Iowa Democrats reported last night that their biggest priorities were beating President Trump and health care — but the meltdown of their election reporting systems left their presidential choices unresolved.

Why it matters: We’ve been writing for months that Democrats have a major choice ahead, either picking an advocate of Medicare for All — and siding with the plan that’s less popular with the rest of the country — or a public option advocate.

By the numbers: Several polls — including ones by NBC News, the National Exit Poll and AP Votecast — found that around four in 10 caucus voters said health care was their top issue.

Yes, but: Caucus-goers said they prefer a Democratic candidate who can beat Trump over one that agrees with them on issues, CNN reports.

The big picture: Republicans are more than happy to talk about Medicare for All — and its subsequent tax increases and expanded government role in health care — instead of protecting and building on the Affordable Care Act.

https://time.com/5759972/health-care-administrative-costs/

Whether it’s interpreting medical bills, struggling to get hospital records, or fighting with an insurance provider, Americans are accustomed to battling bureaucracy to access their health care. But patients’ time and effort are not the only price of this complexity. Administrative costs now make up about 34% of total health care expenditures in the United States—twice the percentage Canada spends, according to a new study published Monday in Annals of Internal Medicine.

These costs have increased over the last two decades, mostly due to the growth of private insurers’ overhead. The researchers examined 2017 costs and found that if the U.S. were to cut its administrative spending to match Canadian levels, the country could have saved more than $600 billion in just that one year.

“The difference [in administrative costs] between Canada and the U.S. is enough to not only cover all the uninsured but also to eliminate all the copayments and deductibles, and to amp up home care for the elderly and disabled,” says Dr. David Himmelstein, a professor at the CUNY School of Public Health at Hunter College and co-author of the study. “And frankly to have money left over.”

Research has long shown that the U.S., which uses a disparate system of private providers and insurers, has higher administrative costs than other developed countries that use single-payer systems. But the Annals study puts a finer point on it: as the first major effort to calculate administrative costs across the U.S. health system in nearly two decades, the researchers found that the gap between the U.S. and Canada has widened significantly.

The U.S. now spends nearly five times more per person on health care administration than Canada does. The U.S. administrative costs came out to $812 billion in 2017, or $2,497 per person in the U.S. compared with $551 per person in Canada, according to the Annals study.

Along with Himmelstein, co-authors Steffie Woolhandler and Terry Campbell examined administrative costs for insurance companies and government agencies that administer healthcare, as well as costs in four settings: hospitals, nursing homes, home care agencies and hospices and physician practices. For each category, the researchers determined which costs were administrative and conducted analyses to adjust comparisons between relative costs in the U.S. and Canada.

Insurers’ overhead, the largest category, totaled $275.4 billion in the U.S. in 2017, or 7.9% of all national health expenditures, compared with $5.36 billion in Canada, or 2.8% of national health expenditures. The American number included $45 billion in government spending to administer health care programs and $229.5 billion in private insurers’ overhead and profits, which covers employer plans and managed care plans funded by Medicare and Medicaid.

This insurance overhead accounted for most of the total increase in administrative spending in the U.S. since 1999, according to the study. While the share of Americans covered by commercial insurance plans has not changed much, private insurers have expanded their role as subcontractors handling what are known as “managed care” plans for Medicaid and Medicare. The study notes that most Medicaid recipients are now on private managed care plans and about one third of Medicare enrollees now have Medicare Advantage plans. Both of these types of plans have higher overhead costs than the publicly administered alternatives.

“We were struck, and frankly hadn’t expected it until we delved into the data, by the huge increase in insurance overhead,” Himmelstein told TIME.

Other reports, including one by the Center for American Progress published last April, have identified ways to reduce administrative costs without moving the U.S. to a single-payer health care system. But Himmelstein says his study shows that a public option that preserves private insurance wouldn’t provide the same savings as a traditional single-payer system. “We could streamline the bureaucracy to some extent with other approaches, but you can’t get nearly the magnitude of savings that we could get with a single payer,” Himmelstein says, adding, “If the Medicare public option includes the Medicare Advantage plans, it’s actually conceivable that the public option would increase the bureaucratic costs.”

Most of the public option plans proposed by Democratic presidential candidates are not detailed enough to determine exact costs, Himmelstein says. But overall, he believes they won’t result in significant cost savings.

In addition to their research, Himmelstein and Woolhandler have been longtime advocates for single-payer health care. They co-founded the group Physicians for a National Health Program, which advocates for a single-payer system. They also conducted the initial health administrative costs study on 1999 data and have published other studies comparing hospital administrative costs in the U.S. and other countries.

Himmelstein says his team’s estimates of total U.S. administrative costs in the Annals study are likely conservative. When estimating physicians’ administrative costs, the researchers relied on a 2011 study of time spent by physicians and their staffs interacting with insurers. And he notes that while 2017 data was often the latest available when they were conducting this study, 2018 health spending numbers have since come out showing further increases in insurance overhead.

“We can afford universal coverage with a single payer plan, not just universal coverage but first dollar coverage for everybody in our country if we adopted a single-payer Medicare for all approach,” Himmelstein says. “If you’re going to cover everybody without getting those savings you’re going to have to spend more or you’re going to have to have big co-payments and deductibles that deter people from getting the care that they actually need.”

It is more than likely that Democratic candidates for the 2020 presidential election will propose some type of public health insurance plan. In one of two Commonwealth Fund–supported articles in Health Affairs discussing potential Democratic and Republican health care plans for the 2020 election, national health policy experts Sherry Glied and Jeanne Lambrew assess the potential impact and trade-offs of three approaches:

The authors find trade-offs in each type of public plan. First, a single-payer system would significantly increase the federal budget and require new taxes, a politically challenging prospect. On the other hand, federal spending might decrease if a public plan were added to the marketplace or if public elements were added to private plans. In 2013, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that a public plan, following the same rules as private plans, would reduce federal spending by $158 billion over 10 years, while offering premiums 7 percent to 8 percent lower than private plans. A single-payer approach would lower administrative costs and profits, and likely reduce health care prices as well. By assuming control over the financing of health care, the federal government could reduce administrative complexity and fragmentation. On the flip side, the more than 175 million Americans who are privately insured would need to change insurance plans.

A public–private choice model would help ensure that an affordable health plan option is available to Americans. While politically appealing, this option presents implementation challenges: covered benefits, payment rates, and risk-adjustments all need to be carefully managed to ensure a fair but competitive marketplace. A targeted choice option might be adopted by candidates interested in strengthening the ACA marketplaces in specific regions or for specific groups (as with the Medicare at 55 Act). It would benefit Americans whose current access to affordable coverage is limited, but the same technical challenges associated with a more comprehensive choice model would apply.

Finally, to lower prices for privately insured individuals, public plan tools such as deployment of Medicare-based rates could be applied to private insurance, either across the board or specifically for high-cost claims, prescription drugs, or other services. The major challenge here is setting prices that would appropriately compensate providers.

Under the ACA, the percentage of Americans who had health insurance had reached an all-time high (91 percent) in 2016, an all-time high, and preexisting health conditions ceased to be an obstacle to affordable insurance. But Americans remain concerned about high out-of-pocket spending and access to providers, and fears over losing preexisting-condition protections have grown. While most Democratic presidential candidates will likely defend the ACA and seek to strengthen it, most recognize that fortifying the law will not be enough to cover the remaining uninsured, rein in rising spending, and make health care more affordable.

While the health reform proposals of Democratic candidates in 2020 will likely differ dramatically from those of Republican candidates, recent grassroots support for the ACA’s preexisting condition clause may indicate a willingness by both political parties to support additional government intervention in private insurance markets.

https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/health-care-2019-year-review

Health care was front and center for policymakers and the American public in 2019. An appeals court delivered a decision on the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA’s) individual mandate. In the Democratic primaries, almost all the presidential candidates talked about health reform — some seeking to build on the ACA, others proposing to radically transform the health system. While the ACA remains the law of the land, the current administration continues to take executive actions that erode coverage and other gains. In Congress, we witnessed much legislative activity around surprise bills and drug costs. Meanwhile, far from Washington, D.C., the tech giants in Silicon Valley are crashing the health care party with promised digital transformations. If you missed any of these big developments, here’s a short overview.

1. A decision from appeals court on the future of the ACA: On December 18, an appeals court struck down the ACA’s individual mandate in Texas v. United States, a suit brought by Texas and 17 other states. The court did not rule on the constitutionality of the ACA in its entirety, but sent it back to a lower court. Last December, that court ruled the ACA unconstitutional based on Congress repealing the financial penalty associated with the mandate. The case will be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the timing of the SCOTUS ruling is uncertain, leaving the future of the ACA hanging in the balance once again.

2. Democratic candidates propose health reform options: From a set of incremental improvements to the ACA to a single-payer plan like Medicare for All, every Democratic candidate who is serious about running for president has something to say about health care. Although these plans vary widely, they all expand the number of Americans with health insurance, and some manage to reduce health spending at the same time.

3. Rise in uninsured: Gains in coverage under the ACA appear to be stalling. In 2018, an estimated 30.4 million people were uninsured, up from a low of 28.6 million in 2016, according to a recent Commonwealth Fund survey. Nearly half of uninsured adults may have been eligible for subsidized insurance through ACA marketplaces or their state’s expanded Medicaid programs.

4. Changes to Medicaid: States continue to look for ways to alter their Medicaid programs, some seeking to impose requirements for people to work or participate in other qualifying activities to receive coverage. In Arkansas, the only state to implement work requirements, more than 17,000 people lost their Medicaid coverage in just three months. A federal judge has halted the program in Arkansas. Other states are still applying for waivers; none are currently implementing work requirements.

5. Public charge rule: The administration’s public charge rule, which deems legal immigrants who are not yet citizens as “public charges” if they receive government assistance, is discouraging some legal immigrants from using public services like Medicaid. The rule impacts not only immigrants, but their children or other family members who may be citizens. DHS estimated that 77,000 could lose Medicaid or choose not to enroll. The public charge rule may be contributing to a dramatic recent increase in the number of uninsured children in the U.S.

6. Open enrollment numbers: As of the seventh week of open enrollment, 8.3 million people bought health insurance for 2020 on HealthCare.gov, the federal marketplace. Taking into account that Nevada transitioned to a state-based exchange, and Maine and Virginia expanded Medicaid, this is roughly equivalent to 2019 enrollment. In spite of the Trump administration’s support of alternative health plans, like short-term plans with limited coverage, more new people signed up for coverage in 2020 than in the previous year. As we await final numbers — which will be released in March — it is also worth noting that enrollment was extended until December 18 because consumers experienced issues on the website. In addition, state-based marketplaces have not yet reported; many have longer enrollment periods than the federal marketplace.

7. Outrage over surprise bills: Public outrage swelled this year over unexpected medical bills, which may occur when a patient is treated by an out-of-network provider at an in-network facility. These bills can run into tens of thousands of dollars, causing crippling financial problems. Congress is searching for a bipartisan solution but negotiations have been complicated by fierce lobbying from stakeholders, including private equity companies. These firms have bought up undersupplied specialty physician practices and come to rely on surprise bills to swell their revenues.

8. Employer health care coverage becomes more expensive: Roughly half the U.S. population gets health coverage through their employers. While employers and employees share the cost of this coverage, the average annual growth in the combined cost of employees’ contributions to premiums and their deductibles outpaced growth in U.S. median income between 2008 and 2018 in every state. This is because employers are passing along a larger proportion to employees, which means that people are incurring higher out-of-pocket expenses. Sluggish wage growth has also exacerbated the problem.

9. Tech companies continue inroads into health care: We are at the dawn of a new era in which technology companies may become critical players in the health care system. The management and use of health data to add value to common health care services is a prime example. Recently, Ascension, a huge national health system, reached an agreement with Google to store clinical data on 50 million patients in the tech giant’s cloud. But the devil is in the details, and tech companies and their provider clients are finding themselves enmeshed in a fierce debate over privacy, ownership, and control of health data.

10. House passes drug-cost legislation: For the first time, the U.S. House of Representatives passed comprehensive drug-cost-control legislation, H.R. 3. Reflecting the public’s distress over high drug prices, the legislation would require that the government negotiate the price of up to 250 prescription drugs in Medicare, limit drug manufacturers’ ability to annually hike prices in Medicare, and place the first-ever cap on out-of-pocket drug costs for Medicare beneficiaries. This development is historic but unlikely to result in immediate change. Its prospects in the Republican–controlled Senate are dim.

Just days after a landslide election victory for the Conservative Party, Britain’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson just made a massive and bold announcement: He’ll get laws passed to guarantee plenty of cash for the state-run healthcare system.

The official announcement will likely come Thursday when the Queen, who is the official head of state, will reopen Parliament and outline the coming legislative agenda. Tucked within her speech will be a call for £34 billion ($45 billion) in annual taxpayer money for the National Health Service (NHS).

While other countries embrace their private health systems, the British love their publicly funded NHS, an employer of 1.5 million people, which services the population of 66 million. In general, the people are concerned about the quality of care provided by the NHS and look to the government for solutions, says Mary Macleod, a senior client partner for Korn Ferry’s Board and CEO Services practice and a former Conservative Party MP. “The NHS does become a bit of a political football,” she says. “And to a large extent, everyone in the UK feels that they are stakeholders in it.”

The pledge to secure NHS money will likely bolster Johnson’s political leadership versus the opposition Labour Party. And the move also neutralizes critics that have barraged the Conservative Party with allegations that it would sell parts of the NHS to foreign investors. In other words, pushing a new funding law through Parliament could partially neutralize political opponents.

But the politics of the matter is only part of the announcement’s strength, Macleod says. Promising the NHS years of generous financing will allow the organization to develop a strategy for how it will care for the country’s population for years into the future. In short, Macleod says, it sends a message to the NHS leadership: You can get busy now. “If you now know you are getting the funding, you can plan ahead,” she says.

Johnson’s lack of specifics about how the NHS should spend the money could be a strength. In a sense, he has empowered the organization’s leadership to make the decisions that they deem suitable. “What the prime minister is not doing is defining the solutions,” Macleod says. But she also notes that he will want results in the form of improved service from the organization. “He will hold them accountable,” she says.

While there are benefits when leaders take bold steps, there are also risks, says Christina Harrington, Korn Ferry’s head of advisory services in Stockholm, Sweden. She says it is good for leaders to act quickly and with conviction, as the public expects that of its leaders. But that alone isn’t enough. She says the problem comes when there’s too much ego involved. “You need an egoless conviction to drive a decision making the greater good,” she says.

Ideally, the driver of proposed changes needs to have a long-term vision of something better than the current situation. If that vision is lacking, then the leader may lack the required stamina to get the job done. Indeed, if headline-grabbing is all that the boss wants, then he or she might wind up doing a U-turn. “If there isn’t a long-term vision, then another fast decision may come in the other direction,” Harrington says. “And that’s what we see a lot of.”

https://news.gallup.com/poll/268985/americans-favor-private-healthcare-system.aspx

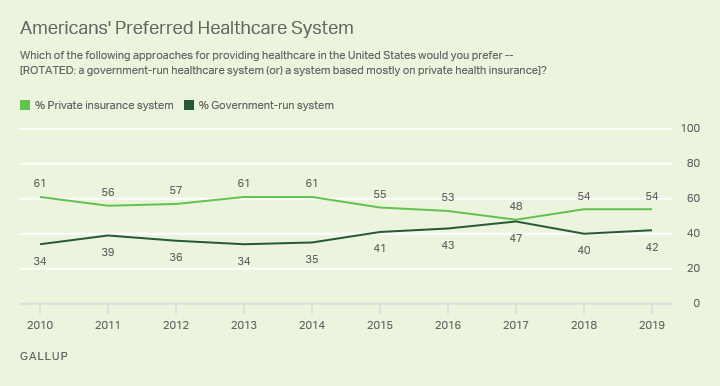

Americans continue to prefer a healthcare system based on private insurance (54%) over a government-run healthcare system (42%). Support for a government-run system averaged 36% from 2010 to 2014 but has been 40% or higher each of the past five years.

These results are based on Gallup’s annual Health and Healthcare poll, conducted Nov. 1-14. Although more Americans have warmed to the idea of a greater government role in paying for healthcare, it remains the minority view in the U.S. This could create a challenge in a general election campaign for a Democratic presidential nominee advocating a “Medicare for All” or other healthcare plan that would greatly expand the government’s role in the healthcare system.

Democratic candidates’ plans for greater government involvement in healthcare are, however, consistent with the views of their party’s base. Since 2015, after most of the Affordable Care Act’s provisions had gone into effect, an average of 65% of Democrats have favored a government-run system.

Over the same period, Republicans have been overwhelmingly opposed to a government-run system, with an average of 13% preferring that approach while 84% have wanted to retain a private system.

Independents have been closely divided in recent years, but in 2019 tilt more toward a private (50%) than a government-run (45%) system.

Compared with the five-year period spanning the ACA’s passage and implementation from 2010 to 2014, support for a government-run system has increased among all party groups, with larger increases among independents (10 percentage points) and Democrats (seven points) than among Republicans (four points).

| 2010-2014 | 2015-2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democrats | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System based on private insurance | 36 | 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government-run system | 58 | 65 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Independents | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System based on private insurance | 58 | 49 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government-run system | 36 | 46 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Republicans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System based on private insurance | 88 | 84 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government-run system | 9 | 13 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GALLUP | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

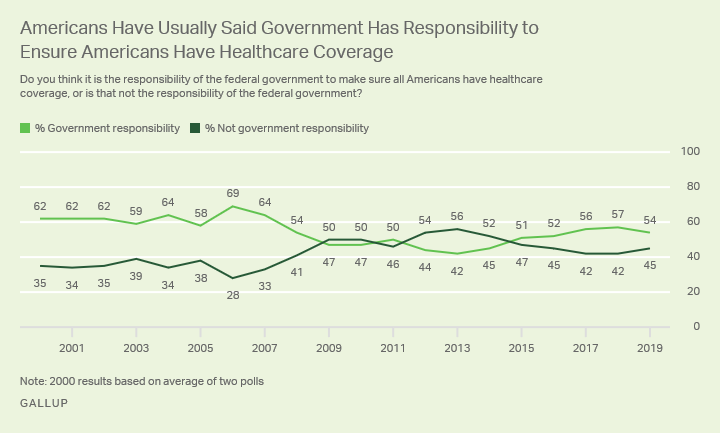

While Americans tend not to favor government-run healthcare, they do believe the federal government has a responsibility to ensure that all Americans have healthcare coverage. In the current survey, 54% hold this view, while 45% say it is not the government’s responsibility.

Recent support for the government having responsibility for ensuring healthcare coverage is not as high as it was from 2001 to 2007, when more than six in 10 Americans commonly expressed that opinion.

By contrast, from 2009 to 2014 — when the Obama administration and congressional Democrats developed, passed and implemented the Affordable Care Act — fewer Americans thought the government should ensure everyone has healthcare coverage. During that period, between 42% and 50% thought the government had that responsibility, the lowest measures in Gallup’s trend.

Between 2009 and 2014, the percentages of Republicans and independents who thought the government should be responsible for ensuring healthcare coverage dropped at least 20 points, with a smaller eight-point drop among Democrats.

Democrats’ views are now back to where they were before 2009, while independents and especially Republicans have yet to return to prior levels, though independents are back above the majority level.

| 2001-2008 | 2009-2014 | 2015-2019 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democrats | 80 | 72 | 80 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Independents | 64 | 44 | 56 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Republicans | 38 | 16 | 21 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. adults | 62 | 46 | 54 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| GALLUP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Americans have complex views on healthcare, with a majority saying the government should make sure everyone has coverage — but not necessarily pay for it through a government-run system. The Affordable Care Act was essentially an attempt to bridge these preferences by making coverage available to all through government-backed health insurance exchanges, but allowing those with insurance through an employer or other means to keep it.

Still, the law itself has been controversial, and Americans are currently as likely to disapprove of it as to approve. As such, it is fair to question to what extent Americans would embrace Democratic attempts to move to a healthcare system that goes further than the ACA does, or to support further Republican attempts to dismantle the law.

Healthcare is an issue that directly affects all Americans. Republican and Democratic political leaders have very different ideas about what healthcare policy should be. Additionally, the Democratic presidential campaign has revealed that even candidates in the same party can disagree on the best ways to address the U.S. healthcare system. With little consensus on the best way to approach healthcare policy, it promises to remain a key issue in U.S. politics and elections for the foreseeable future.

Fixing U.S. Healthcare blog’s two-year anniversary is a good time to take stock of what has changed in our approach to fixing U.S. healthcare. And a good time to review highlights of the last year.

Elevator Pitch for Fixing U.S. Healthcare

Let’s start with an “elevator pitch” summary:

The U.S. healthcare system has outgrown itself, now comprising almost 20% of the gross domestic product and still rising. It delivers ever more treatments that have diminishing “marginal benefit.” It does so at a cost far beyond the treatments’ true value to either individuals or to society, in all too many cases. And at prices double those in other developed countries. Now these costs are biting into the average family’s wallets. In 1994, the Oregon Health Plan took control of healthcare and managed its costs for 8 years by combining cost-benefit analysis with well-cultivated public engagement. This would be a good starting place for fixing U.S. healthcare. But 25 years later, this approach alone would not be sufficient. Powerful interests have now rigged the healthcare system for profits, not health. I conclude that only a grassroots movement to harness the full political, social, legal, economic and ethical weight of the federal government can encircle these entrenched interests and rein them in. There are several models for U.S. healthcare reform that could fall squarely within American tradition and pragmatism.

Changes in this Blog’s Approach

Let’s look at how this blog’s messages have evolved this year.

Updated message: Relentless increases in U.S. spending on healthcare do indeed reduce individual households’ disposable income, especially as households pay ever more of the share of healthcare costs. Healthcare costs also do eat into corporate profits, and blunt international competitiveness. However, healthcare spending is not necessarily a drag on the economy. Rather, it is now a major component of our national economy, accounting for 18.3% of total gross domestic product. This is because the U.S. has evolved into a post-industrial services-oriented economy. There is nothing inherently problematic about healthcare services in this kind of economy. The problem, however, is that excessive healthcare spending is diverting human and financial resources away from other priorities, such as education, research, infrastructure, housing. Furthermore, the marginal benefit of more healthcare spending is dwindling, while the unrealized value of deferred investment in these other priorities is growing – mounting opportunity costs.

Updated message: Economist Larry Summers dismisses the idea of an impending fiscal calamity. He explains that the “real” interest rate (nominal minus inflation) has been at historic low levels for the last two decades, resulting in no increase on the actual proportionate amount paid to service the debt. Nevertheless, he cautions federal budgeters not to deepen the debt any further, but rather pay as we go for any new programs. Thus, the reasons to fix U.S. healthcare are not to avoid national disaster, but rather to improve worker productivity, rebalance fiscal priorities, and promote societal cohesion and business climate.

Updated message: Excessive healthcare spending is indeed driven by administrative complexity (estimated at $265.6 billion annually) and to a lesser degree by low-marginal-benefit treatments (estimated at $75.7 billion to $101.2 billion) (2012-2019 data). Other elements of non-costworthy, wasted spending are:

But the other big driver of over-spending is pricing failure in imperfect markets, amounting to $230.7 billion to $240.5 billion.

Updated message: Given the prominence of market and pricing failures, this blog concludes that healthcare business interests, and their professional and political allies, have knowingly and willfully coopted healthcare for the purpose of profits. These interests have superseded the health of the public, often undermine patient-centered care, and, at times, result in actual harm.

Updated message: Since the system is rigged by powerful, well-financed interests, it can be fixed only by the full faith and clout of the federal government responding to an informed grassroots movement. The most likely format for healthcare reform would be gradual but deliberate transition to a single-payer system. This would then be followed by systematic remedies to the 6 categories of unjustified “wasteful” spending, including technology assessment using cost-benefit analysis.

https://www.politico.com/news/2019/11/19/gavin-newsom-california-health-care-2020-071403

California’s governor discovered that single-payer is a better political slogan than policy prescription, but he may have found a path to help Democrats get there anyway.

A year and a half ago, Gavin Newsom was in the same place as Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, running in a tough Democratic primary and vowing “it’s about time” for a single-payer health care system while dismissing his critics as “can’t-do Democrats” who refuse to think big.

Now he’s in a different place.

The sleek businessman with the wavy pompadour has changed his rhetoric and slowed his pace. “These things take time,” he acknowledged after his primary victory.

As governor, Newsom’s health care program has been more incremental than promised, annoying some allies in the single-payer movement while winning some unexpected praise from industry groups. But he also may have found something larger than his own agenda: A health care path that builds on past successes, enacts fresh reforms and may eventually lead to a single-payer system — without the political earthquake that so many predict under Sanders’ bill or Warren’s financing plan.

Newsom’s is by far the most relevant — and revelatory — experiential test of the Democratic health care ideas that will be so hotly debated on the Atlanta debate stage Wednesday night. And it offers something for everyone in the race to chew on: A testament to the power that a promise of a single-payer system can have in galvanizing the party’s base; the unforgiving realities that make a quick conversion to single-payer practically, and probably politically, impossible; and a way for a leader to win broader support for incremental steps that — if pursued diligently enough — could lead to universal coverage.

“This is the signature issue of the progressive left, and it’s absolutely driven by what’s happening in California,” said Doug Herman, a Democratic strategist based in Los Angeles, who attests to the appeal of single-payer as an issue. “‘Medicare for All’ could help Bernie and Elizabeth in the Democratic primary the same way it helped Gavin Newsom win the primary in California. But the deeper you go, the harder it is to explain how you’re going to pay for it.”

Newsom’s alternative steps include a return of the individual mandate requiring people to buy insurance or pay a tax penalty; stricter coverage requirements on mental health parity; expanded subsidies to help low- and middle-income people purchase coverage; more Medicaid spending to cover undocumented immigrants; and the creation of a much larger state-operated group-purchasing plan to drive down prescription drug costs.

These will be followed, if Newsom sticks to his intentions, by additional reforms generated by a 2020 commission of stakeholders that could lead to a much more highly regulated system. And that, some health experts believe, can put him on the doorstep of the Democrats’ Holy Grail: a universal, single-payer system.

“The governor continues to insist that we move forward towards a system that will cover everyone, that will be more affordable and that will be high quality. Single-payer is one point on the horizon to help to get us there,” top Newsom adviser Daniel Zingale told POLITICO. “Folks who are die-hard proponents of single-payer should not despair — that continues to be a guiding beacon for where we’re trying to go.”

* * *

Speaking to a home state crowd of more than 4,000 liberal activists in San Diego in early 2018, Newsom, the dynamic former San Francisco mayor who had spent eight years as lieutenant governor waiting for his chance at the top job, took a shot at his chief primary opponent, former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who was on a crusade to convince voters that single-payer was too expensive and impossible to achieve in California.

“My opponents, they call it snake oil. I call it single-payer,” Newsom said, borrowing a phrase Villaraigosa had employed to criticize Newsom’s lack of specifics in his health care agenda.

“It’s about access, it’s about affordability — it’s about time, Democrats,” Newsom said, buoyed by an electric, cheering crowd a few months before the primary election. “If these can’t-do Democrats were in charge, we would have never had Medicare and Social Security.”

Newsom’s early embrace, both of Sanders’ Medicare for All proposal and a $400 billion single-payer health care bill propped up in the state Legislature by the influential California Nurses Association, earned Newsom highly coveted backing from Sanders supporters and other skeptics on the left who worried he was too moderate.

He has long cultivated an image as a political risk-taker willing to battle his own party, in earlier eras pushing gay marriage and legalization of marijuana to the forefront of the Democratic agenda in California.

Newsom said his single-payer message was about “more than a political campaign,” it was about “Democrats acting like Democrats” in a battle for the soul of America against “a president that doesn’t have one.”

“Democrats do not succeed by playing it safe,” Newsom said in the campaign. He went on to defeat Villaraigosa by more than 20 points, and barely flinched at the general election challenge from Republican real estate investor John Cox.

“It was an ideological purity test, and Newsom won it,” said Mike Madrid, a Sacramento-based Republican strategist who led Villaraigosa’s campaign. “Health care is something that has defined the Democratic Party since at least the 1970s, but this was new. I was shocked to see the desire Democratic primary voters had to be lied to.”

After the primary, Newsom largely ignored his Republican opponent, instead pouring time and resources into helping down-ticket Democratic candidates beat Republicans in House and state legislative districts. Democrats ended up unseating six Republicans in the Legislature, solidifying its Democratic supermajority, and flipping seven Republican-held battleground seats in the U.S. House.

Andrew Acosta, a Sacramento-based political consultant, said disdain for President Donald Trump fueled those races, but that Newsom did help fire up the Democratic base in traditional Republican strongholds, including in the Central Valley and Orange County.

“I don’t think he was ever in any trouble with Cox, so he was able to do other things,” Acosta told POLITICO.

Newsom’s fiercest allies, meanwhile, were focused on keeping him committed to single-payer. The California Nurses Association and others on the left were growing increasingly anxious that he’d moved too far to the middle, even as they pumped money into a campaign bus with the slogan: “Nurses trust Newsom.”

“He did not run on being an incrementalist governor,” said Stephanie Roberson, chief lobbyist for the California Nurses Association in Sacramento. “If he bit off more than he can chew, he should say that.”

She referenced a series of single-payer campaign promises Newsom had made in seeking their support early in his campaign. “I’m a Californian. I don’t like waiting,” Newsom said early on. “When I’m governor, I will not wait for federal action. … I’m tired of politicians saying they support single-payer but that it’s too soon, too expensive or someone else’s problem.”

Newsom later began to shift his message away from single-payer, instead brandishing his reputation as the former two-term San Francisco mayor who took on the city’s business elite, passing a universal health care program for city residents regardless of their immigration status or ability to pay, funded in part by fees on employers.

Newsom remained firm on his goal of adopting a universal-care system for California. But single-payer would take much, much longer, if it was even possible. Weeks before the 2018 election, he argued that it was “lazy” for supporters to interpret his single-payer campaign pledge as a promise that was “achievable overnight.”

“It was always about universal health care. That’s the goal,” Newsom said. “I’ve always believed that single-payer financing is the most effective, efficient way to achieve it.”

But, he said, he’d “deeply discovered” that “single-payer financing means a million different things to a million different people.”

Democratic and Republican strategists told POLITICO that the way single-payer played out in the Newsom-Villaraigosa contest is exactly how they see the fight between the liberal presidential candidates touting Medicare for All and the moderates vowing to improve Obamacare: First, promise Medicare for All. Win the primary. Then move to the middle to pick up more middle-of-the-road voters, and start explaining how you were misunderstood all along.

“In this Trump era and a time of immense tribalism, once you start to question numbers and math, you become a heretic,” said Madrid, the Republican strategist. “We saw that in the 2018 California Democratic primary, and that’s what’s on full display in the 2020 presidential fight with Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren.”

“People didn’t want a centrist,” he said, recalling the Newsom-Villaraigosa fight. “They wanted an ideological warrior.”

* * *

They may have gotten a warrior, but some of the ideology got left behind.

Industry groups worried about Newsom coming into office. Now, they see a governor growing more moderate, one who has come around to their side and with his actions decided that building a universal health care system using the current network of payers and providers is much more realistic and politically palatable.

“The reality … and the governor knows this, is that the federal roadblocks and the state roadblocks to single-payer are real,” said Charles Bacchi, president and CEO of the California Association of Health Plans, which represents major health insurers across the state.

The first day Newsom took office, he staked out major health care priorities on the wish list of industry groups, including insurers, hospitals and doctors: Bringing back the individual health insurance mandate after a Republican-led legal fight had gutted it nationally. Higher provider reimbursement rates. An expansion of Medicaid to cover undocumented immigrants up to age 26, alleviating pressure on public hospitals and emergency rooms saddled with millions of dollars each year in uncompensated care.

Instead of cutting insurance companies out, Newsom has helped bolster their business by restoring a state-based health coverage mandate and expanding taxpayer-financed insurance subsidies for middle-class Californians — even higher than those allowed under Obamacare.

He argues such measures will further stabilize the insurance market and help more people struggling to afford coverage.

He suggested to POLITICO earlier this year that he may go even further next year by covering undocumented seniors. And he is also developing incentives, including higher provider pay, for doctors who do a better job of keeping people healthy by reducing chronic disease and improving care for mothers and babies.

He’s spearheading a massive overhaul of public-private drug purchasing, leading initiatives to drive down soaring pharmaceutical costs, he hopes, by creating a single state bulk purchasing system to negotiate deeper discounts with drugmakers. Four major counties have joined, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, Alameda and Santa Clara.

And his administration is beginning a major transformation of the state’s Medicaid program to better serve the 13 million low-income Californians who depend on it.

These initiatives could provide a workable template for a Democratic health reform agenda that presidential candidates backing single-payer should study and learn from, health policy experts say.

“You can’t just wipe out the existing system and start over,” said Joe Kutzin, who leads the health care financing team at the World Health Organization, working on establishing universal systems of care around the globe.

In most developed countries — even those held up as ideal single-payer systems — large-scale change happens more incrementally, given what Kutzin described as immense political difficulty implementing “big-bang reform.”

“Winning the argument about universal coverage first, I think, is really important,” he said. “Is there agreement that no one should become poor or die because they don’t have health coverage? The United States political system doesn’t have agreement on that basic principle, and that can get derailed by discussions about wiping out the insurance industry.”

Kutzin said the Affordable Care Act advanced the national conversation about whether health care should be a basic right — a belief that every major Democratic presidential contender says they’re for — but health care is still ingrained in the United States as an earned benefit attached to employment. And, 14 Republican-controlled states still haven’t expanded Medicaid to childless adults, while others are making it more difficult for poor people to qualify.

Like faithful single-payer advocates, Kutzin believes a uniform financing system can achieve universal coverage, and deliver it cheaper. But that ignores political realities.

“Getting to single-payer from where you are now, I’m afraid, generates a lot of resistance that risks losing the objective of universal care,” he said. “The reality, and I think the difficulty, is the system is so messy right now that almost any path to those goals are extremely painful. But standing still is really painful too.”

Tsung-Mei Cheng, a health policy researcher at Princeton who studies single-payer systems around the world, said policies Newsom has advanced can eventually lead to single-payer.

“Fix Obamacare — California is doing this,” she said. “Going from private health insurance to single-payer is a tall order. It would be different if people living in Alabama and Tennessee and all these Republican states agreed that health care is a right, but in our country, we are split.”

She said steps Newsom has taken are in line with pragmatic measures she and her late husband, Princeton economist Uwe Reinhardt, believed states could do under Obamacare. Reinhardt helped craft Taiwan’s single-payer system and broadened America’s understanding of why the United States spends more money on health care than any other industrialized country yet has worse health outcomes, in his study on uncontrolled prices.

Cheng said if California can eventually achieve universal coverage, and pass tight cost control mechanisms to reduce overall health care spending, it can serve as a model for other states and possibly, provide a state and national template for single-payer.

“You’re almost there,” she said. “The one big downside of California and Obamacare is there really isn’t any cost control mechanism, and that is necessary. If you can manage to get universal care and costs under control, then you’re there.”

But, she said, the piecemeal steps California is taking “can be a morale booster for the whole country” as Democrats and Republicans fight over the right approach.

The state has already cut its uninsured rate to about 7 percent, down 10 percentage points from the early days of Obamacare. Measures taken this year are expected to further expand coverage and access.

It could be the best any state could hope for in the immediate future. Going to all-out war with the health care industry over single-payer would be political suicide, Cheng suggested.

“Our political system allows itself to be influenced by these interest groups, and they’re very powerful,” Cheng said. “We in the United States have this congenital defect, and we’re stuck with it.”

She said regulating the market by paying all health care providers the same, regardless of coverage, and creating a public insurance option are good ideas for California to build on what the state has already done.

California is already considering those options under a single-payer health care commission established by Newsom and the state Legislature this year. Experts have said models in place in other countries can drive a more equitable, efficient delivery system for less money.

The commission is expected to begin its work in 2020, with its charge to consider a path forward on single-payer and tight cost control mechanisms, including a global budgeting system that establishes a fixed amount of health care spending for the state.

* * *

In unscripted moments last year during campaign bus tours through Los Angeles and California’s Central Valley — communities that are home to California’s largest uninsured population — Newsom alluded to reasons why he envisioned a slower path forward on single-payer.

He said he was eyeing different health care models used throughout the world, all of which included a major role for government as primary payer for health care. The so-called Bismarck model, used by Germany, Switzerland and Japan,was the most appealing for California, he said.

In general, it finances health coverage through a joint employer-employee payroll deduction, and retains a role for private doctors and hospitals. Some countries use a single government payer, while others have multiple insurers, but it provides no profits for health insurance companies and everyone is covered. A key feature is tight cost-control mechanisms on overall health care spending.

“Bismarck has more interesting tenets to what we do in California,” Newsom said last year.

He was also analyzing other systems, including a socialized medicine model under which the government owns hospitals, employs doctors and pays for health care as it does education and public safety. And he’d been studying traditional single-payer systems, like those in place in Canada and Taiwan.

Each model, he said, is better than the existing system. A key feature of any future initiative must include tight cost controls, Newsom says.

“There’s pieces of all three systems … that are easily categorized as versions of single-payer financing,” Newsom said. “Aspects of all three — that’s what we’re looking at for California.

In office, he has insisted that he remains committed to the idea of single-payer.

“I committed to this, and I want folks to know that I was serious about it,” the governor said on Inauguration Day.

Single-payer supporters and industry groups who reject the idea, meanwhile, are jockeying for inclusion in those discussions.

That could present political challenges for Newsom as he eyes larger changes ahead. His allies with the nurses union have already begun to publicly attack him, telling POLITICO earlier this year that its relationship with the governor is “on shaky ground.”

“The time is now, and I think he’s missing a moment to actually lead,” said Bonnie Castillo, executive director of the National Nurses United, which recently endorsed Sanders for president.

A California congressman with whom Newsom has had deep single-payer discussions suggested in an interview with POLITICO recently that the governor is dragging his feet.

“Our state of California should deliver on single-payer,” said Democratic Rep. Ro Khanna, who represents a vast swath of the ritzy Silicon Valley. “If California, where you have the biggest political support for the single-payer movement, isn’t going to lead, then where are we going to do it?”

Deep-pocketed industry groups such as the California Medical Association — major financial donors to Newsom during his campaign — say the governor hasn’t pleased them on everything, and they remain somewhat concerned about the longer-term prospect of single-payer, but generally they’re happy with steps he’s taken.

“When many people say single-payer, they’re really talking about a payment system that may ultimately reimburse at government-set levels that pay less than cost — that will be a challenge for hospitals,” said Carmela Coyle, president and CEO of the California Hospital Association, in an interview.

She said hospitals have “serious concerns” about politicians advancing single-payer at both the state and federal level.

“California’s hospitals will be involved and engaged,” Coyle said. “We have a tremendous opportunity to look at the issue of affordability that does not necessarily put at risk the care we’re able to provide to the population today.”

Bacchi, the president and CEO of the California Association of Health Plans, said the plans would fight back against any single-payer effort.

“What California’s health plans believe about transforming our health care system is that we should focus on building and improving the health care that’s working for millions of Californians, not starting from scratch and putting at risk the care that so many Californians rely on,” he told POLITICO. “Obviously, we’re concerned that single-payer might distract from all the other work we may need to do.”

Sara Flocks, chief lobbyist for the California Labor Federation, which backs single-payer, characterized Newsom as “untested” on health industry fights. Although he has gone after the pharmaceutical industry and soaring drug prices, that is a more politically popular stance than going after insurers, doctors and hospitals, she said.

But ultimately, if Newsom wants to control rising health care costs and expand the system in a sustainable way, that’s what he may have to do. The rough political terrain ahead could rival California’s bruising 2017 health care battle, during which the leader of the state Assembly denied a contentious single-payer bill a hearing that prevented it from advancing.

That fight, brought by the nurses, set the stage for Newsom’s forceful stance on the issue, and will continue shaping the future debate, Flocks said.

“Senate Bill 562 was a watershed moment for California,” said Flocks, an appointed member of the single-payer commission. “It opened a lot of doors to get to where we are today. What’s at stake is how we shape the national conversation.”

Newsom, faced with charges about backtracking on his single-payer promise, said last year “I haven’t lost my idealism.”

“But it’s one thing to campaign,” he added. “It’s another thing to govern.”

An industry group opposed to Medicare for All will launch a slate of new television and digital ads around the Democratic presidential debate on Thursday as part of a seven-figure campaign aimed at eroding support for a federal health-care system.

Ads will also run on Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat, according to the Partnership for America’s Health Care Future, whose membership includes drug makers, insurers, and others in the health-care industry. The organization said it will take over YouTube’s homepage following the debate.

The ad blitz show industry groups view Medicare for All as a serious threat in a 2020 election. Sens. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who are among the front-runners for the Democratic presidential nomination, back replacing the U.S. health system with a government program that would cover everyone.

The ads say Medicare for All, as well as options that let people buy into a program like Medicare, would lead to higher taxes, worse health care, and amount to government control.

Backers of Medicare for All say the proposal would lower overall U.S. health-care spending, expand coverage nationwide, and free people from costly premiums and deductibles. They say the current system lets insurers and others in the industry make unseemly profits.

The campaign, which is also opposed to buy-in options such as the proposal backed by former Vice President Joe Biden, also launched ads around the previous Democratic presidential debates.