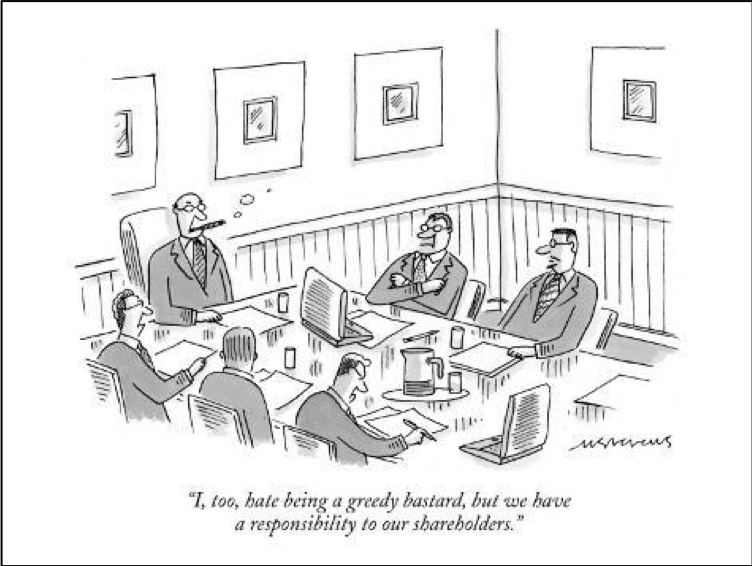

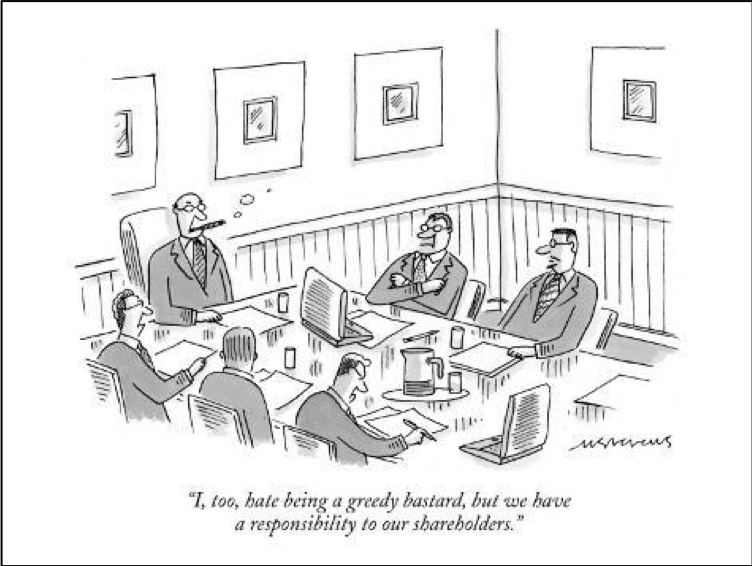

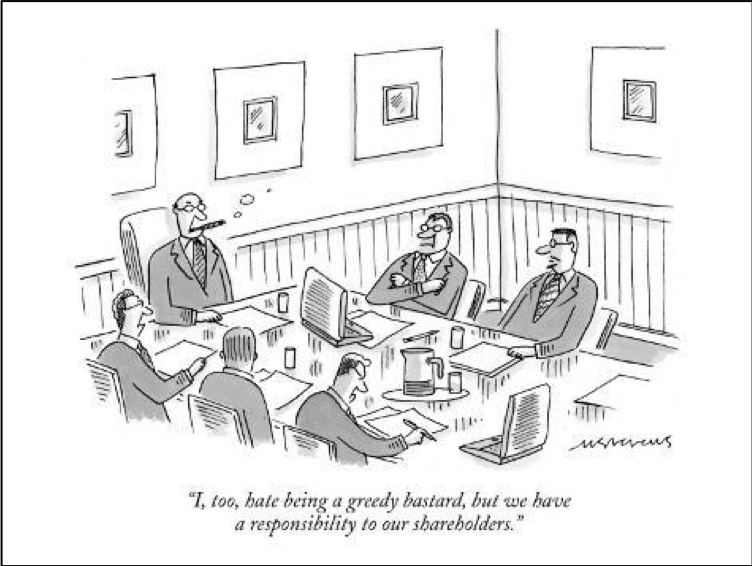

Cartoon – Modern Responsibility

President Trump on Monday moved to lift restrictions imposed on travelers to the U.S. from much of Europe and Brazil that were implemented last year to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, though the action is expected to be stopped by the incoming Biden administration.

Trump issued an executive order terminating the travel restrictions on the United Kingdom, Ireland, Brazil and the countries in Europe that compose the Schengen Area effective Jan. 26. The order came two days before Trump leaves office. President-elect Joe Biden’s team immediately signaled they would move to reverse the order.

“With the pandemic worsening, and more contagious variants emerging around the world, this is not the time to be lifting restrictions on international travel,” tweeted incoming White House press secretary Jen Psaki.

“On the advice of our medical team, the Administration does not intend to lift these restrictions on 1/26. In fact, we plan to strengthen public health measures around international travel in order to further mitigate the spread of COVID-19,” Psaki continued.

The order states that Trump’s action came at the recommendation of outgoing Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar. The memo cites the new order from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that requires passengers traveling by air to the U.S. to receive a negative COVID-19 test within three days before their flight departs, saying it will help prevent travelers from spreading the virus.

The Trump administration’s travel restrictions on China and Iran will remain in place, however, because, the order states, the countries “repeatedly have failed to cooperate with the United States public health authorities and to share timely, accurate information about the spread of the virus” and therefore cannot be trusted to implement the CDC’s order.

“Accordingly, the Secretary has advised me to remove the restrictions applicable to the Schengen Area, the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, and the Federative Republic of Brazil, while leaving in place the restrictions applicable to the People’s Republic of China and the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Trump’s order states. “I agree with the Secretary that this action is the best way to continue protecting Americans from COVID-19 while enabling travel to resume safely.”

Though Trump signed the order on Monday, the action does not take effect until six days after he leaves office and Biden is inaugurated.

The order comes as coronavirus cases and deaths continue to hit worrisome, record-high levels on a daily basis. Nearly 400,000 people in the U.S. and more than 2 million people globally have died from COVID-19. While two vaccines have been approved for emergency use in the U.S., the Trump administration has fallen far short of early targets in distributing and administering the vaccine.

The order will be one of the final actions that Trump takes with respect to the pandemic, after being widely criticized for regularly minimizing the threat posed by the virus.

Trump announced in mid-March of last year that he would impose travel restrictions on individuals entering the United States from the 26 countries that compose the Schengen Area, weeks after the first case was reported in the U.S. The move initially attracted scrutiny because it did not include the U.K. or Ireland, and the Trump administration later moved to restrict travel from those countries as well.

Trump later placed travel restrictions on Brazil at the end of May.

The executive order lifting the travel restrictions was one of several released by the White House on Monday as the final hours of Trump’s presidency wind down. Trump is also expected to grant a final slew of pardons before he leaves office on Wednesday.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/johndrake/2020/08/21/the-science-of-campus-outbreaks/#4c5704ae6893

On August 17, seven days after the start of in-person classes, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill announced that, due to a dramatic increase in Covid-19 on campus, all undergraduate classes would be held online for the remainder of the fall. Ithaca College and Michigan State pulled the plug on August 18. Two days later, N.C. State joined the club. More may follow. (The Chronicle of Higher Education maintains a live update feed.) In fact, only a minority of colleges and universities are still attempting fall instruction fully or primarily in person (about 25% at this writing).

Only time will tell if these rapid course changes were warranted and, of course, the answer may not be the same everywhere. Each institution is unique with respect to size, culture, infrastructure to provide online learning, and ability to cope with transmission.

In thinking about Covid-19 transmission on campus, it may be useful to know something about the science of epidemics among college students in general. There is a small scientific literature on disease outbreaks on campus. Campuses are special for several reasons. News photos of students lounging on green quads, engaged in late night study groups, or partying into the wee hours reminds us that if college is known for anything other than studying and college sports, it might be the unique gregariousness that attaches to what many people call the “college experience.”

Although outbreaks of infectious diseases on college campuses are routinely reported, there is little evidence that they are more explosive than in the general population. Outbreaks of directly transmitted diseases like measles, mumps, and whooping cough occur with some regularity and are typically contained through isolation and other public health measures. But, no study has been done to systematically examine how the campus environment differs from community-based transmission.

Influenza is a particularly interesting case because, like Covid-19, it is a respiratory disease transmitted directly through close contact and also has a short incubation period. The basic reproduction number (R0) is a measure of the explosiveness of an epidemic, with anything over R0 = 1 indicating the possibility of sustained transmission.

In 2014, CDC and academic scientists compiled a list of all estimates of R0 for influenza. While most estimates for the 2009 pandemic were between 1 and 2, estimates from some schools (not necessarily colleges or universities) were noticeably higher (2.3 for a school in Japan and 3.3 for a school in the United States), although other cases (Iran and the United Kingdom) were similar to the rest of the population.

Perhaps more importantly, a study in Pullman, Washington (home to Washington State University) estimated R0 of the 2009 pandemic flu to be around 6, which is two to four times larger than most other estimates. So there is some evidence that campus contagions may be more prone to outbreak than other places.

Since Covid-19 is typically much less severe in young adults than in older adults, another question that seems particularly important now is whether transmission among students remains primarily within the student population or readily spreads to the rest of the community.

In a measles outbreak at a university in China, the fraction of staff who were infected was not statistically different from the fraction of students. The total number of staff infected — three — was small, however, and it seems unlikely that this is the usual pattern.

A study of the 2009 influenza pandemic at the University of Delaware found that the risk of infection for people older than 30 was roughly half the risk of those that were 18 to 29.

An even more interesting aspect of the University of Delaware study is the association with student activities. Reports of influenza-like illness among students at a nearby emergency health center remained stable for almost a month after spring break. But cases increased almost five-fold following “Greek week”. In the final analysis, belonging to a fraternity or sorority doubled a student’s chances of being infected.

This is concerning now as cases of Covid-19 are rising among college students nationwide. College leaders such as Penn State president Eric Barron, University of Kansas chancellor Douglas Girod, and University of Tennessee chancellor Donde Plowman have reproached students, especially fraternities and sororities, for ignoring guidance to avoid large gatherings.

Yesterday, J. Michael Haynie, Vice Chancellor for Strategic Initiatives and Innovation publicly excoriated students at Syracuse University for “selfishly jeopardizing” the possibility of in-person instruction this fall. “Make no mistake,” he wrote, “there was not a single student who gathered on the Quad last night who did not know and understand that it was wrong to do so.”

The science of Covid-19 tells us that students are vulnerable, just like everyone else. Although the evidence is somewhat thin, what there is points only in one direction: because of their specific social structure, college campuses are especially prone to outbreaks of infectious diseases. As in the rest of society, the only way to slow down the Covid-19 pandemic on college campuses is to reduce the rate of infectious contacts. There is too much value in the college experience to reduce it to partying, and it should not be squandered altogether for the sake of the party experience.

Merkel says pandemic reveals limits of ‘fact-denying populism’

German Chancellor Angela Merkel told European Union (EU) countries Wednesday that the coronavirus pandemic is showing the limits of “fact-denying populism” as she urged the bloc to reach an agreement on an economic recovery package.

Merkel said that the EU “must show that a return to nationalism means not more, but less control,” according to France 24.

Without naming any specific nations, Merkel said: “We are seeing at the moment that the pandemic can’t be fought with lies and disinformation, and neither can it be with hatred and agitation.”

“Fact-denying populism is being shown its limits,” she added. “In a democracy, facts and transparency are needed. That distinguishes Europe, and Germany will stand up for it during its presidency.”

The pandemic has killed more than 100,000 people in the 27 EU nations and sparked what is expected to be the largest recession the continent has experienced in decades.

On Tuesday the EU released a report predicting the bloc’s economy will contract more than initially expected due to coronavirus-related lockdowns.

Merkel on Wednesday joined EU Economy Commissioner Paolo Gentiloni in urging the commission to quickly reach an agreement on the 750 billion-euro stimulus package proposed earlier this year.

“The depth of the economic decline demands that we hurry,” Merkel told lawmakers, according to The Associated Press. “We must waste no time — only the weakest would suffer from that. I very much hope that we can reach an agreement this summer. That will require a lot of readiness to compromise from all sides — and from you too.”