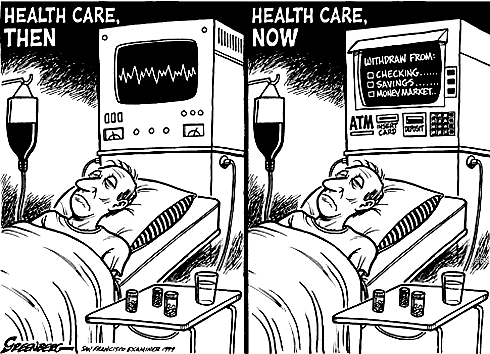

Not long ago, Dr. Richard Menger, a neurosurgeon, was ready to operate on a 16-year-old with complex scoliosis. A team of doctors had spent months preparing for the surgery, consulting orthopedists and cardiologists, even printing a 3D model of the teen’s spine.

The surgery was scheduled for a Friday when Menger got the news: the teen’s insurer, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama, had denied coverage of the surgery.

It wasn’t particularly surprising to Menger, who has been practicing in Alabama since 2019. Alabama essentially has one private insurer, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama, which has a whopping 94% of the market of large-group insurance plans, according to the health policy nonprofit KFF. That dominance allows the insurer to consistently deny claims, many doctors say, charge people more for coverage, and pay lower rates to doctors and hospitals than they would in other states.

“It makes the natural problems for insurance that much more magnified because there’s no market competition or choice,” says Menger, who in 2023 wrote an op-ed in 1819 News, a local news site, arguing that ending Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama’s health insurance monopoly would make people in the state healthier.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama also has the largest share of individual insurance plans in the state, according to data from the Centers for Medicaid & Medicare Services. Perhaps not coincidentally, Alabama also had the highest denial rates for in-network claims by insurers on the individual marketplace in 2023, according to a KFF analysis: 34%. Neighboring Mississippi, where the majority insurer has less of the market share at 81%, has an average denial rate of 15%.

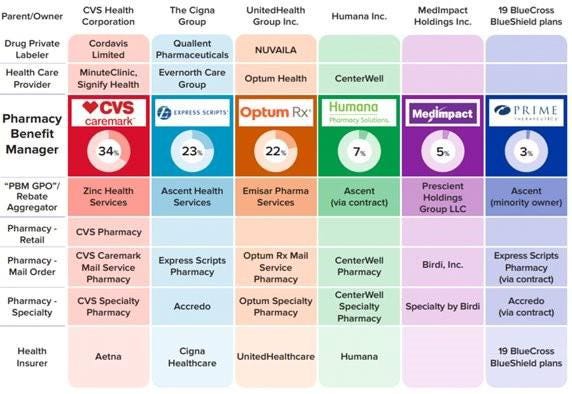

Alabama is an extreme case, but people in many other states face health insurance monopolies, too. One insurer, Premera Blue Cross Group, has a 94% share of the large-group market in Alaska, and Blue Cross Blue Shield of Wyoming has a 91% market share in that state. In 18 states, one insurer has 75% or more of the large-group health insurance marketplace, according to KFF data.

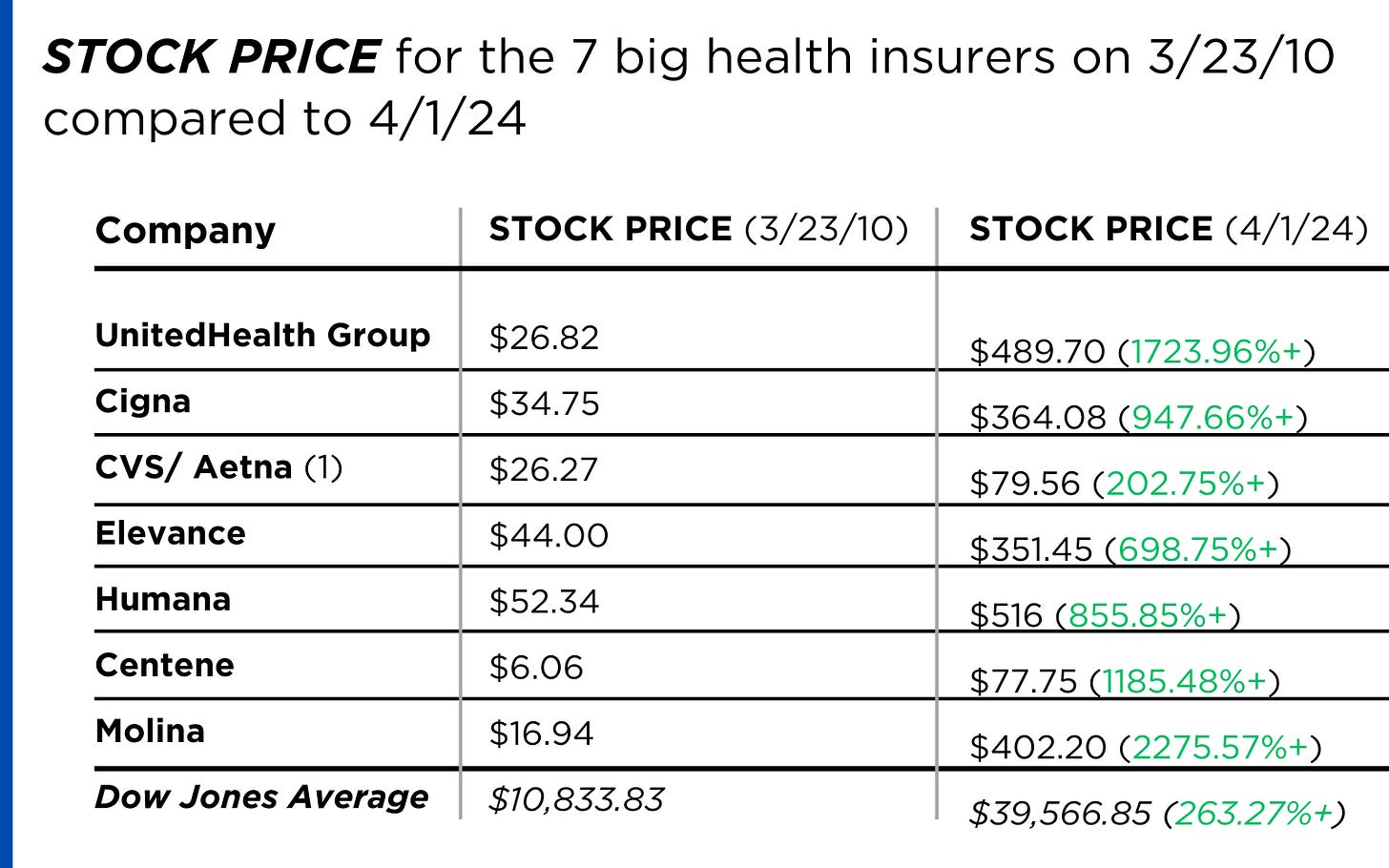

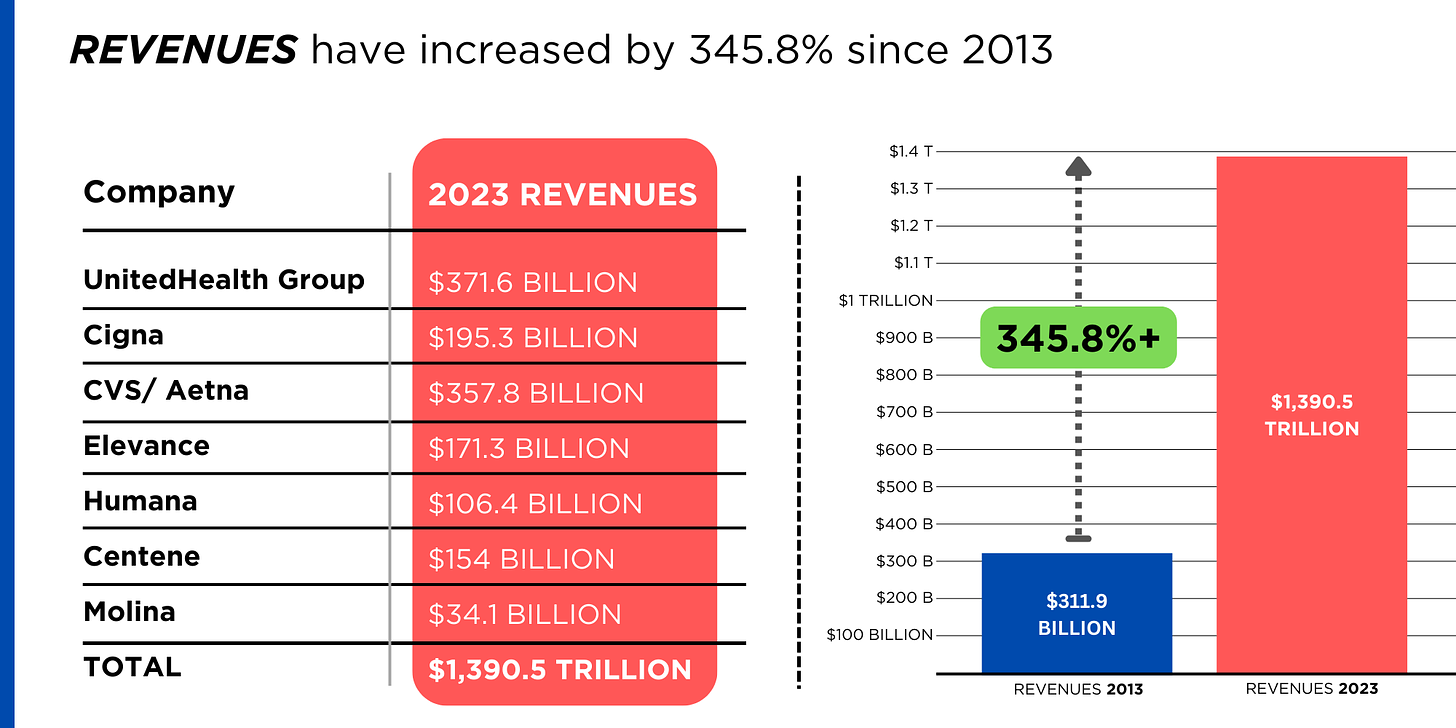

These monopolies drive up costs, says Leemore Dafny, a professor at Harvard Business School and Harvard Kennedy School who has long studied competition among health insurance companies and providers.

“More competitors tend to drive lower premiums and more generous benefits for consumers,” she says. “There’s a lot of concern from analysts like myself about concentration in a range of sectors, including health insurance.”

Bruce A. Scott, the immediate past president of the American Medical Association, has said that when the dominant insurer in his state of Kentucky was renegotiating its contract with his medical group, it offered lower rates than it had paid six years before. “This same type of financial squeeze play is found nationwide, and its frequency has been exacerbated by health insurance industry consolidation,” he wrote in The Hill in 2023.

What happened to competition? There used to be a lot more regional health insurers, Dafny says. But as costs started to rise, they didn’t have enough leverage to negotiate prices down with providers and stay profitable. As a result, many were happy to be acquired by larger companies. Then hospitals and doctor’s offices merged to get more leverage against the bigger insurers. Now, there’s a lot of concentration among both provider groups and insurers.

“None of this had anything to do with taking better care of patients,” she says. “It had to do with trying to get the upper hand.”

In a statement to TIME, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Alabama said that it was working to make the prior authorization process more transparent and reverse the requirement of prior authorization for certain in-network medical services. It will attempt to answer at least 80% of requests for prior authorization in near real-time by 2027, it says. (A coalition of major health insurers recently vowed to fix their prior authorization processes under pressure from the federal government.)

The insurer also says it welcomes competition. “We know Alabamians have a choice when it comes to choosing their health insurance carrier and we don’t take that for granted,” a spokesperson said in the statement. In the commercial and underwritten market—which represents the bulk of its business—Blue Cross Blue Shield Alabama competes with four other companies that sell individual, family, and group plans, the company says, and it competes with 68 companies who sell Medicare plans in Alabama. Its success in the state is partly because it sells policies in every county in Alabama, the insurer says, while others do not.

Other casualties of such a concentrated health-insurance marketplace are rural hospitals and providers. Small rural hospitals are often independent and have not merged with other systems like many of their large urban counterparts, so they have an even harder time negotiating with the one big insurer in the state, says Harold Miller, president and CEO of the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, a national policy center that studies health-care costs. That means big insurers will often refuse to cover procedures or pay lower prices for services.

“I’ve had rural hospitals tell me they can’t even get the health plan on the phone,” Miller says.

In the past decade, the Department of Justice has stopped some mergers, but has not been very aggressive at stopping consolidation in the health-care industry, Dafny says. That may be in part because the courts require a high standard of evidence to block a transaction, and the government might have been worried it would have lost whatever cases it brought.

A few factors prevent insurers with a monopoly from driving costs too high, says Benjamin Handel, an economics professor at the University of California, Berkeley who studies health care. One is a regulation called minimum loss ratio that essentially requires insurers to spend a certain share of what they earn from premiums on medical care. Another is that an insurer with a monopoly that angers consumers might attract attention from regulators, he says.

Of course, there’s not a whole lot regulators can do to make a marketplace more competitive. A state could try to incentivize more insurers to enter their states with tax breaks or other sweeteners, but it’s very hard to enter a market and offer low rates right away. The establishment of the health-care marketplaces in the Affordable Care Act allowed new entrants, Dafny says, but many of them did not survive.

Menger, the Alabama doctor, says that he and his colleagues—and therefore their patients—are basically stuck. His staff has to spend 10-15 hours a week negotiating with the insurer to get prior authorizations that sometimes don’t come, even while patients pay higher premiums.

The teenage boy eventually got approved for the scoliosis surgery, but not after the family went through a lot of stress with postponements and uncertainty. “I think it’s pretty clear that the more competition, the better things are,” Menger says. “This prior authorization nonsense is really hurting patients.”