, even when an asset is underperforming, it can’t be allowed to deteriorate. In the case of hospitals, that’s not just a matter of keeping weeds from sprouting in the parking lot. The health system often winds up supporting an underperforming hospital with both working capital and physical capital, which compounds the losses.

And the costs don’t stop there, because other assets in the system are supporting the underperforming asset. This de facto cross-subsidy has been commonplace in hospital organizations for decades. Such a cross subsidy was probably never sustainable, but it is even less so in the current challenging financial environment.

This is a transformative period in American healthcare, when hospital organizations are faced with the need to fundamentally reinvent themselves both financially and clinically. The opportunity costs of supporting assets that don’t have an appropriate return are uniquely high in such an environment. This is true whether the underperforming asset is a hospital in a smaller system, multiple hospitals in a larger system, or a service line within a hospital.

The money that is being funneled off to support underperforming assets may be better directed, for example, toward realigning the organization’s portfolio away from inpatient care and toward growth strategies. In some cases, the resources may be needed for more immediate purposes, such as improving cash flow to support mission priorities and avoiding downgrades of the organization’s credit rating.

The underlying principle is straightforward:

When a hospital supports too many low-performing assets, the capital allocation process becomes inefficient. Directing working capital and capital capacity toward assets that are dilutive to long-term financial success means that assets that are historically or potentially accretive don’t receive the resources they need to grow and thrive. The underlying principle is a clear lose-lose.

In the highly challenging current environment, it is especially important for boards and management to recognize the sunk cost fallacy and determine the right size of their hospital organizations—both clinically and financially.

Some leadership teams may determine that their organizations are too big, or too big in the wrong places, and need to be smaller in order to maximize clinical and balance-sheet strength. Other leadership teams may determine that their organizations are not large enough to compete effectively in their fast-changing markets or in a fast-changing economy.

Organizational scale is a strategy that must be carefully managed. A properly sized organization maximizes its chances of financial success in this very difficult inflationary period. Such an organization invests consistently in its best performing assets and reduces cross-subsidies to services and products that have outlived their opportunity for clinical or financial success.

Executives may see academic economic theory as arcane and not especially relevant. However, we have clearly entered a financial moment when paying attention to the sunk cost fallacy will be central to maintaining, or recovering, the financial, clinical, and mission strength of America’s hospitals.

The Hospital Makeover—Part 2

America’s hospitals have a $104 billion problem.

That’s the amount you arrive at if you multiply the number of physicians employed by hospitals and health systems (approximately 341,200 as of January 2022, according to data from the Physicians Advocacy Institute and Avalere) by the median $306,362 subsidy—or loss—reported in our Q1 2023 Physician Flash Report.

Subsidizing physician employment has been around for a long time and such subsidies were historically justified as a loss leader for improved clinical services, the potential for increased market share, and the strengthening of traditionally profitable services.

But I am pretty sure the industry did not have $104 billion in losses in mind when the physician employment model first became a key strategic element in the hospital operating model. However, the upward reset in expenses brought on by the pandemic and post-pandemic inflation has made many downstream hospital services that historically operated at a profit now operate at breakeven or even at a loss. The loss leader physician employment model obviously no longer works when it mostly leads to more losses.

This model is clearly broken and in demand of a near-term fix. Perhaps the critical question then is how to begin? How to reconsider physician employment within the hospital operating plan?

Out of the box, rethink the physician productivity model. Our most recent Physician Flash Report data shows that for surgical specialties, there was a median $77 net patient revenue per provider wRVU. For the same specialties, there was a median $80 provider paid compensation per provider wRVU. In other words, before any other expenses are factored in, these specialties are losing $3 per wRVU on paid compensation alone. Getting providers to produce more wRVUs only makes the loss bigger.

It’s the classic business school 101 problem.

If a factory is losing $5 on every widget it produces, the answer is not to produce more widgets. Rather, expenses need to come down, whether that is through a readjustment of compensation, new compensation models that reward efficiency, or the more effective use of advanced practice providers.

Second, a number of hospital CEOs have suggested to me that the current employed physician model is quite past its prime. That model was built for a system of care that included generally higher revenues, more inpatient care, and a greater proportion of surgical vs. medical admissions. But overall, these trends were changing and then were accelerated by the Covid pandemic. Inpatient revenue has been flat to down. More clinical work continues to shift to the outpatient setting and, at least for the time being, medical admissions have been more prominent than before the pandemic.

Taking all this into account suggests that in many places the employed physician organizational and operating model is entirely out of balance. One would offer the calculated guess that there are too many coaches on the team and not enough players on the field. This administrative overhead was seemingly justified in a different loss leader environment but now it is a major contributor to that $104 billion industry-wide loss previously calculated.

Finally, perhaps the very idea of physician employment needs to be rethought.

My colleagues Matthew Bates and John Anderson have commented that the “owner” model is more appealing to physicians who remain independent then the “renter” model. The current employment model offers physicians stability of practice and income but appears to come at the cost of both a loss of enthusiasm and lost entrepreneurship. The massive losses currently experienced strongly suggest that new models are essential to reclaim physician interest and establish physician incentives that result in lower practice expenses, higher practice revenues, and steadily reduced overall subsidies.

Please see this blog as an extension of my last blog, “America’s Hospitals Need a Makeover.” It should be obvious that by analogy we are not talking about a coat of paint here or even new appliances in the kitchen.

The financial performance of America’s hospitals has exposed real structural flaws in the healthcare house. A makeover of this magnitude is going to require a few prerequisites:

- Don’t start designing the renovation unless you know specifically where profitability has changed within your service lines and by explicitly how much. Right now is the time to know how big the problem is, where those problems are located, and what is the total magnitude of the fix.

- The Board must be brought into the discussion of the nature of the physician employment problem and the depth of its proposed solutions. Physicians are not just “any employees.” They are often the engine that runs the hospital and must be afforded a level of communication that is equal to the size of the financial problem. All of this will demand the Board’s knowledge and participation as solutions to the physician employment dilemma are proposed, considered, and eventually acted upon.

The basic rule of home renovation applies here as well: the longer the fix to this problem is delayed the harder and more expensive the project becomes. The losses set out here certainly suggest that physician employment is a significant contributing factor to hospitals’ current financial problems overall. It would be an understatement to say that the time to get after all of this is right now.

Is the Traditional Hospital Strategy Aging Out?

https://www.kaufmanhall.com/insights/thoughts-ken-kaufman/traditional-hospital-strategy-aging-out

On October 1, 1908, Ford produced the first Model T automobile. More than 60 years later, this affordable, mass produced, gasoline-powered car was still the top-selling automobile of all time. The Model T was geared to the broadest possible market, produced with the most efficient methods, and used the most modern technology—core elements of Ford’s business strategy and corporate DNA.

On April 25, 2018, almost 100 years later, Ford announced that it would stop making all U.S. internal-combustion sedans except the Mustang.

The world had changed. The Taurus, Fusion, and Fiesta were hardly exciting the imaginations of car-buyers. Ford no longer produced its U.S. cars efficiently enough to return a suitable profit. And the internal combustion technology was far from modern, with electronic vehicles widely seen as the future of automobiles.

Ford’s core strategy, and many of its accompanying products, had aged out. But not all was doom and gloom; Ford was doing big and profitable business in its line of pickups, SUVs, and -utility vehicles, led by the popular F-150.

It’s hard to imagine the level of strategic soul-searching and cultural angst that went into making the decision to stop producing the cars that had been the basis of Ford’s history. Yet, change was necessary for survival. At the time, Ford’s then-CEO Jim Hackett said, “We’re going to feed the healthy parts of our business and deal decisively with the areas that destroy value.”

So Ford took several bold steps designed to update—and in many ways upend—its strategy. The company got rid of large chunks of the portfolio that would not be relevant going forward, particularly internal combustion sedans. Ford also reorganized the company into separate divisions for electric and internal combustion vehicles. And Ford pivoted to the future by electrifying its fleet.

Ford did not fully abandon its existing strategies. Rather, it took what was relevant and successful, and added that to the future-focused pivot, placing the F-150 as the lead vehicle in its new electric fleet.

This need for strategic change happens to all large organizations. All organizations, including America’s hospitals and health systems, need to confront the fact that no strategic plan lasts forever.

Over the past 25-30 years, America’s hospitals and health systems based their strategies on the provision of a high-quality clinical care, largely in inpatient settings. Over time, physicians and clinics were brought into the fold to strengthen referral channels, but the strategic focus remained on driving volume to higher-acuity services.

More recently, the longstanding traditional patient-physician-referral relationship began to change. A smarter, internet-savvy, and self-interested patient population was looking for different aspects of service in different situations. In some cases, patients’ priority was convenience. In other cases, their priority was affordability. In other cases, patients began going to great lengths to find the best doctors for high-end care regardless of geographic location. In other cases, patients wanted care as close as their phone.

Around the country, hospitals and health systems have seen these environmental changes and adjusted their strategies, but for the most part only incrementally. The strategic focus remains centered on clinical quality delivered on campus, while convenience, access, value, affordability, efficiency, and many virtual innovations remain on the strategic periphery.

Health system leaders need to ask themselves whether their long-time, traditional strategy is beginning to age out. And if so, what is the “Ford strategy” for America’s health systems?

The questions asked and answered by Ford in the past five years are highly relevant to health system strategic planning at a time of changing demand, economic and clinical uncertainty, and rapid innovation. For example, as you view your organization in its entirety, what must be preserved from the existing structure and operations, and what operations, costs, and strategies must leave? And which competencies and capabilities must be woven into a going-forward structure?

America’s hospitals and health systems have an extremely long history—in some cases, longer than Ford’s. With that history comes a natural tendency to stick with deeply entrenched strategies. Now is the time for health systems to ask themselves, what is our Ford F150? And how do we “electrify” our strategic plan going forward?

Is ‘toxic positivity’ a healthcare problem? One CEO thinks so.

Writing for Forbes, Sachin Jain, president and CEO of SCAN Group and Health Plan, argues that “toxic positivity,” or the idea that one should only focus on what’s going right rather than identifying and working on the underlying causes of a problem, is rampant throughout the healthcare industry and offers a few ideas on how to fix it.

Toxic positivity in healthcare

Jain writes that toxic positivity is a “somewhat understandable reaction to seemingly insurmountable obstacles, which perhaps explains toxic positivity’s ascendancy in the healthcare industry.” But now, toxic positivity is “bleeding into situations involving challenging but fully solvable problems.”

For example, Jain writes that nearly every company in the healthcare industry eventually pays a marketing agency to craft “glorious-sounding mission statements” that are then used by leaders whenever they are confronted with their shortcomings.

“Your health system just christened a new billion-dollar hospital, but is unleashing bill collectors on the indigent? Our mission is clear: Patients first!” Jain writes. “Your startup appears to be serving only the wealthiest and healthiest retirees, while pulling no cost from the healthcare system? We’re proudly committed to doing right by seniors by offering value-based care!”

Jain clarifies that he doesn’t believe all healthcare executives are cynically trying to avoid hard issues. Rather, they are “often too far removed from the front lines of the system, and even their own companies’ patient-facing operations, to witness the flaws.”

Often executives don’t notice the flaws in their health systems until a loved one needs help, Jain writes. “Only then do the industry’s leaders confront the reality that, at a person’s most vulnerable point in life, healthcare companies often treat you like a consumer … instead of just taking care of you.”

Without that reality check, it’s easy for executives to rely on their lofty mission statements and value propositions, and to “see their companies as distinct from, rather than intrinsically connected to, the industry’s biggest issues,” Jain writes.

How to fix toxic positivity

One simple intervention won’t fix toxic positivity in the healthcare industry, Jain writes, but companies can start by talking about their flaws.

“In a perfect world, the healthcare industry would commit to a culture of relentless interrogation of its flaws as a means of driving to better results,” Jain writes. Healthcare leaders need to “stop hiding behind company mission statements and ‘just-so stories’ about their impact and start speaking publicly about the steep challenges we each face as we fall short of fulfilling our specific corporate mission,” Jain adds. That means publicly addressing issues at events and discussing strategies for addressing them.

Private behavior within a company can also help reverse toxic positivity, Jain writes. Leaders should continue celebrating the accomplishments of frontline healthcare providers, but they should also “bring a critical eye to their operations and demand — not just encourage — that their colleagues help them uncover ways they can individually and collectively do better.”

That means asking questions like, “If our organization disappeared tomorrow and people were forced to find their healthcare insurance or services or devices elsewhere, would anyone be truly worse off and why?” Jain writes. If your company doesn’t have an answer for that, then you should work harder to increase your replacement value and drive competitive differentiation.

Addressing toxic positivity also means addressing the flaws in value-based care and having “honest, authentic conversations about what works and what doesn’t and why,” Jain writes. “About whether companies that proclaim to improve care are merely benefitting from arbitrage opportunities in reimbursement systems or are actually, meaningfully improving service to patients.”

Executives need to stop treating the healthcare industry like all other industries and “call BS on the idea that it’s somehow okay to be financially successful without making an actual difference in anyone’s lives,” Jain writes.

The healthcare industry needs to welcome thoughtful, critical, and reflective voices to every table, Jain writes. “Because nothing — absolutely nothing — will actually get better without them.”

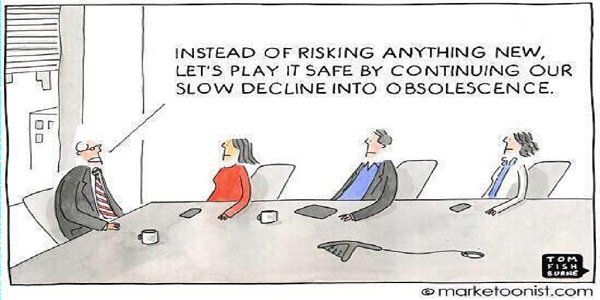

Cartoon – Status Quo Strategy

Former patient kills his surgeon and three others at a Tulsa hospital

https://mailchi.mp/31b9e4f5100d/the-weekly-gist-june-03-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

On Wednesday afternoon, an aggrieved patient shot and killed four people, including his orthopedic surgeon and another doctor, at a Saint Francis Hospital outpatient clinic, before killing himself. The gunman, who blamed his surgeon for ongoing pain after a recent back surgery, reportedly purchased his AR-15-style rifle only hours before the mass shooting, which also injured 10 others. The same day as this horrific attack, an inmate receiving care at Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton, OH shot and killed a security guard, and then himself.

The Gist: On the heels of the horrendous mass shootings in Buffalo and Uvalde, we find ourselves grappling with yet more senseless gun violence. Last week, we called on health system leaders to play a greater role in calling for gun law reforms. This week’s events show they must also ensure that their providers, team members, and patients are safe.

Of course, that’s a tall order, as hospital campuses are open for public access, and strive to be convenient and welcoming to patients. Most health systems already staff armed security guards or police officers, have a limited number of unlocked entrances, and provide active shooter training for staff.

This week’s events remind us that our healthcare workers are not just on the front lines of dealing with the horrific outcomes of gun violence, but may find themselves in the crosshairs—adding to already rising levels of workplace violence sparked by the pandemic.

Something must change.

Gun violence, the leading cause of death among US children, claims more victims

https://mailchi.mp/d73a73774303/the-weekly-gist-may-27-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

Only 10 days after a racially motivated mass shooting that killed 10 in a Buffalo, NY grocery store, 19 children and two teachers were murdered on Tuesday at an elementary school in Uvalde, TX. The Uvalde shooting was the 27th school shooting, and one of over 212 mass shootings, that have occurred this year alone.

Firearms recently overtook car accidents as the leading cause of childhood deaths in the US, and more than 45,000 Americans die from gun violence each year.

The Gist: Gun violence is, and has long been, a serious public health crisis in this country. It is both important to remember, yet difficult for some to accept, that many mass shootings are preventable.

Health systems, as stewards of health in their communities, can play a central role in preventing gun violence at its source, both by bolstering mental health services and advocating for the needed legislative actions—supported by a strong majority of American voters—to stem this public health crisis.

As Northwell Health CEO Michael Dowling said this week, “Our job is to save lives and prevent people from illness and death. Gun violence is not an issue on the outside—it’s a central public health issue for us. Every single hospital leader in the United States should be standing up and screaming about what an abomination this is. If you were hesitant about getting involved the day before…May 24 should have changed your perspective. It’s time.”

The MacArthur Tenets

https://www.leadershipnow.com/macarthurprinciples.html

Douglas MacArthur was one of the finest military leaders the United States ever produced. John Gardner, in his book On Leadership described him as a brilliant strategist, a farsighted administrator, and flamboyant to his fingertips. MacArthur’s discipline and principled leadership transcended the military. He was an effective general, statesman, administrator and corporate leader.

William Addleman Ganoe recalled in his 1962 book, MacArthur Close-up: An Unauthorized Portrait, his service to MacArthur at West Point. During World War II, he created a list of questions with General Jacob Devers, they called The MacArthur Tenets. They reflect the people-management traits he had observed in MacArthur. Widely applicable, he wrote, “I found all those who had no troubles from their charges, from General Sun Tzu in China long ago to George Eastman of Kodak fame, followed the same pattern almost to the letter.”![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Do I heckle my subordinates or strengthen and encourage them?

Do I heckle my subordinates or strengthen and encourage them?

![]() Do I use moral courage in getting rid of subordinates who have proven themselves beyond doubt to be unfit?

Do I use moral courage in getting rid of subordinates who have proven themselves beyond doubt to be unfit?

![]() Have I done all in my power by encouragement, incentive and spur to salvage the weak and erring?

Have I done all in my power by encouragement, incentive and spur to salvage the weak and erring?

![]() Do I know by NAME and CHARACTER a maximum number of subordinates for whom I am responsible? Do I know them intimately?

Do I know by NAME and CHARACTER a maximum number of subordinates for whom I am responsible? Do I know them intimately?

![]() Am I thoroughly familiar with the technique, necessities, objectives and administration of my job?

Am I thoroughly familiar with the technique, necessities, objectives and administration of my job?

![]() Do I lose my temper at individuals?

Do I lose my temper at individuals?

![]() Do I act in such a way as to make my subordinates WANT to follow me?

Do I act in such a way as to make my subordinates WANT to follow me?

![]() Do I delegate tasks that should be mine?

Do I delegate tasks that should be mine?

![]() Do I arrogate everything to myself and delegate nothing?

Do I arrogate everything to myself and delegate nothing?

![]() Do I develop my subordinates by placing on each one as much responsibility as he can stand?

Do I develop my subordinates by placing on each one as much responsibility as he can stand?

![]() Am I interested in the personal welfare of each of my subordinates, as if he were a member of my family?

Am I interested in the personal welfare of each of my subordinates, as if he were a member of my family?

![]() Have I the calmness of voice and manner to inspire confidence, or am I inclined to irascibility and excitability?

Have I the calmness of voice and manner to inspire confidence, or am I inclined to irascibility and excitability?

![]() Am I a constant example to my subordinates in character, dress, deportment and courtesy?

Am I a constant example to my subordinates in character, dress, deportment and courtesy?

![]() Am I inclined to be nice to my superiors and mean to my subordinates?

Am I inclined to be nice to my superiors and mean to my subordinates?

![]() Is my door open to my subordinates?

Is my door open to my subordinates?

![]() Do I think more of POSITION than JOB?

Do I think more of POSITION than JOB?

![]() Do I correct a subordinate in the presence of others?

Do I correct a subordinate in the presence of others?

Can we take the long view on physician strategy?

https://mailchi.mp/d57e5f7ea9f1/the-weekly-gist-january-21-2022?e=d1e747d2d8

It feels like a precarious moment in health systems’ relationships with their doctors. The pandemic has accelerated market forces already at play: mounting burnout, the retirement of Baby Boomer doctors, pressure to grow virtual care, and competition from well-funded insurers, investors and disruptors looking to build their own clinical workforces.

Many health systems have focused system strategy around deepening consumer relationships and loyalty, and quite often we’re told that physicians are roadblocks to consumer-centric offerings (problematic since doctors hold the deepest relationships with a health system’s patients).

When debriefing with a CEO after a health system board meeting, we pointed out the contrast between the strategic level of discussion of most of the meeting with the more granular dialogue around physicians, which focused on the response to a private equity overture to a local, nine-doctor orthopedics practice. It struck us that if this level of scrutiny was applied to other areas, the board would be weighing in on menu changes in food services or selecting throughput metrics for hospital operating rooms.

The CEO acknowledged that while he and a small group of physician leaders have tried to focus on a long-term physician network strategy, “it has been impossible to move beyond putting out the ‘fire of the week’—when it comes to doctors, things that should be small decisions rise to crisis level, and that makes it impossible to play the long game.”

It’s obvious why this happens: decisions involving a small number of doctors can have big implications for short-term, fee-for-service profits, and for the personal incomes of the physicians involved. But if health systems are to achieve ambitious goals, they must find a way to play the long game with their doctors, enfranchising them as partners in creating strategy, and making (and following through on) tough decisions. If physician and system leaders don’t have the fortitude to do this, they’ll continue to find that doctors are a roadblock to transformation.