In a surprising turn of events, sources say that CVS Health is exploring the possibility of breaking up its business empire — a move that could unravel years of aggressive vertical integration, including its $70 billion acquisition of health insurer Aetna back in 2017.

While details are still slim, such a move signals just how dire the situation has become for CVSHealth as it navigates mounting financial and regulatory pressures on multiple fronts.

It’s yet another chapter in a story that has seen CVSHealth evolve from a retail pharmacy chain into a health care behemoth — but perhaps one that grew too big, too fast. And to be honest, I’m not surprised. I’ve seen this movie before. In fact, I saw it many times – although each time with different stars – during my 20 years in the health insurance business. One of the most memorable featured Aetna, which in the late 1990s and early 2000s had to retrench, at Wall Street’s insistence, after a buying spree of smaller health insurers that brought the company a ton of unprofitable accounts and disappointing bottom lines. Aetna followed its buying spree with a purging spree, dumping as many as eight million health plan enrollees in short order to get back into Wall Street’s good graces.

It seems that CVSHealth also bought too much too fast. The results? Rising expenses, frustrated patients, and now potential cracks in the corporate structure itself.

CVS: A Cautionary Tale of Vertical Integration

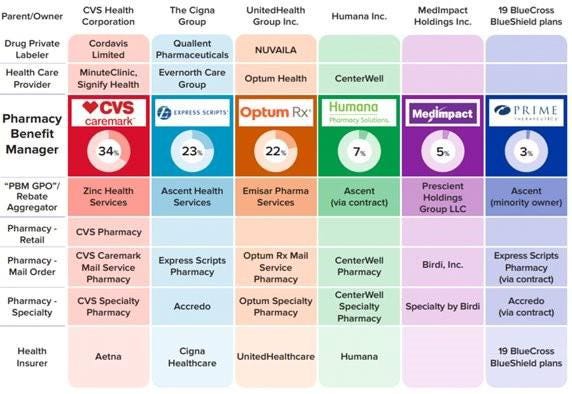

Large corporations like CVS and its peers have used their size to dominate various aspects of health care—whether it’s insurance, retail pharmacy, physician practices and clinics, and controlling the drug supply chain. But as these mega-corporations continue to grow, they also become harder to manage, and their inefficiencies start to become evident.

CVS’s acquisition of Aetna was hailed at the time as a strategic masterstroke — a way to streamline health care by bringing together the different parts of the system under one corporate umbrella. It was supposed to deliver “efficiencies” that would benefit both the company and patients.

But it’s not just the purchase of Aetna. From pharmacy benefit manager Caremark to Aetna to health care providers Signify Health and Oak Street Health — CVS’s business model has become increasingly complex, making it difficult to navigate regulatory scrutiny, rising costs and fierce competition in the retail pharmacy space.

The latest reports suggest that CVS’s board is trying to figure out where Caremark would land in the event of a breakup. Would it stay with the retail side or with the insurance arm?

This isn’t just an internal debate; it’s emblematic of the broader issue—CVS has built a vertically integrated structure that was supposed to work together to improve care, but investors are now questioning how and even if these pieces should fit together.

It’s Been a Hard Few Years for CVS

Federal Trade Commission’s Legal Action Against CVS’s Caremark and Other PBMs

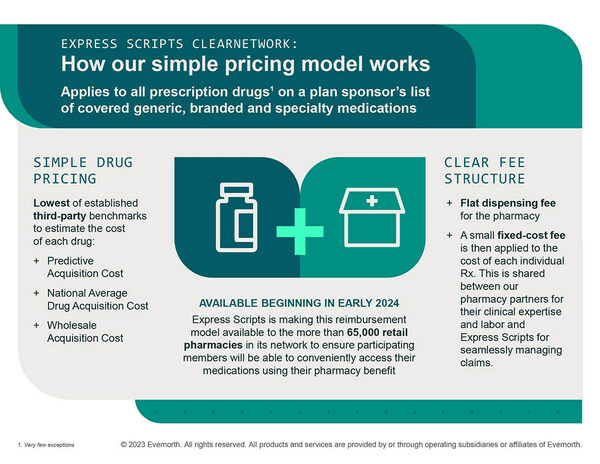

Instead, those supposed efficiencies have largely translated into higher costs for consumers and increased scrutiny from regulators, especially with CVS’s Caremark at the center of anti-competitive practices allegations by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). PBMs like Caremark control the drug pricing landscape in ways that lack transparency and disproportionately affect patients and independent pharmacies.

Now, as CVS grapples with rising medical costs within its Aetna business — just like its biggest competitors, UnitedHealth and Humana —the company’s management appears to be in damage control mode. While nothing is certain, discussions about splitting the business have reached the boardroom level, according to sources familiar with the matter. This comes as activist investors, like Glenview Capital, push for structural changes to improve CVS’s declining financial performance.

CVS’s Aetna Medicare Advantage Loss in New York City

New York City Mayor Eric Adams had a plan to force city municipal retirees out of traditional Medicare and into a corporate Aetna Medicare Advantage plan. The NYC Organization of Public Service Retirees vehemently opposed the move and spent months fighting it.

In August, a Manhattan Supreme Court judge permanently halted the mayor and Aetna’s attempts.

Wall Street Woes

For CVS Health, 2024 started off bad. CVS missed Wall Street financial analyst’s earnings-per-share expectations for the first quarter of 2024 by several cents. Shareholders’ furor sent CVS’ stock price tumbling from $67.71 to a 15-year low of $54 at one point.

An astonishing 65.7 million shares of CVS stock were traded that day. The company’s sin: paying too many claims for seniors and people with disabilities enrolled in its Medicare Advantage plans.

Also in August, CVS Health cut its 2024 forecast for a third time, citing troubles covering seniors via the company’s private Medicare Advantage business. Operating income for CVS Health’s insurance arm, Aetna, dropped a whopping 39% in Q3, which forced the company to shake up its leadership – moving CEO Karen Lynch into the role of managing insurance and publicly firing one of her lieutenants, Executive Vice President Brian Kane.

What’s Next?

The notion that CVS could split its operations would effectively unwind one of the most high-profile health care mergers in recent memory. A split up of the company would mark the end of an era in which health care conglomerates could grow unchecked. CVS’s struggle isn’t happening in isolation—other companies, like Walgreens and Rite Aid, are facing similar financial difficulties and structural questions.

CVS’s potential breakup could signal a broader industry trend toward unwinding massive, vertically integrated health care corporations.

Whether CVS breaks up or not, it’s clear that the model of health care mega-mergers, designed to consolidate power and increase corporate profits, is facing serious headwinds. Cigna recently announced that it is getting out of the Medicare Advantage business and Humana is getting out of the commercial insurance market. UnitedHealth, meanwhile, so far seems to be weathering those headwinds, but it, too, will be facing even more scrutiny by lawmakers and regulators in the months and years ahead.