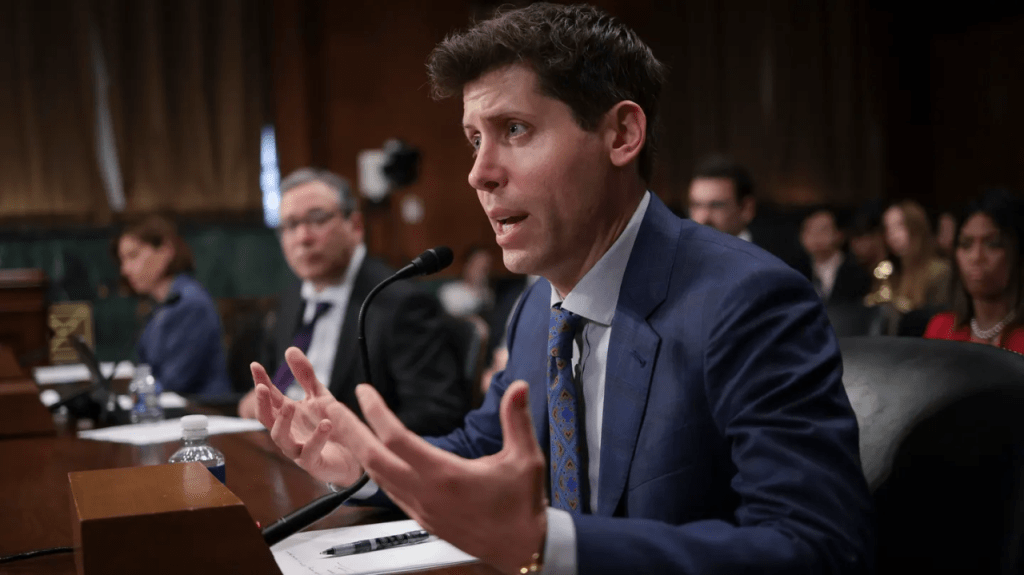

What a wild end to the year it was for Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI.

In the span of five white-knuckle days in November, the head of Silicon Valley’s most advanced generative AI company was fired by his board of directors, replaced by not one but two different candidates, hired to lead Microsoft’s AI-research efforts and, finally, rehired back into his CEO position at OpenAI with a new board.

A couple weeks later, TIME selected him “CEO of the Year.” Altman’s saga is more than a tale of tech-industry intrigue. His story provides three valuable lessons for not only aspiring and current healthcare leaders, but also everyone who works with and depends on them.

1. Agree On The Goal, Define It, Then Pursue It Tirelessly

OpenAI’s governance structure presented a unique case: a not-for-profit board, whose stated mission was to protect humanity, found itself overseeing an enterprise valued at more than $80 billion. Predictably, this setup invited conflict, as the company’s humanitarian mission began to clash with the commercial realities of a lucrative, for-profit entity.

But there’s little evidence the bruhaha resulted from Altman’s financial interests. According to IRS filings, the CEO’s salary was only $58,333 at the time of his firing, and he reportedly owns no stock.

While Altman clearly knows the company needs to raise money to fund the creation of ever-more-powerful AI tools, his primary goal doesn’t appear to revolve around maximizing shareholder value or his own wealth.

In fact, I believe Altman and the now-disbanded board shared a common mission: to save humanity. The problem was that the parties were 180 degrees apart when it came to defining how exactly to protect humanity.

Altman’s path to saving humanity involved racing forward as fast as possible. As CEO, he understands generative AI’s potential to radically enhance productivity and alleviate threats like world hunger and climate change.

By contrast, the board feared that breakneck AI development could spiral out of control, posing a threat to human existence. Rather than perceiving AGI (artificial general intelligence) as a savior, much of the board worried that a self-learning system might harm humanity.

This dichotomy pitted a CEO intent on changing the world against a board intent to progress at a cautious, incremental pace.

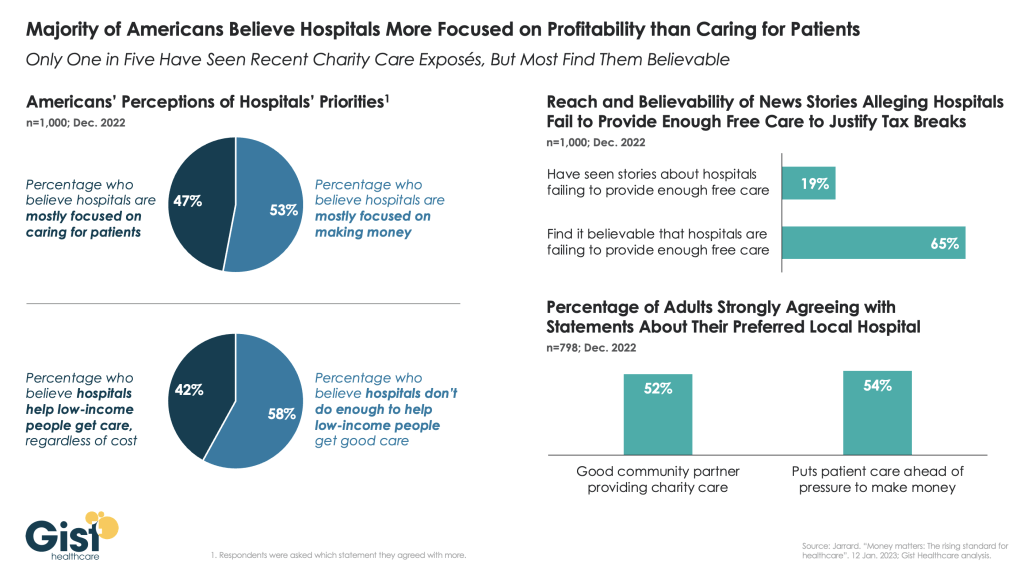

For Healthcare Leaders: Like OpenAI, American healthcare leaders share a common goal. Be they doctors, insurers or government health agencies, all tout the importance of “value-based care” (VBC), which in general terms, constitutes a financial and care-delivery model based on paying healthcare professionals for the quality of clinical outcomes they achieve rather than the quantity of services they provide. But despite agreeing on the target, leaders differ on what it means and how best to accomplish it. Some think of VBC as “pay for performance,” whereby doctors are paid small incentives based on metrics around prevention and patient satisfaction. These programs fail because clinicians ignore the metrics without incentives and total health suffers.

Other leaders believe VBC means paying insurers a set, annual, upfront fee to provide healthcare to a population of patients. This, too, fails since the insurers turn around and pay doctors and hospitals on a fee-for-service basis, and implement restrictive prior authorization requirements to keep costs down.

Instead of making minor financial tweaks that keep falling short of the goal, leaders who want to transform American medicine must play to win. This will require them to move quickly and completely away from fee-for-service payments (which rewards volume of care) to capitation at the delivery-system level (rewarding superior results by prepaying doctors and hospitals directly without insurers playing the part of middlemen).

Like OpenAI’s former board members, today’s healthcare leaders are playing “not to lose.” They avoid making big changes because they fear the backlash of risk-averse providers. But anything less than all in won’t make a dent given the magnitude of problems. To be effective, leaders must make hard decisions, accept the risks and be confident that once the changes are in place, no one will want to go back to the old ways of doing things.

2. Hire Visionary Leaders Who Inspire Boldly

Many tech-industry commentators have drawn comparisons between Altman and Steve Jobs. Both leaders possess(ed) the rare ability to foresee a better future and turn their visions into reality. And both demonstrate(d) passion for exceeding people’s wants and expectations—not for their own benefit but because they believe in a greater mission and purpose.

Altman and Jobs are what I call visionary leaders, who push their organizations and people to accomplish remarkable outcomes few could’ve believed possible. These types of leaders always challenge conservative boards.

When the OpenAI board realized it’s hard to constrain a CEO like Sam Altman, they fired him.

On day one of that decision, the board might have assumed their action would protect humanity and, therefore, earn the approval of OpenAI’s employees. But the story took a sharp turn when nearly all the company’s 770 workers signed a letter to the board in support of Altman, threatening to quit unless (a) their visionary leader was brought back immediately and (b) the board resigned.

Five days after the battle began, the board was facing a rebellion and had little choice but to back down.

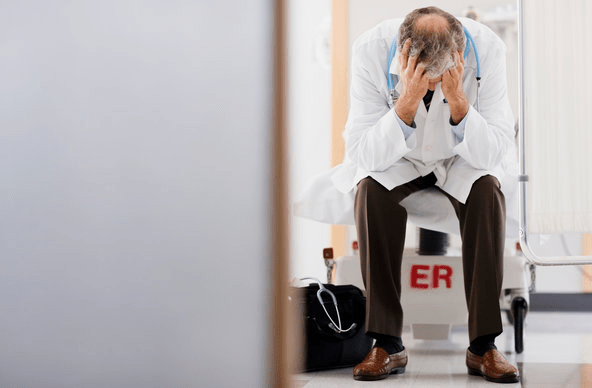

For Healthcare Leaders: The American healthcare system is struggling. Half of Americans say they can’t afford their out-of-pocket expenses, which max out at $16,000 for an insured family. American health is languishing with average life expectancy virtually unchanged since the start of this century. Maternal and infant mortality rates in the U.S. are double what they are in other wealthy nations. And inside medicine, burnout runs rampant. Last year, 71,000 physicians left the profession.

Visionary leadership, often sidelined in favor of the status quo, is crucial for transformative change. In healthcare, boards typically prioritize hiring CEOs with the ability to consolidate market control and achieve positive financial results rather than the ability to drive excellence in clinical outcomes. The consequence for both the providers and recipients of care proves painful.

Like OpenAI’s employees, healthcare professionals want leaders who are genuine, who have the courage to abandon bureaucratic safety in favor of innovative solutions, and who can ignite their passion for medicine. For a growing number of clinicians, the practice of medicine has become a job, not a mission. Without that spark, the future of medicine will remain bleak.

3. Embrace Transformative Technology

OpenAI’s board simultaneously promoted and feared ChatGPT’s potential. In this era of advanced technology, the dilemma of embracing versus restraining innovation is increasingly common.

The board could have shut down OpenAI or done everything in its power to advance the AI. It couldn’t, however, do both. When organizations in highly competitive industries try to strike a safe “balance,” choosing the less-contentious middle ground, they almost always fail to accomplish their goals.

For Healthcare Leaders: Despite being data-driven scientists, healthcare professionals often hesitate to embrace information technologies. Having been burned by tools like electronic healthcare records, which were designed to maximize revenue and not to facilitate medical care, their skepticism is understandable.

But generative AI is different because it has the potential to simultaneously increase quality, accessibility and affordability. This is where technology and skilled leadership must combine forces. It’s not enough for leaders to embrace generative AI. They must also inspire clinicians to apply it in ways that promote collaboration and achieve day-to-day operational efficiency and effectiveness. Without both, any other operational improvements will be incremental and clinical advances minimal at best.

If the boards of directors and other similar decision-making bodies in healthcare want their organizations to lead the process of change, they’ll need to select and support leaders with the vision, courage, and skill to take radical and risky leaps forward. If not, as OpenAI’s narrative demonstrates, they and their organizations will become insignificant and be left behind.