Cartoon – 2020 Choices

After an exhausting and contentious election campaign, and a vote count that was prolonged by enormous voter turnout and record-breaking use of early and mail-in voting, the major news networks have now made their calls. Joseph R. Biden, Jr. will be the 46th President of the United States, and Kamala D. Harris will be the first woman, and first person of color, to become Vice President. Securing an electoral victory by achieving razor-thin victories in a number of battleground states, President-elect Biden received the largest number of votes of any candidate in American history. Although the Trump campaign vowed to pursue legal challenges to the validity of the election, Biden’s win appeared to be secure.

The election results came in the midst of a dramatic acceleration of the coronavirus pandemic. Over the last week, the average number of new cases per day in the US surpassed 96,000, up 54 percent from just two weeks earlier. On Friday the nation recorded a pandemic-high 132,700 new cases, along with at least 1,220 COVID deaths. Hospitalizations were up in most states, hospital bed and workforce capacity are strained, and public health experts warned that the coming weeks and months will bring even worse news. Unsurprisingly, the pandemic was a top issue on the minds of voters. According to exit polls, however, the electorate was deeply divided on the issue: 82 percent of Biden voters cited the pandemic itself as one of the most important issues in determining their vote, with only 14 percent of Trump voters agreeing. Conversely, 82 percent of Trump voters said the economy was the most important issue on their minds, as opposed to Biden voters, only 17 percent of whom listed the economy as their top issue. Based on that data, it appears that at least one important split among the electorate was “lives” versus “livelihoods”—whether the pandemic response, or its impact on the economy, was of greatest concern.

In the coming weeks, attention is likely to turn in earnest to addressing both aspects of the issue during the lame duck period. Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) has signaled that he intends to resume negotiations on a stimulus package with Democrats in the House, whose majority was diminished in the election. At this writing, it appears likely that control of the Senate will come down to the results of two runoff elections in Georgia, and McConnell will undoubtedly want to make the case that Senate Republicans have taken decisive action to bolster the economic recovery. It’s also possible that, as part of the Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed, a coronavirus vaccine will be granted approval by the end of the year. Health officials at both federal and state levels must continue to work closely together to tackle the complex logistics of distributing and administering the vaccine, and it will be critical for the incoming administration to seek ways to collaborate with the Trump team to ensure a smooth transition of this vital work.

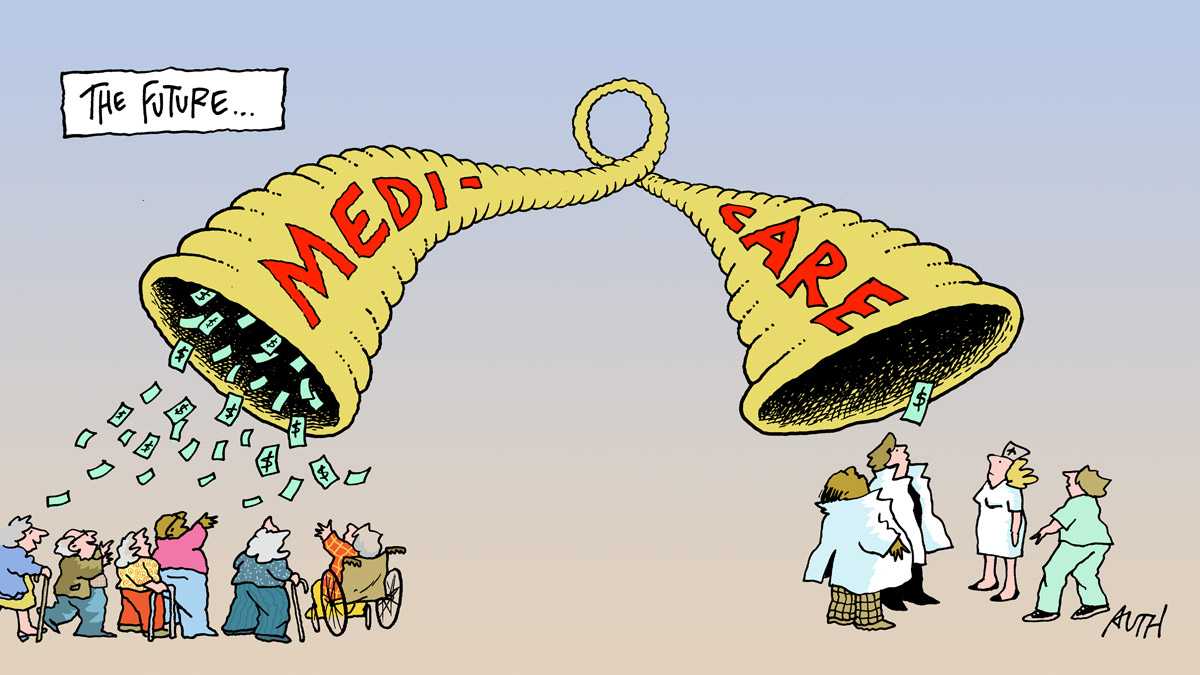

The outcome of the Senate runoffs in Georgia will determine whether the Biden administration must work with divided Congress, or an evenly split Senate in which Vice President-elect Kamala Harris casts the deciding vote. In either case, given the political realities underscored by the electoral result, it’s very unlikely than any of the more sweeping proposals in the Biden campaign platform—lowering the eligibility age for Medicare, establishing a government-run “public option” insurance plan, extending premium subsidies to middle-income workers—will advance very far. Rather, as we’ve discussed before, we’d expect a Biden administration’s first actions to focus on an enhanced federal response to managing the pandemic, including issuing a national mask mandate, enhancing efforts to augment and coordinate personal protective equipment (PPE) supply, and rejoining the World Health Organization.

As we look to the next two years, most healthcare policy changes are likely to come in the form of regulatory reform, such as reversing waivers for Medicaid programs to establish work requirements and withdrawing flexibility for short-term plans that fail to comply with the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Other Trump-era regulatory changes might continue. There’s broad bipartisan support for efforts to make value-based Medicare payment reforms more successful, to increase price transparency, and to address the issues of surprise billing and the cost of prescription drugs. But even in if Democrats beat the odds and win back control of the Senate, we believe the Biden administration will have other legislative priorities that will supersede any attempt to dramatically overhaul healthcare coverage—voting reforms, climate change legislation, immigration reform, and long-overdue infrastructure investments.

Unless, that is, the Supreme Court throws a spanner in the works by overturning the ACA. Should the Court rule that the individual mandate is not severable from the rest of the law, and that the entire ACA is unconstitutional, the new administration would be forced to take quick action to protect coverage and insurance protections for millions of Americans. In that event, healthcare would rocket to the top of the agenda. Either the Biden team would be forced to find a compromise solution that could pass a divided Congress, or (if Harris is the tie-breaking vote) find a way to use the budget reconciliation process to address coverage. That potential drama lies months in the future, as we won’t know the outcome of the case until next spring. We’ll monitor the oral arguments in the ACA case closely, and let you know what we hear, and what we think it means for the future of the case.

In the coming weeks, we’ll be watching for answers to some of the big healthcare questions that lie ahead: How will the Trump administration handle the worsening pandemic situation in the 75 days between now and Inauguration Day? Will any new stimulus package include additional economic relief for healthcare providers? When and how will a COVID vaccine become widely available? And perhaps most importantly, what toll will the “third wave” of the pandemic take on a nation already exhausted by a difficult year, and a bitter political fight? Surely one reason to be optimistic is that, having turned out to vote in the largest numbers in a century, Americans are more engaged than ever in finding a way forward amid the problems that confront us. Let’s hope our political leaders from across the ideological spectrum will rise to the occasion, and meet this difficult moment with positive, constructive solutions.

https://us.newschant.com/business/dr-philip-lee-is-dead-at-96-engineered-introduction-of-medicare/

Dr. Philip R. Lee, who as a number one federal well being official and fighter for social justice below President Lyndon B. Johnson wielded authorities Medicare money as a cudgel to desegregate the nation’s hospitals within the Sixties, died on Oct. 27 in a hospital in Manhattan. He was 96.

The trigger was coronary heart arrhythmia, his spouse, Dr. Roz Lasker, mentioned.

From his workplace at the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, because the assistant secretary for well being and scientific affairs from 1965 to 1969, Dr. Lee engineered the introduction of Medicare, which was established for older Americans in 1965, one 12 months after Johnson had bulldozed his landmark civil-rights invoice via Congress.

“To Phil, Medicare wasn’t just a ‘big law’ expanding coverage; it was a vehicle to address racial and economic injustice,” his nephew Peter Lee, the manager director of Covered California, which runs the state’s well being care market below the Affordable Care Act, was quoted as saying in a tribute by the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Lee was the college’s chancellor from 1969 to 1972, after leaving the Johnson administration.

Dr. Lee’s use of Medicare funding to desegregate hospitals “changed the economic lives of millions of seniors,” Mr. Lee added.

Provisions within the Medicare laws subjected 7,000 hospitals nationwide to guidelines barring discrimination towards sufferers on the premise of race, creed or nationwide origin. The regulation required equal remedy throughout the board — from medical and nursing care to mattress assignments and cafeteria and restroom privileges — and barred discrimination in hiring, coaching or promotion.

Before the regulation took impact in 1966, fewer than half the hospitals within the nation met the desegregation commonplace and fewer than 25 p.c did within the South.

“I remember during one of my visits,” Dr. Lee instructed the journal of the American Society on Aging in 2015, “a cardiologist at Georgia Baptist Hospital told me, ‘Well, you know, Dr. Lee, if I put a nigger in with one of my white patients, it would kill the patient. My patient would die of a heart attack.’”

By February 1967, a 12 months or much less after many of the regulation’s provisions had taken impact, 95 p.c of hospitals have been compliant, Dr. Lee mentioned.

“He was largely responsible for that effort,” mentioned Professor David Barton Smith of Drexel University and writer of “The Power to Heal: Civil Rights, Medicare and the Struggle to Transform America’s Health System” (2016).

Dr. Lee hailed from a household of physicians — his father and 4 siblings have been medical doctors — and whereas working within the Palo Alto Medical Clinic (now the Palo Alto Medical Foundation), which his father based, he noticed firsthand the consequences on the poor and the aged of insufficient well being care and the shortage of insurance coverage protection.

As early as 1961, he was a guide on growing older to the Santa Clara Department of Welfare in California, and as a member of the American Medical Association and a Republican at the time, he defied each the A.M.A. and his celebration in testifying earlier than Congress on behalf of a precursor to Medicare that might have helped pay for hospital and nursing dwelling care via Social Security for sufferers over 65.

Dr. Lee was branded a socialist and a Communist (irrespective of that he had served as a physician within the Korean War).

In 1987, after main the University of California, San Francisco, and heading well being coverage and analysis packages there as a professor of social drugs, he additional riled fellow physicians when, as chairman of Congressional fee, he really helpful a standardized nationwide restrict on how a lot medical doctors enrolled within the Medicare program, with an enormous pool of sufferers obtainable to them, might cost above a set schedule.

He was referred to as again to Washington in 1993, once more to be an assistant secretary, this time of the renamed Department of Health and Human Services below the Clinton administration. Serving till 1997, he suggested the White House on its in the end failed effort on well being care reform.

In 2015 he endorsed the Obama administration’s Affordable Care Act and steered that the nation might go even additional in guaranteeing common well being care.

“In 1967, President Johnson said we would continue to work until equality of treatment is the rule,” Dr. Lee wrote in Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging. “By making Medicare an option for all Americans, the kind of care I receive could be available to everyone.”

Philip Randolph Lee was born in San Francisco on April 17, 1924, to Dr. Russell Van Arsdale Lee, who had lobbied for nationwide medical insurance as a member of a fee appointed by President Harry S. Truman, and Dorothy (Womack) Lee, an newbie musician.

His curiosity in drugs, he instructed Stanford Medicine Magazine in 2004, “began with house calls with my dad from the age of 6 or 7.”

He earned his bachelor’s and medical levels at Stanford University in 1945 and 1948. As a member of the Naval Reserve, he was on lively responsibility as a physician at the top of World War II and once more from 1949 to 1951, through the Inchon invasion in Korea. He obtained a grasp of science diploma from the University of Minnesota in 1955 and had fellowships at the Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine in New York and the Mayo Clinic.

“Phil moved from clinical medicine to health policy and then devoted his life to addressing issues at the nexus of civil rights, social justice and health,” Dr. Lasker, his spouse, mentioned in an e-mail.

His distinguished function in shaping Medicare and different federal well being insurance policies was preceded by a stint, 1963-65, as director of well being for the Agency for International Development. As chancellor of the University of California, San Francisco, he was credited with rising racial variety amongst its workers, college and pupil physique.

In 2007, the college named its Institute for Health Policy Studies, which he based in 1972, in his honor.

He was additionally lauded for his aggressive function in confronting the AIDS epidemic because the president of the newly-formed Health Commission of the City and County of San Francisco from 1985 to 1989.

The writer of a half-dozen books, Dr. Lee was an early critic of the pharmaceutical trade in “Pills, Profits and Politics” (1974, with Milton Silverman).

In swing states from Georgia to Arizona, the Affordable Care Act — and concerns over protecting preexisting conditions — loom over key races for Congress and the presidency.

“I can’t even believe it’s in jeopardy,” says Noshin Rafieei, a 36-year-old from Phoenix. “The people that are trying to eliminate the protection for individuals such as myself with preexisting conditions, they must not understand what it’s like.”

In 2016, Rafieei was diagnosed with colon cancer. A year later, her doctor discovered it had spread to her liver.

“I was taking oral chemo, morning and night — just imagine that’s your breakfast, essentially, and your dinner,” Rafieei says.

In February, she underwent a liver transplant.

Rafieei does have health insurance now through her employer, but she fears whether her medical history could disqualify her from getting care in the future.

“I had to pray that my insurance would approve of my transplant just in the nick of time,” she says. “I had that Stage 4 label attached to my name and that has dollar signs. Who wants to invest in someone with Stage 4?”

“That is no way to feel,” she adds.

After doing her research, Rafieei says she intends to vote for Joe Biden, who helped get the ACA passed in this first place.

“Health care for me is just the driving factor,” she says.

Even 10 years after the Affordable Care Act locked in a health care protection that Americans now overwhelmingly support — guarantees that insurers cannot deny coverage or charge more based on preexisting medical conditions — voters once again face contradicting campaign promises over which candidate will preserve the law’s legacy.

A majority of Democrats, independents and Republicans say they want their new president to preserve the ACA’s provision that protects as many as 135 million people from potentially being unable to get health care because of their medical history.

President Trump has pledged to keep this in place, even as his administration heads to the U.S Supreme Court the week after Election Day to argue the entire law should be struck down.

“We’ll always protect people with preexisting,” Trump said in the most recent debate. “I’d like to terminate Obamacare, come up with a brand new, beautiful health care.”

And yet the Trump administration has not unveiled a health care plan or identified any specific components it might include. In 2017, the administration joined with congressional Republicans to dismantle the Affordable Care Act, but none of the GOP-backed replacement plans could summon enough votes. The Republicans’ final attempt, a limited “skinny repeal” of parts of the ACA, failed in the Senate because of resistance within their own party.

In an attempt to reassure wary voters, Trump recently signed an executive order that asserts protections for preexisting conditions will stay in place, but legal experts say this has no teeth.

“It’s basically a pinky promise, but it doesn’t have teeth,” says Swapna Reddy, a clinical assistant professor at Arizona State University’s College of Health Solutions. “What is the enforceability? The order really doesn’t have any effect because it can’t regulate the insurance industry.”

Since the 2017 repeal and replace efforts, the health care law has continued to gain popularity.

Public approval is now at an all-time high, but polling shows many Republicans still don’t view the ACA as synonymous with its most popular provision — protections for preexisting conditions.

Democrats hope to change that.

“If you have a preexisting condition — heart disease, diabetes, breast cancer — they are coming for you,” said Biden’s running mate, California Sen. Kamala Harris, during her recent debate with Vice President Pence.

Voters support maintaining ACA’s legal protections

In key swing states, many voters say protecting preexisting conditions is their top health concern.

Rafieei, the Phoenix woman with colon cancer, still often has problems getting her treatments covered. Her insurance has denied medications that help quell the painful side effects of chemotherapy or complications related to her transplant.

“During those chemo days, I’d think, wow, I’m really sick, and I just got off the phone with my pharmacy and they’re denying me something that could possibly help me,” she says.

Because of her transplant, she will be on medication for the rest of her life, and sometimes she even has nightmares about being away and running out of it.

“I will have these panic attacks like, ‘Where’s my medicine? Oh my god, I have to get back to get my medicine?'”

Election season and talk of eliminating the ACA has not given Rafieei much reassurance, though.

“I cannot stomach politics. I am beyond terrified,” she says.

And yet she plans to head to the polls — in person — despite having a compromised immune system.

“It might be a long day. But you know what? I want to fix whatever I can,” she says.

A few days after she votes, she’ll get a coronavirus test and go in for another round of surgery.

A key health issue in political swing states

Rafieei’s home state of Arizona is emblematic of the political contradictions around the health care law.

The Republican-led state reaped the benefits of the ACA. Arizona’s uninsured rate dropped considerably since 2010, in part because it expanded Medicaid.

But the state’s governor also embraced the Republican effort to repeal and replace the law in 2017, and now Arizona’s attorney general is part of the lawsuit that will be heard by the Supreme Court on Nov. 10 that could topple the entire law.

Depending on how the Supreme Court rules, ASU’s Reddy says any meaningful replacement for preexisting conditions would involve Congress and the next president.

“At the moment, we have absolutely no national replacement plan,” she says.

Meanwhile, some states have passed their own laws to maintain protections for preexisting conditions, in the event the ACA is struck down. But Reddy says those vary considerably from state to state.

For example, Arizona’s law, passed just earlier this year, only prevents insurers from outright denying coverage — consumers with preexisting conditions can be charged more.

“We are in this season of chaos around the Affordable Care Act,” says Reddy. “From a consumer perspective, it’s really hard to decipher all these details.”

As in the congressional midterm election of 2018, Democrats are hammering away at Republican’s track record on preexisting conditions and the ACA.

In Arizona, Mark Kelly, the Democratic candidate running for Senate, has run ads and used every opportunity to remind voters of Republican Sen. Martha McSally’s votes to repeal the law.

In Georgia, Democratic challenger Jon Ossoff has taken a similar approach.

“Can you look down the camera and tell the people of this state why you voted four times to allow insurance companies to deny us health care coverage because we may suffer from diabetes or heart disease or have cancer in remission?” Ossoff said during a debate with his opponent, Republican Sen. David Purdue.

Republicans have often tried to skirt health care as a major issue this election cycle because there isn’t the same political advantage to pushing the repeal and replace argument, says Mark Peterson, a professor of public policy, political science and law at UCLA.

“It’s political suicide, there doesn’t seem to be any real political advantage anymore,” says Peterson.

But the timing of the Supreme Court case — exactly a week after election day — has somewhat obscured the issue for voters.

Republicans have chipped away at the health care law by reducing the individual mandate — the provision requiring consumers to purchase insurance — to zero dollars.

The premise of the Supreme Court case is that the ACA no longer qualifies as a tax because of this change in the penalty.

“It is an extraordinary stretch, even among many conservative legal scholars, to say that the entire law is predicated on the existence of an enforced individual mandate,” says Peterson.

The court could rule in a very limited way that does not disrupt the entire law or protections for preexisting conditions, he says.

Like many issues this election, Peterson says there is a big disconnect between what voters in the two parties believe is at stake with the ACA.

“Not everybody, particularly Republicans, associates the ACA with protecting preexisting conditions,” he says. “But it is pretty striking that overwhelmingly Democrats and Independents do — and a number of Republicans — that’s enough to give a significant national supermajority.”