The need for a coordinated national research strategy

Confused about the risks of dying from the coronavirus or of catching it from someone who seems healthy? We all are, and the dizzying differences in scientific opinion are now linked to political perspectives. Progressives cite evidence that loosening restrictions would cost lives and offer little benefit to the economy, while conservatives embrace evidence that the risks are low. We offer a guide to help navigate the tangle of numbers and suggest a way forward.

Google and many others display the number of cases and deaths (3.6 million and 138,840, respectively, by July 17). This invites a simple calculation for understanding the risk: divide the number who have died by the number who have been diagnosed. So, the chance of dying if infected is about 3.9%. Right? Well, not so fast. Six months into the pandemic, neither the number of deaths nor the number of people infected is known.

Some argue that deaths have been overemphasized since people who die of COVID are mostly older and sicker. Others suggest deaths have been overcounted since if a patient tests positive for COVID-19, it will likely be listed as the cause of death even if the person succumbs to another illness or, in some jurisdictions, dies due to an accident or suicide. Others argue that deaths have been undercounted.

Missing from the tally on any given day are those who died before testing was available, those who died shortly before or after but whose death has not yet been reported, or who died as an indirect result of the epidemic such as failing to seek medical care for fear of going to the hospital.

One carefully designed recent analysis compared deaths this year to the number of people who die during a “normal” year. The analysis concluded that through May, almost 100,000 people died from COVID-19 in addition to 30,000 who died from other causes related to the pandemic.

In short, uncertainty remains about the number of deaths due to COVID-19, which is supposed to be the easy part.

Estimating the number of people who have been infected is harder still. Most infected people are never formally diagnosed and never become one of the “cases” in the news. The limitations of the tests and the difficulty of attracting a representative population to be tested make it hard to estimate the true number of infections. The preferred test (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction-based tests) uses RNA technology to see if the virus is present in nasal or oral swabs. It is a good test, but still may miss infections in up to 30% of cases.

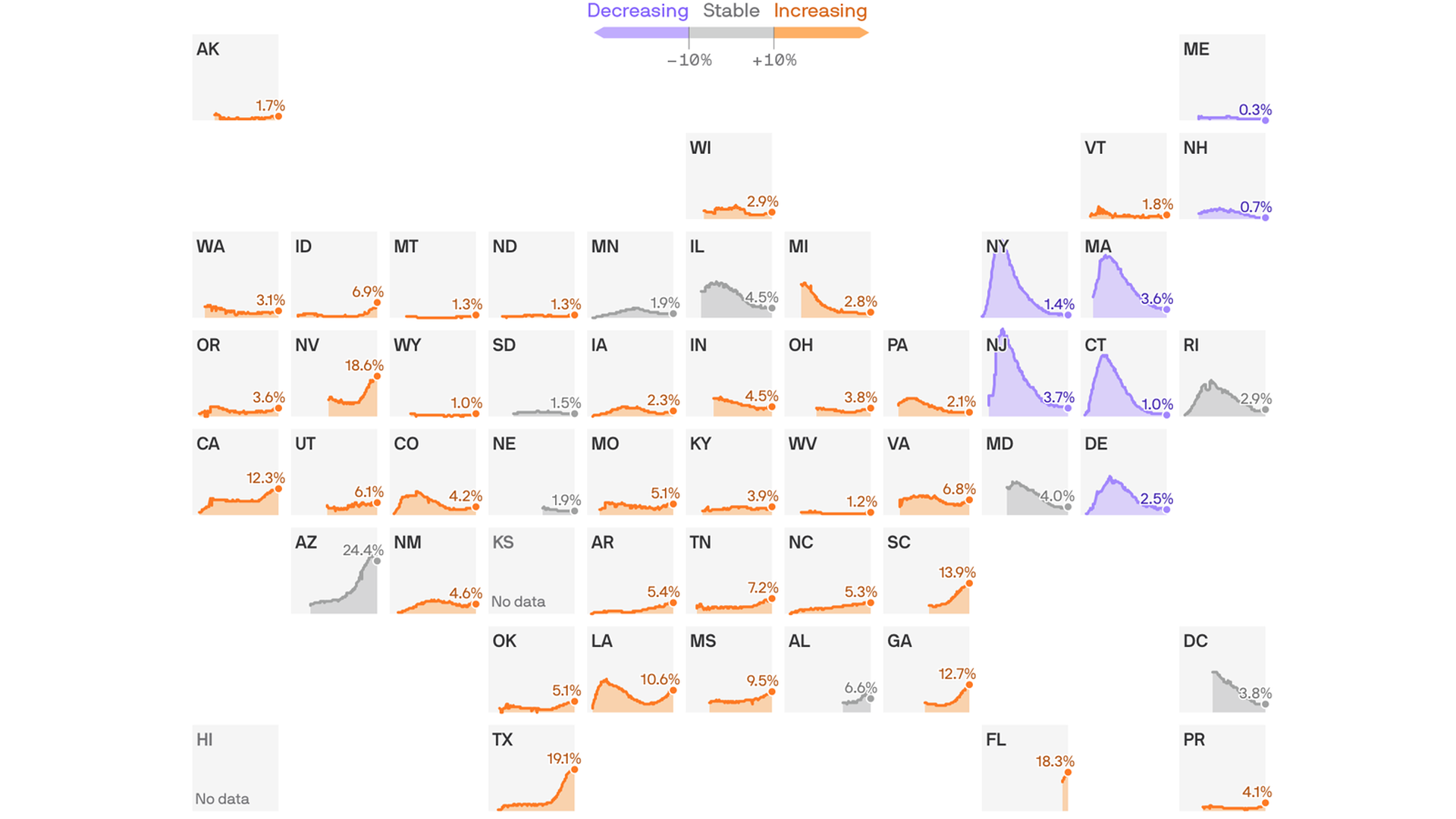

A second type of test uses blood samples to look for an antibody called immunoglobulin (Ig)G that implies the person was previously infected. Based on IgG test results, the CDC assumes that 5% to 8% of the population has been infected. That would mean 24 million Americans have already had COVID-19 or a very similar illness. That is more than 10 times the number of confirmed cases.

The number is consequential: a higher infection rate for the same number of deaths implies that the virus is less deadly. A review by a prominent epidemiologist considered 23 population studies with sample sizes of at least 500 people and found the percentage who have positive antibodies ranged from 0.1% to 48% — a 480-fold difference. Although the study was robustly criticized and at odds with highly cited, peer-reviewed research, it has appeared in over 30 news outlets, and the range of estimates allows people to pick a number that justifies their political position.

Contributing to this uncertainty is the FDA decision to, in a hurry to catch up for lost time, temporarily relax its standards for approving tests. Among over 300 antibody tests currently on the market, data on only a handful are publicly available, and some are being recalled.

The other number we need to know is how many people are spreading the infection without knowing it. Estimates are all over the place. Some major employers, including Stanford Healthcare, have systematically tested all of their employees and found very few infected people who do not have symptoms. In contrast, a CDC study of young, healthy adults working on an aircraft carrier found that 20% of those infected reported no symptoms.

So here we are, months into the epidemic without consensus on the basic information about how many people are infected, the risk of death for those infected, or the risk of asymptomatic transmission. In contrast to official agencies that use transparent methods to report the weather or the unemployment rate, trust in our official health statistics agencies has broken down as reports continue to emerge form myriad sources with conflicting methodologies and motivations.

The time has come to activate impartial groups, like the National Academy of Medicine, to build consensus on how to monitor the epidemic. We know the risks are serious. As cases have started to rise, whether or not the number of U.S. deaths is higher or lower than 130,000, the risk of inaction is too high.

We are staying near home, wearing masks, and treating COVID-19 as a serious threat to public health.