A few weeks ago The Commonwealth Fund, a philanthropic organization in New York City, which keeps tabs on health care trends, released an ominous study signaling that the bedrock of the U.S. health system is in trouble.

The study found that the employer insurance market, where millions of Americans have received good, affordable coverage since the end of World War II, could be in jeopardy. The continuing rise in the costs of medical care, and the insurance premiums to pay for it, may well cause employers to make cutbacks, leaving millions of workers uninsured or underinsured, often with no way to pay for their care and the prospect of debt for the rest of their lives.

Indeed the Fund revealed that 23% of adults in the U.S. are underinsured, meaning that though they were covered by health insurance, high deductibles and coinsurance made it difficult or impossible to pay for the care they needed.

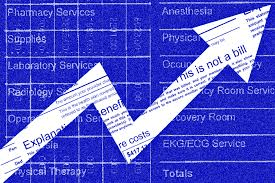

“They have health plans that don’t provide affordable access to care,” said Sara Collins, senior adviser and vice president at the Fund. “They have out-of-pocket costs and deductibles that are high relative to their income.”

This predicament has forced many to assume medical debt or skip needed care. The Fund found that as many as one-third of people with chronic conditions like heart failure and diabetes reported they don’t take their medication or fill prescriptions because they cost too much.

Others did not go to a doctor when they were sick, skipping a recommended follow-up visit or test, and did not see a specialist when one was recommended. Nearly half of the respondents reported they did not get care for an ongoing condition because of the cost. Two out of five working-age adults who reported a delay or skipped care told researchers their health problem had gotten worse. Those findings belie the narrative, deployed when changes to the system are discussed, that America has the best health care in the world, and we dare not change it.

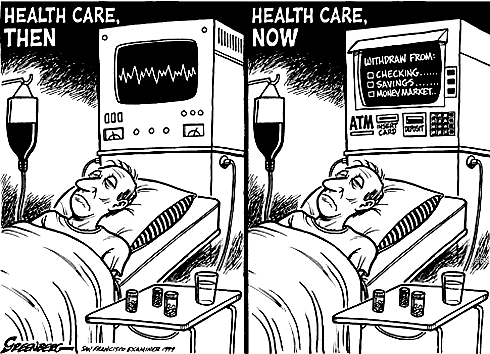

The seeds of today’s underinsurance predicament were planted in the 1990s when the system’s players decided remedies were needed to curb Americans’ appetite for medical interventions.

They devised managed care, with its HMOs, PPOs, insurance company approvals, and other restrictions that are with us today. But health care is far more expensive than it was in the ’90s, leaving patients to struggle to pay the higher prices, or, as the study shows, go without needed care.

Perhaps one of the study’s most striking findings is that a vast majority of underinsured workers had employer insurance plans, which over the decades had provided good coverage. Researchers concluded that recent cost containment measures were simply shifting more costs to workers through higher deductibles and coinsurance.

I checked in with Richard Master, the CEO of MCS Industries in Easton, Pennsylvania. We’ve talked over the years about the rising cost of health insurance for his 91 workers who make picture frames and wall decorations. This year, he was expecting a 5 to 6% increase in insurance rates.

A family plan now costs more than $39,000, he said, adding that “29% of people with employee plans are underinsured and have high out-of-pocket costs.”

To help reduce his own costs, he told me he has put in place a high-deductible plan and was setting up health saving accounts that allow him to give a sum of money to each worker to use for their medical expenses.

As health insurance premiums continue to rise, more employers will likely heap more of those rising costs onto workers, many of whom will inevitably have a tough time paying for them.

Every time there has been a hint in the air that maybe, just maybe, America might embrace a universal system like peer nations across the globe that offer health care to all their citizens, the special interests—doctors, hospitals, insurers, employers, and others that benefit financially from the current system have snuffed out any possibility that might happen, worried that such a system could affect their profits.

For as long as I can remember, the public has been told America has the best health care system in the world. Major holes in our system exposed by The Commonwealth Fund belie that assumption.