Hardly one month into 2021, the pressing priorities facing healthcare leaders are abundantly clear.

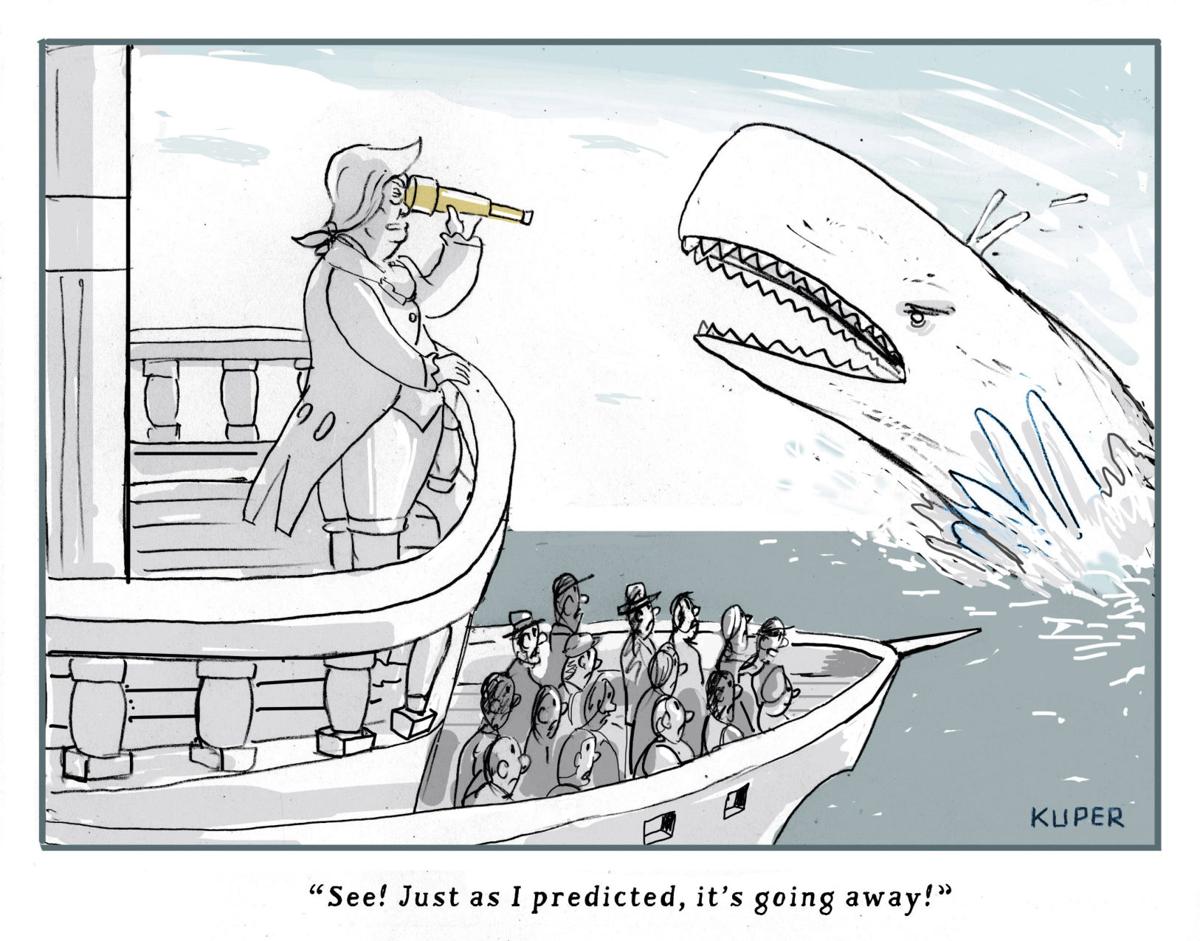

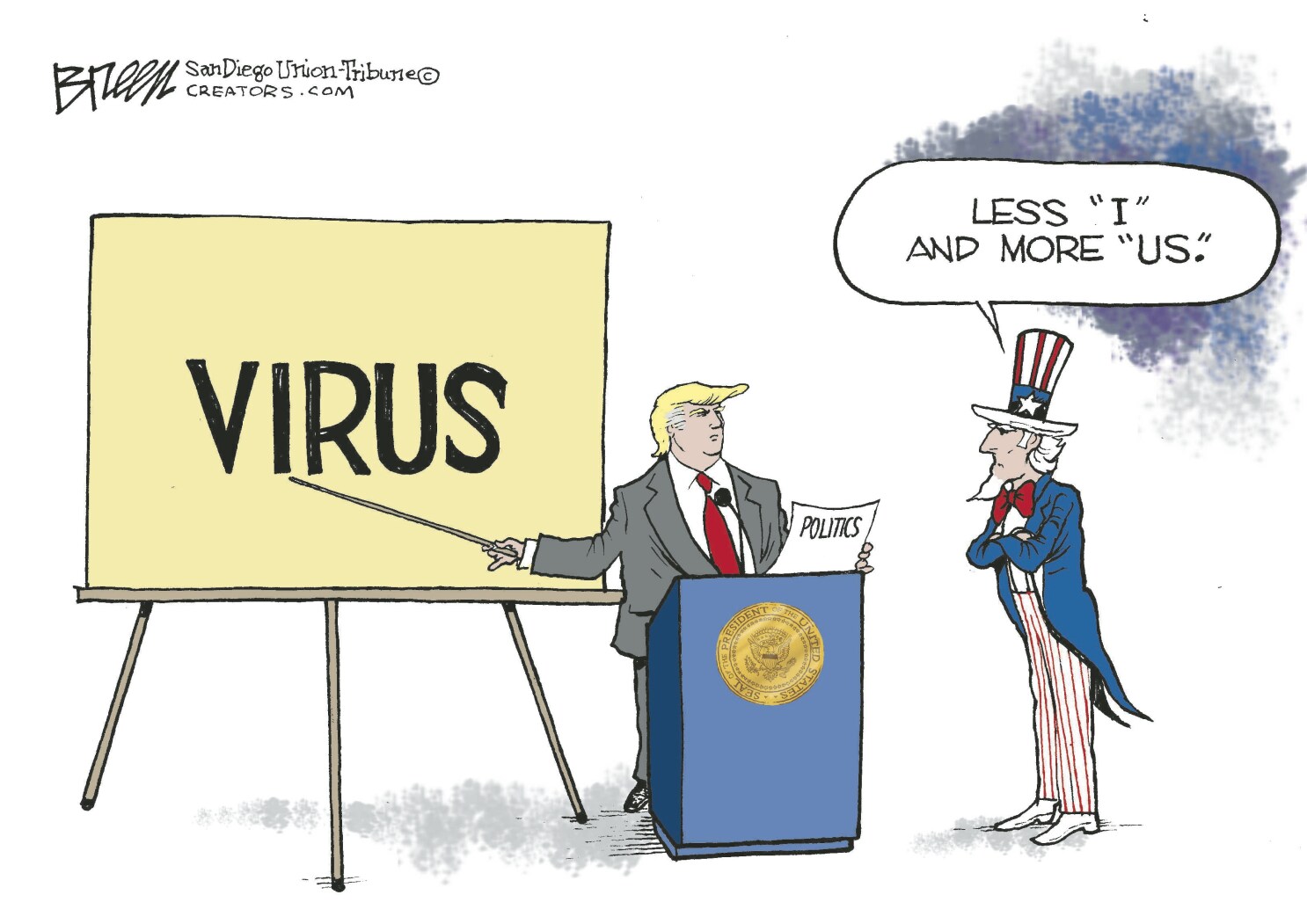

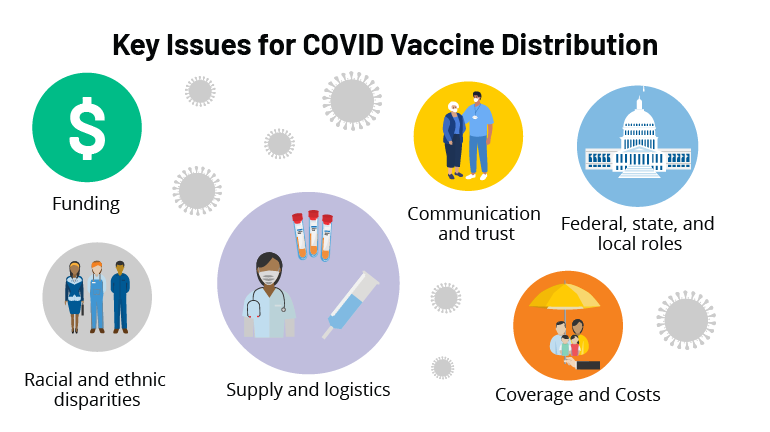

First, we will be living in a world preoccupied by COVID-19 and vaccination for many months to come. Remember: this is a marathon, not a sprint. And the stark reality is that the vaccination rollout will continue well into the summer, if not longer, while at the same time we continue to care for hundreds of thousands of Americans sickened by the virus. Despite the challenges we face now and in the coming months in treating the disease and vaccinating a U.S. population of 330 million, none of us should doubt that we will prevail. Despite the federal government’s missteps over the past year in managing and responding to this unprecedented public health crisis, historians will recognize the critical role of the nation’s healthcare community in enabling us to conquer this once-in-a-generation pandemic.

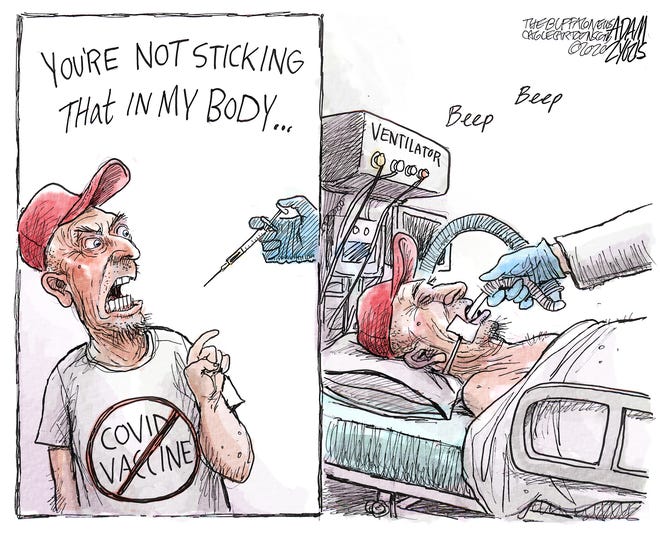

While there has been an overwhelming public demand for the vaccine during the past couple of weeks, there remains some skepticism within the communities we serve, including some of the most-vulnerable populations, so healthcare leaders will find themselves spending time and energy communicating the safety and efficacy of vaccines to those who may be hesitant. This is a good thing. It is our responsibility to share facts, further public education and influence public policy. COVID-19 has enhanced public trust in healthcare professionals, and we can maintain that trust if we keep our focus on the right things — namely, how we improve the health of our communities.

And as healthcare leaders diligently balance this work, we also have a great opportunity to reimagine what our hospitals and health systems can be as we emerge from the most trying year of our professional lifetimes. How do you want your hospital or system organized? What kind of structural changes are needed to achieve the desired results? What do you really want to focus on? Amid the pressing priorities and urgent decision-making needed to survive, it is easy to overlook the great reimagination period in front of us. The key is to forget what we were like before COVID-19 and reflect upon what we want to be after.

These changes won’t occur overnight. We’ll need patience, but here are my thoughts on five key questions we need to answer to get the right results.

1. How do you enhance productivity and become more efficient? Throughout 2021, most systems will be in recovery mode from COVID’s financial bruises. Hospitals saw double-digit declines in inpatient and outpatient volumes in 2020, and total losses for hospitals and health systems nationwide were estimated to total at least $323 billion. While federal relief offset some of our losses, most of us still took a major financial hit. As we move forward, we must reorganize to operate as efficiently as possible. Does reorganization sound daunting? If so, remember the amount of reorganization we mustered to work effectively in the early days of the pandemic. When faced with no alternative, healthcare moved heaven and earth to fulfill its mission. Crises bring with them great clarity. It’s up to leaders to keep that clarity as this tragic, exhausting and frustrating crisis gradually fades.

2. How do you accelerate digital care? COVID-19 changed our relationship with technology, personally and professionally. Look at what we accomplished and how connected we remain. We were reminded of how high-quality healthcare can go unhindered by distance, commutes and travel constraints with the right technology and telehealth programs in place. Health system leaders must decide how much of their business can be accommodated through virtual care so their organizations can best offer convenience while increasing access. Oftentimes, these conversations don’t get far before confronting doubts about reimbursement. Remember, policy change must happen before reimbursement catches up. If you wait for reimbursement before implementing progressive telehealth initiatives, you’ll fall behind.

3. How will your organization confront healthcare inequities? In 2020, I pledged that Northwell would redouble its efforts and remain a leader in diversity and inclusion. I am taking this commitment further this year and, with the strength of our diverse workforce, will address healthcare inequities in our surrounding communities head-on. This requires new partnerships, operational changes and renewed commitments from our workforce. We need to look upstream and strengthen our reach into communities that have disparate access to healthcare, education and resources. We must push harder to transcend language barriers, and we need our physicians and medical professionals of color reinforcing key healthcare messages to the diverse communities we serve. COVID-19’s devastating effect on communities of color laid bare long-standing healthcare inequalities. They are no longer an ugly backdrop of American healthcare, but the central plot point that we can change. If more equitable healthcare is not a top priority, you may want to reconsider your mission. We need leaders whose vision, commitment and courage match this moment and the unmistakable challenge in front of us.

4. How will you accommodate the growing portion of your workforce that will be remote? Ten to 15 percent of Northwell’s workforce will continue to work remotely this year. In the past, some managers may have correlated remote work and teams with a decline in productivity. The past year defied that assumption. Leaders now face decisions about what groups can function remotely, what groups must return on-site, and how those who continue to work from afar are overseen and managed. These decisions will affect your organizations’ culture, communications, real estate strategy and more.

5. How do you vigorously hold onto your cultural values amid all of this change? This will remain a test through 2021 and beyond. Culture is the personality of your organization. Like many health systems and hospitals, much of Northwell’s culture of connectedness, awareness, respect and empathy was built through face-to-face interaction and relationships where we continually reinforced the organization’s mission, vision and values. With so many employees now working remotely, how can we continue to bring out the best in all of our people? We will work to answer that question every day. The work you put in to restore, strengthen and revitalize your culture this year will go a long way toward cementing how your employees, patients and community come to see your organization for years to come. Don’t underestimate the power of these seemingly simple decisions.

While we’ve been through hell and back over the past year, I’m convinced that the healthcare community can continue to strengthen the public trust and admiration we’ve built during this pandemic. However, as we slowly round the corner on COVID-19, our future success will hinge on what we as healthcare organizations do now to confront the questions above and others head-on. It won’t be quick or easy and progress will be a jagged line. Let’s resist the temptation to return to what healthcare was and instead work toward building what healthcare can be. After the crisis of a lifetime, here’s our opportunity of a lifetime. We can all be part of it.