Trump says Covid-19 is ‘dying out.’ Experts fear his dismissiveness could prolong the crisis

The White House is taking a new position on the coronavirus pandemic: a daily count of 750 deaths is a testament to the federal government’s successful pandemic response.

On Wednesday, when U.S. health officials reported nearly 27,000 new Covid-19 cases, President Trump said in a television interview that the virus was “dying out.” He brushed off concerns about an upcoming rally in Tulsa, Okla., because the number of cases there is “very miniscule,” despite the state’s surging infection rate. In a Wall Street Journal interview Wednesday, Trump argued coronavirus testing was “overrated” because it reveals large numbers of new Covid-19 cases, which in turn “makes us look bad,” and suggested that some Americans who wear masks do so not only to guard against the virus, but perhaps to display their anti-Trump animus.

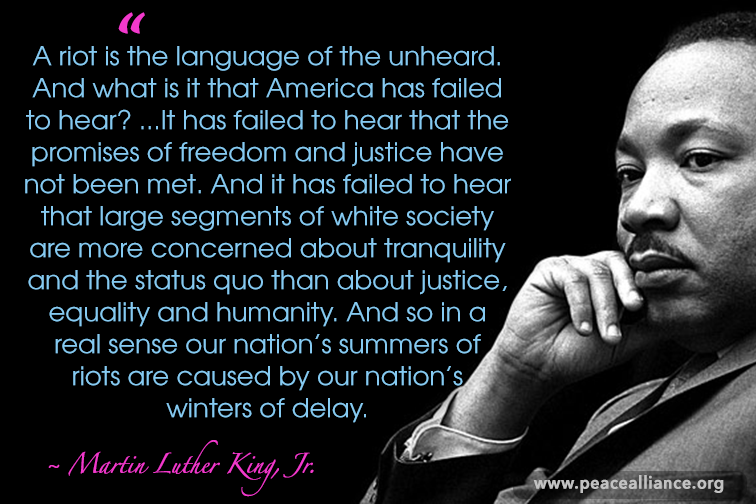

But a range of public health experts told STAT that this messaging not only diverts attention from a pandemic that has already caused 120,000 U.S. deaths, but has more practical implications: It could make it difficult for local governments to enlist the public in the mitigation measures necessary to reduce the continued spread of the virus.

“The science behind how people process public warnings in a crisis supports this: You have to have people speaking with one voice,” said Monica Schoch-Spana, a medical anthropologist at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “You need a chorus.”

Conflicting directives can make it more difficult for recommendations coming from state and local leaders to have an impact, said Sara Bleich, a professor of public health policy at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

“It sends a mixed message, which is confusing, particularly because while many people will get infected, most will not get severely sick, so it’s easy to say this won’t happen to me,” she said. “And it’s that sort of attitude that will keep us in this situation for a very long time.”

While the president has for weeks, if not months, underplayed the pandemic, his sharp and repeated remarks this week represent a remarkable attempt from the leader of American government to effectively declare the U.S. Covid-19 epidemic over.

The president’s rhetoric comes at a time that his coronavirus task force, which once conducted daily briefings, has not addressed the public since May. The president’s resumption of campaign rallies flouts federal guidance that encourages mask use (Trump’s campaign will hand out masks and hand sanitizer at the rally, but has not said it will require attendees to use them) and discourages large indoor gatherings. And the president has repeatedly claimed, misleadingly, that persistently high U.S. case totals are simply the result of increased testing.

Health experts say that political leaders preaching caution and modeling proper behavior — such as wearing a mask and demonstrating proper hand hygiene — can send a powerful signal to people that these steps can not only protect them, but their communities. They say that, essentially, national and state leaders need to walk the walk in a situation when individual behavior, like staying home when sick and cooperating with contact tracing, can make a large impact in curbing contagion.

Trump’s counterproductive behavior, Schoch-Spana said, extends far beyond the consistently dismissive tone he has taken toward the health risks of Covid-19. With few exceptions, the president has refused to wear a mask in public, and has insisted on continuing in-person briefings and White House events that effectively defy federal health guidance about gathering indoors in large groups.

“It’s not just words, it’s actions,” she said. “So when you have the nation’s top executive refusing to wear a mask, holding meetings where people are shoulder to shoulder, where he’s signing executive orders — that is also a form of communication.”

Experts also say continued federal commitments to combating the virus are crucial as the public grows tired of abatement measures. Instead, Trump has only elevated his monthslong campaign of downplaying the virus.

And Vice President Mike Pence, in a Wall Street Journal op-ed, framed the declines in cases and deaths since April as “testament to the leadership of President Trump” — even as hundreds of Americans are still dying every day and cases are not dropping further.

Rep. Donna Shalala (D-Fla.), who served as health secretary during the Clinton administration, said she hoped Americans would listen to public health guidance from local officials, not Trump and Pence.

“The president of the United States is dangerous to the health of the people of my district, because he’s giving out misinformation and false hope,” she said. “For those that believe him, they’re putting themselves and their families at risk.”

Public health experts have raised a number of issues with the administration’s messaging.

For one, a plateau of cases and deaths should not be celebrated, they say. While some countries in Europe and Asia have not only flattened their curve but driven them down, that hasn’t happened in the United States. Daily cases and deaths dipped from the peak in April, but have averaged about 20,000 and 800, respectively, for weeks.

Beyond those numbers representing real people getting sick and dying, there are other problems with sustained high levels of spread. The more cases there are, the more difficult it is for the surveillance system, including contact tracing, to keep up. It’s also more likely that some of the cases will spiral into explosive spread; 20,000 cases can turn into 40,000 a lot faster than one case can turn into 20,000.

Plus, a failure to suppress spread now could lead to more prolonged disruptions to daily life. If transmission rates come fall are still what they are now in certain communities, that makes it harder to reopen schools, for example.

Experts also point to evidence suggesting that the daily case and death numbers won’t stay flat for long. While new cases in the Northeast and Midwest are declining, a number of states in the West and South — Arizona, Texas, Florida, California, and Oregon among them — have reported record number of new cases this week. What worries public health officials is that, without measures to stem those increases, those outbreaks could keep growing. Those thousands of new cases also signal that, in a week or two, some portion of those people will show up in the hospital, and, about a week after that, a number of them will be dead, even as clinicians have learned more about treating severe Covid-19.

Some states in the South and West are already reporting record hospitalizations from Covid-19.

The White House’s shrug has been echoed by some governors, who insist, like Pence and Trump, that increased testing explains away the rise in cases. That is certainly one reason; testing has become more widespread, so states are capturing a more accurate reading of their true case burden.

But experts say increased testing can only account for some of the data states are reporting. Other metrics — including rising hospitalizations, filling ICUs, and the increasing rate of tests that are positive for the virus — signal broader spread.

Until Wednesday, leaders of Texas and Arizona also bristled at efforts from city and county officials to institute mask requirements, but acceded to growing pressure even as they have not ordered statewide mandates.

Cameron Wolfe, an infectious disease expert at Duke University, said he was seeing a growing “fatigue” among the public to keep up with precautionary steps like physical distancing and mask wearing. People letting down their guard was coinciding with an increase of cases in states, including North Carolina.

He said medical experts and health workers needed to model proper behavior to show others that the coronavirus epidemic was still something that required action. But, he added, “that also comes from political leaders buying into this.”

Federal and state authorities, he said, need to be “taking this to heart. That has not yet happened. That needs to change if we’re going to get people to buy into this.”