https://healthcareuncovered.substack.com/p/inside-the-midyear-panic-at-unitedhealth

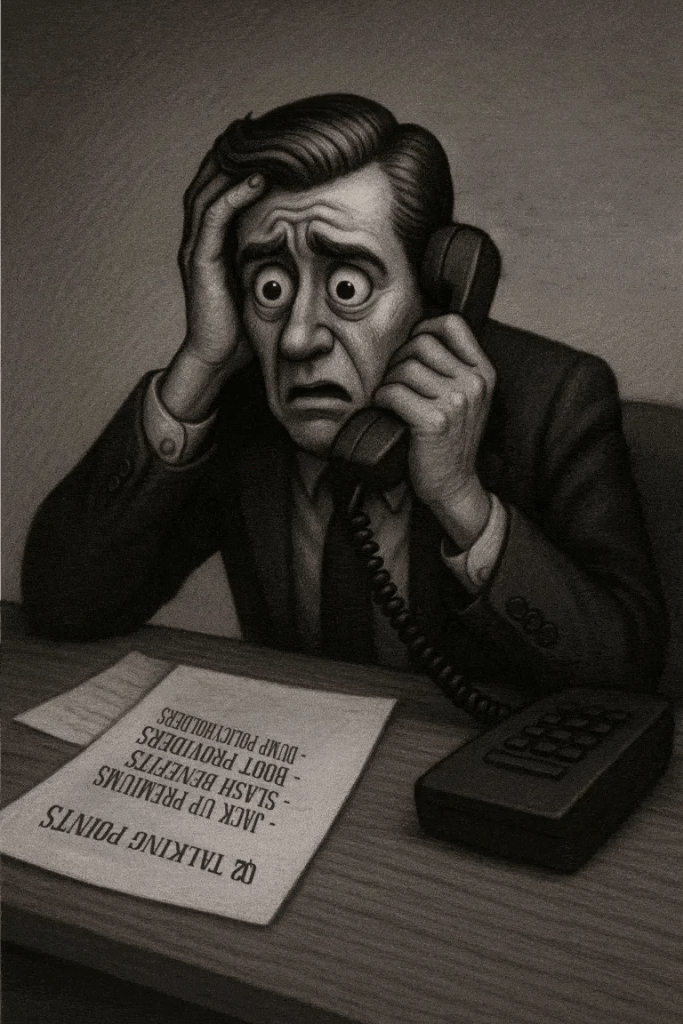

Imagine you’re facing your midyear performance review with your boss. You dread it, even though you’ve done all you thought possible and legal to help the company meet Wall Street’s profit expectations, because shareholders haven’t been pleased with your employer’s performance lately.

Now let’s imagine your employer is a health insurance conglomerate like, say, UnitedHealth Group. You’ve watched as the stock price has been sliding, sometimes a little and on some days crashing through lows not seen in years, like last Friday (down almost 5% in a single day, to $237.77, which is down a stunning 62% since a mid-November high of $630 and change).

You know what your boss is going to say. We all have to do more to meet the Street’s expectations. Something has changed from the days when the government and employers were overly generous, not questioning our value proposition, always willing to pick up the tab and pay many hidden tips, and we could pull our many levers to make it harder for people to get the care they need.

Despite government and media reports for years that the federal government has been overpaying Medicare Advantage plans like UnitedHealth’s – at least $84 billion this year alone – Congress has pretended not to notice. There is evidence that might be changing, with Republicans and Democrats alike making noises about cracking down on MA plans.

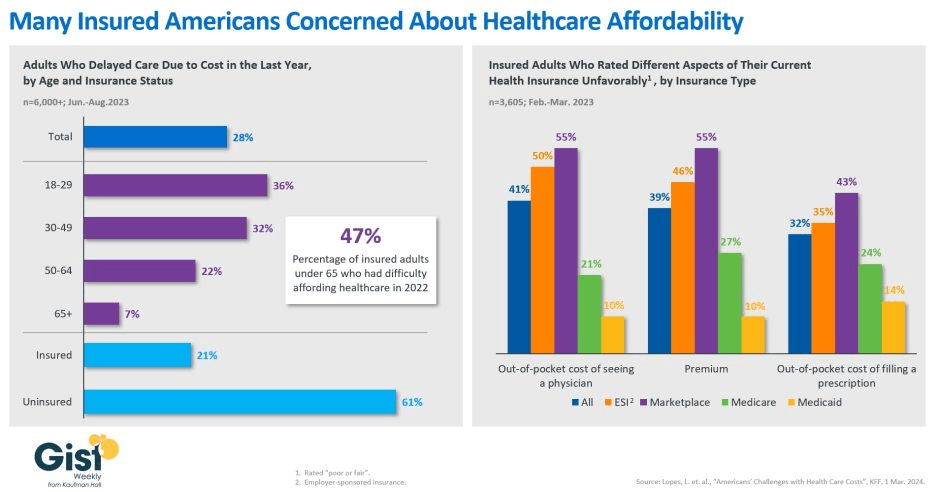

Employers have complained for ages about constantly rising premiums, but they’ve sucked it up, knowing they could pass much of the increase onto their workers – and make them pay thousands of dollars out of their own pockets before their coverage kicks in. Now, at least some of them are realizing they don’t have to work with the giant conglomerates anymore.

Doctors and hospitals have complained, too, about burdensome paperwork and not getting paid right and on time, but they’ve largely been ignored as the big conglomerates get bigger and are now even competing with them.

UnitedHealth is the biggest employer of doctors in the country. But doctors and hospitals are beginning to push back, too.

Since last fall, UnitedHealth and its smaller but still enormous competitors have found that “headwinds” are making it harder for them to maintain the profit margins investors demand. That is mainly because, despite the many barriers patients have to overcome to get the care they need, many of them are nevertheless using health care, often in the most expensive setting – the emergency room. They put off seeing a doctor so long because of insurers’ penny-wise-pound-foolishness that they had some kind of event that scared them enough to head straight to the ER.

It’s not just you who is dreading your midyear review. Everybody, regardless of their position on the corporate ladder, and even the poorly paid folks in customer service, are in the same boat. And so is your boss. Nobody will put the details of what has to be done in writing. They don’t have to. Your boss will remind you that you have to do your part to help the company achieve the “profitable growth” Wall Street demands, quarter after quarter after quarter. It never, ever ends. You know this because you and most other employees watch what happens after the company releases quarterly financials. You also watch your 401K balance and you see the financial consequences of a company that Wall Street isn’t happy with. And Wall Street is especially unhappy with UnitedHealth these days.

And when things are as bad as they are now at UnitedHealth’s headquarters in Minnesota, you know that a big consulting firm like McKinsey & Company has been called in, and that those suits will recommend some kind of “restructuring” and changes in leadership to get the ship back on course. You know the drill. Everybody already is subject to forced ranking, meaning that at the end of the year, some of your colleagues, regardless of job title, will fall below a line that means automatic termination. You pedal as fast as you can to stay above that line, often doing things you worry are not in the best interest of millions of people and might not even be lawful. But you know that if you have any chance of staying employed, much less getting a raise or bonus, you have to convince your superiors you are motivated and “engaged to win.” No one is safe. Look what happened to Sir Andrew Witty, whose departure as CEO to spend more time with his family (in London) was announced days after shareholders turned thumbs down on the company’s promises to return to an acceptable level of profitability.

If you are at UnitedHealth, you listened to what the once and again CEO, Stephen Hemsley, and CFO John Rex, who got shuffled to a lesser role of “advisor” to the CEO last week, laid out a new action plan to their bosses – big institutional investors who have been losing their shirts for months now. You know that what the C-Suite promised on their July 29 call will mean that you will have to “execute” to enable the company to deliver on those promises. And you know that you and your colleagues will have to inflict a lot more pain on everybody who is not a big shareholder – patients, taxpayers, employers, doctors, hospital administrators. That is your job. And you will try to do it because you have a mortgage, kids in college and maxed-out credit cards.

Here’s what Hemsley and his leadership team said, out loud in a public forum, although admittedly one that few people know about or can take an hour-and-a-half to listen to:

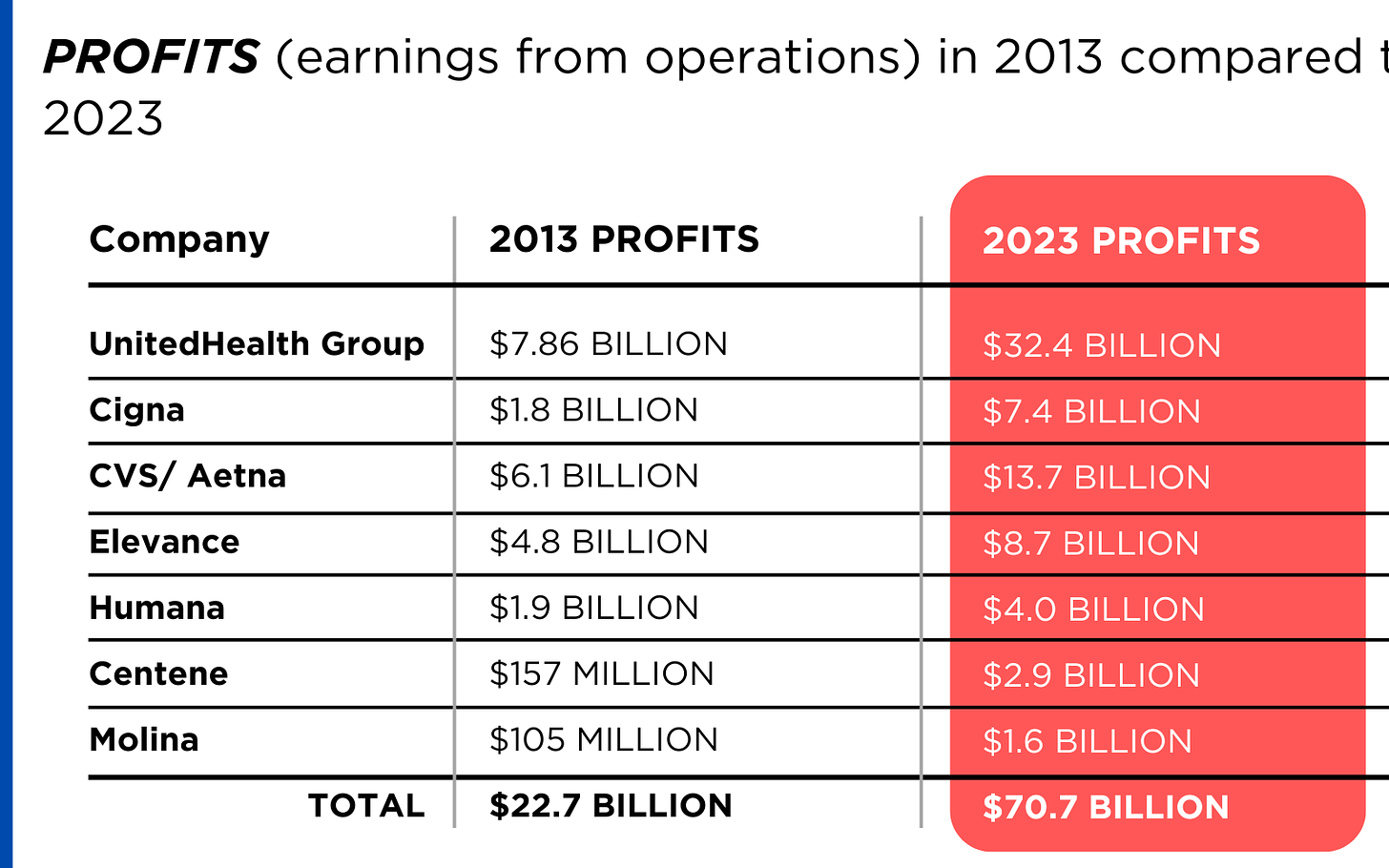

- Even though UnitedHealth took in billions more in revenue, its margins shrank a little because it had to pay more medical claims than expected.

- Still, the company made $14.3 billion in profits during the second quarter. That’s a lot but not as much as the $15.8 billion in 2Q 2024, and that made shareholders unhappy.

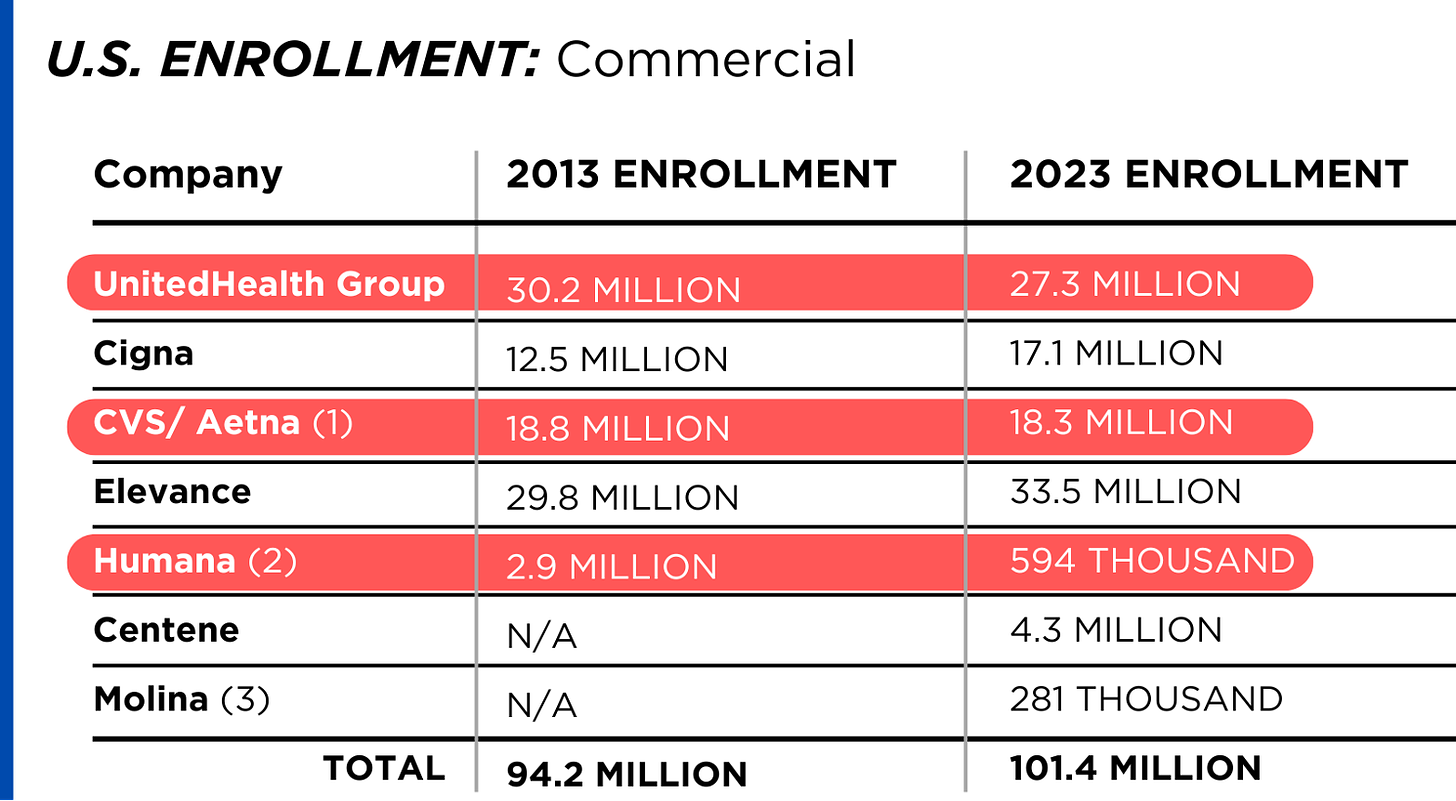

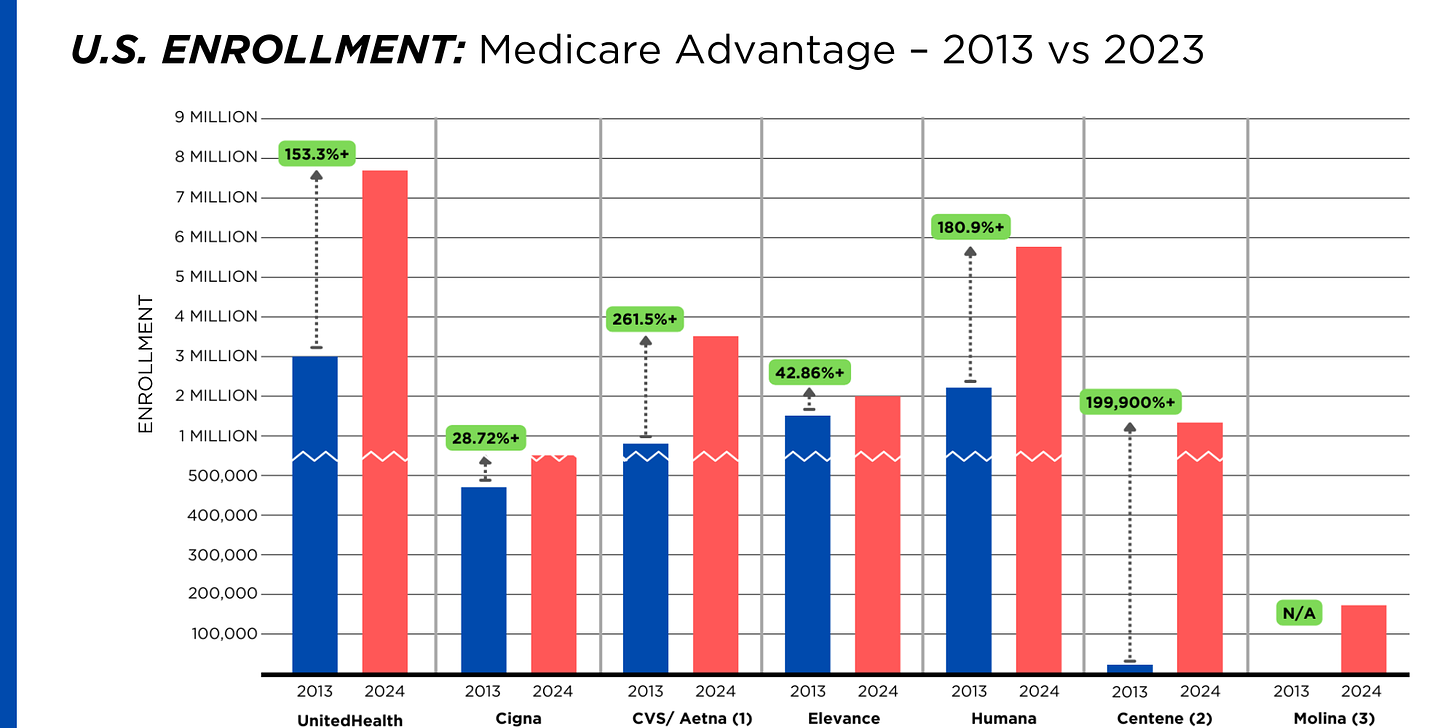

- Enrollment in its commercial (individual and employer) plans increased just 1%, but enrollment in its Medicare Advantage plans increased nearly 8%. That’s normally just fine, but something happened that the company’s beancounters couldn’t stop.

- Those seniors figured out how to get at least some care despite the company’s high barriers to care (aggressive use of prior authorization, “narrow” networks of providers, etc.)

To fix all of this, Hemsley and team promised:

- To dump 600,000 or so enrollees who might need care next year

- To raise premiums “in the double digits” – way above the “medical trend” that PriceWaterhouseCoopers predicts to be 8.5% (high but not double-digit high)

- Boot more providers it doesn’t already own out of network

- Reduce benefits

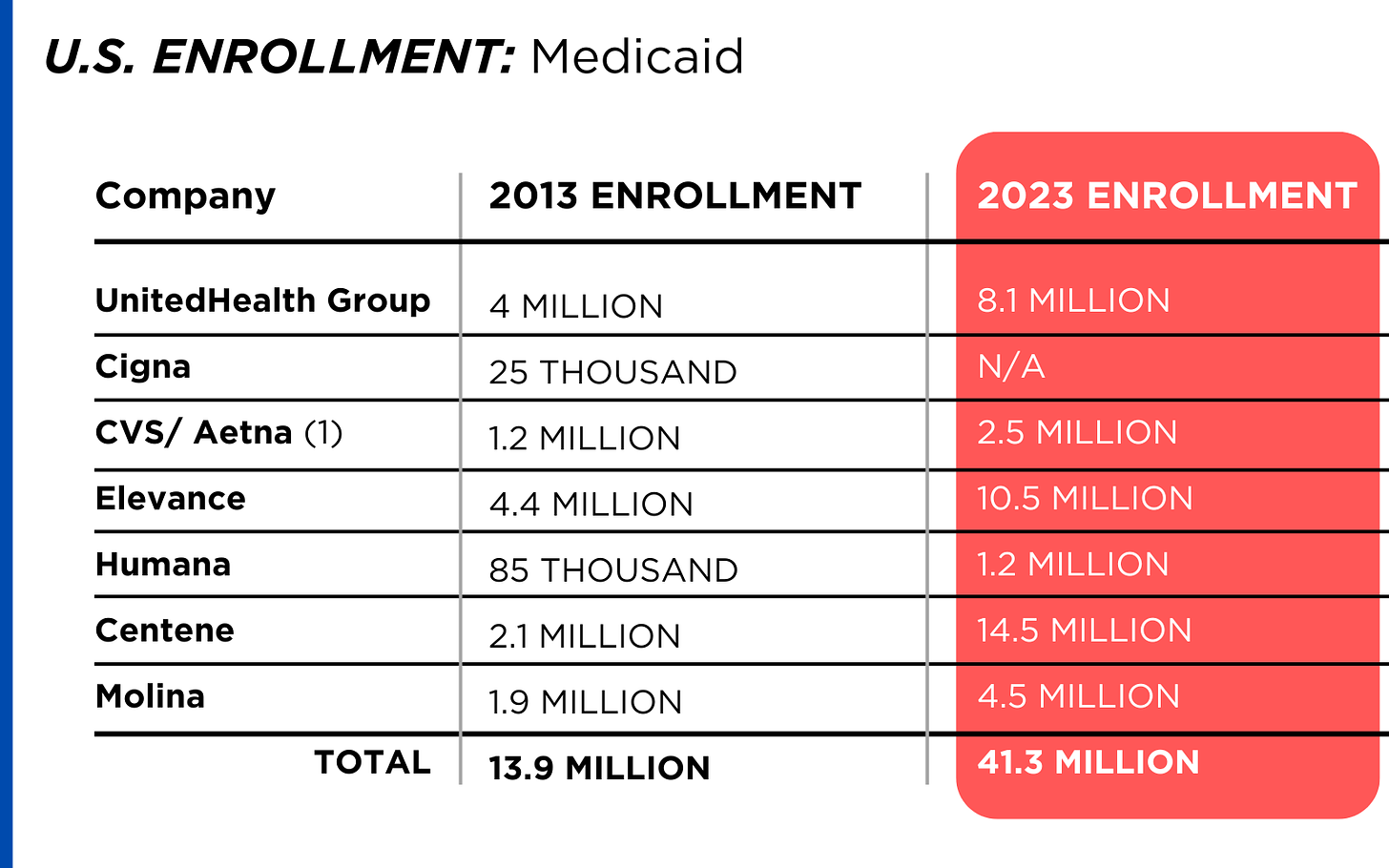

Throughout the call with investors (actually with a couple dozen Wall Street financial analysts, the only people who can ask questions), Hemsley and team went on and on about the “value-based care” the company theoretically delivers, without providing specifics. But here is what you need to know: If you are enrolled in a UnitedHealth plan of any nature – commercial, Medicare or Medicaid or VA (yes, VA, too) – expect the value of your coverage to diminish, just as it has year after year after year.

The term for this in industry jargon is “benefit buydown.”

That means that even as your premiums go up by double digits, you will soon have fewer providers to choose from, you likely will spend more out-of-pocket before your coverage kicks in, you might have to switch to a medication made by a drug company UnitedHealth will get bigger kickbacks from, and you might even be among the 600,000 policyholders who will get “purged” (another industry term) at the end of the year.

Why do we and our employers and Uncle Sam keep putting up with this?

Yes, we pay more for new cars and iPhones, but we at least can count on some improvements in gas mileage and battery life and maybe even better-placed cup holders. You can now buy a massive high-def TV for a fraction of what it cost a couple of years ago. Health insurance? Just the opposite.

As I will explain in a future post, all of the big for-profit insurers are facing those same headwinds UnitedHealth is facing. You will not be spared regardless of the name on your insurance card. If you still have one come January 1. Pain is on the way. Once again.