Last week was notable for healthcare because current events thrust it into the limelight…

Hospitals and emergency responders in Maine: Media attention to Gaza and the Speaker-less U.S. House of Representatives was temporarily suspended as the deaths of 18 in the U.S.’ 36h mass shooting in Lewiston, Maine took center stage. The immediate overload on Lewiston’s Central Maine Medical Center and Mass General where the 13 injured were treated (including 4 still hospitalized) drew media attention—largely gone by Friday when the shooter’s death by suicide was confirmed.

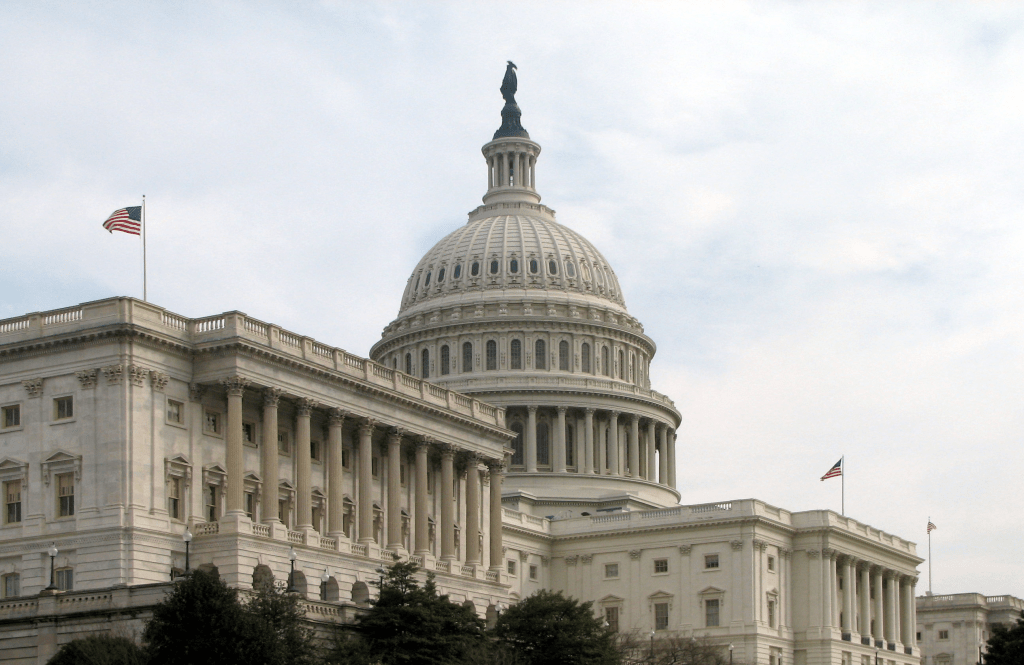

The New Speaker of the House: The GOP House of Representatives elected Mike Johnson, the 4-term Representative from Shreveport to the post vacant since October 3.

Johnson is no stranger to partisan positions on healthcare issues. As Chairman of the conservative-leaning Republican Steering Committee from 2019-2021, he led the group’s platform to dismantle the Affordable Care Act and supports a national restriction on abortions despite Senate GOP Leader McConnell’s preference it be left to states to decide.

With the prospect of a government shutdown November 17 due to inaction on the FY2024 federal budget, the 52-year-old lawyer faces delicate maneuvering around $106 billion proposed for Israel, the Ukraine, Taiwan and border security alongside appropriations for the health system that consumes 28% of entire federal outlays.

Health organizational business strategy announcements: Friction between physicians and hospital officials in Asheville (Mission) and Minnesota (Allina) attracted national coverage and brought attention to staffing, cultural and financial circumstances in these prominent organizations. —and on the heels of the Kaiser Permanente strike settlement. The divorce from Mass General by Dana Farber in Boston and announcements by GNC, Best Buy, Optum (re-branding NaviHealth) and Sanofi hit last week’s news cycle.

And indirectly, the 3Q 2023 GDP report by the Department of Commerce raised eyebrows: it was up 4.9%–far higher than expected prompting speculation that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will raise interest rates (again) at its meeting this week or next month. That means borrowing costs for struggling hospitals, nursing homes and consumers needing loans will go up along with household medical debt.

As news cycles go, this one was standard fare for healthcare: with the exception of business plan announcements by organizations or as elements of tragedies like Lewiston, Gaza or a pandemic,

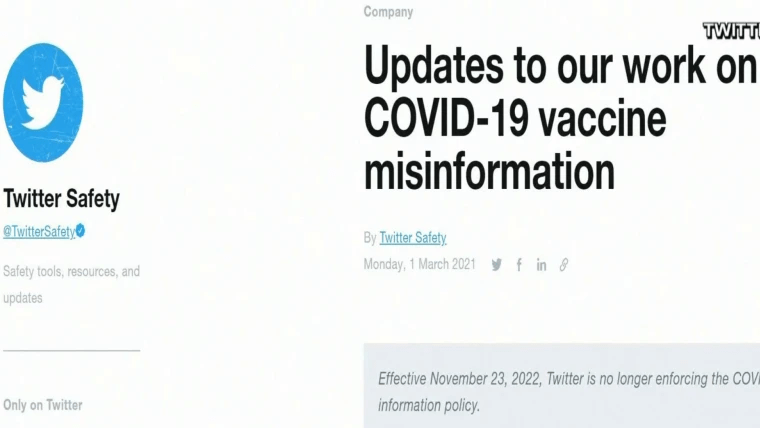

the business of the health system—how it operates is largely uncovered and often subject to misinformation or disinformation.

That’s the problem: it’s background noise to most voters who can be stoked to action over a single issue when prompted by special interests (i.e., Abortion rights, surprise billing, price transparency et al) but remain inattentive and marginally informed about the bigger role it plays in our communities and country and where it’s heading long-term.

The narrative common to most boils down to these:

- The U.S. health system is good, but it’s complicated. ‘How good’ depends on your insurance and your health—both are key.

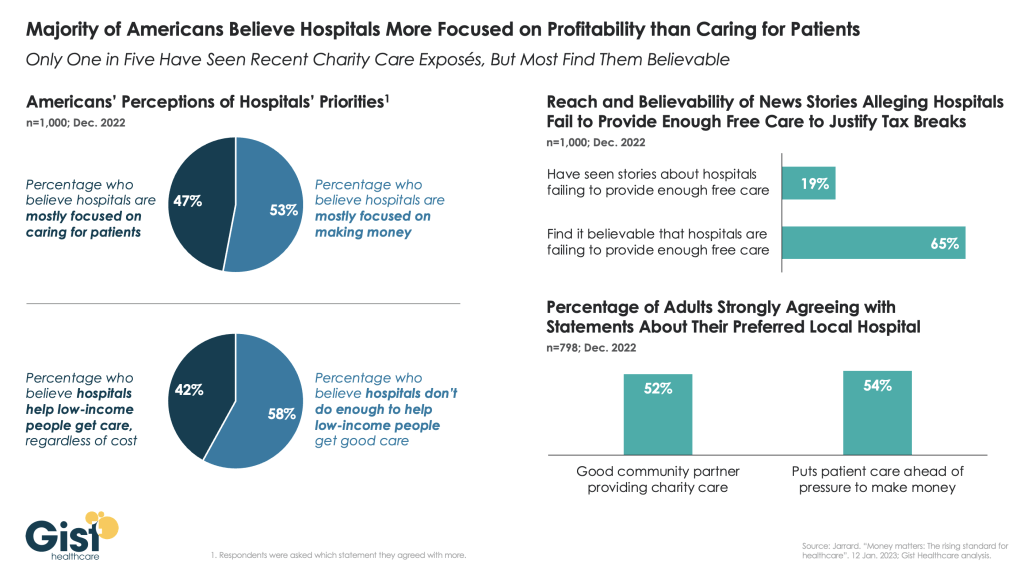

- The U.S. health system is expensive and profitable. It pays its executives well and its frontline workers unfairly.

- The delivery system focuses on the sick and injured; prevention and public health matter less.

- Hospitals and physicians are vital to the system; health insurers keep their costs down.

- The U.S. system pays lip service to “customer service” and ‘engaged consumers.” It is spin not supported by actions.

- The U.S. system needs to change dramatically.

In the next 3 weeks, attention will be on the federal budget: healthcare will be in the background unless temporarily an element of a mass tragedy. Each trade group will tout its accomplishments to regulators and pimp their advocacy punch list. Each company will gin-out news releases and commentary about the future of the system will default to think tanks and focused on a single issue of interest.

That’s the problem. In this era of social media, polarization, and mass transparency, these old ways of communicating no longer work. Left unattended, they undermine the value proposition on which the U.S. system is based.