https://mailchi.mp/66ebbc365116/the-weekly-gist-june-11-2021?e=d1e747d2d8

A number of the regional health systems we work with have either launched or are planning to launch their own Medicare Advantage (MA) plans. The good news is the breathless enthusiasm among hospitals for getting into the insurance business that followed the advent of risk-based contracting has been tempered in recent years.

Early strategies, circa 2012-15, involved health systems rushing into the commercial group and individual markets, only to run up against fierce competition from incumbent Blues plans, and an employer sales channel characterized by complicated relationships with insurance brokers.

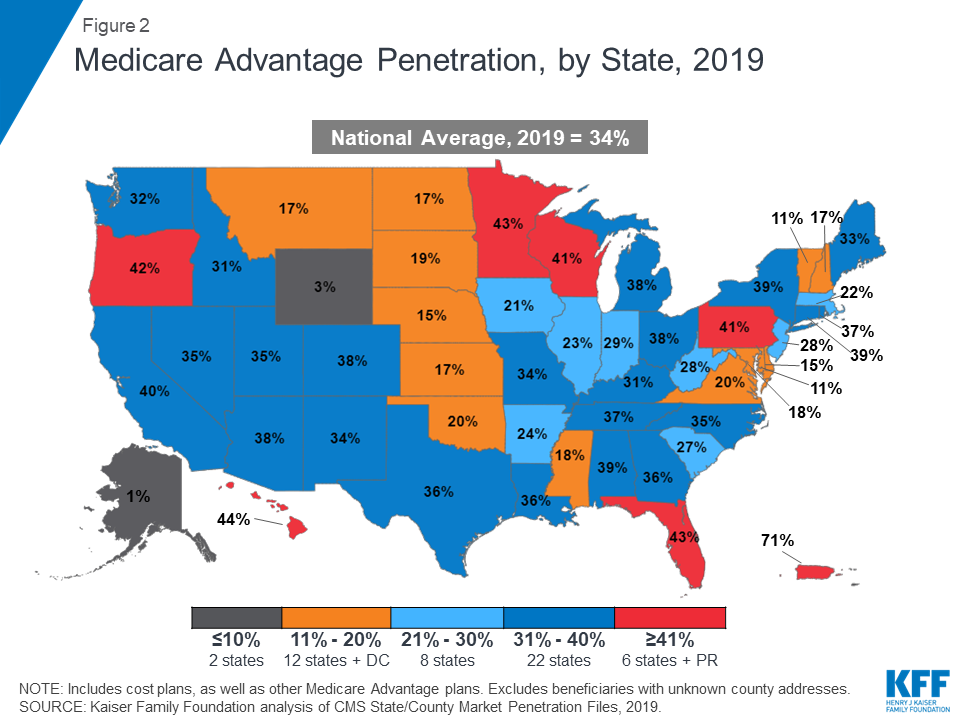

Slowly, a lightbulb has gone off among system strategists that MA is where the focus should be, given demographic and enrollment trends, and the fact that MA plans can be profitable with a smaller number of lives than commercial plans. It’s also a space that rewards investments in care management, as MA enrollees tend to be “sticky”, remaining with one plan for several years, which gives population health interventions a chance to reap benefits.

But as systems “skate to where the puck is going” with Medicare risk, they’re confronting a new challenge: slow growth. Selling a Medicare insurance plan is a “kitchen-table sale”, involving individual consumer purchase decisions, rather than a “wholesale sale” to a group market purchaser. That means that consumer marketing matters more—and the large national carriers are able to deploy huge advertising budgets to drive seniors toward their offerings.

Regional systems are often outmatched in this battle for MA lives, and we’re beginning to hear real frustration with the slow pace of growth among provider systems that have invested here. Patience will pay off, but so will scale, most likely—the bigger the system, the bigger the investment in marketing can be. (Although even large, national health systems are still dwarfed by the likes of UnitedHealthcare, CVS Health, and Humana.)

Look for the pursuit of MA lives to further accelerate the trend toward consolidation among regional health systems.