Cartoon – Sign of the Times (Health Plan)

Just as other industries are rolling back some consumer-friendly changes made early in the pandemic — think empty middle seats on airplanes — so, too, are health insurers.

Many voluntarily waived all deductibles, copayments and other costs for insured patients who fell ill with covid-19 and needed hospital care, doctor visits, medications or other treatment.

Setting aside those fees was a good move from a public relations standpoint. The industry got credit for helping customers during tough times. And it had political and financial benefits for insurers, too.

But nothing lasts forever.

Starting at the end of last year — and continuing into the spring — a growing number of insurers are quietly ending those fee waivers for covid treatment on some or all policies.

“When it comes to treatment, more and more consumers will find that the normal course of deductibles, copayments and coinsurance will apply,” said Sabrina Corlette, research professor and co-director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University.

Even so, “the good news is that vaccinations and most covid tests should still be free,” added Corlette.

That’s because federal law requires insurers to waive costs for covid testing and vaccination.

Guidance issued early in President Joe Biden’s term reinforced that Trump administration rule about waiving cost sharing for testing and said it applies even in situations in which an asymptomatic person wants a test before, say, visiting a relative.

But treatment is different.

Insurers voluntarily waived those costs, so they can decide when to reinstate them.

Indeed, the initial step not to charge treatment fees may have preempted any effort by the federal government to mandate it, said Cynthia Cox, a vice president at KFF and director for its program on the Affordable Care Act.

In a study released in November, researchers found about 88% of people covered by insurance plans — those bought by individuals and some group plans offered by employers — had policies that waived such payments at some point during the pandemic, said Cox, a co-author. But many of those waivers were expected to expire by the end of the year or early this year.

Some did.

Anthem, for example, stopped them at the end of January. UnitedHealth, another of the nation’s largest insurers, began rolling back waivers in the fall, finishing up by the end of March. Deductible-free inpatient treatment for covid through Aetna expired Feb. 28.

A few insurers continue to forgo patient cost sharing in some types of policies. Humana, for example, has left the cost-sharing waiver in place for Medicare Advantage members, but dropped it Jan. 1 for those in job-based group plans.

Not all are making the changes.

For example, Premera Blue Cross in Washington and Sharp Health Plan in California have extended treatment cost waivers through June. Kaiser Permanente said it is keeping its program in place for members diagnosed with covid and has not set an end date. Meanwhile, UPMC in Pittsburgh planned to continue to waive all copayments and deductibles for in-network treatment through April 20.

What It All Means

Waivers may result in little savings for people with mild cases of covid that are treated at home. But the savings for patients who fall seriously ill and wind up in the hospital could be substantial.

Emergency room visits and hospitalization are expensive, and many insured patients must pay a portion of those costs through annual deductibles before full coverage kicks in.

Deductibles have been on the rise for years. Single-coverage deductibles for people who work for large employers average $1,418, while those for employees of small firms average $2,295, according to a survey of employers by KFF. (KHN is an editorially independent program of KFF.)

Annual deductibles for Affordable Care Act plans are generally higher, depending on the plan type.

Both kinds of coverage also include copayments, which are flat-dollar amounts, and often coinsurance, which is a percentage of the cost of office visits, hospital stays and prescription drugs.

Ending the waivers for treatment “is a big deal if you get sick,” said Robert Laszewski, an insurance industry consultant in Maryland. “And then you find out you have to pay $5,000 out-of-pocket that your cousin didn’t two months ago.”

Costs and Benefits

Still, those patient fees represent only a slice of the overall cost of caring for a hospitalized patient with covid.

While it helped patients’ cash flow, insurers saw other kinds of benefits.

For one thing, insurers recognized early on that patients — facing stay-at-home orders and other restrictions — were avoiding medical care in droves, driving down what insurers had to fork out for care.

“I think they were realizing they would be reporting extraordinarily good profits because they could see utilization dropping like a rock,” said Laszewski. “Doctors, hospitals, restaurants and everyone else were in big trouble. So, it was good politics to waive copays and deductibles.”

Besides generating goodwill, insurers may benefit in another way.

Under the ACA, insurers are required to spend at least 80% of their premium revenue on direct health care, rather than on marketing and administration. (Large group plans must spend 85%.)

By waiving those fees, insurers’ own spending went up a bit, potentially helping offset some share of what are expected to be hefty rebates this summer. That’s because insurers whose spending on direct medical care falls short of the ACA’s threshold must issue rebates by Aug. 1 to the individuals or employers who purchased the plans.

A record $2.5 billion was rebated for policies in effect in 2019, with the average rebate per person coming in at about $219.

Knowing their spending was falling during the pandemic helped fuel decisions to waive patient copayments for treatment, since insurers knew “they would have to give this money back in one form or another because of the rebates,” Cox said.

It’s a mixed bag for consumers.

“If they completely offset the rebates through waiving cost sharing, then it strictly benefits only those with covid who needed significant treatment,” noted Cox. “But, if they issue rebates, there’s more broad distribution.”

Even with that, insurers can expect to send a lot back in rebates this fall.

In a report out this week, KFF estimated that insurers may owe $2.1 billion in rebates for last year’s policies, the second-highest amount issued under the ACA. Under the law, rebate amounts are based on three years of financial data and profits. Final numbers aren’t expected until later in the year.

The rebates “are likely driven in part by suppressed health care utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic,” the report says.

Still, economist Joe Antos at the American Enterprise Institute says waiving the copays and deductibles may boost goodwill in the public eye more than rebates. “It’s a community benefit they could get some credit for,” said Antos, whereas many policyholders who get a small rebate check may just cash it and “it doesn’t have an impact on how they think about anything.”

https://mailchi.mp/da8db2c9bc41/the-weekly-gist-april-23-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

Given regulatory barriers and structural differences in practice, private equity firms have been slow to acquire and roll up physician practices and other care assets in other countries in the same way they’ve done here in the US. But according a fascinating piece in the Financial Times, investors have targeted a different healthcare segment, one ripe for the “efficiencies” that roll-ups can bring—small veterinary practices in the UK and Ireland.

British investment firm IVC bought up hundreds of small vet practices across the UK, only to be acquired itself by Swedish firm Evidensia, which is now the largest owner of veterinary care sites, with more than 1,500 across Europe. Vets describe the deals as too good to refuse: one who sold his practice to IVC said “he ‘almost fell off his chair’ on hearing how much it was offering. The vet, who requested anonymity, says IVC mistook his shock for hesitation—and increased its offer.” (Physician executives in the US, take note.) IVC claims that its model provides more flexible options, especially for female veterinarians seeking more work-life balance than offered by the typical “cottage” veterinary practice.

But consumers have complained of decreased access to care as some local clinics have been shuttered as a result of roll-ups. Meanwhile prices, particularly for pet medications like painkillers or feline insulin, have risen as much as 40 percent—and vets aren’t given leeway to offer the discounts they previously extended to low-income customers. And with IVC attaining significant market share in some communities (for instance, owning 17 of 32 vet practices in Birmingham), questions have arisen about diminished competition and even price fixing.

The playbook for private equity is consistent across human and animal healthcare: increase leverage, raise prices for care, and slash practice costs, all with little obvious value for consumers. It remains to be seen whether and how consumers will push back—either on behalf of their beloved pets, or for the sake of their own health.

https://mailchi.mp/da8db2c9bc41/the-weekly-gist-april-23-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

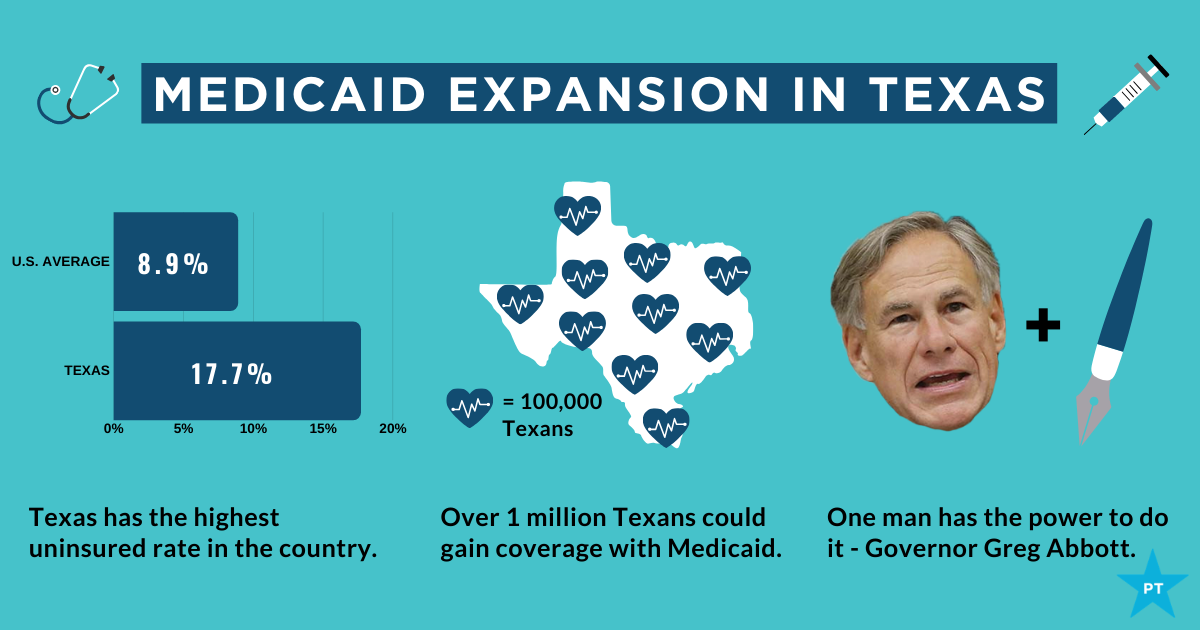

The showdown between the Biden administration and the state of Texas over Medicaid expansion continued to escalate this week. Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) said he planned to place a hold on the confirmation of Chiquita Brooks-LaSure to become Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), until his concerns over the agency’s move last week to rescind a waiver extension previously granted by the Trump administration were addressed.

The so-called “1115 waiver”—worth more than $11B annually—would have extended by a decade Texas’ ability to use Medicaid funds to cover hospital costs for uninsured residents, rather than expanding Medicaid coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). In rescinding the waiver extension, the Biden administration cited the lack of a public notice process before the waiver was granted, and said that the state’s existing waiver would instead expire next year, as previously scheduled.

Sources inside the administration told the Washington Post last week that the move was intended to force Texas’ hand on Medicaid expansion; the state is one of 12 that have not expanded Medicaid, leaving it with the largest share of uninsured residents of any state, with eligibility currently limited to pregnant women, children, people with disabilities, and families with monthly incomes under $300 per month, or 13.6 percent of the federal poverty level.

Enticing the dozen remaining holdout states to expand Medicaid is an important policy priority for the new administration. A key component of the recently passed American Rescue Plan Act is a package of enhanced incentives for those states to expand eligibility, offering an extended 90 percent federal match, in addition to increased funding for existing Medicaid populations.

Although none of the non-expansion states have budged yet, there has been renewed focus among state lawmakers on Medicaid expansion, including in Texas, where the idea had garnered bipartisan support. However, on Thursday, the Texas legislature voted down a proposal aimed at pushing the state toward expanding coverage for the uninsured, by an 80-68 margin. Meanwhile, the rescission of Texas’ waiver has angered the state’s Republican leadership, along with the Texas Hospital Association, whose members have benefited from the waiver’s use of funds to reimburse them for delivering uncompensated care.

While Cornyn’s hold will not ultimately stop the confirmation of the new CMS leader, the escalation on both sides over the past several days surely makes finding a compromise solution less likely. The Biden health policy team is said to be developing a new proposal, as part of an upcoming legislative package, to use the ACA marketplace to offer coverage to people in non-expansion states who might otherwise be eligible for Medicaid—yet another attempt to address one of the longest-standing points of contention stemming from the 2010 health reform law.

The Medicaid showdown is far from over.

The complexity of Medicare Advantage (MA) physician networks has been well-documented, but the payment regulations that underlie these plans remain opaque, even to experts. If an MA plan enrollee sees an out-of-network doctor, how much should she expect to pay?

The answer, like much of the American healthcare system, is complicated. We’ve consulted experts and scoured nearly inscrutable government documents to try to find it. In this post we try to explain what we’ve learned in a much more accessible way.

Medicare Advantage Basics

Medicare Advantage is the private insurance alternative to traditional Medicare (TM), comprised largely of HMO and PPO options. One-third of the 60+ million Americans covered by Medicare are enrolled in MA plans. These plans, subsidized by the government, are governed by Medicare rules, but, within certain limits, are able to set their own premiums, deductibles, and service payment schedules each year.

Critically, they also determine their own network extent, choosing which physicians are in- or out-of-network. Apart from cost sharing or deductibles, the cost of care from providers that are in-network is covered by the plan. However, if an enrollee seeks care from a provider who is outside of their plan’s network, what the cost is and who bears it is much more complex.

Provider Types

To understand the MA (and enrollee) payment-to-provider pipeline, we first need to understand the types of providers that exist within the Medicare system.

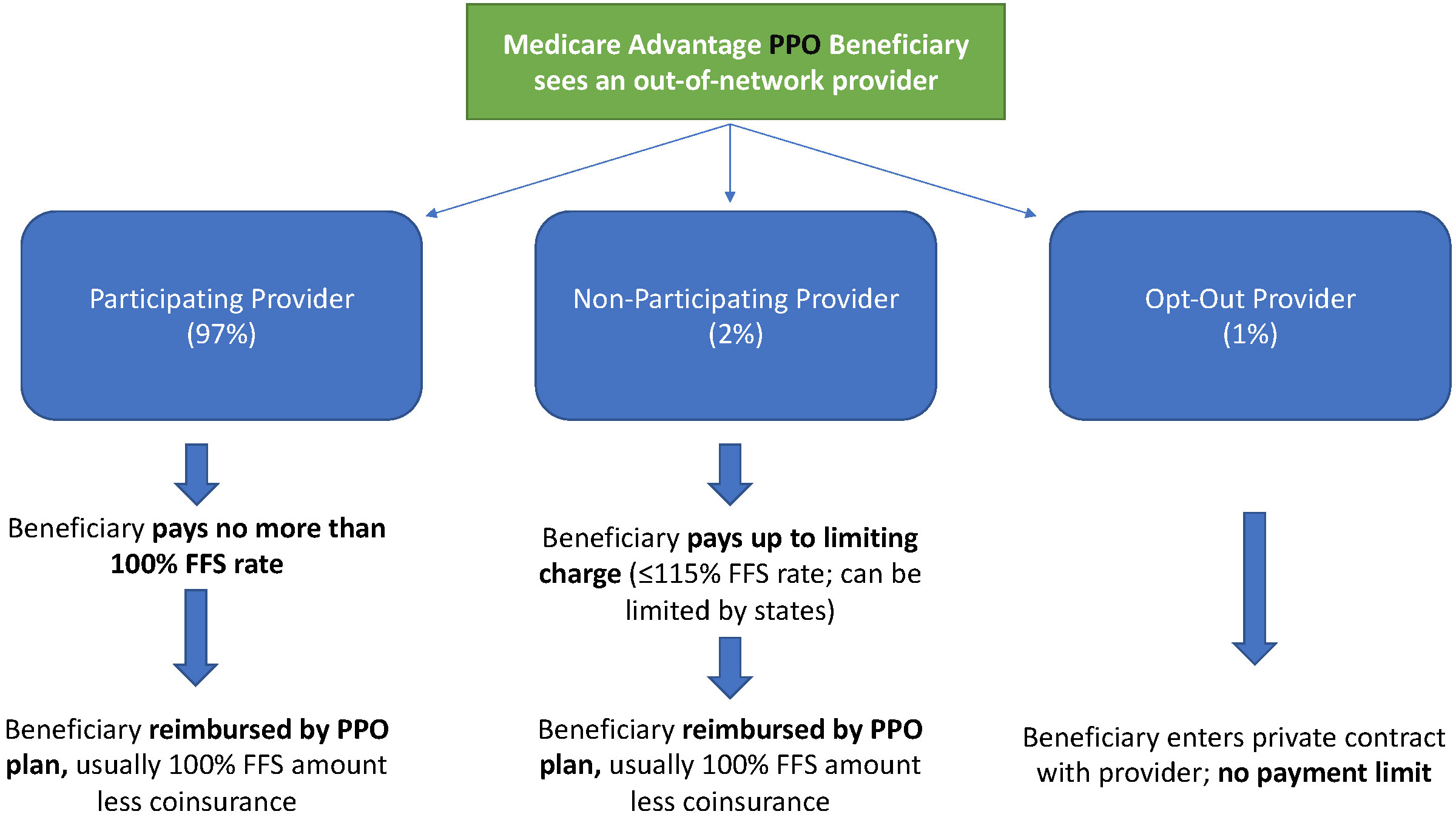

Participating providers, which constitute about 97% of all physicians in the U.S., accept Medicare Fee-For-Service (FFS) rates for full payment of their services. These are the rates paid by TM. These doctors are subject to the fee schedules and regulations established by Medicare and MA plans.

Non-participating providers (about 2% of practicing physicians) can accept FFS Medicare rates for full payment if they wish (a.k.a., “take assignment”), but they generally don’t do so. When they don’t take assignment on a particular case, these providers are not limited to charging FFS rates.

Opt-out providers don’t accept Medicare FFS payment under any circumstances. These providers, constituting only 1% of practicing physicians, can set their own charges for services and require payment directly from the patient. (Many psychiatrists fall into this category: they make up 42% of all opt-out providers. This is particularly concerning in light of studies suggesting increased rates of anxiety and depression among adults as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic).

How Out-of-Network Doctors are Paid

So, if an MA beneficiary goes to see an out-of-network doctor, by whom does the doctor get paid and how much? At the most basic level, when a Medicare Advantage HMO member willingly seeks care from an out-of-network provider, the member assumes full liability for payment. That is, neither the HMO plan nor TM will pay for services when an MA member goes out-of-network.

The price that the provider can charge for these services, though, varies, and must be disclosed to the patient before any services are administered. If the provider is participating with Medicare (in the sense defined above), they charge the patient no more than the standard Medicare FFS rate for their services. Non-participating providers that do not take assignment on the claim are limited to charging the beneficiary 115% of the Medicare FFS amount, the “limiting charge.” (Some states further restrict this. In New York State, for instance, the maximum is 105% of Medicare FFS payment.) In these cases, the provider charges the patient directly, and they are responsible for the entire amount (See Figure 1.)

Alternatively, if the provider has opted-out of Medicare, there are no limits to what they can charge for their services. The provider and patient enter into a private contract; the patient agrees to pay the full amount, out of pocket, for all services.

MA PPO plans operate slightly differently. By nature of the PPO plan, there are built-in benefits covering visits to out-of-network physicians (usually at the expense of higher annual deductibles and co-insurance compared to HMO plans). Like with HMO enrollees, an out-of-network Medicare-participating physician will charge the PPO enrollee no more than the standard FFS rate for their services. The PPO plan will then reimburse the enrollee 100% of this rate, less coinsurance. (See Figure 2.)

In contrast, a non-participating physician that does not take assignment is limited to charging a PPO enrollee 115% of the Medicare FFS amount, which can be further limited by state regulations. In this case, the PPO enrollee is also reimbursed by their plan up to 100% (less coinsurance) of the FFS amount for their visit. Again, opt-out physicians are exempt from these regulations and must enter private contracts with patients.

Some Caveats

There are two major caveats to these payment schemes (with many more nuanced and less-frequent exceptions detailed here). First, if a beneficiary seeks urgent or emergent care (as defined by Medicare) and the provider happens to be out-of-network for the MA plan (regardless of HMO/PPO status), the plan must cover the services at their established in-network emergency services rates.

The second caveat is in regard to the declared public health emergency due to COVID-19 (set to expire in April 2021, but likely to be extended). MA plans are currently required to cover all out-of-network services from providers that contract with Medicare (i.e., all but opt-out providers) and charge beneficiaries no more than the plan-established in-network rates for these services. This is being mandated by CMS to compensate for practice closures and other difficulties of finding in-network care as a result of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Outside of the pandemic and emergency situations, knowing how much you’ll need to pay for out-of-network services as a MA enrollee depends on a multitude of factors. Though the vast majority of American physicians contract with Medicare, the intersection of insurer-engineered physician networks and the complex MA payment system could lead to significant unexpected costs to the patient.

Share this…