Cartoon – Do you dwell on…

“I can give you an argument, but I can’t give you an understanding.”

Samuel Johnson

https://www.yahoo.com/news/next-big-covid-variant-could-100250868.html

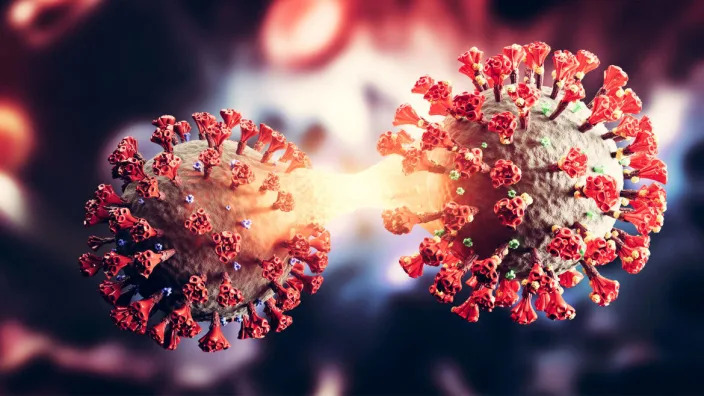

Even as daily new COVID cases set all-time records and hospitals fill up, epidemiologists have arrived at a perhaps surprising consensus. Yes, the latest Omicron variant of the novel coronavirus is bad. But it could have been a lot worse.

Even as cases have surged, deaths haven’t—at least not to the same degree. Omicron is highly transmissible but generally not as severe as some older variants—“lineages” is the scientific term.

We got lucky. But that luck might not hold. Many of the same epidemiologists who have breathed a sigh of relief over Omicron’s relatively low death rate are anticipating that the next lineage might be much worse.

The New Version of the Omicron Variant Is a Sneaky Little Bastard

Fretting over a possible future lineage that combines Omicron’s extreme transmissibility with the severity of, say, the previous Delta lineage, experts are beginning to embrace a new public health strategy that’s getting an early test run in Israel: a four-shot regimen of messenger-RNA vaccine.

“I think this will be the strategy going forward,” Edwin Michael, an epidemiologist at the Center for Global Health Infectious Disease Research at the University of South Florida, told The Daily Beast.

Omicron raised alarms in health agencies all over the world in late November after officials in South Africa reported the first cases. Compared to older lineages, Omicron features around 50 key mutations, some 30 of which are on the spike protein that helps the virus to grab onto our cells.

Some of the mutations are associated with a virus’s ability to dodge antibodies and thus partially evade vaccines. Others are associated with higher transmissibility. The lineage’s genetic makeup pointed to a huge spike in infections in the unvaccinated as well as an increase in milder “breakthrough” infections in the vaccinated.

That’s exactly what happened. Health officials registered more than 10 million new COVID cases the first week of January. That’s nearly double the previous worst week for new infections, back in May. Around 3 million of those infections were in the United States, where Omicron coincided with the Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year holidays and associated traveling and family gatherings.

But mercifully, deaths haven’t increased as much as cases have. Worldwide, there were 43,000 COVID deaths the first week of January—fewer than 10,000 of them in the U.S. While deaths tend to lag infections by a couple weeks, Omicron has been dominant long enough that it’s increasingly evident there’s been what statisticians call a “decoupling” of cases and fatalities.

“We can say we dodged a bullet in that Omicron does not appear to cause as serious of a disease,” Stephanie James, the head of a COVID testing lab at Regis University in Colorado, told The Daily Beast. She stressed that data is still being gathered, so we can’t be certain yet that the apparent decoupling is real.

Assuming the decoupling is happening, experts attribute it to two factors. First, Omicron tends to infect the throat without necessarily descending to the lungs, where the potential for lasting or fatal damage is much, much higher. Second, by now, countries have administered nearly 9.3 billion doses of vaccine—enough for a majority of the world’s population to have received at least one dose.

Omicron Shows the Unvaccinated Will Never Be Safe

In the United States, 73 percent of people have gotten at least one dose. Sixty-two percent have gotten two doses of the best mRNA vaccines. A third have received a booster dose.

Yes, Omicron has some ability to evade antibodies, meaning the vaccines are somewhat less effective against this lineage than they are against Delta and other older lineages. But even when a vaccine doesn’t prevent an infection, it usually greatly reduces its severity.

For many vaccinated people who’ve caught Omicron, the resulting COVID infection is mild. “A common cold or some sniffles in a fully vaxxed and boosted healthy individual,” is how Eric Bortz, a University of Alaska-Anchorage virologist and public health expert, described it to The Daily Beast.

All that is to say, Omicron could have been a lot worse. Viruses evolve to survive. That can mean greater transmissibility, antibody-evasion or more serious infection. Omicron mutated for the former two. There’s a chance some future Sigma or Upsilon lineage could do all three.

When it comes to viral mutations, “extreme events can occur at a non-negligible rate, or probability, and can lead to large consequences,” Michael said. Imagine a lineage that’s as transmissible as Omicron but also attacks the lungs like Delta tends to do. Now imagine that this hypothetical lineage is even more adept than Omicron at evading the vaccines.

2022’s Hottest New Illness: Flurona

That would be the nightmare lineage. And it’s entirely conceivable it’s in our future. There are enough vaccine holdouts, such as the roughly 50 million Americans who say they’ll never get jabbed, that the SARS-CoV-2 pathogen should have ample opportunities for mutation.

“As long as we have unvaccinated people in this country—and across the globe—there is the potential for new and possibly more concerning viral variants to arise,” Aimee Bernard, a University of Colorado immunologist, told The Daily Beast.

Worse, this ongoing viral evolution is happening against a backdrop of waning immunity. Antibodies, whether vaccine-induced or naturally occurring from past infection, fade over time. It’s not for no reason that health agencies in many countries urge booster doses just three months after initial vaccination. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is an outlier, and recommends people get boosted after five months.

A lineage much worse than Omicron could evolve at the same time that antibodies wane in billions of people all over the world. That’s why many experts believe the COVID vaccines will end up being annual or even semi-annual jabs. You’ll need a fourth jab, a fifth jab, a sixth jab, et cetera, forever.

Israel, a world leader in global health, is already turning that expectation into policy. Citing multiple studies that showed a big boost in antibodies with an additional dose of mRNA and no safety concerns, the country’s health ministry this week began offering a fourth dose to anyone over the age of 60, who tend to be more vulnerable to COVID than younger people.

That should be the standard everywhere, Ali Mokdad, a professor of health metrics sciences at the University of Washington Institute for Health, told The Daily Beast. “Scientifically, they’re right,” he said of the Israeli health officials.

If there’s a downside, it’s that there are still a few poorer countries—in Africa, mostly—where many people still struggle to get access to any vaccine, let alone boosters and fourth doses. If and when other richer countries follow Israel’s lead and begin offering additional jabs, there’s some risk of even greater inequity in global vaccine distribution.

“The downside is for the rest of the world,” Mokdad said. “I’m waiting to get my first dose and you guys are getting a fourth?”

The solution isn’t to deprive people of the doses they need to maintain their protection against future—and potentially more dangerous—lineages. The solution, for vaccine-producing countries, is to further boost production and double down on efforts to push vaccines out to the least privileged communities.

A sense of urgency is key. For all its rapid spread, Omicron has actually gone fairly easy on us. Sigma or Upsilon might not.

Over the past two years, historians and analysts have compared the coronavirus to the 1918 flu pandemic. Many of the mitigation practices used to combat the spread of the coronavirus, especially before the development of the vaccines, have been the same as those used in 1918 and 1919 — masks and hygiene, social distancing, ventilation, limits on gatherings (particularly indoors), quarantines, mandates, closure policies and more.

Yet, it may be that only now, in the winter of 2022, when Americans are exhausted with these mitigation methods, that a comparison to the 1918 pandemic is most apt.

The highly contagious omicron variant has rendered vaccines much less effective at preventing infections, thus producing skyrocketing caseloads. And that creates a direct parallel with the fall of 1918, which provides lessons for making January as painless as possible.

In February and March 1918, an infectious flu emerged. It spread from Kansas, through World War I troop and material transports, filling military post hospitals and traveling across the Atlantic and around the world within six months. Cramped quarters and wartime transport and industry generated optimal conditions for the flu to spread, and so, too, did the worldwide nature of commerce and connection. But there was a silver lining: Mortality rates were very low.

In part because of press censorship of anything that might undermine the war effort, many dismissed the flu as a “three-day fever,” perhaps merely a heavy cold, or simply another case of the grippe (an old-fashioned word for the flu).

Downplaying the flu led to high infection rates, which increased the odds of mutations. And in the summer of 1918, a more infectious variant emerged. In August and September, U.S. and British intelligence officers observed outbreaks in Switzerland and northern Europe, writing home with warnings that went largely unheeded.

Unsurprisingly then, this seemingly more infectious, much more deadly variant of H1N1 traveled west across the Atlantic, producing the worst period of the pandemic in October 1918. Nearly 200,000 Americans died that month. After a superspreading Liberty Loan parade at the end of September, Philadelphia became an epicenter of the outbreak. At its peak, nearly 700 Philadelphians died per day.

Once spread had begun, mitigation methods such as closures, distancing, mask-wearing and isolating those infected couldn’t stop it, but they did save many lives and limited suffering by slowing infections and spread. The places that fared best implemented proactive restrictions early; they kept them in place until infections and hospitalizations were way down, then opened up gradually, with preparations to reimpose measures if spread returned or rates elevated, often ignoring the pleas of special interests lobbying hard for a complete reopening.

In places in the United States where officials gave in to public fatigue and lobbying to remove mitigation methods, winter surges struck. Although down from October’s highs, these surges were still usually far worse than those in the cities and regions that held steady.

In Denver, in late November 1918, an “amusement” lobby — businesses and leaders invested in keeping theaters, movie houses, pool halls and other public venues open — successfully pressured the mayor and public health officials to rescind and then revise a closure order. This, in turn, generated what the Rocky Mountain News called “almost indescribable confusion,” followed by widespread public defiance of mask and other public health prescriptions.

In San Francisco, where resistance was generally less successful than in Denver, there was significant buy-in for a second round of masking and public health mandates in early 1919 during a new surge. But opposition created an issue. An Anti-Mask League formed, and public defiance became more pronounced. Eventually anti-maskers and an improving epidemic situation combined to end the “masked” city’s second round of mask and public health mandates.

The takeaway: Fatigue and removing mitigation methods made things worse. Public officials needed to safeguard the public good, even if that meant unpopular moves.

The flu burned through vulnerable populations, but by late winter and early spring 1919, deaths and infections dropped rapidly, shifting toward an endemic moment — the flu would remain present, but less deadly and dangerous.

Overall, nearly 675,000 Americans died during the 1918-19 flu pandemic, the majority during the second wave in the autumn of 1918. That was 1 in roughly 152 Americans (with a case fatality rate of about 2.5 percent). Worldwide estimates differ, but on the order of 50 million probably died in the flu pandemic.

In 2022, we have far greater biomedical and technological capacity enabling us to sequence mutations, understand the physics of aerosolization and develop vaccines at a rapid pace. We also have a far greater public health infrastructure than existed in 1918 and 1919. Even so, it remains incredibly hard to stop infectious diseases, particularly those transmitted by air. This is complicated further because many of those infected with the coronavirus are asymptomatic. And our world is even more interconnected than in 1918.

That is why, given the contagiousness of omicron, the lessons of the past are even more important today than they were a year ago. The new surge threatens to overwhelm our public health infrastructure, which is struggling after almost two years of fighting the pandemic. Hospitals are experiencing staff shortages (like in fall 1918). Testing remains problematic.

And ominously, as in the fall of 1918, Americans fatigued by restrictions and a seemingly endless pandemic are increasingly balking at following the guidance of public health professionals or questioning why their edicts have changed from earlier in the pandemic. They are taking actions that, at the very least, put more vulnerable people and the system as a whole at risk — often egged on by politicians and media figures downplaying the severity of the moment.

Public health officials also may be repeating the mistakes of the past. Conjuring echoes of Denver in late 1918, under pressure to prioritize keeping society open rather than focusing on limiting spread, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention changed its isolation recommendations in late December. The new guidelines halved isolation time and do not require a negative test to reenter work or social gatherings.

Thankfully, we have an enormous advantage over 1918 that offers hope. Whereas efforts to develop a flu vaccine a century ago failed, the coronavirus vaccines developed in 2020 largely prevent severe illness or death from omicron, and the companies and researchers that produced them expect a booster shot tailored to omicron sometime in the winter or spring. So, too, we have antivirals and new treatments that are just becoming available, though in insufficient quantities for now.

Those lifesaving advantages, however, can only help as much as Americans embrace them. Only by getting vaccinated, including with booster shots, can Americans prevent the health-care system from being overwhelmed. But the vaccination rate in the country remains a relatively paltry 62 percent, and only a scant 1 in 5 have received a booster shot. And as in 1918, some of the choice rests with public officials. Though restrictions may not be popular, officials can reimpose them — offering public support where necessary to those for whom compliance would create hardship — and incentivize and mandate vaccines, taking advantage of our greater medical technology.

As the flu waned in 1919, one Portland, Ore., health official reflected that “the biggest thing we have had to fight in the influenza epidemic has been apathy, or perhaps the careless selfishness of the public.”

The same remains true today.

Vaccines, new treatments and century-old mitigation strategies such as masks, distancing and limits on gatherings give us a pathway to prevent the first six weeks of 2022 from being like the fall of 1918. And encouraging news about the severity of omicron provides real optimism that an endemic future — in which the coronavirus remains but poses far less of a threat — is near. The question is whether we get there with a maximum of pain or a minimum. The choice is ours.

On the spectrum from active outbreak to eradication, control is the most likely path forward for COVID-19 in the U.S., NIAID Director Anthony Fauci, MD, said during a National Press Club briefing today.

Fauci’s words served as a reality check for those holding out hope that COVID-19 one day might be as rare as measles or polio in America.

“We’re never going to eradicate this,” he said. “We’ve only eradicated one virus, and that’s smallpox. Elimination may be too aspirational, because we’ve only done that with infections for which we’ve had a massive vaccination campaign like polio and measles. Even though we haven’t eradicated [those viruses] from the planet, we have no cases, with few exceptions, in the U.S.”

Fauci said the country should focus on control — a level of infection “that isn’t zero, but that with the combination of the vast majority of the population vaccinated and boosted, together with those who recovered from infection and also are hopefully boosted, that we will get a level of control that will be non-interfering with our lives, our economy, and the kinds of things we would do, namely to get back to some degree of normality.”

“It’s not going to be eradication, and it’s likely not going to be elimination,” he said again later in the briefing. “It’s going to be a low, low, low level of infection that really doesn’t interfere with our way of life, our economy, our ability to move around in society, our ability to do things in closed indoor spaces.”

Fauci said the only way to achieve this will be with vaccinations, boosters, and mitigation strategies such as wearing masks in congregate settings.

“Over time, we feel confident we will get this under control,” he said. While he said he “hopes” this comes in the “next several months,” he cautioned that he “never predict[s], because you never get it right. Sure enough, someone will come back and say, ‘You said this in December and you were wrong.'”

In terms of boosters, Fauci said it’s possible that a third shot — “and maybe an additional one” — will be enough to provide durable immunity, but that “we’ll just have to wait and see. We don’t know yet.”

Kids under age 5 who have yet to be vaccinated will have to wait a few more months to get their shots, he added. While the lower, 3 μg dose of the Pfizer vaccine looked sufficient for children ages 6 months up to 2 years, that dose was not sufficient for those ages 2 to 5, he said.

“The company decided that they believe this is really a three-dose vaccine, and there’s no doubt if you give three doses you’re going to get an effective and safe vaccine,” he said. “But they haven’t proven it yet, so that’s the delay.”

“I can guarantee you it’s going to be effective,” Fauci added.

Data aren’t expected until the end of the first quarter of 2022, he said, meaning vaccines for this pediatric population likely won’t be available until “a few months into 2022.”

Worldwide deal value from January until mid-November this year hit $5.1 trillion, the highest level since 2015 and a 34% gain compared with all of 2020, KPMG said. U.S. transactions rose to $2.9 trillion, or 55% more than during all of last year.

M&A has soared in 2021 as the economy recovered from a pandemic shock, record monetary and fiscal stimulus pumped up liquidity and many companies sought through acquisitions to regain their footing after months of lockdowns and persistent supply chain disruptions.

A widespread labor shortage will probably push up dealmaking next year. One-third of survey respondents said they want to use M&A to acquire talent, KPMG said.

Also, companies increasingly use acquisitions to change their business or operating models, KPMG said, noting that industrial and financial services companies buy companies that help speed their digital transformation.

“The aim is to increase efficiencies and contribute to having more agile workforces,” according to Carole Streicher, KPMG’s deal advisory and strategy service group leader in the U.S.

Private equity firms will continue to push up the volume and value of M&A next year, after increasing their involvement in transaction value by more than 55% so far in 2021, KPMG said. PE firms have pursued deals this year in part because of the prospect of an increase in corporate capital gains taxes.

Growing support for sustainability among investors, regulators and other stakeholders may prompt M&A, “as businesses look at their ecological footprint and consider purchasing, rationalizing or divesting assets,” KPMG said. Investors are likely to consider sustainable businesses more adaptable to market shifts.

Finally, concerns about the potential for rising borrowing costs may prompt dealmakers who rely on debt financing to speed up acquisition plans. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell late last month said policymakers at their two-day meeting beginning Tuesday will likely consider speeding up the withdrawal of accommodation.

Dealmakers face some headwinds. Democrats in the Senate have yet to muster enough support for a roughly $2 trillion social policy bill that would help sustain economic growth. Meanwhile, the outbreak of the omicron variant of COVID-19 has highlighted the fragility of financial markets and the economy to any setbacks in curbing the pandemic.

Survey respondents identified several factors that will influence dealmaking next year, with 61% underscoring high valuations, 56% pointing to liquidity and other economic considerations, and 55% noting intense competition for a limited number of highly valued acquisition targets, KPMG said.

Still, only 7% of the survey respondents said they expect deal volumes to decline in their industries next year.

Survey respondents work at companies in industries ranging from media and financial services to energy and technology, with 194 of them CFOs, CEOs or other C-suite executives.

The slow return of workers from coronavirus lockdowns has led to labor shortages, competition for hires and an increase in wages.

Employees are switching jobs for higher pay at a near-record pace. The quits rate, or the number of workers who left their jobs as a percent of total employment, rose from 2.3% in January to 2.8% in October, the second-highest level in data going back to 2000, the U.S. Labor Department said. The quits rate hit a high of 3% in September.

Attracting and retaining employees vaulted to the No. 2 ranking of business risks for 2022 and the next decade, from No. 8 a year ago, according to a global survey of 1,453 C-suite executives and board members by Protiviti and NC State University. (Leading the list of risks for 2022 is the impact on business from pandemic-related government policy).

Companies are trying to hold on to workers, and attract hires, by raising pay. Private sector hourly wages rose 4.8% in November compared with 12 months before, according to the Labor Department.

Tight labor markets and the highest inflation in three decades have prompted companies to budget 3.9% wage increases for 2022 — the biggest jump since 2008, according to a survey by The Conference Board.

The proportion of small businesses that raised pay in October hit a 48-year high, with a net 44% increasing compensation and a net 32% planning to do so in the next three months, the National Federation of Independent Business said last month.

CFO respondents to the Deloitte survey said they plan to push up wages/salaries by 5.2%, a nine percentage point increase from their 4.3% forecast during the prior quarter.

“Talent/labor — and several related issues, including attrition, burnout and wage inflation — has become an even greater concern of CFOs this quarter, and the challenges to attract and retain talent could impinge on their organizations’ ability to execute their strategy on schedule,” Deloitte said.

The proportion of CFOs who feel optimistic about their companies’ financial prospects dropped to just under half from 66% over the same time frame.

“CFOs over the last several quarters have become a little more bearish,” Steve Gallucci, managing partner for Deloitte’s CFO program, said in an interview, citing the coronavirus, competition for talent, inflation and disruptions in supply chains.

CFOs have concluded that the pandemic will persist for some time and that they need to “build that organizational muscle to be more nimble, more agile,” he said.

At the same time, CFOs expect their companies’ year-over-year growth will outpace the increase in wages and salaries, estimating revenue and earnings next year will rise 7.8% and 9.6%, respectively, Deloitte said.

“We are seeing in many cases record earnings, record revenue numbers,” Gallucci said.

Describing their plans for capital in 2022, half of CFOs said that they will repurchase shares, 37% say they will take on new debt and 22% plan to “reduce or pay down a significant proportion of their bonds/debt,” Deloitte said.

CFOs view inflation as the most worrisome external risk, followed by supply chain bottlenecks and changes in government regulation, Deloitte said. The Nov. 8-22 survey was concluded before news of the outbreak of the omicron variant of COVID-19.

https://www.cnn.com/2021/12/09/us/hospital-covid-19-deaths-michigan/index.html

Nurse Katie Sefton never thought Covid-19 could get this bad — and certainly not this late in the pandemic. “I was really hoping that we’d (all) get vaccinated and things would be back to normal,” said Sefton, an assistant manager at Sparrow Hospital in Lansing, Michigan. But this week Michigan had more patients hospitalized for Covid-19 than ever before. Covid-19 hospitalizations jumped 88% in the past month, according to the Michigan Health & Hospital Association.

“We have more patients than we’ve ever had at any point, and we’re seeing more people die at a rate we’ve never seen die before,” said Jim Dover, president and CEO of Sparrow Health System.

“Since January, we’ve had about 289 deaths; 75% are unvaccinated people,” Dover said. “And the very few (vaccinated people) who passed away all were more than 6 months out from their shot. So we’ve not had a single person who has had a booster shot die from Covid.”

Among the new Covid-19 victims, Sefton said she’s noticed a disturbing trend.

“We’re seeing a lot of younger people. And I think that is a bit challenging,” said Sefton, a 20-year nursing veteran.She recalls helping the family of a young adult say goodbye to their loved one. “It was an awful night,” she said. “That was one of the days I went home and just cried.”

It’s not just Michigan that’s facing an arduous winter with Covid-19. Nationwide, Covid-19 hospitalizations have increased 40% compared to a month ago, according to data from the US Department of Health and Human Services. This is the first holiday season with the relentless spread of the Delta variant — a strain far more contagious than those Americans faced last winter.

“We keep talking about how we haven’t peaked yet,” Sefton said.Health experts say the best protection against Delta is to get vaccinated and boosted. But as of Thursday, only about 64.3% of eligible Americans had been fully vaccinated, and less than a third of those eligible for boosters have gotten one.

Sparrow Hospital nurse Danielle Williams said the vast majority of her Covid-19 patients are not vaccinated — and had no idea they could get pummeled so hard by Covid-19.“Before they walked in the door, they had a normal life. They were healthy people. They were out celebrating Thanksgiving,” Williams said. “And now they’re here, with a mask on their face, teary eyed, staring at me, asking me if they’re going to live or not.”

Dover said he’s saddened but not surprised that his state is getting walloped with Covid-19.“Michigan is not one of the highest vaccination states in the nation. So it continues to have variant after variant grow and expand across the state,” he said.

“The next few weeks look hard. We’re over 100% capacity right now,” Dover said.”Most hospitals and health systems in the state of Michigan have gone to code-red triage, which means they won’t accept transfers. And as we go into the holidays, if the current growth rate that we’re at today, we would expect to see 200 in-patient Covid patients by the end of the month — on a daily basis.”And that would mean “absolutely stretching us to the breaking point,” Dover said.”We’ve already discontinued in-patient elective surgeries,” he said. “In order to create capacity, we took our post-anesthesia recovery care unit and converted it into another critical care unit.”

Nurse Leah Rasch is exhausted. She’s worked with Covid-19 patients since the beginning of the pandemic and was stunned to see so many people still unvaccinated enter the Covid unit.

“I did not think we’d be here. I truly thought that people would be vaccinated,” the Sparrow Hospital nurse said.”I don’t remember the last time we did not have a full Covid floor.”The relentless onslaught of Covid-19 patients has impacted Rasch’s own health. “There’s a lot of frustration,” she said. “The other day, I had my first panic attack … I drove to work and I couldn’t get out of the car.”

Dover said many people have asked how they can support health care workers.”If you really want to support your staff, and you really want to support health care heroes, get vaccinated,” he said. “It’s not political. We need everybody to get vaccinated.”

He’s also urging those who previously had Covid-19 to get vaccinated, as some people can get reinfected.”My daughter’s a good example. She had Covid twice before she was eligible for a vaccine,” Dover said. “She still got a vaccine because we know that if you don’t get the vaccine, just merely having contracted Covid is not enough to protect you from getting it again. And I know that from personal experience. “And those who are unvaccinated shouldn’t underestimate the pandemic right now, Dover said.

“The problem is, it’s not over yet. I don’t know if people realize just how critical it still is,” he said.”But they do realize it when they come into the ER, and they have to wait three days for a bed. And at that point, they realize it.”

Americans seem to be greeting the Omicron variant with a collective “eh,” according to new polling data from Axios/Ipsos.

Compared to other COVID-19 strains, Omicron seems to be extra transmissible and possibly more likely to cause breakthrough infections, at least based on preliminary data. As of Dec. 8, 22 U.S. states had reported at least one case related to the variant. But despite the early panic about the variant, most people surveyed by Axios/Ipsos in early December said they weren’t going to make big changes to their behavior. Specifically, the poll found that just:

It’s hard to blame people. At this point in the pandemic, it’s safe to say everyone is tired and ready to be done with COVID-19. Plus, 60% of the U.S. population is now fully vaccinated, and thus, based on what we’ve seen so far, largely protected from the worst the virus can do. People who have received a booster dose are in an even better position, given early reports that boosters hold up well against Omicron.

Americans are also, to some degree, doing what public figures told them to do. President Joe Biden called Omicron “a cause for concern—but not a cause for panic.” And many health officials have jumped to assure the public that we are not going back to square one, thanks to the protection offered by vaccines.

The caveat, however, is that we’re still learning about Omicron. Early indications suggest the variant does not cause more severe disease than other variants, but it’s too soon to say that definitively. If it does turn out to be highly contagious, good at outsmarting vaccines and capable of causing serious disease, we may have to return to some precautions, for the sake of individuals and our overburdened health care system. The variant is already taking root in Europe, which may be a harbinger of what’s to come here.

The good news? The Axios/Ipsos poll did find that most Americans are still willing to step up and take protective measures when necessary. More than 60% said they were likely to go back to (or continue) always masking in public, and almost 70% said they’d support businesses requiring customers to wear masks.