Large, not-for-profit hospitals/health systems are getting a disproportionate share of unflattering attention these days. Last week was no exception: Here’s a smattering of their coverage:

Approximate Savings from Lowering Indiana Not-for-Profit Commercial Hospital Facility Prices to 260% of Medicare March 20, 2023 https://employersforumindiana.org/media/resources/Savings-from-Lowering-Indiana-Not-for-profit-Commercial-Hospital-Facility-Prices.

Jiang et al “Factors Associated with Hospital Commercial Negotiated Price for Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Brain” JAMA Network Open March 21. 2023;6(3):e233875. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.3875

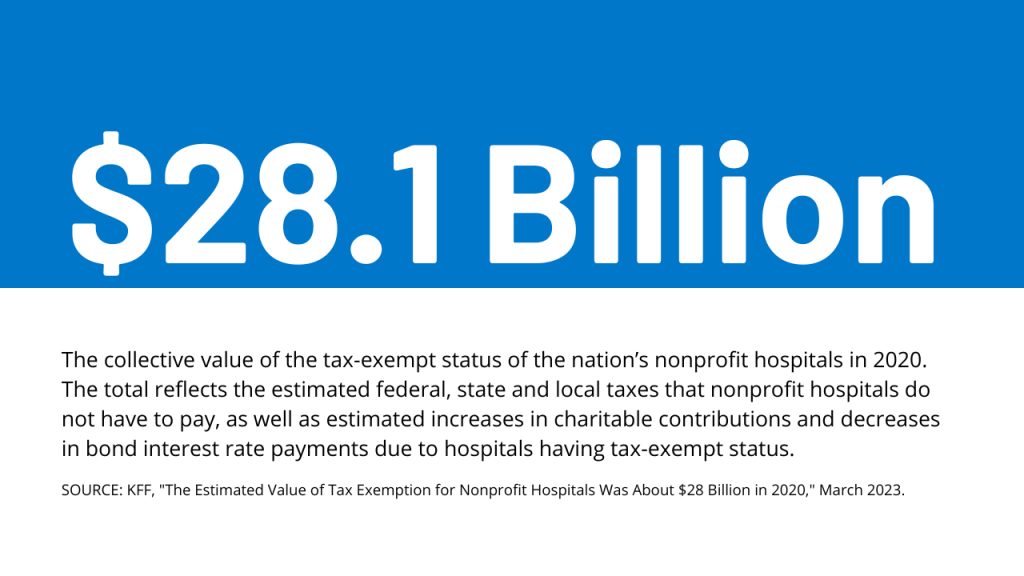

Not-for-profit benefits top charity care levels for hospitals: report Bond Buyer March 22, 2023 www.bondbuyer.com/news/not-for-profit-benefits-top-charity-care-levels-for-hospitals-report

What’s Behind Losses At Large Nonprofit Health Systems? Health Affairs March 24, 2023 www.healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/s-behind-losses-large-nonprofit-health-systems

Whaley et al What’s Behind Losses At Large Nonprofit Health Systems? Health Affairs March 24, 2023 10.1377/forefront.20230322.44474

A Pa. hospital’s revoked property tax exemption is a ‘warning shot’ to other nonprofits, expert says KYW Radio Philadelphia March 24, 2023 ww.msn.com/en-us/news/us/a-pa-hospital-s-revoked-property-tax-exemption-is-a-warning-shot-to-other-nonprofits-expert-says

These hospitals are ‘not for profit’ but very wealthy — should the state get more of their cash? News Sentinel March 26, 2023 www.news-sentinel.com/news/local-news/2019/09/26/kevin-leininger-these-hospitals-are-not-for-profit-but-very-wealthy-should-the-state-get-more-of-their-cash

These come on the heals of the Medicare Advisory Commission’s (MedPAC) March 2023 Report to Congress advising that all but safety-net hospitals are in reasonably good shape financially (contrary to industry assertions) and increased lawmaker scrutiny of “ill-gotten gains” in healthcare i.e., Moderna’s vaccine windfall, Medicare Advantage overpayments and employer activism about hospital price-gauging in several states.

Like every sector in healthcare, hospitals enter budget battles with good stories to tell about cost-reductions and progress in price transparency compliance. But in the current political and economic environment, large, not-for-profit hospitals and health systems seem to be targets of more adverse coverage than others as illustrated above. Like many NFP institutions in society (higher education, organized religion, government), erosion of trust is palpable. Not-for-profit hospitals and health systems are no exception.

The themes emerging from last week’s coverage are familiar:

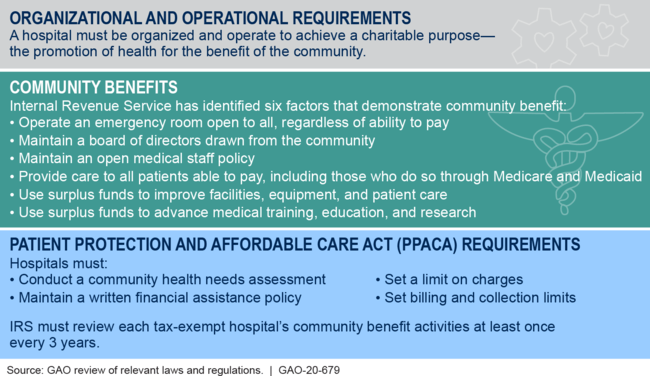

- ‘Not-for-profit hospitals/health systems, do not provide value commensurate with the tax exemptions they get.’

- ‘Not for profit hospitals & health systems take advantage of their markets and regulations to create strong brands and generate big profits.’.

- ‘Not for profit hospitals & health systems charge more than investor-owned hospitals: the victims are employers and consumers who pay higher-than-necessary prices for their services.’

- ‘NFP operators invest in risky ventures: when the capital market slumps, they are ill-prepared to manage. Risky investments, not workforce and supply chain issues, are the root causes of NFP financial stress. They’re misleading the public purposely.’

- ‘Executives in NFP systems are overpaid and patient collection policies are more aggressive than for-profits. NFP boards are ineffective.’

The stimulants for this negative attention are equally familiar:

- Proprietary studies by think tanks, trade associations, labor unions and consultancies designed to “prove a point” for/against not-for-profit hospitals/health systems.

- Government reports about hospital spending, waste, fraud, workforce issues, patient safety, concentration and compliance with transparency rules.

- Aggressive national/local reporting by journalists inclined to discount NFP messaging.

- Public opinion polls about declining trust in the system and growing concern about price transparency, affordability and equitable access.

- Politicians who use soundbites and dog whistles about NFP hospitals to draw attention to themselves.

The cumulative effect of these is confusion, frustration and distrust of not-for-profit hospitals and health systems. Most believe not-for-profit hospitals/health systems do not own the moral high ground they affirm to regulators and their communities (though religiously-affiliated systems have an edge). Most are unaware that more than half of all hospitals (54%) are not-for-profit and distinctions between safety net, rural, DSH, teaching and other forms of NFP ownership are non-specific to their performance.

What’s clear to the majority is that hospitals are expensive and essential. They’re soft targets representing 31.1% of the health system’s total spend ($4.3 trillion in 2021) increasing 4.9% annually in the last decade while inflation and GDP growth were less.

So why are not-for-profit systems bearing the brunt of hospital criticism?

Simply put: many NFP systems act more like Big Business than shepherds of community health. In fact, 4 of the top 10 multi-hospital system operators is investor owned: HCA (184), CHS (84), LifePoint (84), Tenet (65). In addition, 3 others are in the top 50: Ardent (30), UHS (26), Quorum (22). So, corporatization of hospital care using private capital and public markets for growth is firmly entrenched in the sector exposing not-for-profit operators to competition that’s better funded and more nimble. And, per industry studies, not-for-profits tend to stay in markets longer and operate unprofitable services more frequently than their investor-owned competitors. But does this matter to insurers, community leaders, legislators, employers, hospital employees and physicians? Some but not much.

My take:

There are no easy answers for not-for-profit hospitals/heath systems. The issue is about more than messaging and PR. It’s about more than Medicare reimbursement (7.5% below cost), protecting programs like 340B, keeping tax exemptions and maintaining barriers against physician-owned hospitals. The issue is NOT about operating income vs. investment income: in every business, both are essential and in each, economic cycles impact gains/losses. Each of these is important but only band-aids on an open wound in U.S. healthcare.

Near-term (the next 2 years), opportunities for not-for-profit hospitals involve administrative simplification to reduce costs and improve the efficiencies and effectiveness of the workforce. Clinical documentation using ChatGPT/Bard-like tools can have a massive positive impact—that’s just a start. Advocacy, public education and Board preparedness require bigger investments of time and resources. But that’s true for every hospital, regardless of ownership. These are table stakes to stay afloat.

The longer-term issue for NFPs is bigger:

It’s about defining the future of the U.S. health system in 2030 and beyond—the roles to be played and resources necessary for it to skate to where the puck is going. It’s about defining the role played by private employers and whether they’ll pay 220% more than Medicare pays to keep providers and insurers solvent. It’s about how underserved and unhealthy people are managed. It’s about defining systemness in healthcare and standardizing processes. It’s about defining sources of funding and optimal use of resources. Not-for-profit systems should drive these discussions in the communities they serve and at a national level.

MedPAC’s 17 member Commission will play a vital role, but equally important to this design process are inputs from employers, consumers and thought leaders who bring fresh insight. Until then, not-for-profit health systems will be soft targets for unflattering media because protecting the status quo is paramount to insiders who benefit from its dysfunction. Incrementalism defined as innovation is a recipe for failure.

It’s time to begin a discussion about the future of the U.S. health system—all of it, not just high-profile sectors like not-for-profit hospitals/health systems who are currently its soft target.