https://www.propublica.org/article/100000-lives-lost-to-covid-19-what-did-they-teach-us?utm_source=pardot&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=dailynewsletter&utm_content=feature

Each person who has died of COVID-19 was somebody’s everything. Even as we mourn for those we knew, cry for those we loved and consider those who have died uncounted, the full tragedy of the pandemic hinges on one question: How do we stop the next 100,000?

The United States has now recorded 100,000 deaths due to the coronavirus.

It’s a moment to collectively grieve and reflect.

Even as we mourn for those we knew, cry for those we loved and consider also those who have died uncounted, I hope that we can also resolve to learn more, test better, hold our leaders accountable and better protect our citizens so we do not have to reach another grim milestone.

Through public records requests and other reporting, ProPublica has found example after example of delays, mistakes and missed opportunities. The CDC took weeks to fix its faulty test. In Seattle, 33,000 fans attended a soccer match, even after the top local health official said he wanted to end mass gatherings. Houston went ahead with a livestock show and rodeo that typically draws 2.5 million people, until evidence of community spread shut it down after eight days. Nebraska kept a meatpacking plant open that health officials wanted to shut down, and cases from the plant subsequently skyrocketed. And in New York, the epicenter of the pandemic, political infighting between Gov. Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio hampered communication and slowed decision making at a time when speed was critical to stop the virus’ exponential spread.

COVID-19 has also laid bare many long-standing inequities and failings in America’s health care system. It is devastating, but not surprising, to learn that many of those who have been most harmed by the virus are also Americans who have long suffered from historical social injustices that left them particularly susceptible to the disease.

This massive loss of life wasn’t inevitable. It wasn’t simply unfortunate and regrettable. Even without a vaccine or cure, better mitigation measures could have prevented infections from happening in the first place; more testing capacity could have allowed patients to be identified and treated earlier.

The COVID-19 pandemic is not over, far from it.

At this moment, the questions we need to ask are: How do we prevent the next 100,000 deaths from happening? How do we better protect our most vulnerable in the coming months? Even while we mourn, how can we take action, so we do not repeat this horror all over again?

Here’s what we’ve learned so far.

Though we’ve long known about infection control problems in nursing homes, COVID-19 got in and ran roughshod.

From the first weeks of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States, when the virus tore through the Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington, nursing homes and long-term care facilities have emerged as one of the deadliest settings. As of May 21, there have been around 35,000 deaths of staff and residents in nursing homes and long-term care facilities, according to the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation.

Yet the facilities have continued to struggle with basic infection control. Federal inspectors have found homes with insufficient staff and a lack of personal protective equipment. Others have failed to maintain social distancing among residents, according to inspection reports ProPublica reviewed. Desperate family members have had to become detectives and activists, one even going as far as staging a midnight rescue of her loved one as the virus spread through a Queens, New York, assisted living facility.

What now? The risk to the elderly will not decrease as time goes by — more than any other population, they will need the highest levels of protection until the pandemic is over. The CEO of the industry’s trade group told my colleague Charles Ornstein: “Just like hospitals, we have called for help. In our case, nobody has listened.” More can be done to protect our nursing home and long term care population. This means regular testing of both staff and residents, adequate protective gear and a realistic way to isolate residents who test positive.

Racial disparities in health care are pervasive in medicine, as they have been in COVID-19 deaths.

African Americans have contracted and died of the coronavirus at higher rates across the country. This is due to myriad factors, including more limited access to medical care as well as environmental, economic and political factors that put them at higher risk of chronic conditions. When ProPublica examined the first 100 recorded victims of the coronavirus in Chicago, we found that 70 were black. African Americans make up 30% of the city’s population.

What now? States should make sure that safety-net hospitals, which serve a large portion of low-income and uninsured patients regardless of their ability to pay, and hospitals in neighborhoods that serve predominantly black communities, are well-supplied and sufficiently staffed during the crisis. More can also be done to encourage African American patients to not delay seeking care, even when they have “innocent symptoms” like a cough or low-grade fever, especially when they suffer other health conditions like diabetes.

Racial disparities go beyond medicine, to other aspects of the pandemic. Data shows that black people are already being disproportionately arrested for social distancing violations, a measure that can undercut public health efforts and further raise the risk of infection, especially when enforcement includes time in a crowded jail.

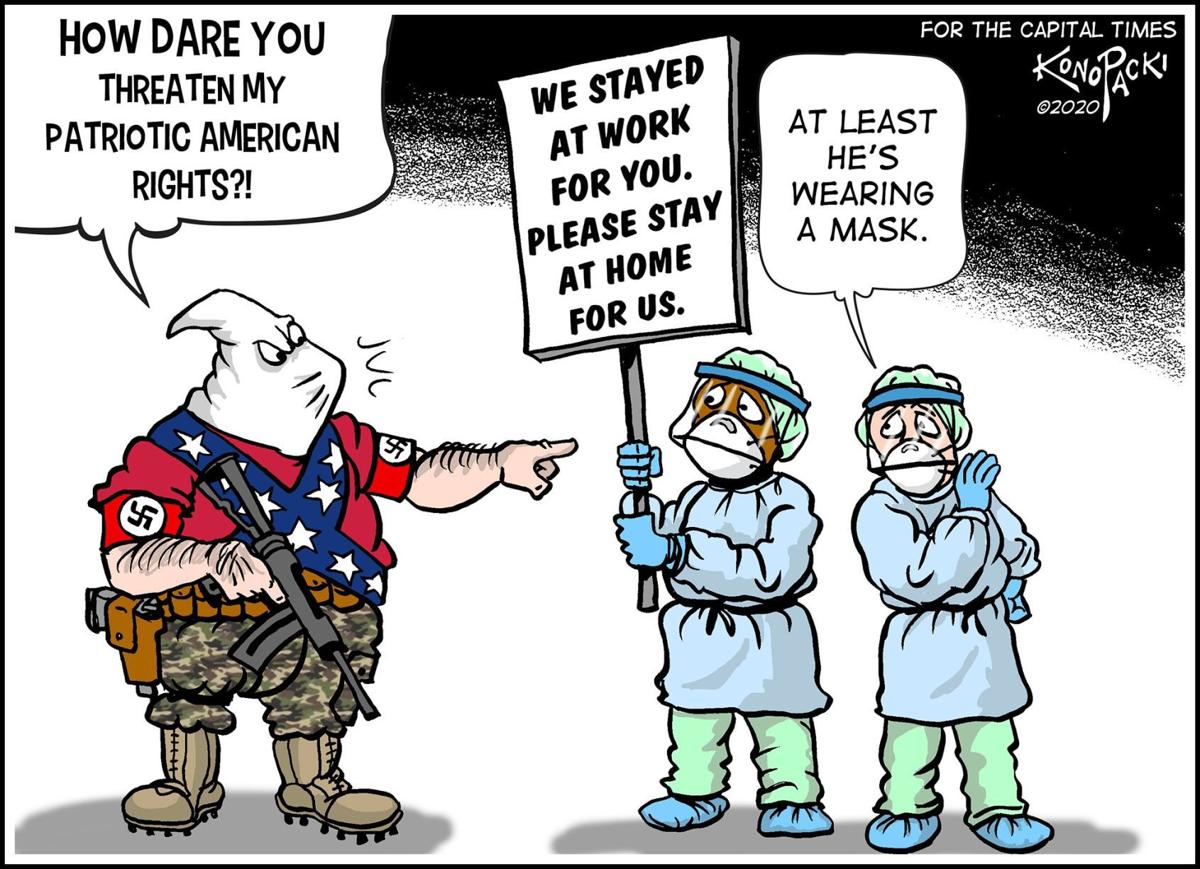

Essential workers had little choice but to work during COVID-19, but adequate safeguards weren’t put in place to protect them.

We’ve known from the beginning there are some measures that help protect us from the virus, such as physical distancing. Yet millions of Americans haven’t been able to heed that advice, and have had no choice but to risk their health daily as they’ve gone to work shoulder-to-shoulder in meat-packing plants, rung up groceries while being forbidden to wear gloves, or delivered the mail. Those who are undocumented live with the additional fear of being caught by immigration authorities if they go to a hospital for testing or treatment.

What now? Research has shown that there’s a much higher risk of transmission in enclosed spaces than outdoors, so providing good ventilation, adequate physical distancing, and protective gear as appropriate for workers in indoor spaces is critical for safety. We also now know that patients are likely most infectious right before or at the time when symptoms start appearing, so if workplaces are generous about their sick leave policies, workers can err on the side of caution if they do feel unwell, and not have to choose between their livelihoods and their health. It’s also important to have adequate testing capacity, so infections can be caught before they turn into a large outbreak.

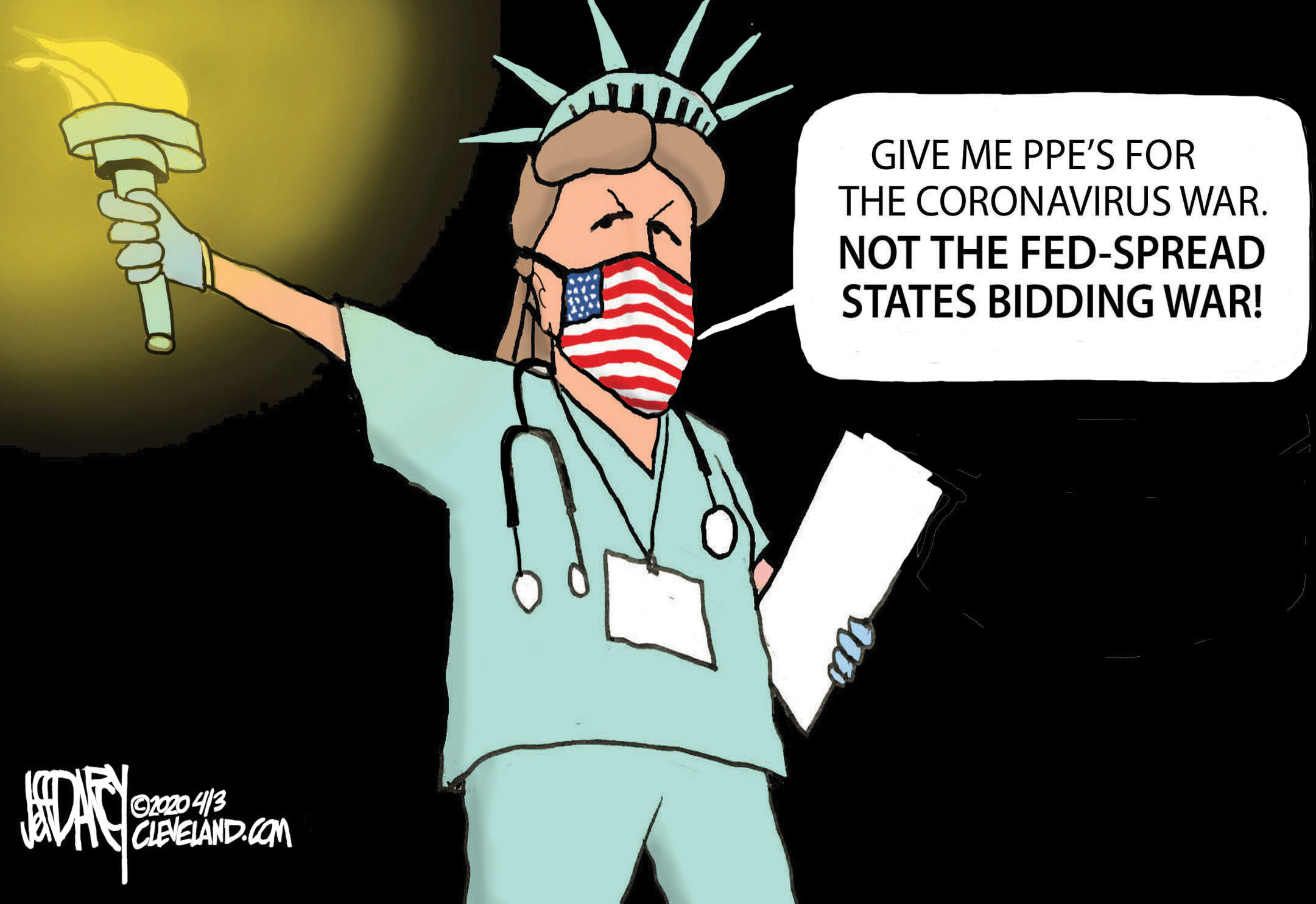

Frontline health care workers were not given adequate PPE and were sometimes fired for speaking up about it.

While health workers have not, thankfully, been dying at conspicuously higher rates, they continue to be susceptible to the virus due to their work. The national scramble for ventilators and personal protective equipment has exposed the just-in-time nature of hospitals’ inventories: Nurses across the country have had to work with expired N95 masks, or no masks at all. Health workers have been suspended, or put on unpaid leave, because they didn’t see eye to eye with their administrators on the amount of protective gear they needed to keep themselves safe while caring for patients.

First responders — EMTs, firefighters and paramedics — are often forgotten when it comes to funding, even though they are the first point of contact with sick patients. The lack of a coherent system nationwide meant that some first responders felt prepared, while others were begging for masks at local hospitals.

What now? As states reopen, it will be important to closely track hospital capacity, and if cases rise and threaten their medical systems’ ability to care for patients, governments will need to be ready to pause or even dial back reopening measures. It should go without saying that adequate protective gear is a must. I also hope that hospital administrators are thinking about mental health care for their staffs. Doctors and nurses have told us of the immense strain of caring for patients whom they don’t know how to save, while also worrying about getting sick themselves, or carrying the virus home to their loved ones. Even “heroes” need supplies and support.

What we still have to learn:

There continue to be questions on which data is lacking, such as the effects of the coronavirus on pregnant women. Without evidence-based research, pregnant women have been left to make decisions on their own, sometimes trying to limit their exposure against their employer’s wishes.

Similarly, there’s a paucity of data on children’s risk level and their role in transmission. While we can confidently say that it’s rare for children to get very ill if they do get infected, there’s not as much information on whether children are as infectious as adults. Answering that question would not just help parents make decisions (Can I let my kid go to day care when we live with Grandma?) but also help officials make evidence-based decisions on how and when to reopen schools.

There’s some research I don’t want to rush. Experts say the bar for evidence should be extremely high when it comes to a vaccine’s safety and benefit. It makes sense that we might be willing to use a therapeutic with less evidence on critically ill patients, knowing that without any intervention, they would soon die. A vaccine, however, is intended to be given to vast numbers of healthy people. So yes, we have to move urgently, but we must still take the time to gather robust data.

Our nation’s leaders have many choices to make in the coming weeks and months. I hope they will heed the advice of scientists, doctors and public health officials, and prioritize the protection of everyone from essential workers to people in prisons and homeless shelters who does not have the privilege of staying home for the duration of the pandemic.

The coronavirus is a wily adversary. We may ultimately defeat it with a vaccine or effective therapeutics. But what we’ve learned from the first 100,000 deaths is that we can save lives with the oldest mitigation tactics in the public health arsenal — and that being slow to act comes with a terrible cost.

I refuse to succumb to fatalism, to just accepting the ever higher death toll as inevitable. I want us to make it harder for this virus to take each precious life from us. And I believe we can.