https://wendellpotter.substack.com/p/company-behind-namath-ads-has-long

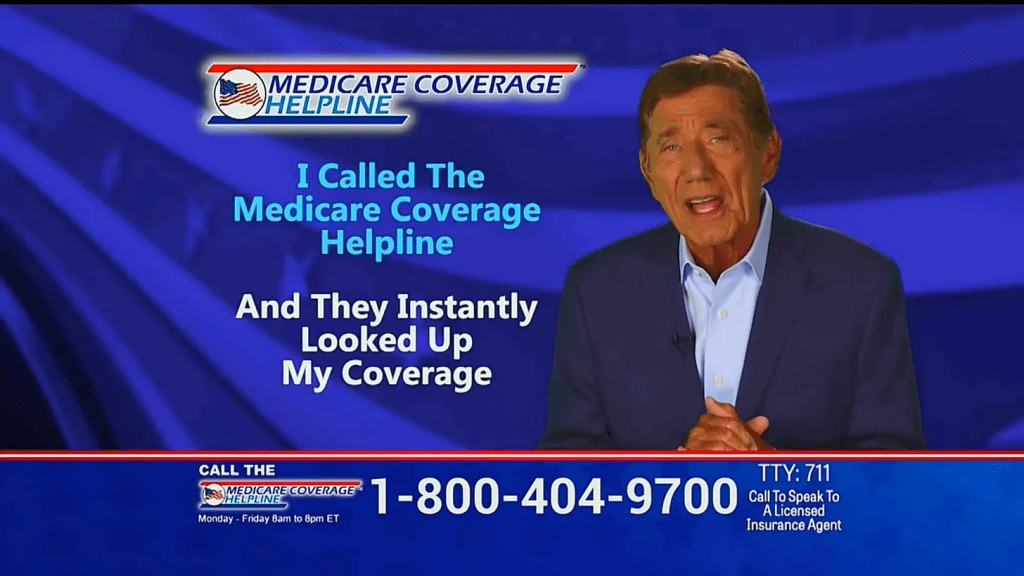

Former New York Jets superstar Joe Namath can be seen every year during Medicare open enrollment hocking plans that tell seniors how great their life would be if only they signed up for a Medicare Advantage plan. From October 15 to December 7 last year alone, Joe Namath ads ran 3,670 times, according to iSpot, which tracks TV advertising.

But the company behind those ads, now called Blue Lantern Health, and their products, HealthInsurance.com and the Medicare Coverage Helpline, have an expansive rap sheet of misconduct, including prosecutions by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission, and a recent bankruptcy filing that critics say is designed to jettison the substantial legal liabilities the firm has incurred. In September 2023, the company became Blue Lantern; before that, it was called Benefytt; and before that, Health Insurance Innovations. Forty-three state attorneys general had settled with the company in 2018, with it paying a $3.4 million fine. A close associate of the company, Steven Dorfman, has also been prosecuted by the FTC, in addition to the Department of Justice.

Namath himself has a bit of a checkered past when it comes to his business associates—in the early 1970s, he co-owned a bar frequented by members of the Colombo and Lucchese crime families, according to reporting at the time cited in a 2004 biography. Due to the controversy surrounding the bar, Namath was forced by the NFL Commissioner to sell his interest in it. Last year, it was revealed that Namath had employed a prolific pedophile coach at his football camp, also in the 1970s, and the 80-year-old ex-quarterback is now being sued by one of the coach’s victims.

The Namath ads are the main illustration of the behemoth Medicare Advantage marketing industry, which is designed to herd seniors into Medicare Advantage plans that restrict the doctors and hospitals that seniors can go to and the procedures they can access through the onerous “prior authorization” process, and it costs the federal government as much as $140 billion annually compared to traditional Medicare. Over half of seniors—nearly 31 million people—are now in Medicare Advantage, and there is little understanding of the drawbacks of the program. Seniors are aware that they may receive modest gym or food benefits but typically do not realize that they may be giving up their doctors, their specialists, their outpatient clinics, and their hospitals in favor of an in-network alternative that may be lower quality and farther away.

How so many seniors are lured into Medicare Advantage

Blue Lantern—with its powerful private equity owner Madison Dearborn—may be the key to understanding how so many people have been ushered into Medicare Advantage—and the pitfalls that private equity’s rapid entrance into health care can create for ordinary Americans.

While Blue Lantern is just one company, it is a Rosetta Stone for everything that is wrong with American health care today—fraud, profiteering, lawbreaking, no regard for patient care—where only the public comes out the loser.

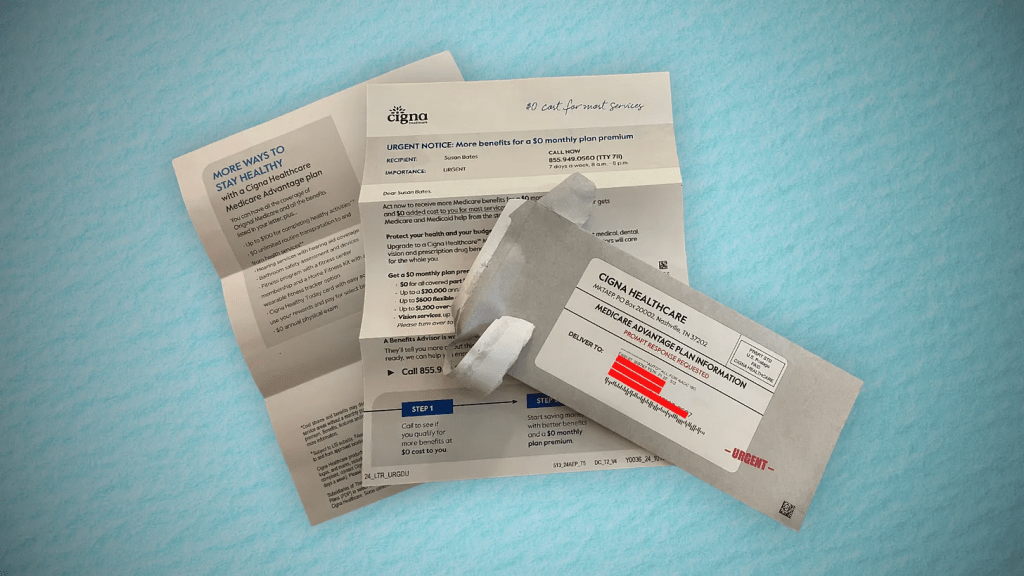

Blue Lantern uses TV ads and, at least until regulators began poking around, a widespread telemarketing operation, being one of the main firms charged with generating “leads” that are then sold to brokers and insurers, as Medicare Advantage plans are banned from cold-calling. Court filings reviewed by HEALTH CARE Un-Covered allege that after legal discovery, Blue Lantern (then known as Benefytt) at minimum dialed seniors over 17 million times, potentially in violation of federal law that requires telemarketers to properly identify themselves and who they are working for—ultimately, in this case, insurers that generate huge profits from Medicare Advantage.

The Namath ads have been running since 2018 when the company was named Health Insurance Innovations—the same year the FTC began prosecuting Simple Health Plans, along with its then-CEO Steven Dorfman. The Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel identified Health Insurance Innovations as a “successor” to Simple Health Plans. After five years of likely exceptionally costly litigation, for which Dorfman is represented by jet-set law firm DLA Piper, on February 9, the FTC won a $195 million judgment against Simple Health Plans and Dorfman. The FTC alleged in 2019 that Dorfman had lied to the court when he said that he did not control any offshore accounts. The FTC found $20 million, but the real number is probably higher.

Friends in high places

In February 2020, Trump’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, said that the Namath ads might not “look or sound like the future of health care,” but that they represented “real savings, real options” for older Americans.

In March 2020, Health Insurance Innovations (HII) changed its name to Benefytt, and in August 2020, it was acquired by Madison Dearborn Partners. Madison Dearborn has close ties to the Illinois Democratic elite, pumping over $916,000 into U.S. Ambassador to Japan Rahm Emanuel’s campaigns for Congress and mayor of Chicago.

In September 2021, HII settled a $27.5 million class action lawsuit. The 230,000 victims received an average payout of just $80.

In July 2022, the SEC charged HII/Benefytt and its then-CEO Gavin Southwell with making fraudulent representations to investors about the quality of the health plans it was marketing. “HII and Southwell…told investors in earnings calls and investor presentations that HII’s consumer satisfaction was 99.99 percent and state insurance regulators received very few consumer complaints regarding HII. In reality, HII tracked tens of thousands of dissatisfied consumers who complained that HII’s distributors made misrepresentations to sell the health insurance products, charged consumers for products they did not authorize and failed to cancel plans upon consumers’ requests,” the SEC found, with HII/Benefytt and Southwell ultimately paying a $12 million settlement in November 2022.

By August 2022, Benefytt had paid $100 million to settle allegations that it had fraudulently directed people into “sham” health care plans. “Benefytt pocketed millions selling sham insurance to seniors and other consumers looking for health coverage,” the FTC’s Director of Consumer Protection, Samuel Levine, said at the time.

Bankruptcy and another name change

In May 2023, Benefytt declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy—where the company seeks to continue to exist as a going concern, as opposed to Chapter 9, when the company is stripped apart for creditors—in the Southern District of Texas. The plan of bankruptcy was approved in August. The Southern Texas Bankruptcy Court has been mired in controversy in recent months as one of the two judges was revealed to be in a romantic relationship with a woman employed by a firm, Jackson Walker, that worked in concert with the major Chicago law firm Kirkland and Ellis to move bankruptcy cases to Southern Texas and monopolize them under a friendly court. While the other judge on the two-judge panel handled the Benefytt case, Jackson Walker and Kirkland and Ellis were retained by Benefytt, and the fees paid to Jackson Walker by Benefytt were delayed by the court as a result of the controversy.

In September 2023, Benefytt exited bankruptcy and became Blue Lantern.

The August approval of the bankruptcy plan was vocally opposed by a group of creditors who had sued Benefytt over violations of the Telephone Consumer Privacy Act (TCPA). The creditors asserted that Benefytt had substantial liabilities, with millions of calls made where Benefytt did not identify the ultimate seller—Medicare Advantage plans run by UnitedHealth, Humana, and other firms prohibited from directly contacting people they have no relationship with—and violations fined at $1,500 per willful violation.

Attorneys for those creditors stated in a filing reviewed by HEALTH CARE Un-Covered that Madison Dearborn always planned “to steer Benefytt into bankruptcy,” if they were unable to resolve the substantial liabilities they owed under the TCPA.

Madison Dearborn “knew that Benefytt’s TCPA liabilities exceeded its value, but purchased Benefytt anyway, for the purpose of trying to quickly extract as much money and value as they could before those liabilities became due,”

the August 25, 2023, filing stated on behalf of Wes Newman, Mary Bilek, George Moore, and Robert Hossfeld, all plaintiffs in proposed TCPA class action suits. The filing went on to say that the bankruptcy was inevitable “if—after siphoning off any benefit from the illegal telemarketing alleged herein—[Madison Dearborn] could not obtain favorable settlements or dismissals for the telemarketing-related lawsuits against Benefytt.”

Under the bankruptcy plan, Blue Lantern/Benefytt is released from the TCPA claims, but individuals harmed can affirmatively opt-out of the release, which is why the bankruptcy court justified its approval. Over 7 million people—the total numbers in Benefytt’s database, according to the plaintiffs—opting out of the third-party release is an enormous administrative hurdle for plaintiffs’ lawyers to pass, massively limiting the likelihood of success of any class-action litigation against Blue Lantern going forward.

Their attorney, Alex Burke, stated in court that “[t]his bankruptcy is an intentional and preplanned continuation of a fraud.” His statement was before 3,670 more Namath ads ran during 2023 open enrollment.

In response to requests for comment from HEALTH CARE un-covered, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services did not answer questions about Benefytt and why the company was simply not barred from the Medicare Advantage market altogether.

Corporations have used the bankruptcy process in recent years to free themselves from criminal and civil liability, with opioid marketer Purdue Pharma being the most prominent recent example. The Supreme Court is reviewing the legality of Purdue’s third-party releases currently, with a decision expected in late spring.

The role that private equity plays in keeping Benefytt going cannot be overstated.

Without Madison Dearborn or another private equity firm eager to take on such a risky business with such a long history of legal imbroglios, it is almost certain that Benefytt would no longer exist—and the Joe Namath ads would disappear from our televisions. Instead, Madison Dearborn keeps them going, suckering seniors into Medicare Advantage plans.

This is part and parcel of the ongoing colonization by private equity into America’s health care system. Private equity is making a major play into Medicare Advantage.

It has pumped billions of dollars into purchasing hospitals. It has invested in hospice care. It is gobbling up doctors’ groups. It is acquiring ambulance companies. It is hoovering up nurse staffing firms. It is making huge investments into health tech. It is in nursing homes. And it is in health insurance. Nothing about America’s health care system is untouched by private equity.

That’s a problem, experts say.

“I’ve been screaming at the TV every time Joe Namath gets on—it is not an official Medicare website,” said Laura Katz Olson, a professor of political science at Lehigh University who has written on private equity’s role in the health care system.

“Private equity has so much money to deploy, which is far more than they have opportunities to buy. As such, they are desperately looking for opportunities to invest. There’s a lot of money in Medicare Advantage—it’s guaranteed money from the federal government, which makes it perfect for the private equity playbook.”

Eileen Appelbaum, the co-director at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, who has also studied private equity’s role in health care, concurred that private equity was a perfect fit for Medicare marketing organizations.

“I think basically the whole privatized Medicare situation is ready for all kinds of exploitation and misrepresentations and denying people the coverage that they need,” she said. “My email is inundated with these totally misleading ads. Private equity took a look at this and said, “look at that, it’s possible to do something that’s misleading and make a lot of money.”

Madison Dearborn receives a large portion of its capital from public pension funds like the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) and the Washington State Investment Fund—people who are dependent on Medicare. Appelbaum said that the pension funds exercise little oversight over their investments in private equity. “Pension funds may have the name of the company that they are invested in, they’re told that it’s ‘part of our health care investment portfolio,’ but they don’t find out what they really do until there’s a scandal.

It is amazing that pension funds give so much money to private equity with so little information about how their money is being spent.”