This week, the House Energy and Commerce and Ways and Means Committees begins work on the reconciliation bill they hope to complete by Memorial Day. Healthcare cuts are expected to figure prominently in the committee’s work.

And in San Diego, America’s Physician Groups (APG) will host its spring meeting “Kickstarting Accountable Care: Innovations for an Urgent Future” featuring Presidential historian Dorris Kearns Goodwin and new CMS Innovation Center Director Abe Sutton. Its focus will be the immediate future of value-based programs in Trump Healthcare 2.0, especially accountable care organizations (ACOs) and alternative payment models (APMs).

Central to both efforts is the administration’s mandate to reduce federal spending which it deems achievable, in part, by replacing fee for services with value-based payments to providers from the government’s Medicare and Medicaid programs.

The CMS Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is the government’s primary vehicle to test and implement alternative payment programs that reduce federal spending and improve the quality and effectiveness of services simultaneously.

Pledges to replace fee-for-service payments with value-based incentives are not new to Medicare. Twenty-five years ago, they were called “pay for performance” programs and, in 2010, included in the Affordable Care as alternative payment models overseen by CMMI.

But the effectiveness of APMs has been modest at best: of 50+ models attempted, only 6 proved effective in reducing Medicare spending while spending $5.4 billion on the programs. Few were adopted in Medicaid and only a handful by commercial payers and large self-insured employers. Critics argue the APMs were poorly structured, more costly to implement than potential shared savings payments and sometimes more focused on equity and DEI aims than actual savings.

The question is how the Mehmet Oz-Abe Sutten version of CMMI will approach its version of value-based care, given modest APM results historically and the administration’s focus on cost-cutting.

Context is key:

Recent efforts by the Trump Healthcare 2.0 team and its leadership appointments in CMS and CMMI point to a value-agenda will change significantly. Alternative payment models will be fewer and participation by provider groups will be mandated for several. Measures of quality and savings will be fewer, more easily measured and and standardized across more episodes of care. Financial risks and shared savings will be higher and regulatory compliance will be simplified in tandem with restructuring in HHS, CMS and CMMI to improve responsiveness and consistency across federal agencies and programs.

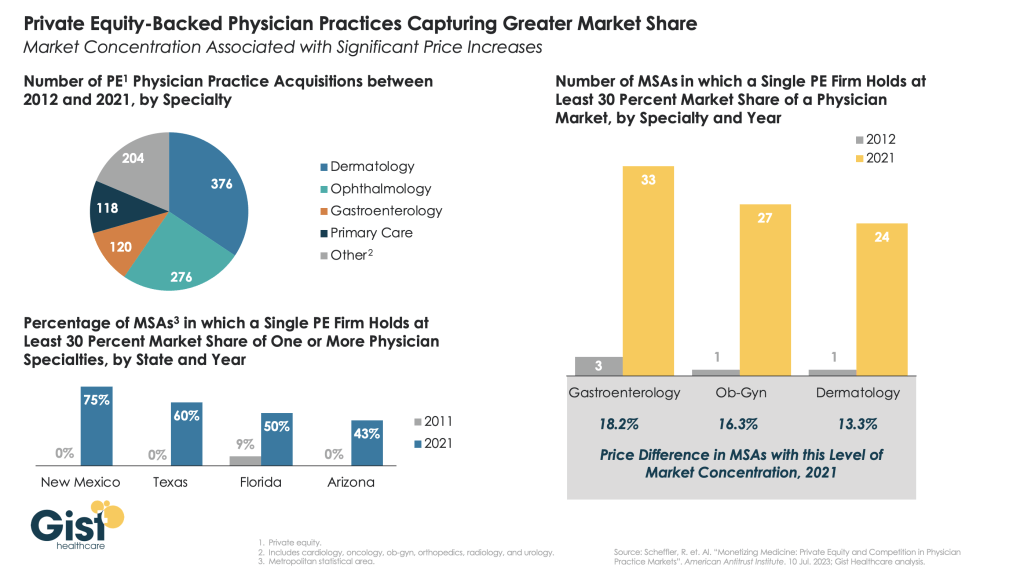

Sutton’s experience as the point for CMMI is significant. Like Adam Boehler, Brad Smith and other top Trump Healthcare 2.0 leaders, he brings prior experience in federal health agencies and operating insight from private equity-backed ventures (Honest Health, Privia, Evergreen Nephrology funded through Nashville-based Rubicon Founders). Sutton’s deals have focused on physician-driven risk-bearing arrangements with Medicare with funding from private investors.

The Trump Healthcare 2.0 team share a view that the healthcare system is unnecessarily expensive and wasteful, overly-regulated and under-performing. They see big hospitals and drug companies as complicit—more concerned about self-protection than consumer engagement and affordability.

They see flawed incentives as a root cause, and believe previous efforts by CMS and CMMI veered inappropriately toward DEI and equity rather than reducing health costs.

And they think physicians organized into risk bearing structures with shared incentives, point of care technologies and dependable data will reduce unnecessary utilization (spending) and improve care for patients (including access and affordability).

There’s will be a more aggressive approach to spending reduction and value-creation with Medicare as the focus: stronger alternative payment models and expansion of Medicare Advantage will book-end their collective efforts as Trump Healthcare 2.0 seeks cost-reduction in Medicare.

What’s ahead?

Trump Healthcare 2.0 value-based care is a take-no prisoners strategy in which private insurers in Medicare Advantage have a seat at their table alongside hospitals that sponsor ACOs and distribute the majority of shared savings to the practicing physicians. But the agenda will be set, and re-set by the administration and link-minded physician organizations like America’s Physician Groups and others that welcome financial risk-sharing with Medicare and beyond.

The results of the Trump Healthcare 2.0 value agenda will be unknown to voters in the November 2026 mid-term but apparent by the Presidential campaign in 2028. In the interim, surrogate measures for performance—like physician participation and projected savings–will be used to show progress and the administration will claim success. It will also spark criticism especially from providers who believe access to needed specialty care will be restricted, public and rural health advocates whose funding is threatened, teaching and clinical research organizations who facing DOGE cuts and regulatory uncertainty, patient’s right advocacy groups fearing lack of attention and private payers lacking scalable experience in Medicare Advantage and risk-based relationships with physicians.

Last week, the American Medical Association named Dr. John Whyte its next President replacing widely-respected 12-year CEO/EVP Jim Madara. When he assumes this office in July, he’ll inherit an association that has historically steered clear of major policy issues but the administration’s value-based care agenda will quickly require his attention.

Physicians including AMA members are restless:

At last fall’s House of Delegates (HOD), members passed a resolution calling for constraints on not-for-profit hospital’ tax exemptions due to misleading community benefits reporting and more consistency in charity care reporting by all hospitals.

The majority of practicing physicians are burned-out due to loss of clinical autonomy and income pressures—especially the 75% who are employees of hospitals and private-equity backed groups. And last week, the American College of Physicians went on record favoring “collective action” to remedy physician grievances. All impact the execution of the administration’s value-based agenda.

Arguably, the most important key to success for the Trump Healthcare 2.0 is its value agenda and physician support—especially the primary care physicians on whom the consumer engagement and appropriate utilization is based. It’s a tall order.

The Trump Healthcare 2.0 value agenda is focused on near-term spending reductions in Medicare. Savings in federal spending for Medicaid will come thru reconciliation efforts in Congress that will likely include work-requirements for enrollees, elimination of subsidies for low-income adults and drug formulary restrictions among others. And, at least for the time being, attention to those with private insurance will be on the back burner, though the administration favors insurance reforms adding flexible options for individuals and small groups.

The Trump Healthcare 2.0 value-agenda is disruptive, aggressive and opportunistic for physician organizations and their partners who embrace performance risk as a permanent replacement for fee for service healthcare. It’s a threat to those that don’t.