Category Archives: Public Discourse

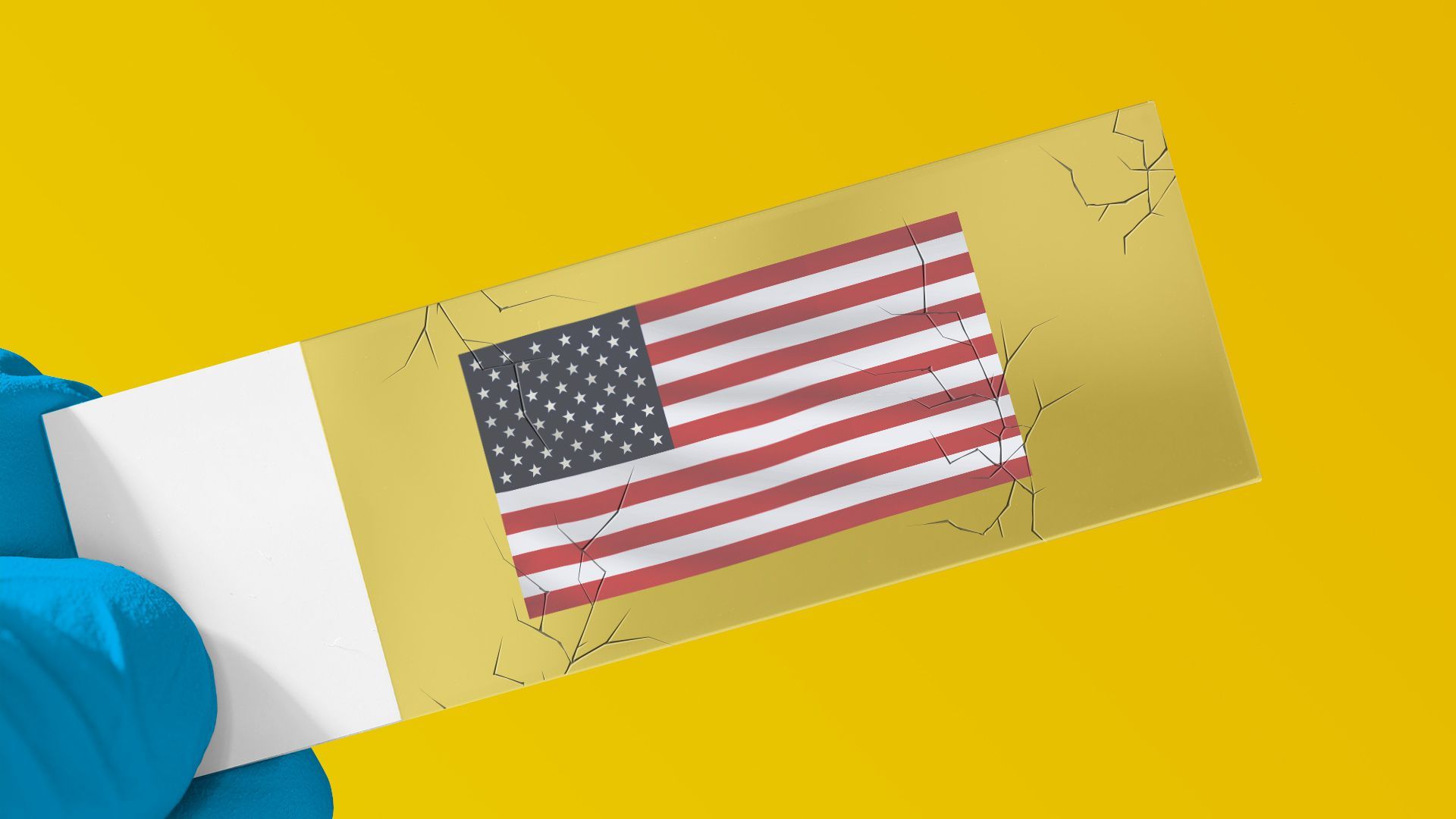

The norms around science and politics are cracking

https://www.axios.com/science-politics-norms-cracking-f67bcff2-b399-44f4-8827-085573f5ae52.html

Crafting successful public health measures depends on the ability of top scientists to gather data and report their findings unrestricted to policymakers.

State of play: But concern has spiked among health experts and physicians over what they see as an assault on key science protections, particularly during a raging pandemic. And a move last week by President Trump, via an executive order, is triggering even more worries.

What’s happening: If implemented, the order creates a “Schedule F” class of federal employees who are policymakers from certain agencies who would no longer have protection against being easily fired— and would likely include some veteran civil service scientists who offer key guidance to Congress and the White House.

- Those agencies might handle the order differently, and it is unclear how many positions could fall under Schedule F — but some say possibly thousands.

- “This much-needed reform will increase accountability in essential policymaking positions within the government,” OMB director Russ Vought tells Axios in a statement.

What they’re saying: Several medical associations, including the Infectious Diseases Society of America, strongly condemned the action, and Democrats on the House oversight panel demanded the administration “immediately cease” implementation.

- “If you take how it’s written at face value, it has the potential to turn every government employee into a political appointee, who can be hired and fired at the whim of a political appointee or even the president,” says University of Colorado Boulder’s Roger Pielke Jr.

- Protections for members of civil service allow them to argue for evidence-based decision-making and enable them to provide the best advice, says CRDF Global’s Julie Fischer, adding that “federal decision-makers really need access to that expertise — quickly and ideally in house.”

Between the lines: Politics plays some role in science, via funding, policymaking and national security issues.

- The public health system is a mix of agency leaders who are political appointees, like HHS Secretary Alex Azar, and career civil servants not dependent on the president’s approval, like NIAID director Anthony Fauci.

- “Public health is inherently political because it has to do with controlling the way human beings move around,” says University of Pennsylvania’s Jonathan Moreno.

Yes, but: The norm is to have a robust discussion — and what has been happening under the Trump administration is not the norm, some say.

- “Schedule F is just remarkable,” Pielke says. “It’s not like political appointees editing a report, [who are] working within the system to kind of subvert the system. This is an effort to completely redefine the system.”

- The Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Stephen Morrison says that the administration has been defying normative practices, including statements denigrating scientists, the CDC and FDA.

The big picture: Public trust in scientists,which tends to be high, is taking a hit, not only due to messaging from the administration but also from public confusion over changes in guidance, which vacillated over masks and other suggestions.

- Public health institutions “need to have the trust of the American people. In order to have the trust of the American people, they can’t have their autonomy and their credibility compromised, and they have to have a voice,” Morrison says.

- “If you deny CDC the ability to have briefings for the public, and you take away control over authoring their guidance, and you attack them and discredit them so public perceptions of them are negative, you are taking them out of the game and leaving the stage completely open for falsehoods,” he adds.

- “All scientists don’t agree on all the evidence, every time. But what we do agree on is that there’s a process. We look at what we know, we decide what we can clearly recommend based on what we know, sometimes when we learn more, we change our recommendations, and that’s the scientific process,” Fischer says.

What’s next: The scientific community is going to need to be proactive on rebuilding public trust in how the scientific process works and being clear when guidance changes and why it has changed, Fischer says.

Cartoon – Where Liberty Ends

Healthcare groups call racism a ‘public health’ concern in wake of tensions over police brutality

After days of protests across the world against police brutality toward minorities sparked by the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, healthcare groups are speaking out against the impact of “systemic racism” on public health.

“These ongoing protests give voice to deep-seated frustration and hurt and the very real need for systemic change. The killings of George Floyd last week, and Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor earlier this year, among others, are tragic reminders to all Americans of the inequities in our nation,” Rick Pollack, president and CEO of the American Hospital Association (AHA), said in a statement.

“As places of healing, hospitals have an important role to play in the wellbeing of their communities. As we’ve seen in the pandemic, communities of color have been disproportionately affected, both in infection rates and economic impact,” Pollack said. “The AHA’s vision is of a society of healthy communities, where all individuals reach their highest potential for health … to achieve that vision, we must address racial, ethnic and cultural inequities, including those in health care, that are everyday realities for far too many individuals. While progress has been made, we have so much more work to do.”

The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) also decried the public health inequality highlighted by the dual crises.

“The violent interactions between law enforcement officers and the public, particularly people of color, combined with the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on these same communities, puts in perspective the overall public health consequences of these actions and overall health inequity in the U.S.,” SHEA said in a statement. Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) executives called for health organizations to do more to address inequities.

“Over the past three months, the coronavirus pandemic has laid bare the racial health inequities harming our black communities, exposing the structures, systems, and policies that create social and economic conditions that lead to health disparities, poor health outcomes, and lower life expectancy,” said David Skorton, M.D., AAMC president and CEO, and David Acosta, M.D., AAMC chief diversity and inclusion officer, in a statement.

“Now, the brutal and shocking deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery have shaken our nation to its core and once again tragically demonstrated the everyday danger of being black in America,” they said. “Police brutality is a striking demonstration of the legacy racism has had in our society over decades.”

They called on health system leaders, faculty researchers and other healthcare staff to take a stronger role in speaking out against forms of racism, discrimination and bias. They also called for health leaders to educate themselves, partner with local agencies to dismantle structural racism and employ anti-racist training.

U.S. Passes 2 Million Coronavirus Cases as States Lift Restrictions, Raising Fears of a Second Wave

The number of confirmed U.S. coronavirus cases has officially topped 2 million as states continue to ease stay-at-home orders and reopen their economies and more than a dozen see a surge in new infections. “I worry that what we’ve seen so far is an undercount and what we’re seeing now is really just the beginning of another wave of infections spreading across the country,” says Dr. Craig Spencer, director of global health in emergency medicine at Columbia University Medical Center.

AMY GOODMAN: I certainly look forward to the day you’re sitting here in the studio right next to me, but right now the numbers are grim. The number of confirmed U.S. coronavirus cases has officially topped 2 million in the United States, the highest number in the world by far, but public health officials say the true number of infections is certain to be many times greater. Officially, the U.S. death toll is nearing 113,000, but that number is expected to be way higher, as well.

This comes as President Trump has announced plans to hold campaign rallies in several states that are battling new surges of infections, including Florida, Texas, North Carolina and Arizona — which saw cases rise from nearly 200 a day last month to more than 1,400 a day this week.

On Tuesday, the country’s top infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, called the coronavirus his worst nightmare.

DR. ANTHONY FAUCI: Now we have something that indeed turned out to be my worst nightmare: something that’s highly transmissible, and in a period — if you just think about it — in a period of four months, it has devastated the world. … And it isn’t over yet.

AMY GOODMAN: This comes as Vice President Mike Pence tweeted — then deleted — a photo of himself on Wednesday greeting scores of Trump 2020 campaign staffers, all of whom were packed tightly together, indoors, wearing no masks, in contravention of CDC guidelines to stop the spread of the coronavirus.

Well, for more, we’re going directly to Dr. Craig Spencer, director of global health in emergency medicine at Columbia University Medical Center. His recent piece in The Washington Post is headlined “The strange new quiet in New York emergency rooms.”

Dr. Spencer, welcome back to Democracy Now! It’s great to have you with this, though this day is a very painful one. Cases in the United States have just topped 2 million, though that number is expected to be far higher, with the number of deaths at well over 113,000, we believe, Harvard University predicting that that number could almost double by the end of September. Dr. Craig Spencer, your thoughts on the reopening of this country and what these numbers mean?

DR. CRAIG SPENCER: That’s a really good question. So, when you think about those numbers, remember that very early on, in March, in April, when I was seeing this huge surge in New York City emergency departments, we weren’t testing. We were testing people that were only being admitted to the hospital, so we were knowingly sending home, all across the epicenter, people that were undoubtedly infected with coronavirus, that are not included in that case total. So you’re right: The likely number is much, much higher, maybe 5, 10 times higher than that.

In addition, we know that that’s true for the death count, as well. This has become this political flashpoint, talking about how many people have died. We know that it’s an incredible and incalculable toll, over 100,000. Within the next few days, we’ll have more people that have died from COVID than died during World War I here in the United States. So that’s absolutely incredible.

We know that, also, just because New York City was bad, other places across the country might not get as bad, but that doesn’t mean that they’re not bad. So, we had this huge surge, of a bunch of deaths in New York City, you know, over 200,000 cases, tens of thousands of deaths. What we’re seeing now is we’re seeing this virus continue to roll across this country, causing these localized outbreaks.

And this is, I think, going to be our reality, until we take this serious, until we actually take the actions necessary to stop this virus from spreading. Opening up, like we’ve seen in Arizona and many other places, is exactly counter to what we need to be doing to keep this virus under control. So, yeah, I worry that what we’ve seen so far is an undercount and what we’re seeing now is really just the beginning of another wave of infections spreading across the country.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, Dr. Spencer, I want to ask — it’s not just in the U.S. that cases have hit this dreadful milestone. Worldwide, cases have now topped 7 million, although, like the U.S., the number is likely to be much higher because of inadequate testing all over the world. But I’d like to focus on the racial dimension of the impact of coronavirus, not just in the U.S., but also worldwide. Just as one example, in Brazil — and this is a really stunning statistic — that in Rio’s favelas, more people have died than in 15 states in Brazil combined. So, could you talk about this, both in the context of the U.S., and explain whether that is still the case, and what you expect in terms of this racial differential, how it will play out as this virus spreads?

DR. CRAIG SPENCER: Absolutely. What we’re seeing, not just in the United States, but all over the world, is coronavirus is amplifying these racial and ethnic inequities. It is impacting disproportionately vulnerable and already marginalized populations.

Starting here in the U.S., if you think about the fact, in New York City, the likelihood of dying from coronavirus was double if you’re Black or African American or Latino or Hispanic, double than what it was for white or Asian New Yorkers, so we already know that this disproportionate impact on already marginalized and vulnerable communities exists here in the United States, in the financial capital of the world. It’s the same throughout the U.S. A lot of the data that we’re seeing over the past few days, as we’re getting this disaggregated data by race and ethnic background, is that it is hitting these communities much harder than it is hitting white and other communities in the United States.

The statistics that you give for Brazil are being played out all over the world. We know that communities that already lack access to good healthcare or don’t have the same economic ability to stay home and participate in social distancing are being disproportionately impacted.

That is why we need to focus on and think about, in our public health messaging and in our public health efforts, to think about those communities that are already on the margins, that are already vulnerable, that are already suffering from chronic health conditions that may make them more likely to get infected with and die from this disease. We need to think about that as part of our response, not just in New York, not just in the U.S., but in Brazil, in Peru, in Ecuador, in South Africa, in many other countries, where we’re seeing the disproportionate number of cases coming from now.

We’re seeing — you know, I think it was just pointed out that three-quarters of all the new cases, the record-high cases, over 136,000 this past weekend on one day, three-quarters of those are coming from just 10 countries. And we know that that will continue, and it will burn through those countries and will continue through many more.

As of right now, we haven’t seen huge numbers in places like West Africa and East Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, where many people were concerned about initially. Part of that is because they have in place a lot of the tools from previous outbreaks, especially in West Africa around Ebola. But it may be that we need more testing. It may be that we’re still waiting to see the big increase in cases that may eventually hit there, as well.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Dr. Spencer, you mentioned that on Sunday — it was Sunday where there were 136,000 new infections, which was a first. It was the highest number since the virus began. But even as the virus is spreading, much like states opening in the U.S., countries are also starting to reopen around the world, including countries that have now among the highest outbreaks. Brazil is now second only to the U.S. in the number of infections, and Russia is third, and these countries are opening, along with India and so on. So, could you — I mean, there are various reasons that countries are opening. A lot of them are not able — large numbers of people are not able to survive as long as the country is closed, like, in fact, Brazil and India. So what are the steps that countries can take to reopen safely? What is necessary to arrest the spread of the virus and allow people at the same time to be out?

DR. CRAIG SPENCER: It’s tough, because we know that this virus cannot infect you if this virus does not find you. If there’s going to be people in close proximity, whether it’s in India or Illinois, this virus will pass and will infect you. I have a lot of concern, much as you pointed out, places like India, 1.3 billion people, where they’re starting to open up after a longer period of being locked down, and case numbers are steadily increasing.

You’re right that a lot of people around the world don’t have access to multitrillion-dollar stimulus plans like we do in the United States, the ability to provide at least some sustenance during this time that people are being forced at home. Many people, if they don’t go outside, don’t eat. If they don’t work, you know, their families can’t pay rent or really just can’t live.

What do we do? We rely on the exact same tools that we should be relying on here, which is good public health principles. You need to be able to locate those people who are sick, isolate them, remove them from the community, and try to do contact tracing to see who they potentially have exposed. Otherwise, we’re going to continue to have people circulating with this virus that can continue to infect other people.

It’s much harder in places where people may not have access to a phone or may not have an address or may not have the same infrastructure that we have here in the United States. But it’s absolutely possible. We’ve done this with smallpox eradication decades ago. We need to be doing this good, simple, bread-and-butter, basic public health work all around the world. But that takes a lot of commitment, it takes a lot of money, and it takes a lot of time.

AMY GOODMAN: It looks like President Trump is reading the rules and just doing the opposite — I mean, everything from pulling out of the World Health Organization, which — and if you could talk about the significance of this? You’re a world health expert. You yourself survived Ebola after working in Africa around that disease. And also here at home, I mean, pulling out of Charlotte, the Republican convention, because the governor wouldn’t agree to no social distancing, and he didn’t want those that came to the convention to wear masks. If you can talk about the significance, what might seem trite to some people, but what exactly masks do? And also, in this country, the states we see that have relaxed so much — he might move, announce tomorrow, the convention to Florida. There’s surges there. There’s surges in Arizona, extremely desperate question of whether a lockdown will be reimposed there. What has to happen? What exactly, when we say testing, should be available? And do you have enough masks even where you work?

DR. CRAIG SPENCER: Great. Yes. So, let me answer each of those. I think, first, on the World Health Organization, and really the rhetoric that is coming from the White House, it needs to be one of global solidarity right now. We are not going to beat this alone. I think that that’s been proven. This idea of American exceptionalism now is only true in that we have the most cases of anywhere in the world. We are not going to beat this alone. No country is going to beat this alone. As Dr. Fauci said, this is his worst nightmare. It’s my worst nightmare, as well. This is a virus that was first discovered just months ago, and has now really taken over the world. We need organizations like the World Health Organization, even if it isn’t perfect. And I’ve had qualms with it in the past. I’ve written about it, I’ve spoken about it, about the response as part of the West Africa Ebola outbreak that I witnessed firsthand. But at the end of the day, they do really, really good work, and they do the work that other organizations, including the United States, are not doing around the world, and that protects us. So, we absolutely, despite their imperfections, need to further invest and support them.

In terms of masks, masks may be, in addition to social distancing, one of the few things that really, really helps us and has proven to decrease transmission. We know that if a significant proportion of society — you know, 60, 70, 80% of people — are wearing masks, that will significantly decrease the amount of transmission and can prevent this virus from spreading very rapidly. Everyone should be wearing masks. I think, in the United States right now, we should consider the whole country as a hot zone. And the risk of transmission being very high, regardless of whether you’re in New York or North Dakota, people should be wearing a mask when they’re going outside and when they’re interacting with others that they generally don’t interact with.

We know the science is good. I will say that from a public health perspective, there was some initial reluctance and, really, I guess, some confusion early on about whether people should be using masks. We didn’t have a lot of the science to know whether it would help. We do now. And thankfully, we’re changing our recommendations.

We also were concerned about the availability of masks early on. As you mentioned, there was questions around availability of personal protective equipment, whether we had enough in hospitals to provide care while keeping providers safe. It’s better now, but there are still a lot of people who are saying that they’re reusing masks, that we still need more personal protective equipment. So, for the moment, everyone should be wearing a mask.

AMY GOODMAN: And for the protests outside?

DR. CRAIG SPENCER: Absolutely. Yeah, of course. Just because I think we have personal passions around public health crises, that doesn’t prevent us from being infected. From a public health perspective, of course I have concerns that people who are close and are yelling and are being tear-gassed and are not wearing masks, if that’s all the case, it’s certainly an environment where the coronavirus could spread.

So, what I’ve been telling everyone that’s protesting is exercise your right to protest — I think that’s great — but be safe. We are in a pandemic. We’re in a public health emergency. Wear a mask. Socially distance as much as you possibly can. Wash your hands.

AMY GOODMAN: And are you telling the authorities to stop tear-gassing and pepper-spraying the protesters?

DR. CRAIG SPENCER: I mean, well, one, it’s illegal. You should definitely stop tear-gassing. We know that what happens when people get tear-gassed is they cough, and it increases the secretions, which increases the risk. It increases the transmissibility of this virus.

In addition to that, you know, holding people and arresting them and putting them into small cells with others without masks is also, as we’ve seen from this huge number of cases in places like meatpacking plants or in jails, in prisons, the number of cases have been extremely high in those places. Putting people into holding cells for a prolonged period of time is not going to help; it’s definitely going to increase the transmissibility of this virus.

So, yes, everyone should be wearing a mask. I think everyone should have a mask on when you’re anywhere that your interacting with others can potentially spread this.

I think your other question was around testing. We know that right now testing has significantly increased in the U.S. Is it adequate? No, I don’t think so. I know I hear from a lot of people who say they still have to drive two to three hours to get a test. We still have questions around the reliability of some of serology tests, or the antibody tests. Those are the tests that will tell you whether or not you’ve been previously exposed and now have antibodies to the disease. Some of the more readily available tests just aren’t that great. And so, we can’t use them yet to make really widespread decisions on who might have antibodies, who might have protection and who can maybe more safely go back into society without the fear of being infected.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Dr. Spencer, we just have 30 seconds. Very quickly, there are 135 vaccines in development. What’s your prognosis? When will there be a vaccine or a drug treatment?

DR. CRAIG SPENCER: We have one drug that shortens the time that people are sick. We don’t know about the impact on mortality. There are other treatments that are in process now. Hopefully some of them work.

In terms of vaccines, we will have a vaccine, very likely, that we know is effective, probably at some time later this year. The bigger process is going to be how do we scale it up to make hundreds of millions of doses; how do we do it in a way that we can get it to all of the people that deserve it, not just the people that can pay for it. I think these are going to be some of the bigger questions and bigger problems that we’re going to face, going forward. But I’m optimistic that we’ll have a vaccine or many vaccines, hopefully, in the next year.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Craig Spencer, we want to thank you so much for being with us, director of global health in emergency medicine at Columbia University Medical Center. And thank you so much for your work as an essential worker. Dr. Spencer’s recent piece, we’ll link to at democracynow.org. It’s in The Washington Post, headlined “The strange new quiet in New York emergency rooms.”

When we come back, George Floyd’s brother testifies before Congress, a day after he laid his brother to rest. Stay with us.

Scientists caught between pandemic and protests

When protests broke out against the coronavirus lockdown, many public health experts were quick to warn about spreading the virus. When protests broke out after George Floyd’s death, some of the same experts embraced the protests. That’s led to charges of double standards among scientists.

Why it matters: Scientists who are seen as changing recommendations based on political and social priorities, however important, risk losing public trust. That could cause people to disregard their advice should the pandemic require stricter lockdown policies.

What’s happening: Many public health experts came out against public gatherings of almost any sort this spring — including protests over lockdown policies and large religious gatherings.

- But some of the same experts are supporting the Black Lives Matter protests, arguing that addressing racial inequality is key to tackling the coronavirus epidemic.

- The systemic racism that protesters are decrying contributes to massive health disparities that can be seen in this pandemic — black Americans comprise 13% of the U.S. population, but make up around a quarter of deaths from COVID-19. Floyd himself survived COVID-19 before he was killed by a now former police officer in Minneapolis.

- “While everyone is concerned about the risk of COVID, there are risks with just being black in this country that almost outweigh that sometimes,” Abby Hussein, an infectious disease fellow at the University of Washington, told CNN last week.

Yes, but: Spending time in a large group, even outdoors and wearing masks — as many of the protesters are — does raise the risk of coronavirus transmission, says Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota.

- In a Twitter thread over the weekend, coronavirus expert Trevor Bedford estimated that each day of protests would result in some 3,000 additional infections, which over time could lead to hundreds of additional deaths each day.

- Public health experts who work in the government have struck a cautionary note. Mass, in-person protests are a “perfect setup” for transmission of the virus, Anthony Fauci told radio station WTOP last week. “It’s a delicate balance because the reasons for demonstrating are valid, but the demonstration puts one at additional risk.”

The difference in tone between how some public health experts are viewing the current protests and earlier ones focused on the lockdowns themselves was seized upon by a number of critics, as well as the Trump campaign.

- “It will deepen the idea that the intellectual classes are picking winners and losers among political causes,” says Tom Nichols, author of the “The Death of Expertise.”

- Politico reported that the Trump campaign plans to restart campaign rallies in the next two weeks, with advisers arguing that “recent massive protests in metropolitan areas will make it harder for liberals to criticize him” despite the ongoing pandemic.

The current debate underscores a larger question: What role should scientists play in policymaking?

- “We should never try to harness the credibility of public health on behalf of our judgments as citizens,” writes Peter Sandman, a retired professor of environmental journalism. He tells Axios some scientists who supported one protest versus others “clearly damaged the credibility of public health as a scientific enterprise that struggles to be politically neutral.“

- But some are pushing back against the very idea of scientific neutrality. “Science is part of how we got to our racist system in the first place,” Susan Matthews wrote in Slate.

- Medical science has often betrayed the trust of black Americans, who receive less, and often worse, care than white Americans. That means — as Uché Blackstock, a physician and CEO of Advancing Health Equity, told NPR — that the pandemic presents “a crisis within a crisis.”

The big picture: The debate risks exacerbating a partisan divide among Americans in their reported trust in scientists.

- 53% of Democrats polled in late April — about a month before Floyd’s death — reported a “great deal of confidence in medical scientists to act in the public interests” versus 31% of Republicans.

- If science-driven policymaking continues to be seen as biased, it will have repercussions for public trust in issues beyond the pandemic, including climate change, AI and genetic engineering.

What to watch: If there is a rise in new cases in the coming weeks, there will be pressure to trace them — to protests, rallies and the reopening of states. How experts weigh in could affect how their recommendations will be viewed in the future — and whether the public, whatever their political leanings, will follow them again.

Cartoon – I’d Love to give them my Two Cents’ Worth

Protests essential despite risk of coronavirus spread, healthcare workers say

Though the protests that erupted after a black man died in police custody might result in spikes of COVID-19, some healthcare workers say that they are important, as racial disparities in healthcare is also a public health issue, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Public health experts and healthcare workers across the country are joining in the protests that began after George Floyd died at the hand of police in Minneapolis in late May. He is the most recent example of police brutality against black people and joins a long list of deaths of African Americans in police custody.

Healthcare experts and workers are saying though the protests may result in a new wave of coronavirus cases, the issue at hand is more important and the potential benefits outweigh the risks, especially since the risk of transmission is lower outside than inside when precautions are taken.

Darrell Gray, MD, a black gastroenterologist at the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, has been attending protests, telling the Journal, “I prioritize being at protests and peaceful demonstrations because I strongly believe that they can be leveraged to produce change.” He said that he is taking precautions, wearing a face mask and distancing himself as much as possible.

Dr. Gray also said that the pandemic has disproportionately affected black communities, as the underlying conditions that are linked to more severe COVID-19 illness, such as diabetes and high blood pressure, are more rampant in those communities.

Jennifer Nuzzo, DrPH, an epidemiologist and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security in Baltimore, also supports the protests, though she has not been able to attend one in person as yet due to time constraints.

She told the Journal although she is worried about virus transmission, “there are some categories of risk that are, for me, completely worth it.” These protests are in those categories, she said.

Dr. Nuzzo and other health experts have also said protesters can reduce the risk of transmission by wearing masks, trying to maintain 6 feet of social distance when possible and making sure they are washing their hands often or using hand sanitizer.

More than 1,000 public health and infectious disease experts and community stakeholders signed an open letter last week saying that demonstrations were important for combating race-based health inequities, largely a result of racism, the Journal reports.

Cartoon – Pillars of Democracy