https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-09-14/a-wall-street-giant-tapped-1-5-billion-in-federal-aid-for-its-hospitals

LifePoint’s Castleview Hospital in Price, Utah.

Private equity firm, flush with cash, sees ‘upside’ and more acquisitions.

Like hospital chains across the U.S., LifePoint Health tapped federal relief money to blunt the cost of the Covid-19 pandemic. It was a potent lifeline, a total of $1.5 billion.

But LifePoint is unusual in one respect, its owner: private equity firm Apollo Global Management, led by billionaire Leon Black.

LifePoint was certainly eligible for the money. But the extent of the federal assistance could contribute to concern in Washington over whether private equity-backed hospitals should have been. In July, the U.S. House passed a bill that would require health-care companies to disclose any private equity backing when seeking short-term loans from the federal Medicare program.

The reason for lawmakers’ concern: Private equity firms have ample access to cash. As recently as June, the Apollo fund that owns LifePoint had more than $2 billion to support its investments. Apollo, which manages $414 billion, recently told investors in an internal document that LifePoint was in such a strong market position that it was planning to make acquisitions of less fortunate hospitals.

The relief flowing to LifePoint illustrates a drawback of a government program designed to send out money quickly to every hospital, regardless of financial circumstances, according to Gerard Anderson, a health policy professor at Johns Hopkins University.

“This particular hospital system does not appear to need the money,” he said.

LifePoint and Apollo say they absolutely did. In their view, taxpayer money helped cover the soaring cost of treating Covid-19 patients and lost revenue because of the loss of fees from lucrative elective procedures. The assistance enabled the chain to retain all of its workers and provide essential service to its communities, they said.

“No health-care provider, including LifePoint, is immune to this, regardless of their ownership,” said LifePoint spokesperson Michelle Augusty.

Said an Apollo spokesperson: “Apollo is proud of LifePoint’s response to the Covid pandemic as they continue to provide vital care for both Covid and non-Covid patients.’’

LifePoint owns a far-flung collection of small-town hospitals, from Western Plains Medical Complex in Dodge City, Kansas, to Bourbon Community Hospital in Paris, Kentucky. For years, private equity has been pushing into every corner of American health care. Many medical professionals worry that these Wall Street-style investors will inevitably put profits before patients – something private equity denies.

LifePoint’s Willamette Valley Medical Center in McMinnville, Oregon.

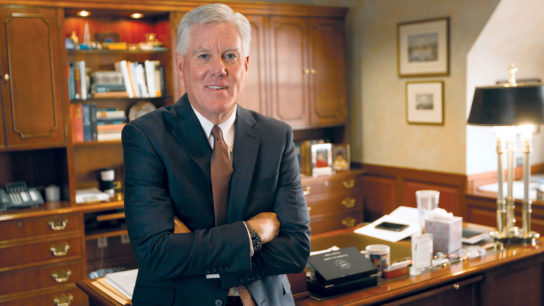

In April, LifePoint Chief Executive Officer David Dill and other hospital officials met with President Donald Trump. Dill urged Trump to keep helping hospitals, noting that LifePoint’s medical centers tend to be in the middle of the country, “smaller communities, which I know are communities very important to you,’’ according to a transcript of the meeting.

“Rural hospitals are a very important part of the infrastructure in this country and also treating the uninsured and the Medicaid population as well,’’ Dill said.

Trump pointed out that the hospitals didn’t appear to be in the “hot spots.” Dill acknowledged they were handling only “a couple hundred Covid patients.” (The company said it has now cared for almost 20,000.)

In April, the month the government started distributing assistance, LifePoint borrowed $680 million in the capital markets. It also had access to $900 million in cash and an $800 million credit line, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

By Apollo’s own account, LifePoint was doing just fine when the pandemic struck. In fact, it was thriving – and looking to expand. As of March 31, shortly before LifePoint got taxpayer dollars, Apollo’s investors were on track to double their money, internal documents show. On paper, they were sitting on a gain of more than $800 million.

“Independent hospital systems have greater difficulty weathering prolonged periods of financial stress,’’ Apollo wrote to its investors in May. “A consolidation strategy will provide meaningful upside for Apollo funds’ investment.’’

Apollo said the crisis represented an opportunity: “The coronavirus pandemic will serve as a catalyst for additional M&A opportunities given the attractive scale and overall position of the LifePoint platform.”

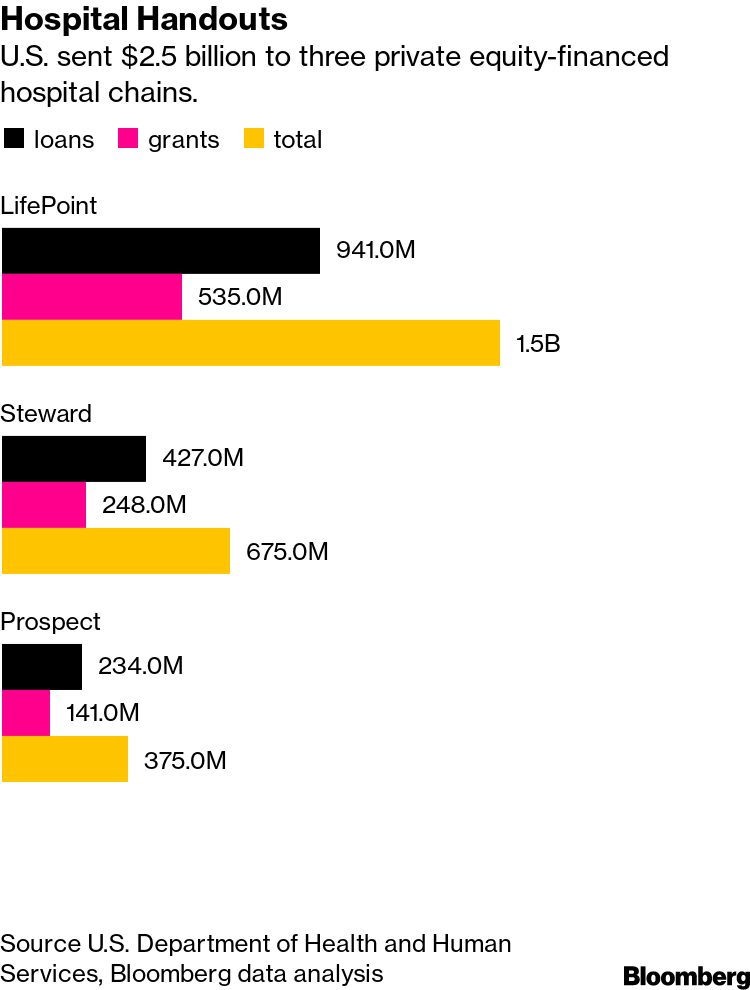

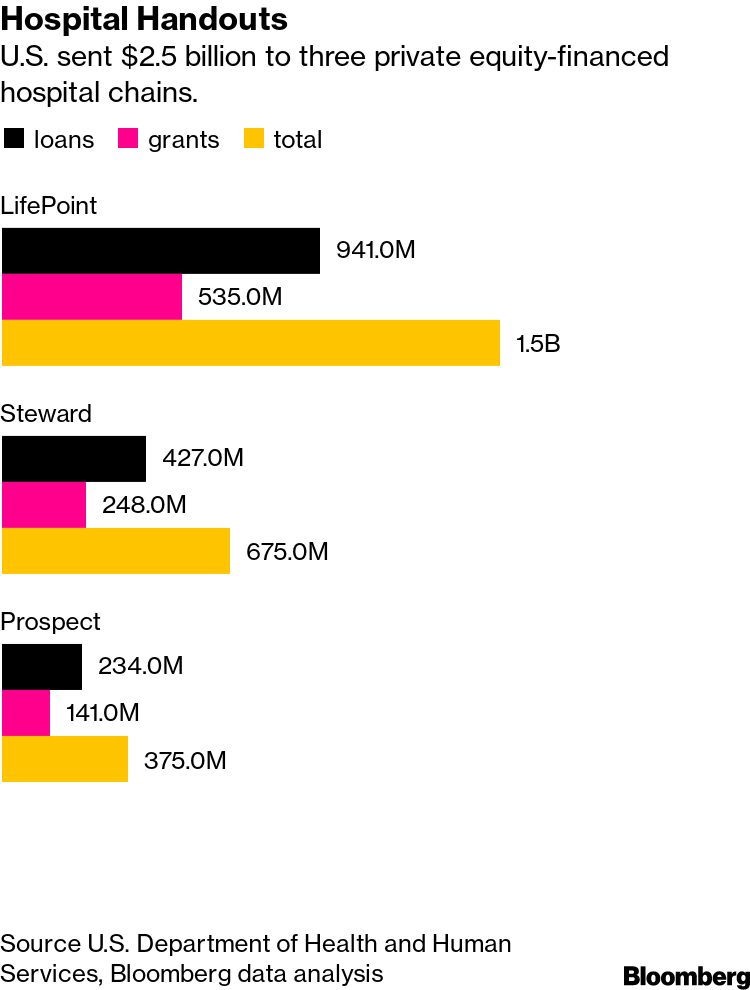

Apollo is one of three private equity firms whose hospitals, as a group, received a total of about $2.5 billion in bailout grants and loans, according to an analysis of the latest federal records. That’s a conservative figure because it doesn’t count the many smaller sums distributed to subsidiaries.

LifePoint’s UP Health System-Marquette in Michigan.

Apollo’s LifePoint hospitals received the most: $941 million in subsidized loans and $535 million in outright grants.

While Democratic lawmakers have said

such firms could have instead tapped their own cash stockpiles, private equity industry representatives have said they have a duty to manage that money in the best interests of their investors, which include public pension plans.

Apollo built its rural hospital empire through the acquisition of three regional hospital chains in 2015, 2016 and 2018. Apollo Investment Fund VIII LP owns 76% of LifePoint, which is based in Brentwood, Tennessee.

Even though many individual rural hospitals are struggling, Apollo says it can operate them more efficiently by merging them together. LifePoint now owns 88 hospitals in 29 states. It had almost $9 billion of annual revenue last year.

Apollo says that on its watch, the chain has improved its infrastructure and technology, recruited care providers and built new centers.

And for rural hospitals, Apollo argues, bigger is better.

“We continue to believe that rural hospitals can benefit from being part of a larger well-run system that enables access to greater resources and infrastructure for improved patient care,” the Apollo spokesperson said.