With days before voters decide the composition of the 119th U.S. Congress and the next White House occupant, the immediate future for U.S. healthcare is both predictable and problematic:

It’s predictable that…

1-States will be the epicenter for healthcare legislation and regulation; federal initiatives will be substantially fewer.

At a federal level, new initiatives will be limited: continued attention to hospital and insurer consolidation, drug prices and the role of PBMs, Medicare Advantage business practices and a short-term fix to physician payments are likely but little more. The Affordable Care Act will be modified slightly to address marketplace coverage and subsidies and CMSs Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) will test new alternative payment models even as doubt about their value mounts. But “BIG FEDERAL LAWS” impacting the U.S. health system are unlikely.

But in states, activity will explode: for example…

- In this cycle, 10 states will decide their abortion policies joining 17 others that have already enacted new policies.

- 3 will vote on marijuana legalization joining 24 states that have passed laws.

- 24 states have already passed Prescription Drug Pricing legislation and 4 are considering commissions to set limits.

- 40 have expanded their Medicaid programs

- 35 states and Washington, D.C., operate CON programs; in 12 states, CONs have been repealed.

- 14 have legislation governing mental health access.

- 5 have passed or are developing commissions to control health costs.

- And so on.

Given partisan dysfunction in Congress and the surprising lack of attention to healthcare in Campaign 2024 (other than abortion coverage), the center of attention in 2025-2026 will be states. In addition to the list above, attention in states will address protections for artificial intelligence utilization, access to and pricing for weight loss medications, tax exemptions for not-for-profit health systems, telehealth access, conditions for private equity ownership in health services, constraints on contract pharmacies, implementation of site neutral payments, new 340B accountability requirements and much more. In many of these efforts, state legislatures and/or Governors will go beyond federal guidance setting the stage for court challenges, and the flavor of these efforts will align with a state’s partisan majorities: as of September 30th, 2024, Republicans controlled 54.85% of all state legislative seats nationally, while Democrats held 44.19%. Republicans held a majority in 56 chambers, and Democrats held the majority in 41 chambers. In 2024, 27 states are led by GOP governors and 23 by Dems and 11 face voters November 5. And going into the election, 22 states are considered red, 21 are considered blue and 7 are tagged as purple.

The U.S. Constitution affirms Federalism as the structure for U.S. governance: it pledges the pursuit of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” as its purpose but leaves the lion’s share of responsibilities to states to figure out how. Healthcare may be federalism’s greatest test.

2-Large employers will take direct action to control their health costs.

Per the Kaiser Family Foundation’s most recent employer survey, employer health costs are expected to increase 7% this year for the second year in a row. Willis Towers Watson, predicts a 6.4% increase this year on the heels of a 6% bump last year. The Business Group on Health, which represents large self-insured employers, forecasts an 8% increase in 2025 following a 7% increase last year. All well-above inflation, ages and consumer prices this year.

Employers know they pay 254% of Medicare rates (RAND) and they’re frustrated. They believe their concerns about costs, affordability and spending are not taken seriously by hospitals, physicians, insurers and drug companies. They see lackluster results from federal price transparency mandates and believe the CMS’ value agenda anchored by accountable care organizations are not achieving needed results. Small-and-midsize employers are dropping benefits altogether if they think they can. For large employers, it’s a different story. Keeping health benefits is necessary to attract and keep talent, but costs are increasingly prohibitive against macro-pressures of workforce availability, cybersecurity threats, heightened supply-chain and logistics regulatory scrutiny and shareholder activism.

Maintaining employee health benefits while absorbing hyper-inflationary drug prices, insurance premiums and hospital services is their challenge. The old playbook—cost sharing with employees, narrow networks of providers, onsite/near site primary care clinics et al—is not working to keep up with the industry’s propensity to drive higher prices through consolidation.

In 2025, they will carefully test a new playbook while mindful of inherent risks. They will use reference pricing, narrow specialty specific networks, technology-enabled self-care and employee gainsharing to address health costs head on while adjusting employee wages. Federal and state advocacy about Medicare and Medicaid funding, insurer and hospital consolidation and drug pricing will intensify. And some big names in corporate America will step into a national debate about healthcare affordability and accountability.

Employers are fed up with the status quo. They don’t buy the blame game between hospitals, insurers and drug companies. And they don’t think their voice has been heard.

3-Private equity and strategic investors will capitalize on healthcare market conditions.

The plans set forth by the two major party candidates feature populist themes including protections for women’s health and abortion services, maintenance/expansion of the Affordable Care Act and prescription drug price controls. But the substance of their plans focus on consumer prices and inflation: each promises new spending likely to add to the national deficit:

- Per the Non-Partisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, over the next 10 years, the Trump plan would add $7.5 trillion to the deficit; the Harris plan would add $3.5 trillion.

- Per the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, Harris’ proposals would add $1.2 trillion to the national deficits over 10 years and Trump’s proposals would add $5.8 trillion over the same period

Per the Congressional Budget Office, federal budget deficit for FY2024 which ended September 30 will be $1.8 trillion– $139 billion more than FT 2023. Revenues increased by an estimated $479 billion (or 11 percent). Revenues in all major categories, but notably individual income taxes, were greater than they were in fiscal year 2023. Outlays rose by an estimated $617 billion (or 10 percent). The largest increase in outlays was for education ($308 billion). Net outlays for interest on the public debt rose by $240 billion to total $950 billion.

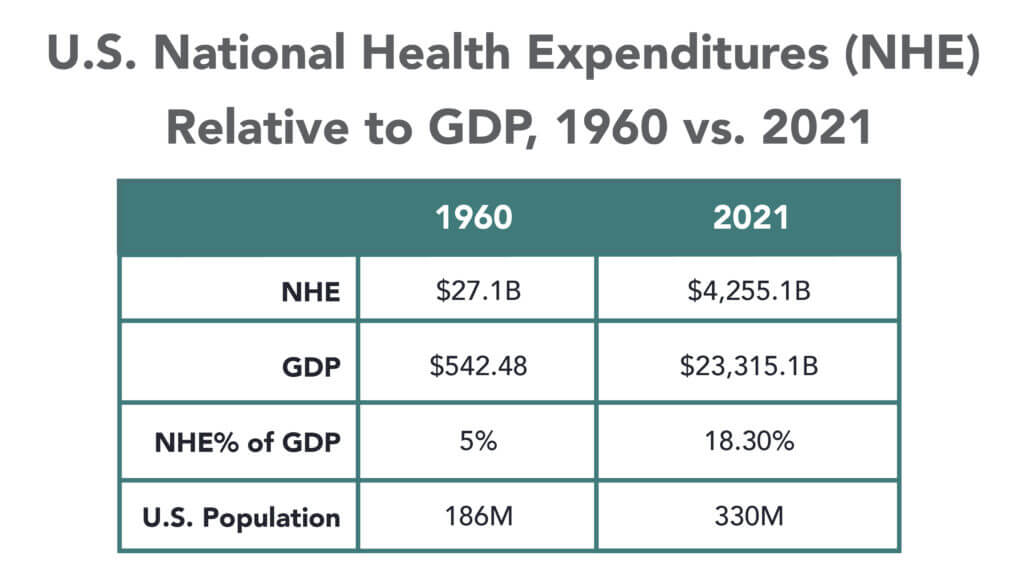

The federal government spent $6.75 trillion in 2024, a 10% increase from the prior year. Spending on Social Security (22% of total spending) and healthcare programs (28.5% of total spending) also increased substantially. The U.S. debt as of Friday was $37.77 trillion, or $106 thousand per citizen.

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports that federal debt held by the public averaged 48.3 % of GDP for the half century ending in 2023– far above its historic average. It projects next year’s national debt will hit 100% for the first time since the US military build-up in the second world war. And it forecast the debt reaching 122.4% in 2034 potentially pushing interest payments from 13% of total spending this year to 20% or more.

Adding debt is increasingly cumbersome for national lawmakers despite campaign promises, and healthcare is rivaled by education, climate and national defense in seeking funding through taxes and appropriations. Thus, opportunities for private investors in healthcare will increase dramatically in 2025 and 2026. After all, it’s a growth industry ripe for fresh solutions that improve affordability and cost reduction at scale.

Combined, these three predictions foretell a U.S. healthcare system that faces a significant pressure to demonstrate value.

They require every healthcare organization to assess long-term strategies in the likely context of reduced funding, increased regulation and heightened attention to prices and affordability. This is problematic for insiders accustomed to incrementalism that’s protected them from unwelcome changes for 3 decades.

Announcements last week by Walgreens and CVS about changes to their strategies going forward reflect the industry’s new normal: change is constant, success is not. In 2025, regardless of the election outcome, healthcare will be a major focus for lawmakers, regulators, employers and consumers.